Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most frequent valvular heart disease in the Western world. During decades with slow progression of severity, the prognosis is good as long as the patient is asymptomatic. However, this changes dramatically with the onset of symptoms, which reduce the expected survival to a few years. All trials on various medical therapies have failed to demonstrate any efficacy in delaying disease progression, and the dismal fate of patients with severe symptomatic AS can only be reversed by aortic valve replacement (AVR). Despite this, a European survey in 2001 revealed that one third of patients with symptomatic severe AS were denied surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) due to advanced age, other comorbidities, and frailty1.

In 2002, the first successful transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was performed. This was the first step in a paradigm shift introducing TAVI as an important alternative to SAVR. The initial patient cohort addressed with TAVI was ineligible for SAVR. The PARTNER 1B trial randomised 358 patients with symptomatic severe AS and extreme surgical risk to either TAVI or medical treatment including balloon aortic valvulotomy2. Patients were deemed not suitable for SAVR as their predicted probability of death or other serious irreversible condition within 30 days was above 50%, according to the agreement of a multidisciplinary Heart Team including at least two cardiac surgeons. The trial provided evidence that TAVI improved both the prognosis and symptoms of the patients. Today, the role of the Heart Team in patients ineligible for SAVR is to discuss whether TAVI should be recommended or whether this intervention is futile.

Later, several randomised clinical trials compared TAVI and SAVR in patients with high, intermediate, and recently low surgical risk3,4,5. Primary endpoints have been safety measured at one or two years, which has consistently shown that TAVI is at least non-inferior to SAVR. However, due to the different nature of transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement, other outcomes have favoured either TAVI or SAVR. Thus, in general TAVI provides a larger effective orifice area, and lower transvalvular pressure gradient, bleeding, acute kidney injury, and new-onset atrial fibrillation. On the other hand, SAVR is associated with a lower rate of paravalvular leakage, vascular complications, and conduction abnormalities.

Another important issue which needs to be taken into consideration in the interpretation of the evidence for TAVI versus SAVR is that most randomised clinical trials only included highly selected patients, who were good candidates for TAVI. Thus, in the PARTNER 3 and Evolut Low Risk trials4,5, patients with iliofemoral arteries not suitable for safe access, coronary arteries with low take-off, severe aortic valve calcification, and left ventricle outflow tract calcification were excluded. Therefore, it can be questioned whether the findings of these trials are applicable to all-comer patients with severe symptomatic AS and low surgical risk.

Furthermore, the patients studied have been elderly with a mean age of 75-80 years, which is in contrast to current surgical practice, where bioprosthetic aortic valves are used in even younger patients in order to avoid anticoagulation therapy – and probably also with the expectation that a failed surgical bioprosthetic aortic valve can be handled with TAVI. However, bicuspid aortic valves are more common in these younger patients, and it is important to keep in mind that bicuspid aortic valves have been excluded from all randomised trials comparing TAVI and SAVR.

Another issue when treating patients with longer life expectancy is the durability of bioprosthetic aortic valves. Although a recent study has reported similar outcomes after TAVI and SAVR after six years6, longer follow-up is needed before the durability of transcatheter heart valves can be established. When the transcatheter heart valve (THV) fails, TAVI-in-TAVI has been suggested as a solution although this may potentially lead to difficulties in accessing the coronary arteries7.

In 2012, the ESC guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease introduced the term “Heart Team”, intended as a multidisciplinary team that had to assess the surgical risk of the patient and refer the inoperable patient to TAVI when the eligibility criteria were fulfilled8. The role of the Heart Team was confirmed in 2017 with the recommended requirements of a Heart Valve Centre9, as centres of excellence in the treatment of valvular heart diseases and delivery of better quality of care. Part of this is that the Heart Team meets on a regular basis and works with standard operating procedures.

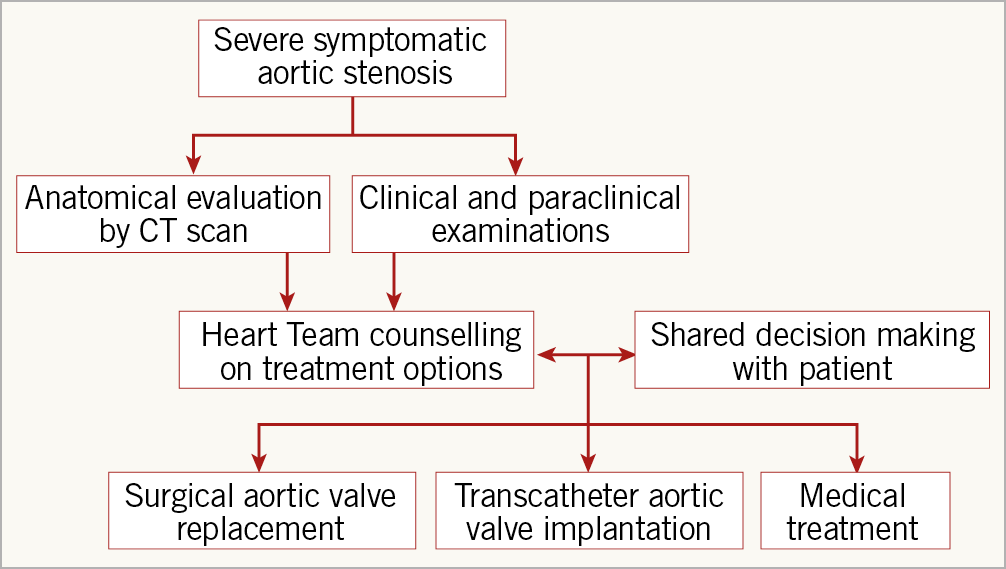

Whereas the role of the Heart Team at the start of the TAVI era was relatively simple, i.e., determining that the patient was ineligible for SAVR and that TAVI was not futile, the decision making is now becoming much more complex when addressing patients with longer life expectancy. Ideally, the Heart Team should base its counselling on anatomical features related to SAVR and TAVI, comorbidities, frailty, as well as patient preference. This may require a new pathway (the “Heart Team 2.0”) for patients with severe symptomatic AS, who are referred for AVR (Figure 1). Thus, all patients should undergo the same work-up before the Heart Team discussion. This involves computed tomography (CT) scanning, which is crucial in the evaluation of anatomical features such as access routes for TAVI (transfemoral approach possible?), calcification of the ascending aorta (porcelain?), aortic valve morphology (bicuspid or tricuspid?), degree of calcification of the aortic valve complex, aortic valve diameter (risk of patient-prosthesis mismatch?), height of take-off of the coronary arteries, etc. Similarly, various comorbidities may favour either SAVR or TAVI. Thus, detailed clinical and paraclinical evaluations must be available for the Heart Team. This information should not only be used to decide the strategy for AVR, but also take into consideration the consequences of re-valving when the bioprosthetic valve fails.

Figure 1. The “Heart Team 2.0” flow chart.

Shared decision making, where the Heart Team and patient work together, puts people at the centre of decisions about their own treatment and care. During shared decision making, it is important that care or treatment options are fully explored, along with their risks and benefits, different choices available to the patient are discussed and a decision is reached together. Expansion of TAVI to patients with severe symptomatic AS, who are not only at lower surgical risk but also have longer life expectancy, calls for a reinforcement of the Heart Team. The foundation for this includes a more detailed work-up of all patients referred for AVR in order to counsel on both short- and long-term advantages and disadvantages related to SAVR and TAVI; shared decision making is mandatory to put the patient at the centre of the decision.

Conflict of interest statement

L. Søndergaard has been a consultant for and received institutional research grants from Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific and Edwards Lifesciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.