Abstract

Aims: Little is known about how “Heart Team” treatment decisions among patients suitable for either surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) are made under routine conditions.

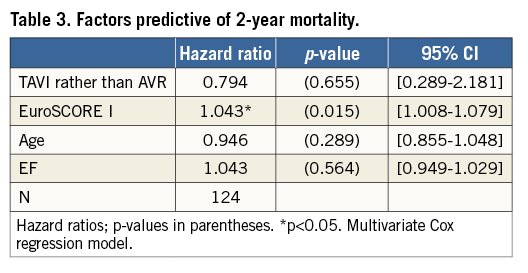

Methods and results: The “Heart Team” decision-making process was analysed with respect to124 patients of a non-randomised prospective clinical trial that included patients aged ≥75 years: 41 patients underwent AVR and 83 underwent TAVI. By use of the non-parametric classification and regression tree (CART) methodology, 21 baseline parameters were tested to reconstruct the decision process retrospectively. Next, multivariate logistic and Cox regression models were fitted to evaluate the decision and outcome relevance (two-year survival) of the parameters as identified in the CART procedure. For patients with a baseline EuroSCORE I ≥13.48%, no further cut-off points were identified and the majority of these patients underwent TAVI. Among patients with a baseline EuroSCORE I <13.48%, age and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were identified as further relevant decision parameters. The decision relevance of EuroSCORE I (p=0.003), age (p=0.024) and LVEF (p=0.047) were confirmed by multivariate analysis; however, outcome relevance can be confirmed for EuroSCORE I (p=0.015) only, while treatment decision (TAVI or AVR) was not a significant predictor of mortality (p=0.655).

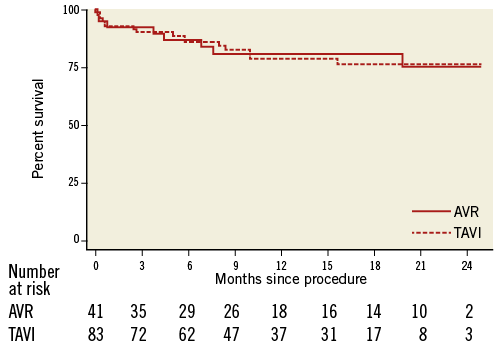

Conclusions: Despite or even because of the systematic risk selection according to EuroSCORE I values, we observed two-year survival rates of about 75% regardless of whether the patient received TAVI or AVR, suggesting that the decisions made by the “Heart Team” were appropriate. German Clinical Trial Register Nr. DRKS00000797

Introduction

The decision as to choice of treatment for elderly patients with symptomatic aortic valve stenosis (AS) remains controversial1,2. The increasing life expectancy observed in most western countries such as Germany has led to a rising prevalence of patients presenting with AS and has even complicated the decision process, as ageing is associated with an increase in comorbidities, and consequent higher postoperative morbidity and mortality3. The gold standard in the treatment of aortic valve stenosis has long been surgical intervention by aortic valve replacement (AVR) or valve repair4,5. Since the first-in-man implants in 2002, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become established as a new standard of care for inoperable patients6. Hence, clinical complications and long-term outcomes of TAVI are the subject of extensive clinical research7-9.

According to the ESC/EACTS Guidelines10, TAVI is recommended for patients considered unsuitable for conventional surgery because of severe comorbidities. In patients considered to be at high risk for conventional surgery, these comorbidities and the associated individual patient’s risk should be assessed by a “Heart Team” of cardiac surgeons and cardiologists to select the optimal treatment strategy for individual patients10. Unfortunately, little evidence is available for validation and evaluation of the “Heart Team” approach11,12.

In the present study we sought to analyse how treatment decisions are made in AS patients suitable for AVR or TAVI by a “Heart Team” approach and which patient-specific baseline parameters influence the decision-making process.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

The patient population in this analysis consisted of 124 patients with severe aortic stenosis who were enrolled in the non-randomised prospective “TAVI Calculation of Costs Trial” (TCCT) and treated under routine clinical conditions by either AVR or TAVI. According to the study protocol, only patients aged ≥75 years were included. Treatment decisions were made by a study-independent “Heart Team” of cardiac surgeons and cardiologists according to best clinical practice. Finally, 41 patients underwent AVR and 83 underwent TAVI. Outpatient visits were scheduled at three, six, 12, 18 and 24 months with additional monthly telephone follow-up in-between.

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Quantitative continuous variables are described with means±standard deviation and quantitative discrete variables with relative frequencies. Differences between treatment groups were analysed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. The distribution of patients according to treatment option by the interdisciplinary colloquium is assumed to: 1) be mainly influenced by patient presentation, characterised by a number of baseline parameters; and 2) lead to systematic differences between the treatment groups. In order to understand this properly, the “Heart Team” decision-making process was analysed using the non-parametric classification and regression tree (CART) analysis. CART is an example of so-called machine learning methods and has been modified over the years in various directions. We applied a CART procedure as suggested by Schumacher et al13. Briefly, the applied CART programme first determines a cut-off point for each possible predictor variable by which the population could be split into two subgroups (lowest p-value of a logistic regression) which best explains the binary endpoint of the analysis (TAVI or AVR) and then selects the predictor with the lowest p-value to determine a first split. The process is then repeated on the resulting subgroups until no further partitioning is warranted (no cut-off at a p-value <0.05 possible) or the resulting subgroup is considered too small (subgroup smaller than

![]()

which results in a minimal size of 12). The final result is a decision tree.

In the present study, a total of 21 patient-specific baseline parameters, such as risk scores, pre-existing conditions or self-reported quality of life values (Table 1), were used to reconstruct retrospectively the decision process leading to the final treatment choice. Next, a multivariate logistic regression model was fitted to confirm the decision-relevant parameters as identified in the CART procedure. Finally, two-year cumulative survival rates were estimated by means of the Kaplan-Meier method14, and the confirmed decision-relevant parameters were included as covariates in a Cox regression model15. Theoretically, an analysis of the treatment effect (TAVI or AVR) including all decision-relevant parameters as covariates may lead to an unbiased estimation of the treatment effect, assuming that all factors influencing both the choice and the prognosis are accounted for16. With the typical limitations of a limited sample size and unobservable variables, this is unrealistic. However, taking the most important factors in the decision process into account can be a first step to approaching a more realistic effect. Furthermore, it allows checking whether the factors identified as most important for the decision process are actually of prognostic value. The proportional hazards assumption was verified by Stata’s PH-assumption test using Schoenfeld residuals.

For missing variables, multiple imputation was applied except for the CART procedure, where a second data set was generated with the application of conditional mean imputation. All analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

PATIENT POPULATION

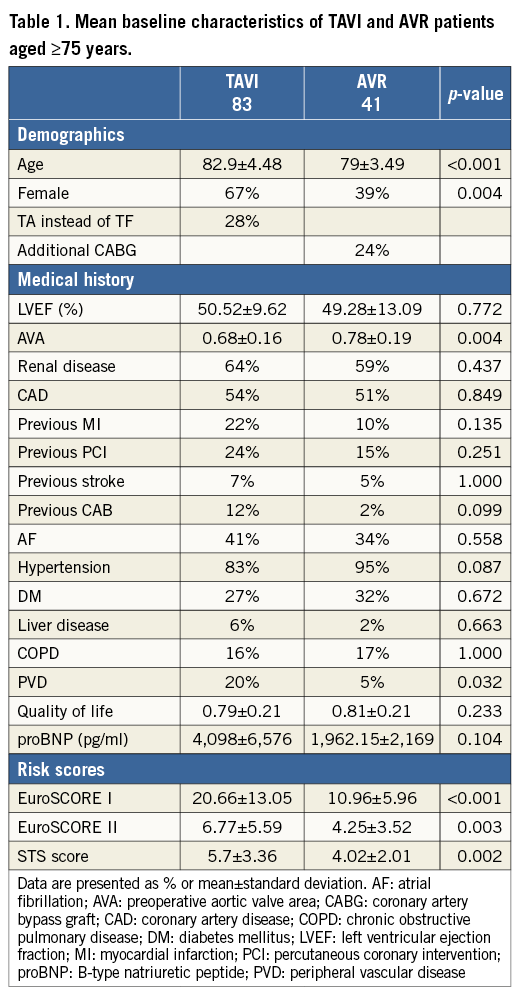

Baseline demographics and characteristics are given in Table 1. According to the “Heart Team” decision, 41 and 83 patients underwent AVR and TAVI, respectively. AVR patients were younger (p<0.001) with lower EuroSCORE I (p<0.001) and EuroSCORE II values (p=0.003) as well as lower STS scores (p=0.002) than patients in the TAVI group. There was also a gender imbalance, with a higher proportion of females undergoing TAVI (p=0.004). TAVI patients more often had a medical history of peripheral vascular disease (p=0.032).

CLINICAL DECISION MAKING AND TREATMENT CHOICES

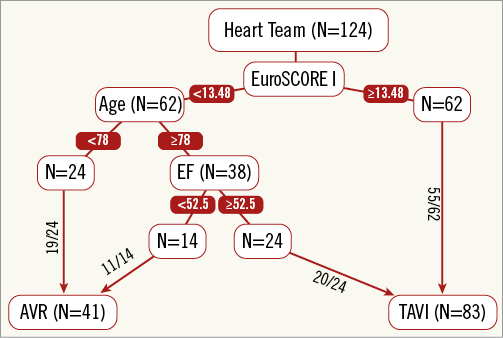

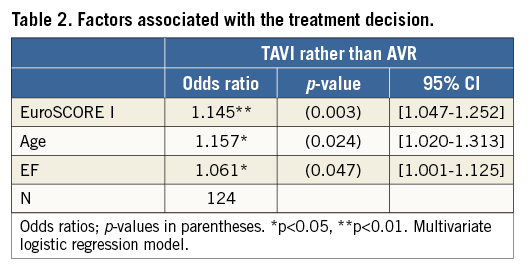

To identify decision-relevant factors among the baseline characteristics, all of the available 21 patient-specific baseline characteristics were included in the CART procedure. The results of the analysis are shown in Figure 1. For the major decision between AVR and TAVI, the EuroSCORE I was identified as the strongest predictor with a cut-off value of 13.48% (p<0.001) whereas the STS score and EuroSCORE II were of only minor relevance. Among patients with a baseline EuroSCORE I less than 13.48%, age and ejection fraction (EF) were identified as further decision-relevant parameters. Among patients with a baseline EuroSCORE I greater than 13.48%, no further cut-off points were identified, and the majority of these patients underwent TAVI.

Figure 1. Treatment decision for patients aged ≥75 years. Decision tree according to the CART procedure.

As shown in Table 1, patients selected for the TAVI procedure were, on average, of higher age, and showed smaller aortic valve areas and higher EuroSCORE I. However, between-group differences in the mean ejection fraction were negligible. Analogously, the multivariate logistic regression model with the decision-relevant parameters as identified in the CART procedure confirmed that patients with an increased risk of mortality predicted by EuroSCORE I, of greater age, and/or with preserved ejection fraction were more likely to undergo TAVI than AVR (Table 2).

TWO-YEAR SURVIVAL

Periprocedural survival (within 72 hours) was 100% and 99% for patients who underwent AVR and TAVI, respectively. Two-year Kaplan-Meier curves of patients who received TAVI or AVR are shown in Figure 2. For both therapies, two-year survival rates were 75% without any significant differences (HR=1.03; p=0.94).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of TAVI and AVR patients aged ≥75 years.

According to the multivariate analysis, EuroSCORE I was identified as an independent predictor of mortality (Table 3), while treatment decision (TAVI or AVR) was still not a significant predictor of mortality (p=0.66).

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that treatment decisions made by “Heart Teams” appear to be mainly influenced by well-accepted risk factors and result in two-year survival rates of 75% for both AVR and TAVI patients. These results are not only comparable with recent results for AVR and TAVI patients who were selected by a “Heart Team” under routine conditions17,18, but also show that, despite the systematic risk selection, there are comparable survival rates regardless of whether the patient underwent TAVI or AVR.

In the changing clinical environment that has followed the introduction of TAVI, empirically derived real-world data are of the utmost importance. In this elderly, rather heterogenous patient population, decision making is particularly complex given the wide range of perioperative risk factors and life expectancy due to the individual cardiac and non-cardiac patient characteristics. Generally, it is assumed that the “Heart Team” approach may have additional value for tailored decision making10,11,19-22. This has been discussed to extend the concept further23.

Complementary to randomised controlled trials, a prospective study such as the TAVI Calculation of Costs Trial is well suited to capture all decision-relevant information within real-world clinical practice for evaluation of the “Heart Team” concept11. Although the observed two-year survival rates of 75% following the “Heart Team” decision-based treatment look promising, we usually have no insights into the complex decision process and the comorbidity conditions of relevance17,18,24,25. In the present analysis, we demonstrated that the decision is mainly influenced by well-known risk factors. Moreover, at least one of these factors, the EuroSCORE I, was an independent predictor of survival in this population. Further, we observed for both therapeutic options that survival times were comparable with previous results17,18, indicating no substantial harm by using the “Heart Team” approach.

Almost one decade ago, Iung and colleagues carried out an analysis very similar to ours, identifying the decision-relevant factors among patients with severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis, aged ≥75, but with respect to the treatment options AVR and drug therapy only5. Interestingly, their findings were quite similar to ours: decision-relevant factors were left ventricular ejection fraction, age and the Charlson comorbidity score, which was favoured over the EuroSCORE because the latter includes variables related to the timing and modalities of surgery, making the EuroSCORE inappropriate for a comparison between operated and non-operated patients.

The patient population analysed by Iung and colleagues was of similar age to ours, but had a substantially lower risk of mortality predicted by EuroSCORE I (Iung: 8.1 for patients operated and 9.4 for patients denied surgery). Moreover, Iung and colleagues identified left ventricular (LV) dysfunction as a driving factor for the decision not to operate5. In contrast, in the present analysis, patients with good LV function were more likely to be distributed to the TAVI group.

Finally, one of the main conclusions in this highly recognised article was the following: “These findings underline particular difficulties regarding decision-making in the elderly, in whom current guidelines provide limited recommendations as a consequence of the low level of evidence from the literature. Randomised trials are unlikely to be conducted in this field, thus further prospective studies including quantification of comorbidities are necessary to enable risk-benefit ratio to be better evaluated and, therefore, guidelines to be refined”5.

Although decisions are nowadays more focused on AVR and TAVI procedures, we believe that this main conclusion remains valid and topical. Guidelines still provide rather limited recommendations as a consequence of the low level of evidence from the literature and the astonishing speed of medical progress in this specific field10. Today, however, this lack of evidence seems to be bypassed by the magic bullet of a “Heart Team” of cardiac surgeons and cardiologists to select the optimal treatment strategy for individual patients11,12. Accordingly, we believe that both analysis and routine comparison of treatment decisions made by “Heart Teams” are of major importance for evaluation of this concept. The methodology applied should be replicated in other centres in order to guarantee a high level of transparency and to optimise treatment decision making further.

Of course, the participants in the “Heart Team” may have had additional (not documentable) information as they had the possibility to visit the patient personally. The aim behind the applied decision analysis, however, was to fade out any additional information and to reconstruct the decision process by means of the patient-specific baseline parameters only in order to give an insight into which documented parameter has an impact on the treatment decision. In addition, organisational factors such as the department of admission may have influenced the treatment decision.

In conclusion, in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis a presumed increased risk of perioperative mortality as predicted by EuroSCORE I is the major independent determinant in the clinical decision-making process in a “Heart Team” approach, while patient age and ejection fraction can be considered as secondary factors. Despite or even because of this systematic risk selection, we observed two-year survival rates of about 75% regardless of whether the patient underwent TAVI or AVR, suggesting that the decisions made by the “Heart Team” were appropriate.

| Impact on daily practice Little is known about how “Heart Team” treatment decisions among patients suitable for either surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) are made under routine conditions. In our centre, the logistic EuroSCORE I was identified as the strongest predictor with a cut-off value of 13.48%. In addition, we observed two-year survival rates of about 75% regardless of whether the patient underwent TAVI or AVR, suggesting that the decisions made by the “Heart Team” were appropriate. |

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to staff members Melanie Avlar, Jutta Schmitz and Christiane Rack for data collection, and thank Gordon Goodall (Edwards Lifesciences) for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

The TCCT study was funded by Edwards Lifesciences. However, no restrictions were placed on either the design or the presentation of results, or the interpretation of data.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.