The oral P2Y12 inhibitors prasugrel and ticagrelor are recommended in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); however, they are associated with high residual platelet reactivity (HRPR) up to 4-6 hours after loading1. On-treatment HRPR correlates with procedural success, myocardial damage and clinical outcomes. Hence, more rapid antiplatelet agents remain desirable in STEMI. Cangrelor is an intravenous (IV) P2Y12 inhibitor with a rapid and reversible antiplatelet effect, though it prompts a lower inhibition of platelet aggregation (IPA) at light transmittance aggregometry (LTA) than tirofiban, an intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI)2. Moreover, cangrelor is licensed for use at the time of PCI, whereas the upstream administration of potent antiplatelets could more efficiently block thrombus formation and propagation, which is highly platelet-dependent in the early phase of coronary thrombogenesis.

RUC-4 is a novel class of second-generation GPI which has shown a good safety profile and high IPA (measured by LTA) within 15 minutes in aspirin-treated patients with chronic coronary syndrome3. Thus far, no pharmacodynamic (PD) or pharmacokinetic (PK) assessment of RUC-4 has been reported in STEMI patients.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Bor et al report the results of an open-label study investigating the PD/PK effect and tolerability of subcutaneous RUC-4 injection in 27 STEMI patients4.

Three RUC-4 doses were tested – 0.075 mg/kg, 0.090 mg/kg and 0.110 mg/kg. The primary endpoint was IPA ≥77% measured by VerifyNow P2Y12 assay with the thrombin receptor activating peptide channel at 15 minutes. The study found that a dose response of RUC-4 on IPA (mean inhibition of 77.5%, 87.5% and 91.7% from the lowest to the highest dose; ptrend=0.002) and ≥50% inhibition was retained after 89.1, 104.2, and 112.4 minutes in the three cohorts, respectively. RUC-4 was safe and well tolerated (mild access-site haematomas occurred in 22% of patients and severe access-site haematomas in 7% of patients), with no cases of thrombocytopaenia. These study findings, and how they could pave the way forward, trigger several considerations.

In this study, RUC-4 was administered in the catheterisation laboratory. However, RUC-4 is being developed as an in-ambulance treatment (NCT04825743). The authors emphasise that RUC-4 eliminates the need for IV administration as a bolus and infusion controlled by a pump compared with GPI, with a quick offset of action. However, GPIs have been investigated as bolus-only administration, providing similarly potent, rapid and transient IPA1. Moreover, establishing and maintaining an IV line is the current standard of care in the ambulance setting, irrespective of the need to administer antithrombotic medications. Therefore, one wonders whether the subcutaneous route truly offers meaningful advantages compared with the IV administration in this setting.

The comparative frequency of thrombocytopaenia between GPIs (particularly the small molecules) and RUC-4, which has potential to limit this occurrence, requires further investigation, especially considering that tirofiban was associated with three self-limiting cases of thrombocytopaenia out of 372 (0.8%) patients in the MULTISTRATEGY trial5.

Intravenous GPIs have been tested (and ultimately abandoned) in the pre-hospital setting, largely because of the bleeding risk. Whether the use of the radial access and a more transient IPA with new parenteral platelet inhibitors provides net benefit remains to be determined.

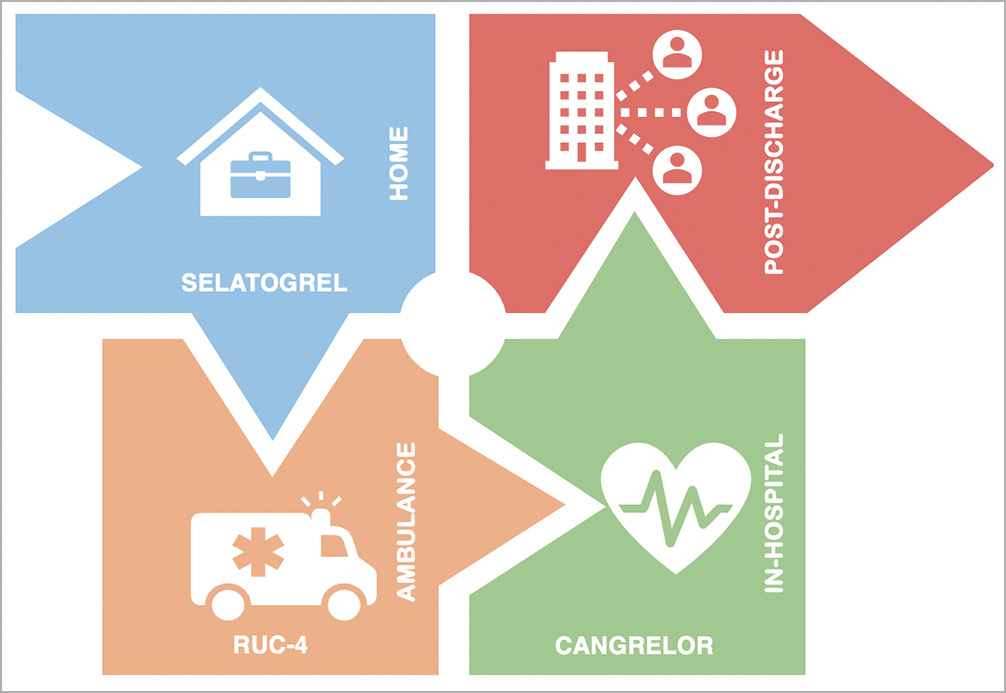

Selatogrel, a new parenteral subcutaneous P2Y12 inhibitor, has also been developed for this purpose6. Yet, unlike RUC-4, this treatment is meant to be self-administered by the patient at the time of symptom onset, which offers obvious advantages in terms of treatment delay but may carry the risks associated with self-administration. The optimal timing of pre-hospital treatment administration (self-administration versus ambulance) and the most effective pathway for inhibiting platelet activation and aggregation (αIIbβ3 versus P2Y12 antagonists) remain unclear. Meanwhile, pre-treatment with oral P2Y12 inhibitors is being discouraged, and a new era of studies investigating parenteral antiplatelet therapies in the pre-hospital setting is on the horizon (Figure 1). This will provide an opportunity to assess whether pre-hospital parenteral antiplatelet agents have been dismissed too quickly in the past and whether the recent advances in preventing and treating access-site bleeding risks will suffice for them to stay.

Figure 1. Timing of parenteral antiplatelet agent administration in the management of STEMI.

Conflict of interest statement

M. Valgimigli reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Alvimedica/CID, Abbott Vascular, Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer, CoreFlow, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Universität Basel/Dept. Klinische Forschung, Vifor, Bristol Myers Squibb SA, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Vesalio, Novartis, Chiesi, and PhaseBio, and grants and personal fees from Terumo, outside the submitted work. A. Landi has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.