Abstract

Aims: Myocardial infarction is a medical emergency in which 25 to 35% of patients will die before receiving medical attention. The Stent for Life registry was launched to access the current situation of the Egyptian population presenting with STEMI, and to determine what were the barriers to providing patients with cardiac problems appropriate care.

Methods and results: This registry was conducted at 14 centres covered all the Egyptian regions including 1,324 consecutive patients presenting with STEMI during the period between January 1st, 2011 to November, 2011. Fourteen centres and 38 interventionalists participated in this registry; only six centres are Pilot Centres (fulfilling the criteria for a primary PCI centre) and were assigned at the end of 2011. Cardiovascular risk factors were mainly smoking (60.5%), dyslipidaemia (46.0%), diabetes (51.4%) and hypertension (56.0%). The mean age at presentation was 56.01±10.61years and 75.0% were male. Only 5% of the STEMI patients arrived via the emergency medical system. Thrombus aspiration was done in 42.7% of patients in primary PCI group and 25.9% in rescue PCI group. Bare metal stents (BMS) were used in 80.7% of the stented patients while drug eluting stents (DES) were used in 19.3% of the stented patients. In-hospital mortality was 2.9% (1.4% in primary PCI group, 1.1% in patients treated with thrombolysis and 0.4% in patients receiving no reperfusion therapy).

Conclusion: Despite the logistical difficulties, excellent outcomes for acute interventional reperfusion strategy in STEMI can be achieved in our country, possibly similar to those seen in the West. There is a strong need for making the practice of PCI in STEMI more widespread in developing regions.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction is a medical emergency which demands both immediate attention and activation of the emergency medical services because it is the leading cause of death for both men and women all over the world1. Of all patients experiencing a myocardial infarction, 25 to 35% will die before receiving medical attention2. The ultimate goal of management in the acute phase of the disease is to salvage as much myocardium as possible and prevent further complications, either with thrombolytic therapy or primary PCI. As time passes, the risk of damage to the heart muscle increases; hence the phrase that in myocardial infarction, “time is muscle” and “time wasted is muscle lost”3.

Thrombolytic therapy to abort a myocardial infarction is not always effective. The degree of effectiveness of a thrombolytic agents is dependent on the time when the myocardial infarction began, with the best results occurring if the thrombolytic agent is used within two hours of the onset of symptoms4. Failure rates of thrombolytic therapy can be as high as 20% to 40% or higher5.

Reperfusion of the infarct artery can also be achieved by a catheter-based strategy. When PCI is used in lieu of fibrinolytic therapy within 12 hours of onset of STEMI, it is referred to as primary PCI. When fibrinolysis has failed to reperfuse the infarct vessel or a severe stenosis is present in the infarct vessel, a rescue PCI can be performed, 12 hours after failed fibrinolysis, to salvage as much myocardium as possible and prevent further complications. An approach of ischaemia-driven PCI can be used to manage STEMI patients only when spontaneous or exercise-provoked ischaemia occurs, whether or not they have received a previous course of fibrinolytic therapy. Post-thrombolytic PCI is reasonable in patients with STEMI and a patent infarct artery three to 24 hours after fibrinolytic therapy6.

Patients with STEMI presenting to a hospital without PCI capability should be transferred for primary PCI within 120 minutes of first medical contact and, if this is not possible and fibrinolytic therapy was given as primary reperfusion therapy, patients should be transferred to a PCI-capable facility as soon as possible where PCI can be performed when needed7.

Data collected from ACESS registry8 concluded that, in Egypt, acute coronary syndromes (ACS) occur at a younger age, treatment of ACS follows the international practice guidelines, but mainly conservative and reperfusion therapies are not implemented in about 60% of cases. Egypt is currently contributing to the European project of Stent for Life (SFL) as one of 10 targets countries in the next few years with many pilot centres9.

Through this project, obstacles facing the implementation of adequate therapy were pointed and plans were formed to solve them and thus reduce further the risk of long-term ischaemic events in ACS patients in EGYPT.

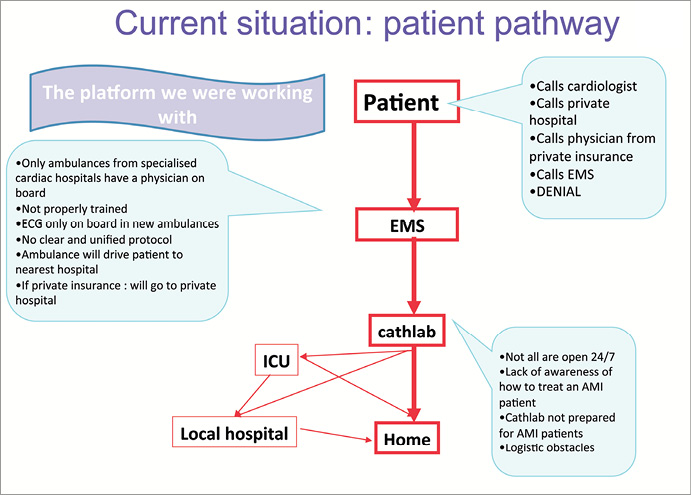

Some of these obstacles include: traffic delay; crowded streets; delayed emergency response; patients who do not have any knowledge about the risk factors and symptoms; also inadequate knowledge on the part of the paramedic teams to identify whether the symptoms are STEMI or not; low grade paramedics and emergency equipment; emergency room physicians who cannot identify or characterise the symptoms in such a way as to determine clearly whether this is a STEMI, and thus being unable to decide whether an urgent operation is called for or whether the case can wait; also the demonstrated need on the part of junior cardiologists to be aware of interventional guidelines and updates and to be trained, as well, in implementing them (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the current Egyptian organisation.

SFL implementation

A series of consecutive meetings were held to discuss how to implement solutions for these various difficulties that faced the project. The following activities were held:

1st SFL forum

The first SFL forum took place with the Egyptian application of the European Practice Guidelines, at the Palestine Hotel on the 8th of December 2011, held under the supervision of Egyptian Society of Cardiology in collaboration with the European committee of Practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Targets projects of the Egyptian Stent for Life committee.

Press conference

A press conference was held at the CARDIO EGYPT conference in Sharm El Sheikh. This meeting was very important for the initiative as it included various TV channels, the leading Egyptian newspapers along with the Stent for Life committee. The lively discussions helped to clarify our aim and plans.

Stent for Life’s first Egyptian patient awareness campaign was launched at the Alexandria Sporting Club on the 23rd December 2011 before a crowd of around 200 attendees representing a wide variety in ages, sex and needs.

It began with a check-up for the attendees including:

– Blood sugar tests

– Blood pressure tests

– Cholesterol percentage tests

– The Framingham study risk scores

A seminar was held by Egyptian cardiologists led by Mohammed Sobhy with audience interaction and questions that were answered by the Board. Flyers with basic instructions on how to protect your heart from any health crisis were distributed.

1st Satellite: Professors meet Junior physicians education meeting

The meeting was held Sunday the 22nd of January 2012 at the National Heart Institute Egypt. The Stent For Life Board and the elites in cardiology from all over the country shared the latest updates with the cardiologists in the NHI.

Completing the 1st phase of the registry

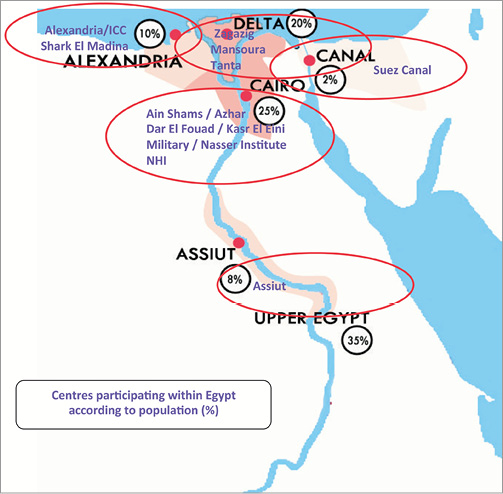

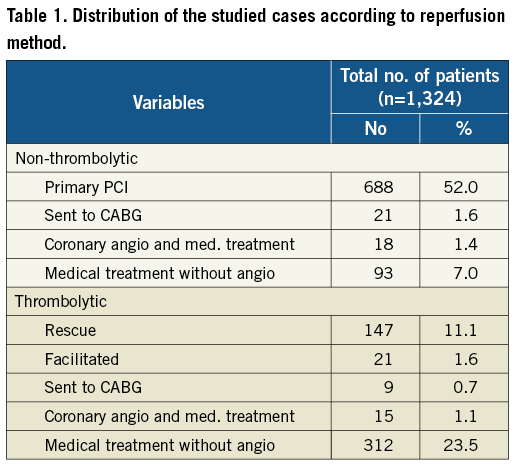

This phase was conducted at 14 centres and covered all the Egyptian regions during the period January 1st, 2011 to November, 2011 (Figure 3 and Figure 4). A total of 1,324 consecutive patients presenting with STEMI: 688 patients presented within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms underwent primary PCI, 504 patients received thrombolytic therapy; 312 patients of them did not undergo coronary angiography after that, 147 patients underwent rescue PCI within 12 hours after failed thrombolytic therapy, 21 patients underwent facilitated PCI, 33 patients underwent coronary angiography and continued on medical treatment while 30 patients sent to CABG and 93 patients did not receive any reperfusion therapy (Table 1).

Figure 3. Participating Egyptian centres.

Figure 4. Egyptian Pilot centres according to population.

All patients were subjected to detailed history taking, clinical evaluation, ECG analysis and chest pain-to-ER, door-to-balloon, time from the end of failed thrombolytic therapy to the rescue PCI were computed in and given in minutes. Coronary angiography and PCI procedure were described including materials used. In-hospital mortality was also documented.

Cardio Egypt 2012

As one of the major events in Cardio Egypt’s 39th conference, the board of the Egyptian Society of Cardiology held a meeting with the Minister of Health and Population and the ministry representatives; Dr Sobhy spoke briefly about the idea of the project and the progress we had achieved until then. There was an open exchange of ideas as well as a fruitful discussion.

The Egyptian Minister of Health and Population showed his appreciation by supporting the project with several actions / steps:

– The ministry agreed to cover the expenses of operating primary PCI in a retrospective way for the patients who will be diagnosed with ST-elevation after the approval of the Tripartite Committee in the centre or hospital that fits the criteria for SFL centres.

– A protocol was determined for those patients who can be saved during the first hours using catheters or stents in the selected hospitals

– A control of all the preparations in the ambulance cars as well as supporting them with ECGs.

– The provision of ambulance cars and preparing them for serving centres selected to participate in the project.

– Training the paramedics for operating echocardiography and diagnosing ST elevation.

– Rapid transmission of the ECG to doctors.

– Support of public awareness campaigns and providing media coverage.

Prague meeting

As a result of this successful meeting, another was held in Prague between the project’s board and doctors participating in data entry as well as representatives from different sectors within the Ministry of Health. The goal of these discussions was to ensure more interaction in relation to the actual goal of the project in order to enhance the exchange of information and experience.

Dr Ahmed El Shal, the project manager, arranged for the participation of 84 referral physicians in this meeting to review with the Egyptian board and European speakers all the project details as well as European practice guidelines on myocardial revascularisation.

The meeting was the first spark for introducing stent for life to medical societies other than cardiology as well as involving referral doctors in different specialties in such a project. Petr Widimský explained to the audience how the project was born.

The second phase registry began in February 2012 with completion scheduled for February 2013. The objectives of this phase was to see the impact of attempting to solve all the obstacles as well as all the activities held at every level (physician education programmes, patient awareness campaigns, paramedic training, MOH participation, ambulance updating) of the project in order to see whether the percentage for STEMI patients receiving operations on time could be raised from 8% to 23% and door to balloon time decreased.

Statistical analysis of first phase:

Data were analysed using SPSS software package version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative data was expressed using range, mean, standard deviation and median while qualitative data was expressed in frequency and percent.

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

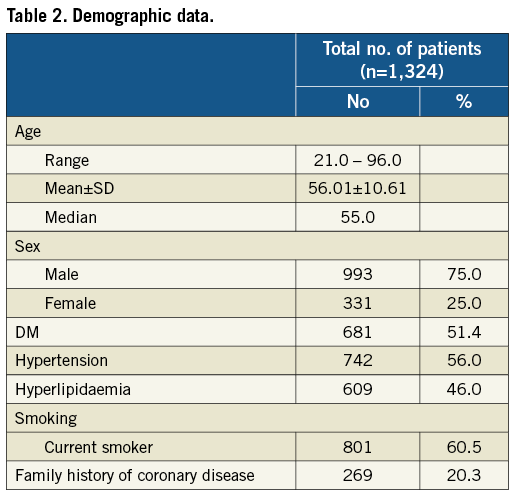

The mean age at presentation was 56.01±10.61 years and 75.0% were male. Cardiovascular risk factors were mainly smoking (60.5%), dyslipidaemia (46.0%), diabetes (51.4%), hypertension (56.0%) and heredity family coronary heart disease in 20.3% of patients (Table 2).

TIMING VARIABLES

The median time from onset of symptoms to presentation was 320 minutes in patients treated with primary PCI and 270 minutes in patients treated with thrombolysis and the median door-to-balloon time was 70 minutes in primary PCI group (688 patients). The median time between end of failed thrombolytic therapy and the rescue PCI was 420 minutes (147 patients).

PROCEDURAL-RELATED TECHNIQUES AND MATERIALS

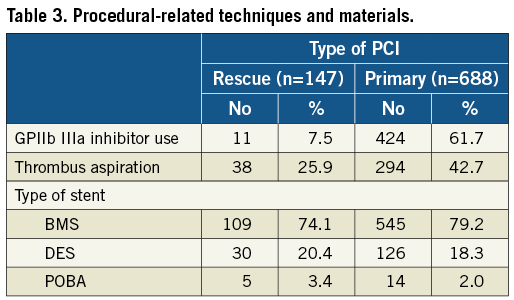

GPIIb IIIa inhibitor was used at the discretion of the operators in 61.7% of primary PCI patients and in 7.5% of rescue PCI patients. Thrombus aspiration was done in 42.7% of patients in primary PCI group and 25.9% in rescue PCI group. Bare metal stents (BMS) were used in 80.7% of the stented patients while drug eluting stents (DES) were used in 19.3% of the stented patients (Table 3).

IN-HOSPITAL MORTALITY

In-hospital mortality was 2.9% (1.4% in the primary PCI group, 1.1% in patients treated with thrombolysis and 0.4% in patients receiving no reperfusion therapy).

Discussion

Since 10 years the survival benefit of primary PCI for STEMI has been demonstrated in several randomised trials. Since then, primary PCI has been implemented in routine daily practice and is in the guidelines of the preferred reperfusion therapy for patients with STEMI10.

Although widely adopted as the default strategy for patients presenting with STEMI in developed nations, there is little data on the applicability, success and outcomes of primary PCI in third-world nations with limited follow-up11.

BASELINE CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

We found in our study that the mean age is 56 years, which is lower than the mean age in other studies published in the literature in developed countries, but more or less equal to that in studies published in third-world nations because of the pandemic of diabetes in our country which may in part be associated with the metabolic syndrome. This further underlines the urgent need for a national policy for primary and secondary prevention of diabetes and dyslipidaemia. The prevalence of smoking in our country is still high as well, despite a public health effort to limit tobacco use.

ONGOING RESEARCH AND STUDIES

Saman Rasoul et al10 studied primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI: From clinical trial to clinical practice. This study reported that from 1994 through 2004, a total of 4,732 patients with STEMI were admitted for primary PCI at the Isala Clinics (Zwolle, Netherlands). Mean age of the patients was 61 (19-95) years, 76% were male, 11% had a history of previous myocardial infarction, 11% had diabetes mellitus, 31.9% were hypertensive, 48.5% were current smokers and 44.3% were dyslipidaemic.

Y.B. Juwana et al12 studied primary coronary intervention for STEMI in Indonesia and the Netherlands. This study reported that a total of 596 patients were treated by primary PCI, 568 in Zwolle and 28 in Jakarta. Patients in Indonesia were younger (54 vs. 63 years), more often had diabetes (36 vs. 12%), high lipids (46 vs. 19%) and were more often smokers (68 vs. 31%).

Fahim H et al11 studied Outcomes of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention at a Joint Commission International Accredited Hospital in a Developing at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) in Karachi, Pakistan. A total of 277 subjects were included in this study. The mean age of the patients was 54.9±11.2 years, 76.5% were male, 32.1% had diabetes, 46.9% were hypertensive, 32.9% were current smokers, 45.8% were dyslipidaemic and 12.3% had a prior MI.

Andrew et al13 studied rescue PCI in MERLIN trial. This trial reported that 307 patients with failed thrombolysis to rescue PCI or conservative care reflects the practice of PCI performed in the United Kingdom, 153 patients undergo rescue PCI, mean age 63.0, 71% of them were male, 11.8% had history 0f DM, 40.5% had history of HTN, 19.0% had history of dyslipidaemia, 41.8% were current smoker and 11.1% had history of previous MI.

ADMISSION TIMING CHARACTERISTICS

PRIMARY PCI GROUP (688 PATIENTS)

The median time from onset of symptoms to presentation was 320 minutes and the median door-to-balloon time was 70 minutes.

Saman Rasoul et al10 reported that from 1994 to 2004, patient delay remained unchanged (3.8±4.3 h), while door to balloon time decreased significantly from (1.0±0.9 h) to (0.9±0.2 h).

Y.B. Juwana et al12 reported that time between symptom onset and hospital admission was longer in Indonesian patients (413±325 vs. 214±202 min) and time from hospital admission to balloon inflation was much longer in Indonesia than in Netherlands (189±127 vs. 49±33 min).

Sune Pedersen et al14 reported that the median door-to-balloon time was 97 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 65 to 135) and the total symptom-to-balloon time was 214 minutes (IQR, 145-310).

Busk M et al15 studied the DANAMI-2 trial reported that the median door-to-balloon time was 109 minutes and the total symptom-to-balloon time was 216 minutes. It should be noted that this data was mainly collected from inter-hospital transfer.

Abdessalem S et al16 reported that the average time of angioplasty compared with the onset of pain was 10.9±6.8 h in the total population (<24 h) and 6.6±2.6 h in the subgroup of 139 patients taken before 12 pm. Only 32.2% of patients had angioplasty in the first six hours.

Fahim H et al11 reported that the median time from onset of symptoms to presentation was 160 minutes, and the median door-to-balloon time was 90 minutes.

Petr Widimsky et al17 studied the reperfusion therapy for STEMI in Europe, description of the current situation in 30 countries, reported that the time from symptom onset to the first medical contact (FMC) ranged from 60 to 210 min and FMC-balloon time was between 60 and 177 min.

In our study the time delay between patient’s symptoms and first medical contact ranged from 30 to 720 minutes, which is considered higher than that published in the literature in many developed countries. This points to the fact that our patients should be better educated to minimise this delay through media and public awareness (Figure 5). The mean door-to-balloon time was a 68.91±23.25 minute which is more or less similar to that in many developed countries16. It has been suggested that once door-to-balloon times exceed 90 minutes, the benefits begin to decline and mortality increases.

Figure 5. Promotional material.

RESCUE PCI GROUP (147 PATIENTS)

In our study; the time from onset of pain-to-thrombolytic was 274.35±277.78 minutes, while the median time between end of failed thrombolytic therapy and the rescue PCI was 420 minutes.

Andrew et al13 reported that, the time from onset of pain-to-thrombolytic was 327±121 minutes and time between thrombolytic to rescue PCI was 146 minutes.

Gershlick et al18 studied Rescue Angioplasty versus Conservative Therapy of Repeat Thrombolysis (REACT) trial. This trial reported that 427 patients with failed thrombolysis as defined by lack of >50% resolution of ST segment changes at 90 min. 144 patients undergo rescue PCI. Pain-to- thrombolytic was 140 minutes and time between thrombolytic to rescue PCI was 274 minutes.

David et al19 studied Rescue Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Failed Thrombolysis study. In the study group consisted of 214 consecutive patients had failed thrombolysis, 178 patients (83%) undergo rescue PCI. Symptom onset to thrombolytic therapy was 5.6 hr and the mean time from thrombolytic therapy to PCI was 7.0 h.

PROCEDURAL-RELATED TECHNIQUES AND MATERIALS

GPIIb IIIa inhibitor was used at the discretion of the operators in 61.7% of primary PCI patients and in 7.5% of rescue PCI patients. Thrombus aspiration was performed in 42.7% of patients in primary PCI group and 25.9% in rescue PCI group. Bare metal stents (BMS) were used in 80.7% of the stented patients while drug eluting stents (DES) were used in 19.3% of the stented patients. POBA was applied to 5.4% of patients only.

Sune Pedersen et al14 reported that glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitor was used at the discretion of the operators in 28% of patients. POBA was applied to 6% of patients only. BMS were used in 40% of patients while DES were used in 37% of patients. Abdessalem S et al16 reported that Glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitor was used in 12% of patients. Stenting was performed in 96.2% of patients. Direct stenting was performed in 48.2% and the predilatation balloon or thrombo-aspiration prior to stenting in 44.2% and 3.8% of cases respectively.

Fahim H et al11 reported that glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitor was used at the discretion of the operators in 90% of patients. Stents were used in 96% of patient while POBA was applied to 4% of patients only. Multivessel PCI at the same setting was applied to 4.3% of patients only.

David et al19 stated that, thrombus aspiration was done in 21%. Stents were used in (88%). (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitor was administered in (92%).

IN-HOSPITAL MORTALITY

In-hospital mortality was 2.9% which is more or less similar to that in many developed countries and less than that in the developing countries due to younger mean age, shorter door-to-balloon time, fewer numbers of patients presented in cardiogenic shock and high procedural success.

Abdessalem S et al16 reported that the cumulative mortalities were 5.3% in-hospital.

Fahim H et al11 reported that twenty-three patients died in the hospital (8.3%).

Petr Widimsky et al17 reported that the in-hospital mortality of all consecutive STEMI patients treated by primary PCI between 2.7 and 8%.

In rescue PCI, David et al19 reported that hospital death occurred in 3.4%.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Our registry is not without limitations. First, the delay-to-PCI comprises the time taken by patients to decide whether they can proceed with the procedure, based on financial constraints. Second, our use of historical data to compare our experience with Western outcomes carries obvious limitations and is by no means definitive. There are many differences both in patient characteristics (age in our study was lower than in the other studies; on the other hand, time from symptoms to first medical contact was higher) and selection methods. Nevertheless, we feel that our data do enable us to make the point that outcomes similar to the West may be possible in developing countries, and further study, perhaps with a real-time Western comparator group, would be in order.

Conclusions

This is the first basic step in the SFL project shaping the future and deciding the successful pathways to overcome problems that prevent the introduction of the best service to patients.

As we believe in the importance of primary PCI as the mainstay in the treatment of STEMI; Egypt is currently contributing to the European project of stent for life (SFL) as a one of 10 targets countries in the next few years.

We reported initial success rate in increasing the number of patients treated with primary PCI, our results compared favourably to Western data, despite many differences in facilities and patient characteristics.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.