Abstract

Aims: Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) are used to treat acute and chronic forms of coronary artery disease. While in chronic forms the main goal of PCI is to improve the quality of life, in acute coronary syndromes (ACS) timely PCI is a life-saving procedure – especially in the setting of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The aim of this study was to describe the experience of countries with successful nationwide implementation of PCI in STEMI, and to provide general recommendations for other countries.

Methods and results: The European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) recenty launched the Stent For Life Initiative (SFLI). The initial phase of this pan-European project was focused on the positive experience of five countries to provide the best practice examples. The Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Sweden, Denmark and Austria were visited and the logistics of ACS treatment was studied.

Public campaigns improved patient access to acute PCI. Regional networks involving emergency medical services (EMS), non-PCI hospitals and PCI centres are useful in providing access to acute PCI for most patients. Direct transfer from the first medical contact site to the cathlab is essential to minimise the time delays. Cathlab staff work is organised to provide acute PCI services 24 hours a day / seven days a week (24/7). Even in those regions where thrombolysis is still used due to long transfer distances to PCI, patients should still be transferred to a PCI centre (after thrombolysis). The highest risk non-ST elevation acute myocardial infarction patients should undergo emergency coronary angiography within two hours of hospital admission, i.e. similar to STEMI patients.

Conclusions: Three realistic goals for other countries were defined based on these experiences: 1) primary PCI should be used for >70% of all STEMI patients, 2) primary PCI rates should reach >600 per million inhabitants per year and 3) existing PCI centres should treat all their STEMI patients by primary PCI, i.e. should offer a 24/7 service.

Introduction

Reperfusion therapy is the most beneficial part of the treatment in patients suffering from an acute myocardial infarction. When applied in a timely manner, it influences positively the duration of the hospital stay, number of readmissions, the risk of reinfarction, as well as both short and long term mortality. Today several modalities of reperfusion therapy are available: thrombolytic treatment (TL) (in the pre-hospital or in-hospital setting), primary percutaneous coronary intervention (primary PCI) or a combination of both. Primary PCI is the preferred reperfusion strategy in acute myocardial infarction when performed by an experienced team as soon as possible after first medical contact.1,2 The PCI reperfusion modality remains superior to immediate thrombolysis, even when transfer to an angioplasty centre is necessary.3 Primary PCI is the preferred treatment for patients in shock4, and is also indicated for patients with contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy.5 Urgent coronary angiography is also recommended for patients with refractory or recurrent angina associated with dynamic ST-deviation, heart failure, life-threatening arrhythmias, or haemodynamic instability. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI)1 and for non-ST elevation myocardial infarction6 clearly describe how the patient should be treated. On the other hand, data from several national registries and surveys indicate that the use of guidelines is not completely implemented in daily practice (GRACE, Euro Heart Survey). The most frequently used reperfusion therapy in many European countries remains thrombolysis. Of greater concern is that a large proportion of patients receive no reperfusion treatment at all.

To obtain an up-to-date, realistic picture of how patients with acute myocardial infarction are treated in Europe, a survey of all 51 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) countries was performed. The chairpersons of national working groups / societies of interventional cardiology in Europe were also invited to participate. Data were collected regarding: 1) the country and any existing national STEMI or PCI registries, 2) STEMI epidemiology and treatment in each country and 3) numbers of PCI and primary PCI centres and procedures in each country. Results from the national registries in 18 countries and surveys in nine countries were included in the analysis. This study of pan-European practices shows that far more patients receive reperfusion intervention in countries in which primary PCI is preferred over thrombolysis. Furthermore, from the latter it was shown that in “real life” interventions, the mortality reduction with primary PCI exceeds the values provided by randomised trials. Finally, these data suggest that the situation is better in countries in which primary PCI is applied for the majority of acute myocardial infarction patients, as is found in north, west and central Europe.

To improve the current situation in specific part of Europe and to achieve the optimal treatment of acute myocardial infarctions in all EAPCI member states, the leadership of the EAPCI, EuroPCR and ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care, in collaboration with EUCOMED, organised the “Stent for Life” project. The steering committee formalised the main objectives of this project. Countries in which primary PCI is used in a minority of acute myocardial infarction patients were identified and the following three targets were set: 1) To increase the use of primary PCI to more than 70% among all ST elevation myocardial infarction patients, 2) To achieve primary PCI rates of more than 600 per one million inhabitants per year, and 3) All existing primary PCI centres should offer a 24/7 primary PCI service.

This manuscript describes daily practice in five European countries (The Czech Republic, The Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Austria), in which patient triage, pre-hospital management and hospital networks are well developed. This report may serve as a guide and source of inspiration for countries working to meet the above mentioned criteria.

Organisational characteristics in countries with primary PCI services already widely implemented for the large majority of patients presenting with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction

The Czech Republic

The Czech Republic (CZ) is a relatively small, landlocked central European country. It has an area of 78,866 km2. The population in 2008 was 10,467,542. In 1989 there were only six primary PCI centres and six interventional cardiologists able to perform coronary angiography in the entire country. Between 1990 and 1996 doctors – especially young doctors – were trained in the use of this diagnostic technique and the use of PCI expanded. In the years between 1997 and 2002, two randomised, large-scale studies were conducted (the PRAGUE 1 study7 and the PRAGUE 2 study8). According to the results of these two studies, almost no thrombolysis was used after 2002. These results have influenced the thinking of all physicians regarding reperfusion therapy for acute myocardial infarctions, and contributed as well to the increased use of primary PCI.

The CZ is divided into 14 regions and now has 22 primary PCI centres with 24/7 service, hence every region now is serviced by at least one PCI centre (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The distribution of 22 primary PCI centres in 14 regions in the Czech Republic.

The most frequently used reperfusion therapy in the CZ is primary PCI (92%). Thrombolysis is given to only 1% of ST elevation myocardial infarction patients.9 There are three criteria for the use of thrombolytics: 1) patients admitted within 12 hours of symptom onset that refuse an invasive procedure, 2) patients with no arterial access, or 3) logistic problems (cathlab technical problems, weather conditions, etc.). About 7% of patients receive no reperfusion therapy, most commonly due to late presentation (>12 hours) where symptoms and ST elevations having already resolved.

Health care is paid from the health insurance system (fee per service). Insurance is compulsory by law; every citizen can choose from 10 insurance companies. In 2001, the Czech Society of Cardiology prepared the National Cardiovascular Program. This document serves as a basis for coordinated efforts for all participants in health care services leading to the establishment of an effective system of care for patients with heart and circulation diseases in the CZ. This document contains information about emergency medical services organised by the government and addresses the need for the transport of patients with acute myocardial infarction directly to PCI centres. It also establishes, according to population figures, the number of cardiologists, primary PCI and cardiac surgery centres.

There are two emergency phone numbers in the CZ. The older countrywide number (155) is well known and the new EU emergency number (112) is being widely publicised. Both are free of charge and available 24/7. Dispatchers, specially trained to deal with emergency situations (such as patients calling with acute myocardial infarction) activate emergency medical services. In smaller towns, a physician is present on the ambulance. In other districts, mostly in larger cities, a “rendezvous organisation” is established, i.e. the ambulance is staffed with specially trained paramedics and the physician meets the patient en-route to the PCI facility. Physicians are dispatched for all patients with chest pain and breathlessness, or at the request of paramedics. Every ambulance is equipped with a 12-lead ECG recorder, defibrillator, and drugs such as clopidogrel, aspirin, unfractioned heparin, opioids, beta-blockers and nitroglycerin. In addition, there is oxygen and equipment for intubation and artificial pulmonary ventilation present. An ECG is recorded as soon as possible after the initial patient contact and a diagnosis is established on site. Teletransmission of ECGs is not widely used in the CZ. In cases of ST elevation myocardial infarctions, clopidogrel (600 mg), aspirin (500 mg i.v.) and unfractioned heparin (100 IU/kg or 5000 IU bolus) are administered and the patient is transported to the nearest primary PCI centre, accompanied by an emergency medical services (EMS) physician (this is referred to as primary transport). Transport-related delays do not exceed 90 minutes; transport distances are never greater than 100 km and usually less than 50 km. In most cases, air transport offers no time advantage and therefore is rarely used having also been shown to be more time consuming as well as associated with higher costs.

The cardiologist on duty is contacted and the cathlab staff activated (usually one interventional cardiologist and one nurse); in some hospitals a trainee physician or an additional nurse is also available. Whenever necessary, staff from the intensive care unit participate as well. The interventional cardiologist is on-call and required to be within 30 minutes in the cathlab. Most cathlabs have nurses available 24/7. Patients are transported directly to the cathlab table. Patients brought to non-PCI capable hospitals (not arriving by emergency transport, e.g. taxi, personal car) are transferred directly to the cathlab of the nearest PCI centre immediately following their diagnosis (secondary transport). To reduce the delay, patients are not admitted to local hospitals prior to transfer. Every PCI centre has an informal agreement with non-PCI hospitals in the local area regarding management of acute myocardial infarction patients. After primary PCI, patients are moved from the cathlab to the coronary care unit of the PCI centre. The length of stay at the PCI hospital is one to two days assuming an uncomplicated procedure. During this time, ECG and blood pressure are continuously monitored. Blood tests, including troponins, are also taken. Additionally, every patient undergoes an echocardiographic examination. Patients from non-PCI hospitals are transported back to their local hospital. Transport is handled by the EMS and is described as tertiary transport. The main reason for returning the patient to their local hospital is the limited bed capacity in the primary PCI centres. A second reason concerns local hospital policies regarding care of patients within their districts.

According to the guidelines, patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction with heart failure, life threatening arrhythmias, recurrent, or refractory angina and ST depressions are brought directly to the primary PCI centre in a similar manner as STEMI patients. Uncomplicated non-STEMI acute coronary syndrome patients are first admitted to the nearest hospital.

The CZ uses the International Refined Diagnosis Related Groups system (DRG) for reimbursement. Every diagnosis and treatment has a specific code and corresponding payment from the health insurance companies. A PCI centre receives a fixed payment for a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction as well as for the primary PCI procedure regardless of materials used (stents, balloons, etc.). Local hospitals receive payment for the remaining hospital stay. There are no differences in reimbursement of procedures based on time (i.e. day, night, weekends or holidays). No limits are set on the number of primary PCI procedures in STEMI patients, all are fully reimbursed. Thus, primary PCI is economically attractive for hospitals. Health insurance companies play an important role in this process. Having a non-stop (24/7) primary PCI service is a “condition sine qua non” for any PCI centre to have a contract with insurance companies for PCI reimbursement. Thus all existing PCI centres in the CZ offer 24/7 primary PCI service.

The Netherlands

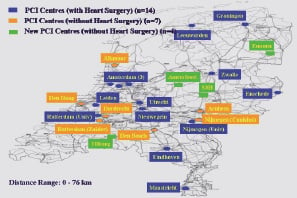

The Netherlands (NL) is located in northwestern Europe and has an area of 41,526 km2. It has an estimated population of 16,491,852. There are 21 primary PCI centres with 24/7 service in The Netherlands, and another four are under development (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of primary PCI centres in The Netherlands.

Every citizen lives within one hour of a PCI centre. Nearly all patients with STEMI are treated by primary PCI. Only a very small number of patients receive thrombolysis. These patients are usually from islands north of the mainland.

The emergency phone number is 112. Most of patients are brought to the hospital by EMS. People from The Netherlands are well aware of the emergency number. Ambulances must be able to reach patients within 15 minutes anywhere in the NL. Awareness of the emergency number combined with rapid response times means that many patients start receiving medical attention shortly after the onset of symptoms. Ten years ago, the Dutch Heart Foundation, in collaboration with The Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Ministry of Health, organised campaigns on chest pain and emergency phone number awareness. The relevant information was published primarily in newspapers, but also announced on TV and radio as well. This promotion continues to keep people aware of the 112 emergency number and the warning signs of a heart attack. Currently there is a campaign in order to increase the number of citizens with cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills and to promote the bystander use of AED.

In The Netherlands, the key to success of timely acute myocardial infarction treatment is the ambulance system, which is operated by a trained staff of a driver and one trained nurse, no physicians are present on board. The ambulance nurses and drivers are technically proficient and highly educated. Both are obliged to follow a specific ambulance training course; furthermore, most of the ambulance nurses have at least two years of intensive care experience in an intensive/coronary care unit. All the treatment in the ambulance is based on specific protocols. There are 170 protocols, two of them concern the treatment of acute myocardial infarction and the ambulance personnel work exactly according to this protocol. All ambulances are equipped with a 12-lead ECG system providing the most apparent diagnosis (in the case of STEMI, the diagnosis appears on the screen of the ECG recorder). In Amsterdam, where three PCI centres are located, the teletransmission of ECGs is used. In the teletransmission centre, the STEMI diagnosis is confirmed. Then the PCI centre is informed that a patient is on route, and the cathlab staff is activated (one interventional cardiologist, one nurse, one technician; all required to be within 30 minutes in the hospital). The index PCI centre is established based on postal codes. Every PCI hospital services the population in an area around the hospital that is specific to postal codes. During transfer, an ambulance mission form is completed. The commonly used pre-hospital medication in STEMI patients is: aspirin (500 mg i.v. bolus), unfractioned heparin (5000 IU i.v. bolus), and a loading dose of clopidogrel (600 mg tablet). GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are not used routinely in the pre-hospital setting. Patients are transferred directly to the cathlab. After the procedure, patients are transported to their local hospital the following day.

Every citizen in The Netherlands is insured. A Diagnosis Related Budget is used in The Netherlands. They have more than 40,000 combinations of diagnosis and treatment codes. The primary PCI centre receives payment for the PCI procedure and for CCU admission. The local hospital receives payment for cardiac rehabilitation. No differences exist in reimbursement of procedures based on the time of the day.

Recently, a PCI Registry has been developed. All PCI patients, including those with an acute myocardial infarction, are recorded together with data on history and reperfusion therapy. This registry serves as a quality control which is monitored by the government; postal codes play an important role in this process.

During the process of conversion from thrombolysis to primary PCI, it was very important to persuade physicians from non-PCI capable hospitals to accept the transfer of patients directly to PCI centres. Physicians from non-PCI centres were unhappy with the loss of patients with an acute myocardial infarction at their local CCU department. It was necessary to convince everyone that the transfer was in the best interest of the patient. Objections to primary PCI disappeared after data focused on short and long term mortality were published. It is very clear, that primary PCI confers a significant additional survival benefit. This has been the basis for convincing health care providers and government representatives.

Sweden

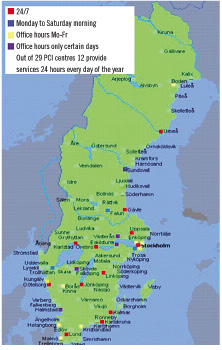

Sweden (SE) is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in northern Europe. At 449,964 km2, Sweden is the third largest country in the European Union in terms of area, and has a population of 9,234,209. While the overall population density of Sweden is rather low (20 inhabitants per km2), it has a considerably higher density in the southern half of the country. About 85% of the population live in urban areas. Primary PCI is the most frequently used reperfusion therapy in Sweden. There are 29 primary PCI centres, the majority of them works on a 24/7 schedule (Figure 3).

Figure 3. PCI centres in Sweden, with the indicated operating time.

In the northern part of Sweden, where a minority of population lives, there are very large distances to contend with. Transfer to primary PCI centres in a timely manner is sometimes not possible, and the reperfusion strategy in this part of the country is still thrombolysis (country-wide it was 6.2% of all STEMI patients in 2008). Air transport is used only for patients living on islands in the Baltic Sea, and sometimes in the northern regions, depending on weather conditions and helicopter availability.

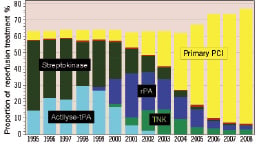

A few years ago the dominant reperfusion therapy in STEMI patients was thrombolysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Change in reperfusion treatment in STEMI /LBBB patients younger than 80 years in Sweden between the years the 1995 and 200813.

The change to the new reperfusion treatment was a team effort from the beginning. PCI centres invited physicians from other hospitals in their region and the EMS heads to discuss every step. Over time, better outcomes with primary PCI persuaded physicians, and they agreed with this new approach. In Sweden, it is necessary to have convincing scientific evidence for all changes. Based on data, political decisions are made and supported economically. Finally, changes are implemented in daily practice. The Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA)10, collects data about all acute coronary syndromes in Sweden. Data from this registry are periodically evaluated and provided to politicians. On the basis of these results, they try to change daily practice and improve quality of patient care. Also, a quality index has been developed; it scores hospitals based on how well they perform on nine different criteria in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction patients. One of these criteria is the percentage of STEMI patients receiving any reperfusion therapy; a second one is the time delay-to-reperfusion. Mortality is also monitored. Hospitals with a low quality index undertake a plan of action to improve treatment quality. Results of these evaluations are popularly followed, making newspaper, TV and radio headlines.

About 80% of patients are brought to hospitals by the EMS. This high proportion is achieved by repeated awareness campaigns. At least once a year results of new clinical trials are presented on local TV and newspapers. At the same time, campaigns that inform people about the necessity of ambulance transport in cases of chest pain are also publicised. Signs concerning this are displayed in public places (buses, phone boxes, etc.).

The emergency phone number in Sweden is 112. There are no physicians on board ambulances in Sweden. Ambulances are staffed with specially trained nurses and are all equipped with ECG recorders (with teletransmission potential), defibrillators, with every patient receiving an intravenous line. An ECG recording is performed immediately following first patient contact and a central evaluation of the ECG is used with all ECGs from ambulances being transmitted directly to the PCI centre in which treatment decisions are made. All ECGs are checked by a CCU nurse, and in case of doubt or pathologic ECG, by a CCU physician as well. The ECG, blood pressure, saturation and respiration frequency are transmitted (once per minute) from the ambulance. The primary PCI centre staff is thus aware of the patient’s status and development before the arrival of the ambulance. Aspirin (300 mg), oxygen, nitroglycerin and morphine may be administered without prior physician consultation. Nurses in the ambulance have to complete a reperfusion check list. Among other things, it contains questions about any prior history of bleeding. Additional drugs (unfractioned heparin, a loading dose of clopidogrel, beta blockers, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, etc.) can only be given on the basis of a physician’s prescription (communicated to the nurse in the ambulance by phone, as well as through the on-board computer system). An exception is the Östergötland region, where about 70% of all STEMI patients in this region receive abciximab instead of clopidogrel in the pre-hospital phase. Patients are transported directly to the cathlab where the cathlab staff (one interventionist and two nurses) has been activated by the EMS (they are required to be within 30 minutes of hospital while on call). During the primary PCI procedure, a CCU cardiologist is present in the cathlab. The mean CCU stay in PCI centres, in uncomplicated cases, is 24 hours. Patients are then referred to their respective local hospital. Clopidogrel is recommended for bare metal stents for three to 12 months; for drug eluting stents for 12 months.

In regions in which thrombolysis is administered, coronary angiography is performed in the event of unsuccessful reperfusion. In case of successful treatment, subsequent stress tests are performed.

There are no health insurance companies in Sweden. The health care service is tax financed. Patients pay only a symbolic amount of eight euros per in-hospital day. Hospitals receive their budget from the government for one year periods. To avoid year-end budget shortfalls, physicians, in cooperation with the management, must manage the limited amount of money very economically.

Denmark

Denmark (DK) is a Scandinavian, northern European country with a total area of 43,098 km2 and a population of 5,511,451. Primary PCI, as the routine reperfusion treatment for almost all STEMI patients, was implemented after results from the DANAMI 2 trial were published. This study involved doctors from non-PCI hospitals, whose involvement alone greatly influenced their future behaviour regarding treatment of STEMI patients. During the study, cathlabs were equipped with both technical and personal facilities and improvements in ambulances were undertaken. Even into the late 1990s, ambulances were staffed with personnel having only very modest levels of medical education. The protocol of the DANAMI 2 study led to safe transportation of patients either accompanied by doctors, or transferred in ambulances with trained nurses; in some regions, a “rendezvous” set-up has been introduced, while in others, a trained physician is still to be found on-board.

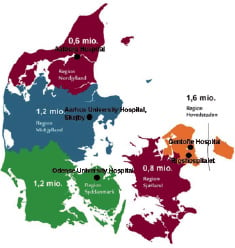

There are five centres for primary PCI procedures with a 24/7 service in Denmark (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The 5 primary Danish PCI centres in 2009.

The vast majority of the Danish population is living within two hours of a PCI centre. There are a few, very distant, rural areas in Denmark where it is difficult to reach a cathlab within a reasonable time period, but with the current logistics, thrombolysis is almost never used. For patients living on islands which pose serious transportation delays, helicopters are used.

The emergency phone number in Denmark is 112. After arrival of the ambulance, the patient’s ECG is recorded and than teletransmitted using a mobile phone network to the respective telemedicine centre. The ECG is then checked by the cardiologist on duty and the diagnosis is confirmed. In a few cases, the patient is first transported to the nearest hospital where they can be seen by a physician and then transferred to a primary PCI centre. All ambulances are equipped with defibrillators, and patients receive an intravenous line. In the ambulance, aspirin (300 mg i.v.), unfractioned heparin (10.000 IU i.v. bolus) and a loading dose of clopidogrel (600 mg) are administered. Patients are transported directly to the cathlab where activated clotting time is measured. GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are restricted for cathlab use only.

The cathlab staff is on-call and required to be ready in the cathlab within 30 minutes. The staff consists of one interventional cardiologist and two to three nurses. After the procedure, the patient is hospitalised in the CCU and is sent back to the referral hospital the following day. Clopidogrel is indicated for 12 months in all patients. On discharge, patient data are recorded in a primary PCI registry.

Uncomplicated, non-STEMI acute coronary syndrome patients are transported to local hospitals. Coronary angiography and (if indicated) revascularisation is performed within 72 hours in most patients. Patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction with heart failure, life threatening arrhythmias, recurrent, or refractory angina are brought directly to the primary PCI centre in a similar manner as STEMI patients.

The Diagnosis Related Group System is used for reimbursement in Denmark. All care is covered by the national health insurance financed by the tax-system. There is no difference in reimbursement of procedures performed based on time of day; however shift differentials are paid to physicians and nurses.

A few years ago, an awareness campaigns for patients was conducted. It was supported by the Danish Society of Cardiology and the Danish Heart Foundation in collaboration with the Ministry of Health.

Austria

Located in central Europe and occupying an area of 83,872 km2, Austria (AT) has a population of 8,316,487 and includes much of the mountainous territory of the eastern Alps (about 75% of the area), particularly in the southern and western part. However, most of the Austrian population lives in urban areas.

During the last five years, original networks for STEMI patients were developed in Vienna and many of the provincial capitals. Because of the geography, there are still regions that use thrombolysis as the primary reperfusion modality. However, the most frequently used reperfusion therapy is primary PCI (e.g. in 80% of patients in Vienna). There are 23 primary PCI centres with a 24/7 service in Austria. Improvements in health care have emerged through a close collaboration between emergency medical services, non-PCI capable hospitals and PCI centres. There are annual meetings involving all care providers in order to discuss issues concerning transportation and organisation. Treatment delays have been reduced by improving the secondary transport system. The longest delays are still patient-related. In order to combat this, campaigns on television, radio and newspapers have been organised.

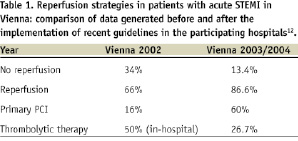

We present the “Vienna Model” of diagnosis and triage of patients with acute STEMI in a large metropolitan area which has been associated with a significant improvement in clinical outcomes over a very short time12 (Table 1).

At the end of 2002, only one primary PCI hospital with 24/7 service was present in Vienna. Reorganisation began in March 2003, with the implementation of a central triage for STEMI patients, instituted by the Viennese Ambulance System (VAS). The next step was the establishment of an additional primary PCI centre for nights and weekends. The Allgemeines Krankenhaus der Stadt Wien (AKH) university hospital is the only hospital in Vienna offering primary PCI services 365 days a year. A second catheterisation laboratory now opens in the afternoons (Monday through Thursday, 16:00 to 7:30 and Friday from 13:00) based on a rotation system between the four non-academic hospitals. The third step in this reorganisation process provided guidelines for thrombolytic therapy; in the pre-hospital or in-hospital setting, where it should only be used if primary PCI is unlikely to be available within recommended time intervals. Additionally, a prospective registry was established for control and quality assurance purposes.

Patients with chest pain can dial one of the two emergency numbers: 144 or 112. In Austria, ambulances are generally staffed with physicians, but a “rendezvous” logistic is sometimes used. The primary diagnosis and triage of patients to either primary PCI or pre-hospital TL is made by physicians of the VAS. Every ambulance is equipped with a 12-lead ECG monitor, defibrillator, and all patients receive an intravenous line. An ECG is recorded as soon as possible, and a diagnosis is made on-site. The cathlab staff (one interventional cardiologist, two nurses, and one radiology technician, all hospital based, i.e. not on call) is activated by the ambulance physician. Teletransmission is not readily available; however a teletransmission project has been recently started in Styria and Salzburg. Because physicians are part of the VAS personnel and can diagnose an acute myocardial infarction taking the appropriate actions, there is no consensus on the necessity of ECG teletransmission at the present time. Routine pre-hospital medication for patients with STEMI include: aspirin (250-500 mg i.v.), and unfractioned heparin (60 IU/kg, up to 4000 IU i.v. bolus). Administration of clopidogrel is done at the discretion of the physicians, although mostly administered in the hospitals. All necessary drugs and devices are present in the ambulance. To shorten transportation related delays, patients are transported directly to the cathlab. It is especially important in large facilities such as the AKH university hospital, where in-hospital transport may lead to unacceptable delays. The mean CCU stay after a primary PCI procedure is two days and is followed by tertiary transport to a local hospital. Clopidogrel is recommended for 12 months.

In the western and southern parts of Austria there are numerous mountains and valleys. Despite the terrain, the longest transport distance is less than 120 km, yet the transport time required for this distance can be complicated by terrain and other conditions. The decision as to what reperfusion therapy to use depends on the availability of helicopters. In patients presenting shortly after symptom onset, pre-hospital thrombolysis is initiated. The patient is than transported to the nearest hospital. After thrombolysis, angiography is performed within 24 hours.

Non-STEMI patients are hospitalised in the nearest hospitals. They receive aspirin, clopidogrel and low-molecular weight heparin (preferably enoxaparin). After stabilisation, coronary angiography is performed according to an early invasive strategy (<72 hours), whenever possible.

In Austria, the health care system is based on a modified DRG system (similar to the Czech Republic).

Lessons learned, practical recommendations for primary PCI implementation

The practical experience of the five above mentioned countries is supported by similar experiences in several other European countries (Slovenia, Norway, Poland, Germany, Switzerland, Croatia and Hungary) in which primary PCI became recently the dominant reperfusion strategy for patients with STEMI. The choice of the five countries we discuss here, as a “positive example” of nationwide implementation of primary PCI, is based on their pioneer contribution through randomised trials comparing primary PCI with thrombolysis (NL, CZ, DK), or the excellent registries they have developed (SE, AT).

Public campaigns

Wide population knowledge about acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris symptoms, about the absolutely key role of time (every minute counts), about the unique national emergency phone number, about acute myocardial infarction treatment (including primary PCI) and about cardiopulmonary basic resuscitation is probably the most important part of the entire process. The experience (especially from The Netherlands) shows, that wide knowledge in the population is capable of dramatically improving the situation.

Emergency medical services (EMS)

The experience shows that well trained nurses or paramedics may achieve similar effectiveness as physicians in the triage and transport of AMI patients. In other words, the EMS staff training is more important that the EMS staff structure, which can reflect the situation in each country. All EMS ambulances should be “equipped” with resuscitation facilities, necessary medications including infusions and by a portable 12-leads ECG. Implementation of ECG teletransmission to the PCI centre may be decided locally. In countries (or regions) with physicians on board of EMS ambulances, ECG transmission may be considered redundant or even time consuming. In countries without physician staff in the EMS ambulances, the ECG teletransmission algorithm is more frequently used, however, waiting for ECG reading in the PCI hospital should not delay the transportation. Air (EMS helicopter) transport is generally considered to take more time (due to related logistics) than road (EMS car) transport; hence road transport is usually preferred. The situation might be different in mountainous regions, on islands or in large, scarcely populated regions, in which helicopter transportation is generally faster.

Networks and infrastructure

The formation of regional networks, involving EMS, non-PCI hospitals and PCI centres, is necessary to implement primary PCI services effectively. Such regional networks should cover an area comprising a population of approximately 0.5 million (0.3-1 million) people. The delineation of smaller areas create a suboptimal workload and thus suboptimal effectiveness, while larger areas may cause PCI centre overload by acute patients. The regional network should have a formal coordinating body (e.g. steering committee), organising yearly meetings, providing treatment protocols, etc. Obviously, the network should work to “please all” (patients and all network members). This can be achieved only by respecting the right of local hospitals and local cardiologists to take care of their patients after primary PCI is completed and the patient is stabilised (tertiary transport to the local hospital nearest to patient’s home). All PCI centres should provide non-stop (24/7) services for primary PCI. PCI hospitals, which are not able to provide non-stop (24/7) primary PCI services, should not be part of the network and, in general, should not be the part of the health care system at all. Non-PCI hospitals should have a qualified cardiologist available 24/7 to be able to provide appropriate care for AMI patients.

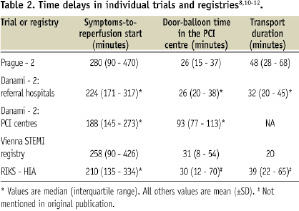

Transport, time delays

The primary transport (transport by EMS from the first medical contact site to the hospital) of STEMI patients should always bypass the nearest non-PCI hospital as well as the Emergency Room or Intensive Care unit in the PCI centre. The patient must be taken from the EMS car directly to the cathlab. The latter may be accomplished only when the cathlab is informed in advance about the STEMI patient on route. Thus, immediately after STEMI diagnosis is established the cathlab should be informed, including the approximate arrival time of the patient to the cathlab. Using this approach, time delays are minimised and the guideline-recommended limit (<90 minutes) can be achieved for the vast majority of patients (Table 2).

If the patient is initially taken to the non-PCI hospital, and from there to the PCI centre (secondary transport), at least 30-60 minutes are usually lost. If the patient is initially taken to the Emergency Room or Intensive Care Unit of the PCI centre and forwarded to the cathlab, another 20-40 minutes are lost.

Cathlab staffing, organisation of cathlab work

Interestingly, there is a large variation of the cathlab staffing for primary PCI services outside of working hours (nights, weekends).

The economic approach is represented by one cardiologist (on call outside the hospital) + one nurse (staying in the cathlab 24/7), with additional staff (whenever necessary) coming from the Intensive or Coronary Care Unit. Thus, two extra staff members are paid for primary PCI services outside of the regular working hours in this economic approach.

The extensive approach is represented by one cardiologist + one trainee physician + two nurses + one technician. Thus, five extra staff members are paid for primary PCI services outside the working hours in this extensive approach. The number of personnel can be decided locally – with only one important caveat: at least one nurse should be present in the cath-lab 24/7 in order to be able to prepare the cathlab, material (and patient) during the time when the interventional cardiologist is on the way. Those staff members, who are allowed to stay outside the hospital (on call), should be able to arrive to the cathlab within 30 minutes from being called.

Financial aspects

Reimbursement for hospitals does not seem to be a problem in most countries in which the DRG system (fee for service) is used. Hospitals in such countries are motivated sufficiently to perform primary PCI in all patients with AMI. Also, in a government-run systems, where professionals have succeeded in convincing politicians about the benefits of primary PCI (Sweden), the system was successfully implemented. Remuneration for cathlab staff (extra payment for the work performed during the off-hours) has to be set locally to a level which will motivate the existing (available) staff to work nights and weekends on top of their normal working hours. Another option may be to increase the cathlab staff numbers to a level allowing coverage of 24/7 services on a rotational principle.

CAG after thrombolysis

For the treatment of STEMI, thrombolysis was used very seldomly in four of the five selected countries. Austria is an exception, with thrombolysis use in about 20% of patients. It is debatable whether any thrombolysis can be justified today in a large city with several PCI centres (e.g. Vienna). However, there is no doubt that thrombolysis remains a viable alternative reperfusion therapy for regions with long transfer times to PCI centre (e.g. the mountainous area of Austria and the extreme northern part of Sweden). These patients (i.e. those treated initially by thrombolysis, preferably pre-hospital) should be transported as well to PCI centres, either for immediate coronary angiography (CAG), if thrombolysis is unsuccessful or if there is any doubt about its effect, or for CAG between three to 24 hours after thrombolysis. As a result, 100% of STEMI patients in each country should be admitted to a PCI centre within the first 24 hours. The large majority of them via the “primary transport” (directly to cathlab), a small minority via the “secondary transport” (after successful thrombolysis).

High risk non-ST elevation ACS

The ESC guidelines for non-ST-elevation ACS recommend performing emergent CAG (±PCI) within two hours of diagnosis in the highest risk patients with this diagnosis, specifically: ST-depression AMI with ongoing or recurrent chest pain, non-STE ACS with signs of heart failure or cardiogenic shock and in non-STE ACS patients with significant arrhythmias. Thus, these patients should be transported to PCI centres in a similar manner to STEMI patients.

Political issues

Close cooperation between the national societies of cardiology, governments (health ministries), health care financing organisations (insurance companies, public health funds), hospitals, emergency medical services and other related bodies is very effective in achieving the appropriate implementation of primary PCI programs. Formalised “National Cardiology Programs” or similar documents describing the needs, requirements or recommendations on a national level may provide support to combining and coordinating the effort of all stakeholders in this process.

Registries, quality control

National ACS (or AMI) registries are an important tool to describe the incidence, treatment and outcomes of hospitalised patients with this potentially deadly illness. Lessons learned from these registries help to further improve the system and obviously serve as quality control.

Conclusions

The feasibility of offering primary PCI for the vast majority of STEMI patients in Europe has been shown by its widespread implementation in several European countries with both differing gross national products as well as health care systems. It thus become an obligation for professionals to turn this possibility into reality. The experience in Vienna demonstrates that once the will exists and the decision about implementation of primary PCI is taken, the necessary changes in treatment organisation can be accomplished within less than two years.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions / EuroPCR and EUCOMED.