Introduction

In ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), early restoration of blood flow, preferably by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI), is paramount to limit infarct size (IS) and improve long-term outcomes1. However, reperfusion by itself may also cause damage to the myocardium and increase IS. This has been termed myocardial reperfusion injury2.

In animal models of acute myocardial infarction, it has been demonstrated that hypothermia decreases IS3. In contrast, human studies applying systemic cooling methods have not yet been able to confirm this protective effect. Recently, we developed a new method to provide selective intracoronary hypothermia during PPCI4. The EUROpean Intracoronary Cooling Evaluation in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (EURO-ICE) trial will assess the efficacy of this method.

Methods

STUDY OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of the EURO-ICE trial is to evaluate the effect of selective intracoronary hypothermia (SIH) on IS.

STUDY DESIGN

EURO-ICE is a prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled, proof-of-principle study. Two hundred patients with anterior wall STEMI and an occlusion of the proximal or mid left anterior descending (LAD) artery with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0 or 1 will be randomised in a 1:1 fashion to SIH during PPCI versus standard PPCI. The study flow chart and a complete overview of all inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1, respectively.

SELECTIVE INTRACORONARY HYPOTHERMIA

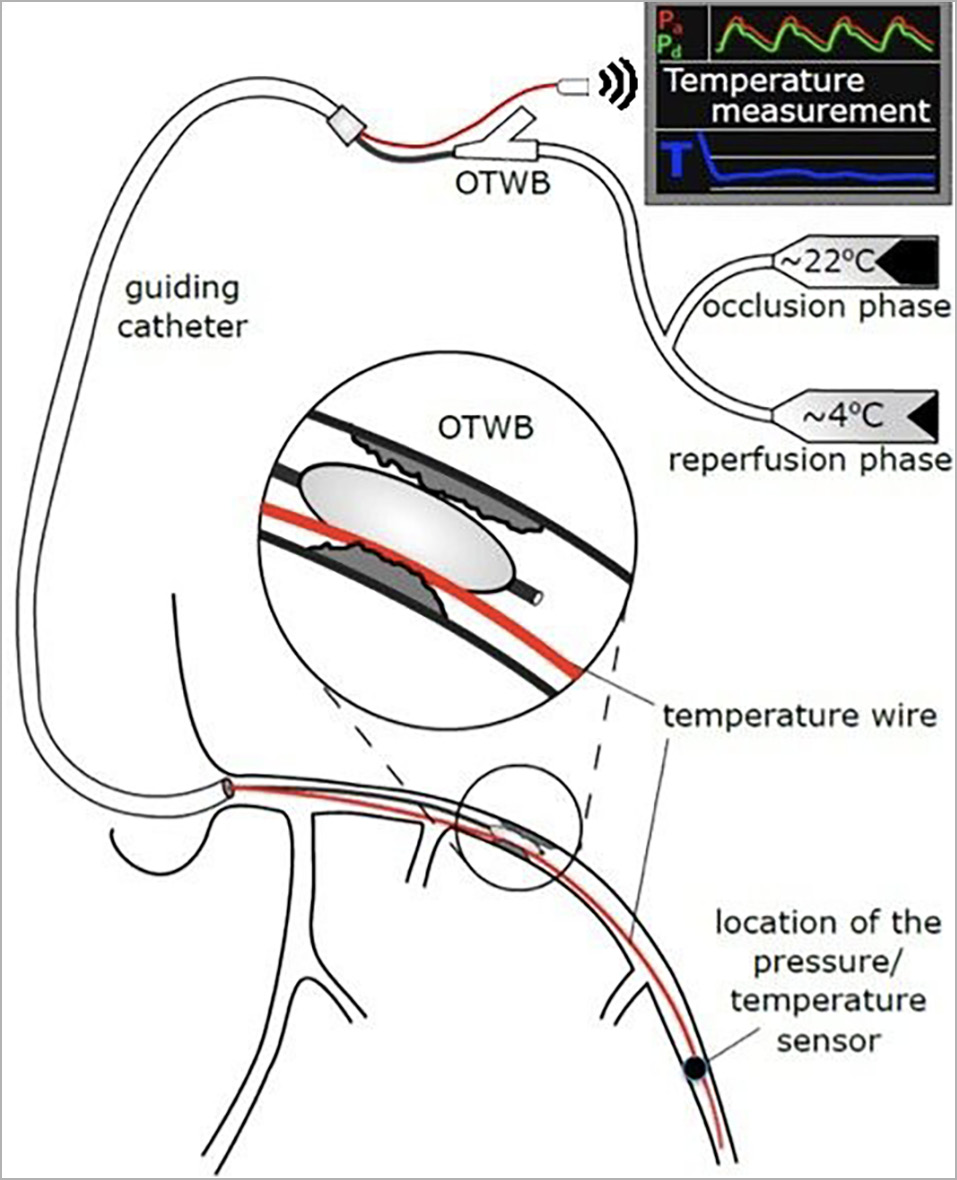

When randomised to the experimental arm, SIH will be performed as described by Otterspoor et al4. First, the occlusion is crossed with a regular guidewire. Thereafter, an over-the-wire balloon (OTWB) is advanced into the LAD artery and inflated at the site of the occlusion. Next, a pressure/temperature wire (PressureWire™ X; Abbott, St. Paul, MN, USA) is advanced into the distal LAD for continuous recording of pressure and temperature. It may be necessary to deflate the OTWB for a short period of time to get the pressure/temperature wire past the balloon. After the guidewire is removed from the central lumen of the OTWB, this lumen is connected to two infusion pumps filled with saline at room temperature and 4°C, respectively (Figure 1, Supplementary Appendix 1).

Figure 1. Schematic drawing of the instrumentation for selective intracoronary hypothermia (adapted from Otterspoor et al4, with permission). OTWB: over-the-wire balloon catheter

First, saline at room temperature is infused for 7-10 minutes at a flow rate of 15-30 mL/min (occlusion phase) to maintain a distal coronary temperature of 6-8°C below body temperature. Next, the OTWB is deflated and the infusion continues for 7-10 more minutes, using the second infusion pump filled with saline at 4°C (reperfusion phase). The flow rate can be varied to maintain a distal coronary temperature of between 4 and 6°C below body temperature.

Finally, the OTWB is retracted and the procedure continues as per routine with placement of a drug-eluting stent(s).

ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint of the study is infarct size as a percentage of left ventricular mass after three months assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, using late gadolinium enhancement analyses. Evaluation of the primary endpoint will be performed in the Glasgow Imaging Core Laboratory by experienced reviewers, blinded to the treatment allocation of the patients.

Key secondary endpoints are a composite of all-cause mortality and hospitalisation for heart failure at three months and at one year. A complete overview of all endpoints is shown in Supplementary Appendix 2 and Supplementary Appendix 3.

SAMPLE SIZE AND STATISTICS

Since this study only includes patients with anterior wall STEMI due to a proximal or mid LAD artery occlusion, we assume that IS in the control arm will correspond to a mean of approximately 25% of left ventricular mass5. Assuming a normal distribution of IS with a mean of 25% in the control arm and a standard deviation of 15%, plus typical statistical assumptions (unpaired, two-tailed t-test, alpha of 0.05, power 0.80), a sample size of 91 subjects per arm is sufficient to detect an absolute reduction of 6.25%, i.e., a relative reduction of 25%. To account for patients lost to follow-up, 200 patients will be enrolled.

The secondary endpoints of three- and 12-month clinical outcomes will be compared by applying a chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test to a 2×2 table of binary events/group. Similarly, for the secondary endpoints involving imaging or blood samples, an unpaired, two-tailed t-test or Mann-Whitney U test will be used to compare values between the groups.

ORGANISATION/ETHICAL CONCERNS (Supplementary Appendix 4)

The study protocol is approved at each participating centre by their local ethics committee and/or internal review board. All investigators will adhere to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

An independent data safety and monitoring board (DSMB) will oversee safety and a blinded interim analysis of IS will be performed after 40 patients have been included and thereafter as judged appropriate.

Discussion

Despite early revascularisation through PPCI in patients with STEMI, large infarctions still occur frequently. Consequently, mortality after STEMI remains high and many patients develop complications such as heart failure5.

A logical target for therapy beyond PPCI is the attenuation of myocardial reperfusion injury. In contrast to preclinical studies, human trials applying systemic cooling have failed to demonstrate a decrease in IS, most likely due to an inability to reach the therapeutic target temperature before reperfusion.

SIH overcomes most limitations of systemic cooling. Hypothermia is administered selectively into the infarcted area, with a rapid and sufficient decrease of the myocardial temperature before reperfusion occurs (Supplementary Appendix 5).

After having tested this method in a small safety and feasibility pilot study in humans4, we have designed the EURO-ICE study.

Limitations

Importantly, although the procedure will be prolonged by approximately 20 minutes in the experimental arm, ischaemic time will be prolonged by only 7 to 10 minutes. The hypothesised beneficial effects of hypothermia should at least counterbalance the prolongation of the ischaemic time.

Conclusions

The EURO-ICE trial is a European multicentre, randomised controlled, proof-of-principle study comparing SIH during PPCI with standard PPCI in 200 patients with anterior wall STEMI.

|

Impact on daily practice The EURO-ICE trial investigates whether SIH during PPCI decreases IS. If such a beneficial effect can be demonstrated, this will translate into a lower risk of complications, such as heart failure and mortality, and will be a next step in PPCI for patients with STEMI. |

Funding

The EURO-ICE trial is an investigator-initiated trial without any commercial purpose or pursuit of profit by the sponsor of the study, Cathreine B.V. The trial is financed by a research grant from Abbott. Their support remains limited to funding only, with no influence on study design, data collection or analysis, or final manuscript publication.

Conflict of interest statement

B. De Bruyne reports grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, and St. Jude Medical, and receives consulting fees from St. Jude, Abbott, Opsens, and Boston Scientific, outside the submitted work; he has equity in Siemens, GE, Bayer, Philips, HeartFlow, Edwards Lifesciences and Celyad. T. Engstrom reports personal fees from Bayer, BMS and Abbott, outside the submitted work. C. Berry reports grants from Abbott, Siemens Healthcare and Coroventis, outside the submitted work. N. Pijls reports consultancy fees from Abbott and Opsens, institutional grants from Abbott and Hexacath, outside the submitted work, and has equity in Philips, ASML, HeartFlow and GE Health. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.