Abstract

Aims: Left main interventions require optimal initial results for good clinical outcome. Lesion preparation with the AngioSculpt Scoring Balloon (ASB) combined with the provisional T-stenting technique, if proven safe, might lead to better lumen gain and better clinical outcome. The aim of this registry was to investigate the safety and efficacy of the ASB as an option for lesion preparation in unprotected left main interventions (ULMI).

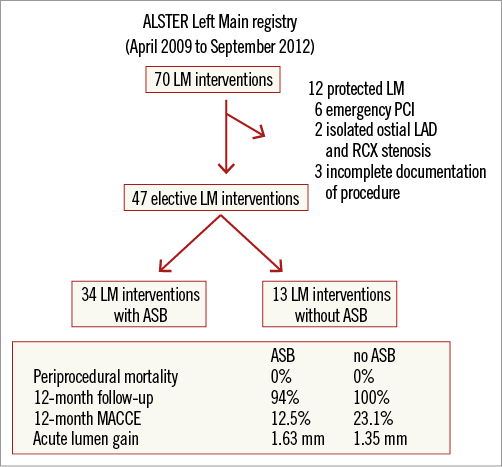

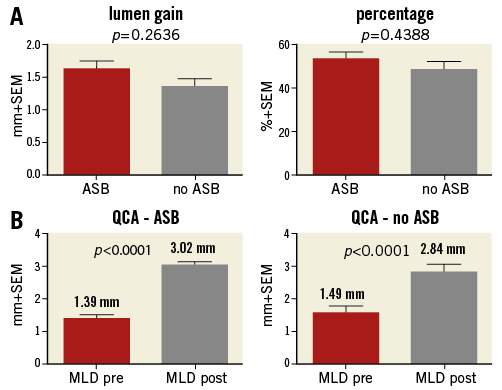

Methods and results: Out of the all-comers unprotected left main registry (ULMI ALSTER), 47 patients with elective ULMI fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this study. The endpoints were acute lumen gain and 12-month MACCE. The drop-out rate was 4%. The provisional T-stenting technique was used in 97% of distal ULMI. The interventions were grouped according to use of ASB with an in-house, historical no-ASB patient control group. Lumen gain was 1.63±0.12 mm in the ASB group (n=34) and 1.35±0.12 mm in the no-ASB group (n=8, p=0.26), respectively. The use of the ASB was safe. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) data for 21 patients showed numerically greater lumen area gain of 3.14±0.33 mm2 in the ASB group compared to 2.33±0.88 mm2 with the conventional technique. TLR/TVR was 6.6% overall. Twelve-month MACCE was 12.5% (4/32) for ASB and 15.4% (2/13) in the historical control group.

Conclusions: Adding ASB lesion preparation to the standard provisional T-stenting technique for ULMI is feasible and safe. Low TLR and TVR rates were observed. Lesion preparation led to a numerically larger lumen gain; the data allow valid power statistics to show this approach as leading to improved outcome in a possible randomised trial.

Abbreviations

ASB: AngioSculpt Scoring Balloon

IVUS: intravascular ultrasound

LM: left main

MACCE: major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

SB: side branch

ULM: unprotected left main

ULMI: unprotected left main intervention

Introduction

Fifty percent and greater narrowing of the left main (LM) coronary artery is found in about 5-7% of all patients who undergo coronary angiography1. A left main stenosis is associated with a multivessel coronary artery disease about 70 percent of the time1. Advances in transcatheter techniques, pharmacological therapy as well as drug-eluting stents (DES) have led to the long-term success of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) as a viable alternative to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) for unprotected left main disease2-4. The newest guidelines give PCI as well as CABG a class IB recommendation for LM stenosis in patients with a SYNTAX score ≤225. Current data support provisional T-stenting as the primary strategy for distal left main stenosis. Recent technical advances which may optimise clinical outcomes in ULMI have been introduced with the “proximal optimisation technique” (POT)6-8. While POT emphasises aggressive post-dilatation for good stent strut apposition and luminal gain, lesion preparation is a strategy that emphasises predilatation with specialised technical equipment to achieve maximal lumen gain and optimal stent apposition. Independently of the techniques, post-stent luminal area is an important predictor of long-term outcome9.

The aim of this registry was to investigate the safety and efficacy of the AngioSculpt Scoring Balloon (ASB) (AngioScore, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) as an option for lesion preparation in unprotected left main interventions (ULMI). Quantitative coronary analysis (QCA) was used to evaluate acute lumen gain. IVUS data were available for a subset of patients. Clinical follow-up was performed at six and 12 months after LM intervention.

Methods

The ALSTER Left Main registry included 70 consecutive left main interventions between December 2009 and September 2012 at our centre. All interventions were reviewed retrospectively to identify those with an angiographic de novo LM coronary lesion of >50% diameter stenosis leading to PCI. PCI were performed in patients with a low or intermediate SYNTAX score while patients with a high SYNTAX score were referred to surgery. Periprocedural mortality (0-30 days), procedural details, acute lumen gain and follow-up at six and 12 months were reviewed. The LM was considered to be unprotected in the absence of any patent coronary bypass grafts to either the left anterior descending artery (LAD) or the left circumflex artery (LCX). Exclusion criteria for this population were an emergency PCI due to an acute myocardial infarction or cardiogenic shock or a PCI in combination with a TAVR.

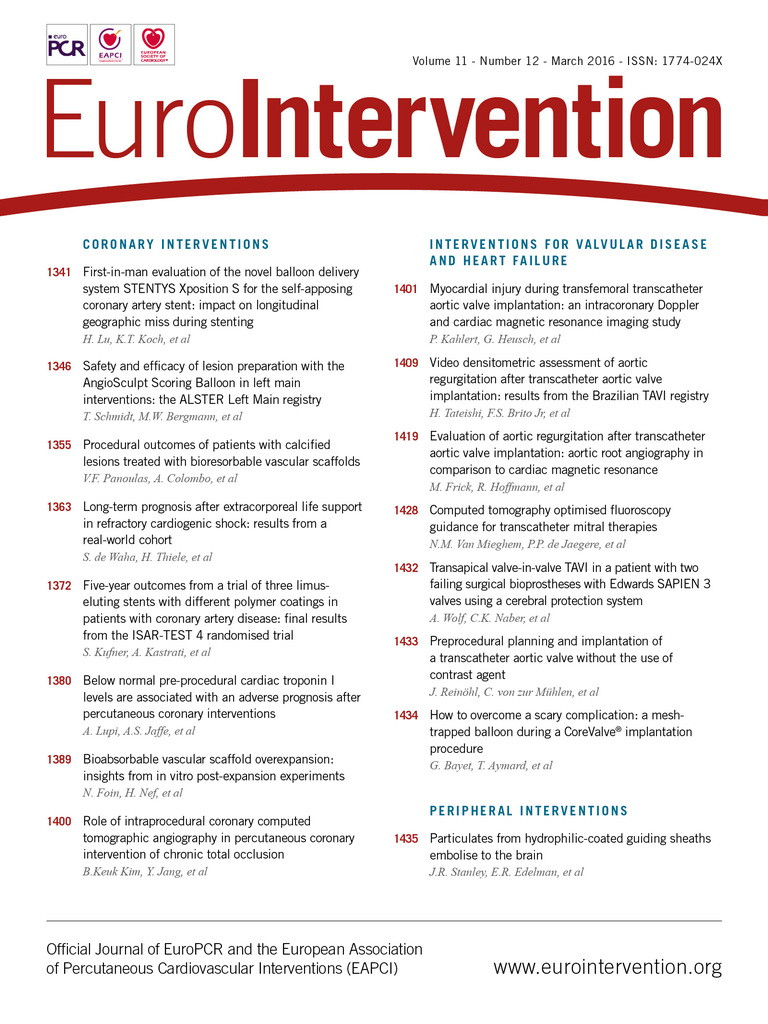

During the first phase of the registry no lesion preparation device was available (historical control). Isolated ostial LAD and ostial LCX stenoses were excluded from the analysis. The remaining patients were divided into three groups according to lesion location and morphology: ostial/proximal, shaft and distal LM stenosis. The ALSTER LM strategy describes the current practice at our centre. Differentiation in the strategy was made for ostial/shaft (Medina 1,0,0), distal stenosis (Medina x,1,0) and distal stenosis with additional ostial side branch lesion (Medina 1,x,1). We adopted the established provisional T-stenting and the mini-crush techniques, adding an ASB lesion preparation manoeuvre up-front. The ASB was the direct default predilatation balloon for dilatation of the single LM (ostial/shaft lesion) or LM/main branch (distal lesion). Kissing balloon was performed as the final step after stenting for bifurcation stenoses. Based on IVUS and OCT data from a subset of patients, no additional post-dilatation or POT seemed to be necessary to achieve complete stent strut apposition and optimal lumen gain. In ostial or shaft stenosis (Medina 1,0,0) patients were treated by lesion preparation with the ASB and following spot stenting only of the LM (Figure 1A). The preferred strategy for distal LM lesions (Medina x,1,0) was predilatation with the ASB including the ostium of the main vessel followed by provisional T-stenting (Figure 1B). The stent was positioned from the LM into the main branch, the side branch was rewired using the main branch coronary wire, and a kissing balloon post-dilatation manoeuvre was performed. For Medina 1,x,1 with the presence of a side branch lesion, the strategy was predilatation with the ASB (into LM/main branch), then side branch dilatation (Figure 1C). Depending on the angiographic result, the side branch was treated with a drug-coated balloon (DCB) followed by provisional T-stenting or a mini-crush was performed, both followed by a final kissing balloon manoeuvre10. We summarised this strategy in Figure 1A-Figure 1C. An IVUS diagnostic test was encouraged by the department policy (in 44.68%) as well as complete revascularisation of any other coronary stenosis (Figure 2).

Figure 1. ALSTER LM strategy. A) for Medina 1,0,0; B) for distal LM lesions; C) for distal LM lesions with ostial side branch lesion.

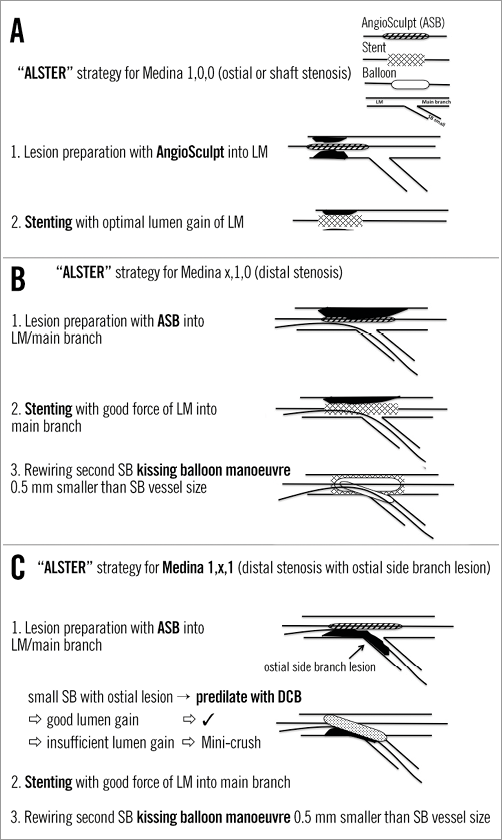

Figure 2. IVUS diagnostic of distal left main stenosis showing heavy calcification.

QUANTITATIVE CORONARY ANALYSIS AND SYNTAX SCORE

Post-interventional quantitative coronary analysis was performed using the Philips Xcelera software (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) with the included clinical application package powered by CAAS 2000 (Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, The Netherlands). The analysis followed a dedicated QCA algorithm with matched projections pre and post intervention. The lumen gain was calculated by subtracting the pre-intervention minimal lumen diameter (MLD) from the final MLD. The percent lumen gain was related to the final MLD. The SYNTAX score was calculated by an experienced interventional cardiologist using the baseline angiogram and the online calculator at www.syntaxscore.com11.

INTRAVASCULAR ULTRASOUND (IVUS) MEASUREMENT

For post-interventional IVUS examination, the Eagle Eye® catheter (Volcano Europe BVBA, Brussels, Belgium) was used. Ultrasound images were recorded starting distal to the bifurcation of the left anterior descending and left circumflex arteries, and covering the entire LM. A validated computer-based contour detection programme (Curad BV, Wijk bij Duurstede, The Netherlands) allowed a semi-automatic detection of lumen, stent and vessel boundaries in longitudinally reconstructed views of the region of interest (Figure 2).

ANGIOSCULPT SCORING BALLOON

The ASB incorporates a flexible nitinol scoring element consisting of three rectangular spiral struts which encircle a semi-compliant balloon. The ASB was designed to optimise percutaneous treatment of complex lesions and to avoid slippage. The ASB “scores” the plaque circumferentially in order to provide maximal lumen gain even in calcified lesions (Figure 3). Clinical studies have shown that the treatment with the ASB in calcified and ostial lesions can be performed successfully12. Using the ASB for predilatation prior to stenting in coronary artery disease has been proven to yield a 30-50% greater lumen gain than either direct stenting or predilatation with a conventional angioplasty balloon catheter12. No data are available so far for the special setting of ULMI.

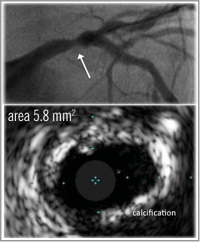

Figure 3. OCT diagnostic of distal left main stenosis showing the effect of the AngioSculpt Scoring Balloon (ASB). A) Distal LM stenosis showing the concurrent OCT image. B) ASB in LM and LAD. C) Result after ASB dilatation and OCT image showing the cutting of the plaque. D) Final result after provisional T-stenting technique and kissing balloon manoeuvre with circular stent expansion.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were described as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). All data were entered into a table and analysed employing the built-in analysis of GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Pre- and post-implantation comparisons were performed using a paired t-test with the SEM. A non-perimetric test was used. Fisher’s exact test was used. For all tests p<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 19.0.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 5.

ENDPOINTS

Endpoints were assessed for MACCE (major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events). MACCE was defined as a composite of all-cause death (cardiac death, vascular death and non-cardiovascular death), cerebrovascular events (CVA/stroke), myocardial infarction (MI) or any repeat vascularisation (target lesion [TLR], target vessel [TVR] or bypass surgery) while standard classifications as defined by the ARC in 2007 were used13.

FOLLOW-UP

Clinical follow-up was performed by telephone interview and/or office visit at six and 12 months.

Results

Seventy ULMI were identified between June 2010 and September 2012 at our centre. Here, we report on 47 patients (mean age 73.1±1.5 years, 85.1 % male) with a low or medium SYNTAX score who received an elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for unprotected LM disease. During the first phase, the ASB was not available, so LM interventions were performed without it (historical control group). After the ASB became available, 34 ULMI were performed following the concept of lesion preparation employing the ASB. In order to be able to perform a meaningful analysis regarding clinical follow-up, twelve patients were excluded due to protected LM interventions, six patients due to emergency PCI, two patients due to isolated ostial LAD and LCX stenosis and three for incomplete documentation of the procedure (Figure 4).

Figure 4. ALSTER Left Main registry patient selection chart.

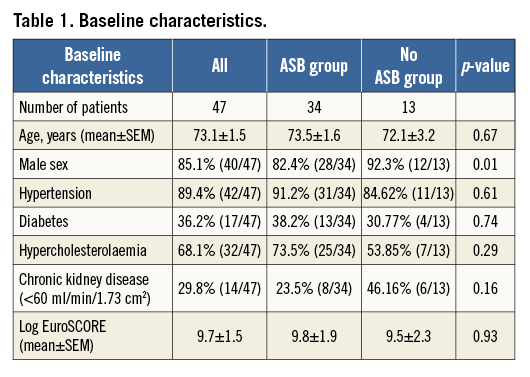

The overall mean log EuroSCORE was 9.7±1.5. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

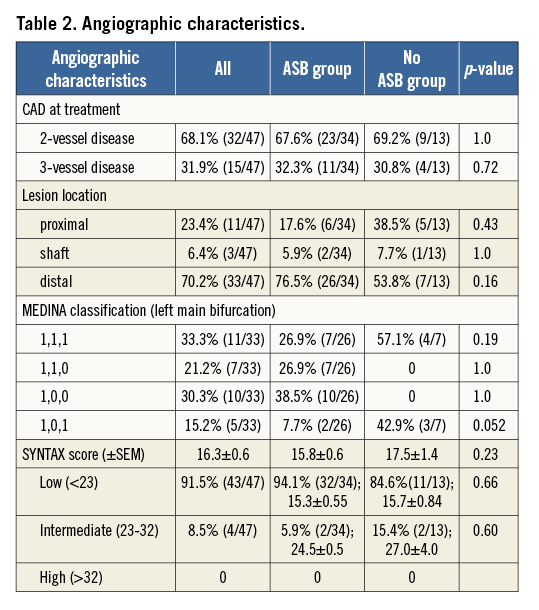

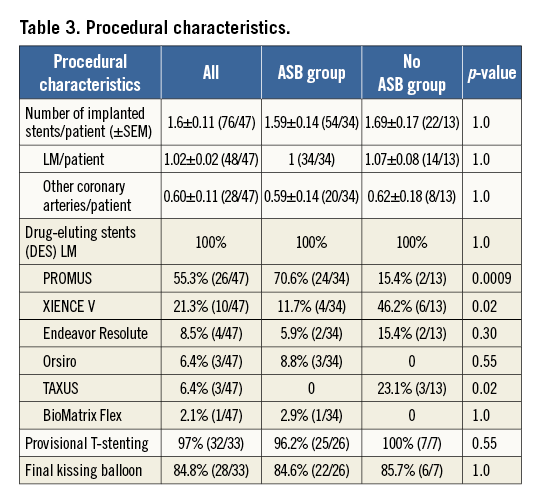

Overall SYNTAX score was 16.3±0.6 (91.5% of patients demonstrated a SYNTAX score below 23 [15.4±0.5], 8.5% of patients had an intermediate SYNTAX score of 23-32 [25.6±1.8]). Both groups were not significantly different for the low and intermediate SYNTAX score (ASB vs. no ASB; low: p=0.6570; intermediate: p=0.5984). No patient had a SYNTAX score >32. Two-vessel coronary artery disease (LM or LM plus additional LAD and/or LCX lesion) was present in 68.1% of the population, while 31.9% had a three-vessel artery disease (LM [plus additional LAD and/or LCX] and RCA lesion). Thirty-three patients (70.2%) had distal LM stenosis, three patients had a shaft stenosis, and 11 patients had an ostial/proximal stenosis (23.4%). Classifying distal LM lesions according to Medina14, 33.3% were 1,1,1, 21.2% were 1,1,0, 30.3% were 1,0,0 and the remaining 15.2% were in Medina class 1,0,1. In 84.8% of the distal LM interventions (28/33), a kissing balloon manoeuvre was performed after stenting. Provisional T-stenting was performed in 97% of distal left main interventions (ASB and historical control group). Only one patient received a mini-crush due to high-grade ostial stenosis of both the main and the side branch. All other patients were treated employing the provisional T technique with only one stent. In case of a significant side branch stenosis, predilatation was performed followed by treatment with a drug-coated balloon (DCB). The LM stent was positioned into the main vessel, either LAD or LCX. If both had equal sizing, the stent was placed in the side branch with the higher graded ostial stenosis. Drug-eluting stents (DES) were used exclusively, mostly (55.3%) PROMUS Element (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). Angiographic and procedural characteristics are summarised in Table 2 and Table 3.

QCA RESULTS

Five patients were removed from the record for the QCA results in the historical control group since CardioPACS (Carestream, Rochester, NY, USA) documentation of the intervention was missing; only a written report of the intervention was available. Lumen gain was numerically higher in the ASB group but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.2636). Overall lumen gain was 1.58±0.10 mm (mean±SEM, 42 patients). In the ASB group (n=34), lumen gain was 1.63±0.12 mm, and in the historical control group (n=8) 1.35±0.12 mm (p=0.2636) (Figure 5A). Percentage lumen gain (lumen gain referred to final MLD) was similar in both groups (ASB vs. historical control group: 53.3±3.0% vs. 48.3±3.8%, respectively; p=0.4388) (Figure 5A). The minimal lumen diameter increased significantly in the ASB group from 1.39 mm to 3.02 mm (p<0.0001) and in the control group from 1.49 mm to 2.84 mm (p<0.0001) (Figure 5B). The mean LM stent diameter was 3.53±0.07 mm (SEM), while the mean reference of the vessel diameter was 3.41±0.09 mm (SEM). The mean LM stent length was 15.21±0.84 mm.

Figure 5. Comparison of lumen gain and gain of minimum lumen diameter for ASB and no ASB. A) Lumen gain (left) as well as percentage lumen gain (right) in the ASB compared to the no ASB group. B) Gain of minimal lumen diameter (MLD) in the ASB (left) and in the no ASB group (right).

IVUS RESULTS

IVUS data were available for 18 patients (52.94%) in the ASB group pre and post intervention as well as for three patients (23.08%) in the control group. The ASB group had a lumen area gain of 3.14±0.33 mm2 and the historical control group had a mean lumen area gain of 2.33±0.88 mm2. Due to the low number of patients in the historical control group a comparison of these two groups is not reasonable.

Periprocedural details

No periprocedural death occurred. All interventions were performed successfully with no appearance of a cardiogenic shock. Peri-interventional mortality ≤30 days was 0%. The ASB was delivered successfully in all cases attempted, partially after predilatation on the lesion with a standard semi-compliant balloon. No distal dissections were observed. No periprocedural or post-interventional complications occurred.

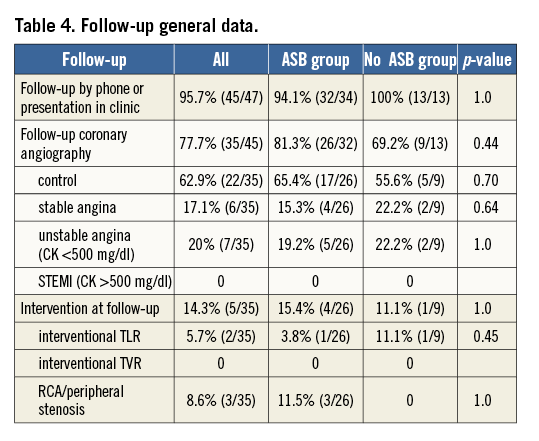

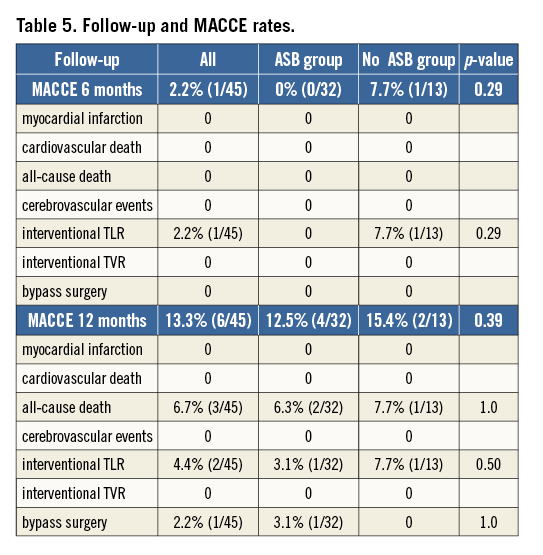

FOLLOW-UP

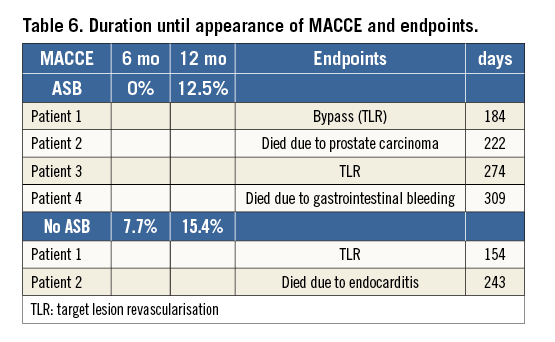

The follow-up rate was 95.6% (45/47) at six and 12 months. Thirty-five patients (77.7%, ASB: 81.3% vs. historical control group 69.2%; p=0.4411) received a coronary angiography in the follow-up period (12 months) with no STEMI or NSTEMI (with CK ≥500 U/l) reported (Table 4). At six months, the overall follow-up MACCE rate was 2.2% with one TLR in the historical control group and 0% MACCE in the ASB group (Table 5). At 12 months, the overall MACCE rate was 13.3% (6/45), mostly driven by all-cause death (3/45; 6.7%). Cardiovascular mortality was 2.2% (1/45) due to endocarditis in one patient in the historical control group. In the ASB group no cardiovascular mortality was seen. At 12 months, the overall repeat revascularisation rate was 6.7% (3/45), with two patients receiving a repeat PCI due to in-stent restenosis including DCB dilatation (target lesion revascularisation). One patient underwent elective bypass surgery due to bifurcation restenosis deemed not feasible for reintervention. Repeat revascularisation was 6.3% (2/32) in the ASB group and 7.7% (1/13; p=1.0) in the historical control group.

At 12 months, two patients in the ASB group still on dual antiplatelet therapy died due to a metastasised prostate cancer and an intestinal haemorrhage with septic peritonitis (2/32, 6.2%). Two other patients needed a repeat revascularisation (6.2%). In the historical control group, one patient died due to endocarditis after a transcatheter aortic valve procedure (1/13, 7.7%), and one TLR (7.7%) was recorded. There is no statistical difference when comparing these two groups in terms of MACCE at 12 months (ASB [4/32, 12.5%] vs. historical control group [2/13, 15.4%]) (Table 5, Table 6). No myocardial infarction, and no cerebrovascular events or TVR were observed.

Discussion

The major findings of this registry are that: 1) lesion preparation with the ASB in ULMI is feasible; 2) lesion preparation with the ASB as the “primary” dilatation is safe in this small series; 3) LM interventions using the concept of lesion preparation with the ASB and provisional T technique result in low TLR and TVR rates at six and 12 months; 4) the concept shows extremely low MACCE rates following PCI of the LM, mainly driven by all-cause mortality with no STEMI or cardiovascular mortality at 12 months of follow-up.

Current data and guidelines give equal recommendations (IB) for both PCI and CABG in patients with unprotected LM stenosis and low or intermediate SYNTAX score. No specific statement is available regarding patients with diabetes, where recent randomised studies favour CABG15. Randomised trials regarding ULMI comparing PCI using new-generation DES with CABG, such as the NOBLE (Nordic-Baltic-British Left Main Revascularization) study or the EXCEL (Evaluation of XIENCE Prime Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery for Effectiveness of Left Main Revascularisation) trial, are expected to clarify further the differential treatment effect of PCI versus CABG for unprotected LM stenosis.

Stenting technique, lesion preparation and lumen gain

Significant unprotected LM stenosis is found in 5 to 7% of patients undergoing coronary angiography1. PCI in these lesions is a challenging procedure, especially in LM bifurcation lesions. Ostial stenosis and shaft stenosis of the LM are known to have a better outcome than distal LM interventions16,17. Different stenting techniques are employed, but the optimal strategy for the different anatomical situations has not yet been established. Recent bifurcation studies omitting ULMI have found less complex approaches with minimal lumen area covered by stent struts to have a good outcome. Stenting of the main vessel followed by balloon angioplasty of the side branch with or without stenting as defined (“provisional T technique”) seems preferable to a two-stent technique due to lower TVR6,7,18. Significantly higher rates of TLR have been reported for two-stent procedures after ULMI19. However, the randomised DKCRUSH-II trial20 demonstrated that a two-stent strategy when optimally performed with FK balloon may reduce the rate of TLR and TVR as well as having favourable clinical long-term results compared to the provisional approach while accepting a higher rate of peri-interventional myocardial infarcts.

Lesion preparation with the ASB prior to stent implantation in the left main setting might allow an optimal stent expansion, which is especially critical for clinical outcome. Following lesion preparation, we used the standard provisional T-stenting technique in 97% of all cases without POT in this registry. There are no existing data employing the concept of “lesion preparation” when performing ULMI. Previous studies have shown that predilatation with the ASB enhances the acute lumen gain with better long-term results than direct stenting or predilatation with a compliant balloon21. In addition, there is a better final lumen dimension, and minimal balloon slippage, and there are low dissection rates after predilatation with the ASB12,22. A numerically greater acute lumen gain was seen in the ASB group, which would support the concept of lesion preparation by ASB in the left main setting. The proximal optimisation technique has been advocated by Foin et al, which was initially tested in a silicone model23. Further studies comparing bifurcation interventions with or without POT are lacking, especially studies of ULMI using POT with hard clinical endpoints. Also, the consensus from the last European Bifurcation Club meeting only advises POT in cases with large differences of the reference diameter, and “to aid difficult recrossing into a SB”, which was performed without any difficulties in our study24. Post-dilatation of the proximal part was performed in these cases by the two balloons employed for the kissing manoeuvre, yet no specific post-dilatation of the LM was performed as is performed in POT23. As demonstrated by IVUS and OCT, optimal adoption of the stent to its natural circular shape was shown in over 50% of our patients (OCT view, Figure 3).

Our QCA data are in line with previous studies. We report a good safety profile, but higher numbers of patients are needed to show possible significantly better acute lumen gain with the ASB. Therefore, our conclusions are limited to the description of this technique being feasible and safe.

Findings from meta-analyses suggest a better clinical and angiographic result when using IVUS guidance25,26. Our IVUS data, collected in >50% (18/32) of the patients in the ASB group and in 23% (3/13) in the historical control group, underline the findings of the QCA.

Final kissing balloon manoeuvre

Final kissing (FK) balloon manoeuvre was performed in 85% of all our distal LM interventions. Non-FK after complex bifurcation stenting is associated with an increased risk for 30-day STEMI10. However, the clinical outcome after FK in distal bifurcation lesions remains undefined. Most data describe higher MACCE rates for ULMI without FK27. We believe optimal stent expansion and good lumen gain as achieved with aggressive lesion preparation as described here should also optimise clinical outcome.

MACCE

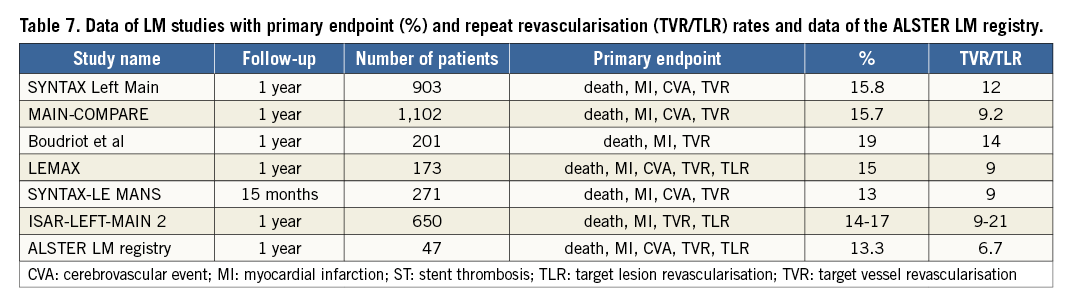

The patient numbers in our registry are low, yet we decided to compare our clinical results to the previously described larger series in order to assess the safety of our new approach of lesion preparation in ULMI. Six and 12-month MACCE rates were low in both groups and are in line with the large randomised studies15,28-31 (Table 6, Table 7). The ASB group had even lower MACCE rates than the historical control group with a 12-month MACCE rate for TLR of 6.7% (TLR and bypass surgery) and 0% for TVR. MACCE rates were mainly driven by all-cause death. Interestingly, there was no TVR, cardiovascular death or myocardial infarction at 12-month follow-up in either group.

Limitations

The conclusions are limited by the registry character with no randomisation; however, the data allow a valid power calculation for a possible randomised trial. The number of patients included is lower than in other studies. All patients come from a single centre with only a few operators. The low number of patients does not allow us to draw conclusions between greater acute lumen gain and better MACCE rates. Also, IVUS guidance was not employed in all patients.

Conclusion

Combining upfront lesion preparation with the AngioSculpt Scoring Balloon with the standard provisional T technique with final kissing balloon for elective, unprotected left main intervention is feasible and safe. This technique, summarised as the ALSTER left main approach, leads to low rates of periprocedural complications and very satisfactory results regarding acute lumen gain. Larger series are needed to show statistically significant improvement of clinical outcome following ULMI with this strategy. Here, we report low MACCE rates for the ASB group driven by all-cause mortality with no STEMI and no cardiovascular death at 12-month follow-up.

| Impact on daily practice Lesion preparation with the AngioSculpt Scoring Balloon followed by the standard provisional T-stenting technique with final kissing balloon in ULMI is not performed yet. This technique is feasible and safe for ULMI and leads to optimal lumen gain following stent implantation. This technique is easy to adopt in daily clinical practice without a higher periprocedural risk. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Biotronik, Berlin, Germany, who distributed the AngioSculpt Scoring Balloons for this registry.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.