Abstract

International guidelines recommend surgical revascularisation for unprotected left main (ULM) coronary artery disease. The introduction of drug-eluting stents (DES) as an emergency therapy has resulted in increasing numbers of patients having stents placed in ULM. As a consequence, important data on the safety and long-term outcome of PCI for ULM have progressively accumulated over recent years, derived mainly from registries rather than prospective randomised trials. These studies indicate that restenosis of the ULM still represents the main predictor of clinical events following stenting. However, the observed incidence is highly variable amongst the published studies and there is little data about the clinical management of restenosis of stents placed in the ULM. In the present paper we review the available literature regarding ULM restenosis, identify its predictors and suggest an algorithm for optimal management.

Introduction

Placement of a stent in an unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis (ULM) is usually well tolerated haemodynamically, and stent implantation should be considered the revascularisation option of choice when patients present with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and acute ULM occlusion. In other less extreme circumstances, concerns about long-term efficacy of stent implantation have resulted in international guidelines continuing to favour coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) rather than percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for ULM1,2. These recommendations are influenced by the reports of clinical outcome of PCI for ULM in the era of bare metal stents, showing variable intermediate results and high rates of restenosis resulting in the need for repeat revascularisation. The introduction of drug-eluting stents (DES) and data from several subsequent studies have suggested increasing equivalence between DES-based PCI and CABG. These data have resulted in the initiation of the Evaluation of XIENCE PRIMETM Everolimus Eluting Stent System (EECSS) or XIENCE V® EECSS Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery for Effectiveness of Left Main Revascularization (EXCEL) trial which is currently recruiting more than 2,000 patients in a randomised trial of DES-based PCI versus CABG with three-year follow-up.

Within clinical practice, increasing numbers of patients are having stents placed in ULM either as an emergency or because they are not suitable for CABG. There is little data about management of restenosis of stents placed in the ULM. The aim of this paper is to review the available literature regarding ULM stent restenosis as well as to describe its incidence, to identify its predictors and to suggest its optimal management.

The issue of sources: registries vs. randomised controlled trials

Several studies have reported the outcome of ULM PCI with DES since their introduction into the market in 2002. Literature in this field is difficult to interpret, as data derived from studies reflects variations in either retrospective or prospective recruitment strategies and also in different periods of clinical surveillance. We performed a systematic search on MEDLINE, Scopus and Cochrane databases from January 2003 to October 2012 using internet-based search engines. The terms used for the search included “left main”, “percutaneous coronary intervention” and “drug-eluting stent”. In the attempt to identify reliable sources of data, for this specific review we have considered only those studies: 1) enrolling at least 100 patients with ULM disease treated by PCI with the use of DES; and 2) with a follow-up of at least six months.

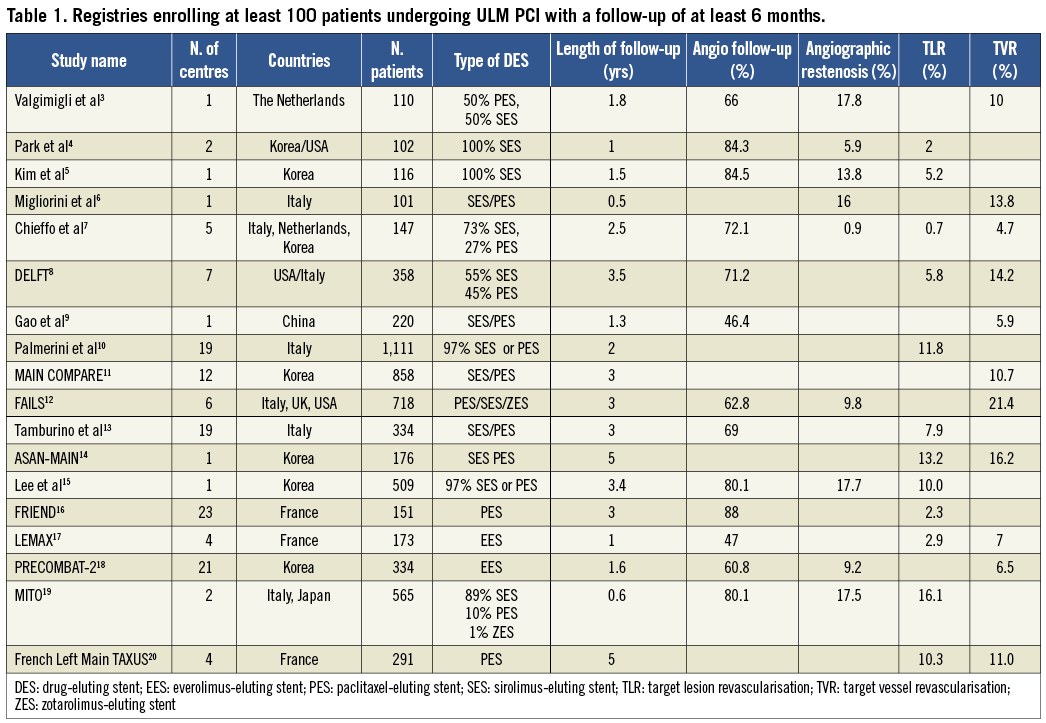

Most of our knowledge regarding long-term performance of ULM PCI with DES comes from registries (Table 1)3-20. Overall, data on more than 6,000 patients are currently available, deriving from both single-centre (n=1,232) and multicentre (n=5,142) registries. A major limitation of this analysis comes from the potential overlap of recruited patients. Most of the data comes from a limited number of centres, thus implying that a substantial proportion of individuals enrolled in single-centre or multicentre registries were also included in multicentre surveys. However, data coming from registries provide crucial insights to understanding the long-term outcome after ULM PCI. Ninety percent of patients have been enrolled in studies published quite recently (after the year 2008) and, since the duration of follow-up has increased progressively over time, for most of them a clinical follow-up of at least three years is available.

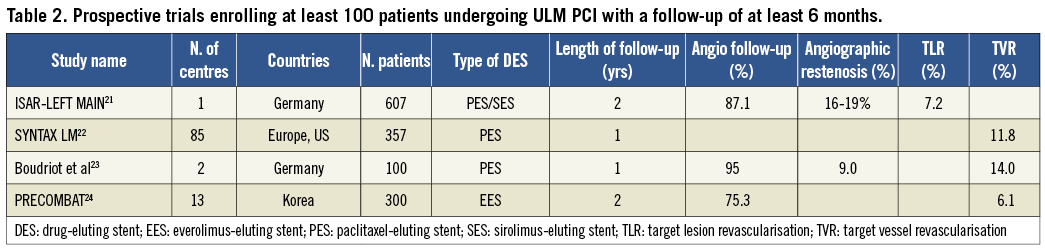

Conversely, to date, only four randomised controlled trials are available (Table 2)21-24. All of these studies are recent, i.e., published after the year 2009, and collectively report the outcome from almost 1,400 patients receiving DES, with a mean follow-up shorter than that of registries. The first three of them were designed for prospective comparison of PCI vs. CABG for the treatment of ULM. Specifically, one represents a subgroup analysis of the multicentre SYNergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery (SYNTAX) study22, one is a bi-centre study23 and one the recently published multicentre Premier of Randomized Comparison of Bypass Surgery versus Angioplasty Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients with Left Main Coronary Artery Disease (PRECOMBAT) trial24. The fourth study is the single-centre ISAR-LEFT MAIN which compares the angiographic and clinical outcome of paclitaxel and sirolimus-eluting stents and provides a clinical follow-up of two years21.

Definition and incidence of ULM restenosis

Angiographic restenosis of ULM is defined as a diameter stenosis of >50% at the target site or the major side branches, such as the left anterior descending artery (LAD) or the circumflex (LCX). Despite the constant use of this definition over time and across all the published studies, the identification of the real incidence of ULM restenosis according to the available literature is challenging. To date, only 10 of 17 registries and two of four prospective trials report its occurrence, which varies widely from 0.9 to 19%.

Differentiating a benign non-functionally significant angiographic lesion from an obstructive ischaemia-inducing functionally significant one is probably more difficult in the ULM bifurcation than anywhere else in the coronary vasculature. Consequently, a simple angiographic assessment has limited relevance without additional data from either carefully performed intravascular ultrasound or fractional flow reserve or non-invasive imaging stress tests to guide interventional decision making. Possibly as a consequence, angiographic ULM restenosis has progressively been replaced by more clinically relevant endpoints, such as target vessel revascularisation (TVR), defined as any repeat revascularisation of the treated vessel including any segments of the LAD or LCX, or target lesion revascularisation (TLR), i.e., any revascularisation performed on the treated segment. Even with these endpoints, the reported TLR and TVR in the published literature demonstrate a wide variability in incidence from 2% to 16.1% and from 4.7% to 21.4%, respectively.

Clinical presentation of ULM restenosis

Most clinicians are anxious about the possibility that ULM stent restenosis will present without warning as sudden death. Review of the available literature does not suggest that this is likely, although there is a lack of truly comprehensive data. In the Failure in Left Main Study (FAILS) registry, approximately one third of patients with angiographic restenosis were completely asymptomatic, one third presented with stable angina and the rest with unstable angina or myocardial infarction12. Conversely, the proportion of patients with unstable presentation was more than 50% in the study of Lee et al, with the remaining patients undergoing revascularisation presenting with silent ischaemia or stable angina15. In the MITO registry, Tagaki reports 12% of patients presented with stable angina and 5% with ACS but the majority of the patients with ULM stent restenosis were detected during routine angiography (70%)19. In this registry, and following further percutaneous treatment for ULM stent restenosis, severe kidney disease and a high EuroSCORE were independent predictors of mortality. Most of the remaining studies usually report the composite incidence of cardiac death, myocardial infarction and stroke as the primary endpoint and, when reported, the rates of ULM restenosis, TLR or TVR are not linked to the modality of clinical presentation. Given these limitations, it is not possible to characterise absolutely how often ULM restenosis causes mortality per se.

Clinical predictors of ULM restenosis

The identification of patients at lower risk of repeat revascularisation would potentially guide the selection of patients who would benefit most from PCI and, on the contrary, identify those for whom CABG is still the option of choice. Additionally, recognising high-risk patients will allow targeting of follow-up rather than routine surveillance for every patient.

CLINICAL AND ANGIOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Among clinical variables, in the study from Lee et al reporting the results of a cohort of 509 patients with an angiographic follow-up of 80% at six to nine months, female gender, the presence of diabetes mellitus and renal failure were identified as independent predictors of restenosis with a univariate analysis, although only female sex remained a significant predictor using the multivariate approach15. The importance of diabetes as a major determinant of restenosis was also confirmed by the French TAXUS Left Main registry20 and the DELFT study8, where the presence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was found to increase the odds of TLR by almost three times at five-year follow-up. However, compared to clinical variables, the characteristics and the location of the target stenosis play an even more important role in predicting ULM restenosis. In the study of Lee et al, the involvement of ULM bifurcation and restenotic pattern were identified as major independent predictors of restenosis at multivariable analysis and patients presenting with bifurcation involvement were more likely to undergo angiographic follow-up. In FAILS, patients initially presenting with a lesion involving the bifurcation represented almost two thirds of patients with angiographic restenosis12 and, similarly, in MITO, restenosis occurred in 8% of patients without bifurcation involvement and in 20% where the bifurcation was involved19. The notable impact of lesion location on angiographic restenosis or the need for revascularisation highlights the low rate of restenosis when bifurcation is not involved. In their multicentre trial including only ULM disease involving the ostium and/or the mid-shaft, therefore not requiring the treatment of the bifurcation, Chieffo et al found that restenosis occurred in less than 1% of cases at more than two-year follow-up7. Reassuring data about distal ULM come from within the SYNTAX-LE MANS study as almost 90% of patients treated with PCI to distal ULM were free of angiographic restenosis at scheduled angiographic follow-up25.

PROCEDURAL CHARACTERISTICS

Amongst procedure-related factors, the available data are consistent in excluding a significant clinical benefit for any particular DES platform when treating ULM. Most data are derived from registries rather than from randomised prospective trials, and relate to paclitaxel (PES) versus sirolimus-eluting stents (SES). However, in the randomised ISAR-LEFT MAIN trial21, 607 patients were prospectively assigned to ULM revascularisation with PES or SES to compare the one-year composite outcome of death, myocardial infarction, and TLR. The study did not show any significant difference for angiographic restenosis in the first year (PES 16.0% vs. SES 19.4%, p=0.30) or TLR (PES 9.2% vs. SES 10.7%, p=0.47) at two-year follow-up. Comparative data in non-ULM lesions have suggested that second-generation everolimus-eluting stents (EES) are associated with superior clinical outcomes, including TVR, compared to non-EES26. The LEMAX (Left Main XIENCE V) study reports the clinical and angiographic efficacy of this second-generation EES17 and, despite a very high rate of involvement of the distal left main (>90%), EES was associated with an encouragingly low rate of both TLR (2.9%) and TVR (7%). The PRECOMBAT-2 study demonstrates similar outcomes in a registry comparison following either EES or a first-generation SES in ULM PCI (MACCE 8.9% vs. 10.8%, respectively)18. The prospective EXCEL trial will test whether EES has comparative outcomes to CABG surgery in patients with ULM.

Conversely, the number of implanted stents and the need for a complex procedure requiring >2 stents in a bifurcation lesion are independent predictors of ULM restenosis16. Consequently, most clinicians now favour a “provisional” single-stent approach, which can be utilised in up to 60% of cases, particularly when the LCX vessel is small and free of disease. In a cohort of 773 patients in a multicentre Italian registry, the one-stent technique was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of two-year major adverse cardiac events27. Of note, this was mainly driven by a significant reduction in TLR, but also by a reduction in cardiac death and myocardial infarction. However, this study is not a true comparison of a single versus a two-stent strategy, as it did not report the proportion of true bifurcations (Medina class 1,1,1), which often necessitate the use of more than one stent. In these cases of “true” Medina 1,1,128 ULM bifurcation with extensive disease in both vessels, a two-stent technique is probably inevitable, and careful and complete lesion preparation, either with non-compliant/cutting balloons or rotational atherectomy, should always be considered. Optimal expansion of the stent at the LCX ostium appears to be a key determinant of clinical outcome18,29.

Follow-up of ULM PCI: clinical or angiographic?

Careful clinical surveillance within the first six months after stent implantation is the usual recommendation with particular emphasis on antiplatelet drug compliance30. Routine coronary angiography was initially suggested by expert consensus, but this has no proven clinical benefit and consequently a clinically-driven symptom-guided management strategy has become an increasingly standard practice for most cases31. As shown in Table 1, most registries report angiographic surveillance in more than 50% of cases, with coronary angiography being scheduled and performed in the first year. Similarly, in prospective trials, angiographic follow-up was often scheduled by protocol, thus reaching rates >80% (Table 2). In the SYNTAX-LEMANS study, angiographic follow-up was mandated at 15 months to preclude the angiogram impacting on the primary endpoint of the study which included the need for repeat revascularisation at one year25.

The type of follow-up, angiographic or clinical, appears modestly to affect the reported rate of restenosis across the studies. For instance, using the same stent (PES) and with a similar proportion of patients undergoing angiographic follow-up (95% and 87%, respectively), TLR at one year varies widely from 9% in the study of Boudriot et al23 to 16.0% in the ISAR-LEFT MAIN21. Similarly, the duration of surveillance can affect the rate of angiographic restenosis or clinically-driven revascularisation. For instance, the rate of TLR in the FRIEND study was 2.3% at two-year follow-up16, while in the study of Palmerini it was 11.8% after three years10.

Coronary computed tomography (CT) has the potential to guide ULM stent follow-up. A number of technical issues, such as the relatively large calibre of stents used, the coaxiality of scan direction with ULM-proximal LAD plane, and the relative protection from motion artefact of this part of the coronary tree, support its use as a valid alternative to repeat coronary angiography. Van Mieghem et al32 have demonstrated that the evaluation of stent patency in the ULM is feasible and that its diagnostic accuracy is very high (98%), including those patients with distal LM bifurcation lesions requiring stenting of only one of the major branch vessels (i.e., the LAD or the CX). However, in patients who required complex bifurcation stenting, i.e., treatment of the LM and both major side branches, the diagnostic accuracy of cardiac CT decreased significantly to 83%.

In the EXCEL trial, routine angiographic follow-up has not been recommended. Recent encouraging data from five-year follow-up of the French Left Main TAXUS registry20 and our review of the existing data support this strategy. Clinicians should emphasise drug compliance, and surveillance with CT or angiography should be reserved for patients with recurrent symptoms or patients with distal bifurcation disease and clinical risk factors for restenosis such as diabetes and/or renal failure.

Mechanisms of ULM restenosis

The left main coronary is a large vessel and is prone to calcification. These specific features mean that ULM stent restenosis can generally be summarised as the consequence of two main mechanisms, either stent underexpansion or marked proliferative neointima formation. It is likely that an element of stent underexpansion is the predominant factor in most cases. From the current literature it is not possible to compare the outcomes of the different bifurcation approaches. However, unless intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is performed, the initial stent may be undersized and stent expansion cannot be predicted by angiographic examination alone. IVUS guidance of left main stent implantation has been shown to impact on three-year outcome33, and recently target values of minimal lumen areas to be achieved following ULM intervention have been suggested. Indeed, among a cohort of 403 patients undergoing post-stenting IVUS and nine-month angiographic follow-up, Kang et al reported that IVUS-assessed stent underexpansion in at least one segment (ostial LAD, ostial LCX, distal ULM before bifurcation and proximal ULM) was associated with an almost five times higher rate of angiographic restenosis compared to patients with appropriate stent expansion, and that post-stenting underexpansion was an independent predictor of MACE29.

Unfortunately, neointima formation is a largely unpredictable event. Cases where an optimally expanded stent in the ULM are obstructed by neointima are likely to be unusual. Importantly, IVUS will detect predisposing factors, such as stent fracture, or identify areas of incomplete lesion coverage with DES. Consequently, although there is some conflicting evidence in the setting of bifurcation lesions generally34, we believe the use of IVUS is mandatory to define the mechanism of restenosis and guide treatment strategies in the ULM.

Management and outcome

Optimisation of medical therapy is unlikely to be the treatment of choice for patients with ULM stent restenosis. Consequently, the choice is either repeat PCI or a switch to surgical revascularisation. Only two retrospective registries have so far reported data on clinical management of ULM restenosis. In the FAILS registry, Sheiban et al reported follow-up data of a cohort of 718 patients receiving DES in six high-volume centres12. Clinical follow-up was available in almost the totality of patients (97.5%) and included repeat angiography in 62.5%, which was clinically driven in a minority of cases (16%). Among 70 patients showing ULM restenosis (9.7%), four were treated with optimisation of medical therapy, seven with CABG and the majority (59 patients) by repeat PCI. Most of these patients presented with a stable clinical condition, thus allowing best clinical management to be discussed appropriately. Overall, the prognosis of 59 patients undergoing repeat PCI was favourable at clinical follow-up to 24 months, revealing a very low rate of cardiac death (one case) or myocardial infarction (two cases), but a rate of TLR in more than 20% of cases. In the Korean registry from Lee et al15 the incidence of ULM restenosis was higher (71 cases in 509 patients, 17.6%) than in the FAILS study. Again, the majority of these patients were treated by PCI (n=40) with the rest receiving CABG (n=10) or optimal medical therapy (n=21). Importantly, MACE-free survival at more than three-year follow-up was not different among the three groups (ranging from 10% to 14.4%), thus probably reflecting the importance of clinical judgement in choosing the best management for each single case. In the MITO registry, multifocal ISR was highly predictive of the need for repeat TLR (67% vs. 35% for focal and 24% for diffuse ISR)19. Treatment with further DES implantation was much more effective in this registry than balloon dilation alone (HR 2.79; 95% CI: 1.23–6.34, p=0.014). There is currently no evidence to recommend drug-eluting balloons in cases of ULM restenosis.

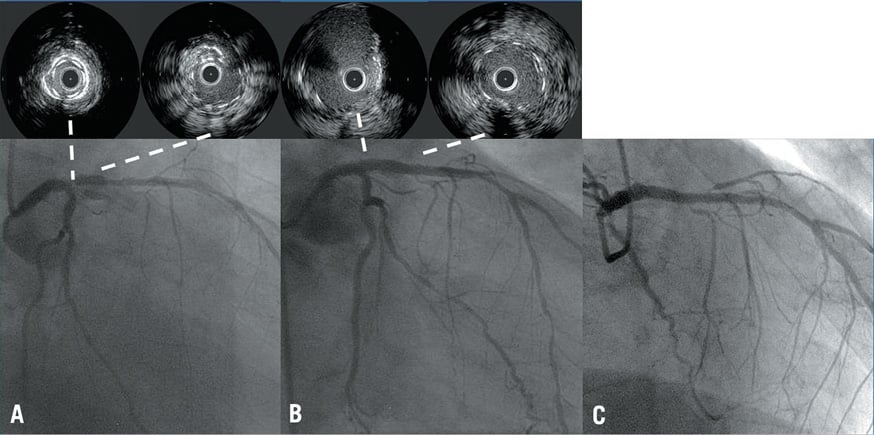

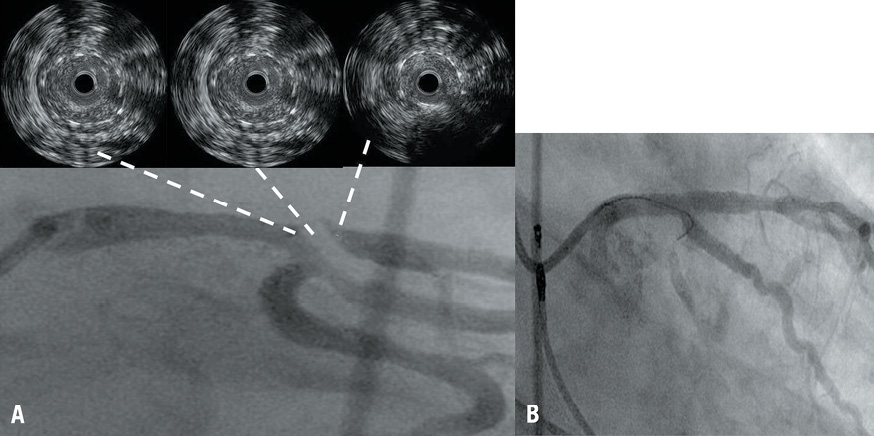

In our experience IVUS should be used to guide and decide the correct management strategy. Indeed, distinguishing the two different predominant mechanisms of restenosis, i.e., neointimal hyperplasia or stent underexpansion is crucial, and the following examples provide illustrations of the clinical issues.

In the first case the patient represented with stable angina eight months after ULM stent implantation. A two-stent strategy was used but intravascular ultrasound was not performed at implant. ULM stent restenosis was evident at diagnostic angiography, and IVUS revealed focal stent underexpansion at the ostium of LAD (Figure 1A). This case was managed with angioplasty with a non-compliant balloon and had a good angiographic result and good stent expansion at final IVUS run with a MLA of 6.7 mm2 (Figure 1B). Follow-up angiogram was available at three years when he represented with symptomatic ostial right coronary artery stenosis (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. A case of ULM restenosis due to stent underexpansion. A) Diagnostic angiography reveals ULM stent restenosis, with IVUS run showing focal stent underexpansion at the ostium of LAD. B) Good angiographic and IVUS result after non-compliant balloon dilation. C) Angiographic follow-up showing good long-term result.

In a comparative illustrative case, a 61-year-old patient (with previous ULM stent using a 4.0×32 mm DES) represented to our clinical attention with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and severe ULM restenosis. An IVUS acquisition from proximal LAD to left main was performed after predilation with a 2.0 mm balloon. It revealed good stent expansion and diffuse in-stent restenosis from proximal LAD to ostial LM (Figure 2A). On the basis of the huge burden of neointima at IVUS imaging, the LCX was wired before stenting and aggressive balloon dilation was undertaken. A second stent (in stent) was deployed resulting in considerable plaque shift, finally leading to the loss of the atrioventricular branch of the LCX (Figure 2B) and a moderate-sized troponin release without clinical consequence.

Figure 2. A case of ULM restenosis due to neointimal proliferation. A) ULM restenosis at ostial LAD localised at the trifurcation with a large intermediate and atrioventricular branch. IVUS run after predilation reveals optimal stent expansion and diffuse in-stent restenosis from proximal LAD to ostial LM. B) Restenosis was managed with stent deployment. However, considerable plaque shift led to loss of atrioventricular branch of LCX.

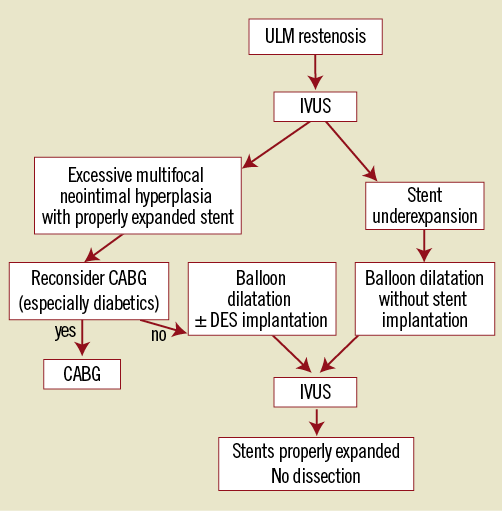

These cases illustrate that IVUS can identify stent underexpansion as the mechanism of restenosis and may allow management with simple balloon angioplasty. Alternatively, diffuse proliferative neointima causing in-stent restenosis should be considered carefully, as there is potential for considerable plaque shift and branch vessel compromise. Figure 3 shows the algorithm we propose for optimal management of ULM restenosis.

Figure 3. Proposed catheter-based management of ULM restenosis.

Conclusions

PCI for ULM is already a valuable option in the emergency management of ULM stenosis. More ULM stents will be placed in patients unsuitable for surgery and further randomised studies, particularly the EXCEL trial, will determine whether elective ULM stenting is comparable with CABG. Even in the era of DES, restenosis remains the “Achilles’ heel” of PCI. Involvement of distal bifurcation, requiring two stents, and the presence of diabetes and/or renal failure are the principal risk factors for restenosis. IVUS guidance at implantation of the stent is crucial to optimise stent expansion and management of in-stent restenosis can be guided by repeat IVUS. ULM stent restenosis can usually be managed by repeat PCI when it is caused by underexpansion of the original stent. Improved implantation technique and enhanced DES technology are likely to improve results of ULM stenting in the future.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Banning has received unrestricted research funding from Boston Scientific and speakers fees from Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular and Medtronic. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.