Introduction

Recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines have extensively investigated antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapy during percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI)1-3. However, based on their complexity and differences from existing ACC/AHA guidelines, it is sometimes difficult to adhere to evidence-driven recommendations for individual decisions. Most recommendations are based on prospective randomised trials, which only partially reflect the “real world” situation. Meta-analyses and guideline-based registries might help to guide daily practice. During invasive cardiovascular interventions combined use of both anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies is mandatory to prevent thrombosis, because activation of both platelets and the coagulation system contribute to thrombus formation. Choice, initiation and duration of antithrombotic strategies are based on the clinical setting (elective, acute or urgent intervention). To optimise the efficacy of therapy and reduce the potential bleeding hazard both ischaemic and bleeding risks have to be evaluated on an individual basis. In 2008, we published a first paper4 aimed at giving practical solutions to handle antithrombotic therapy for patients undergoing PCI in various clinical conditions. Since that time important data from randomised controlled trials and observational studies have been reported leading to a need for an update of these practical recommendations for antithrombotic therapy during PCI.

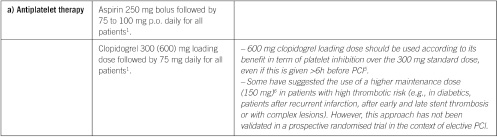

Elective percutaneous coronary intervention

Elective percutaneous coronary intervention (continued)

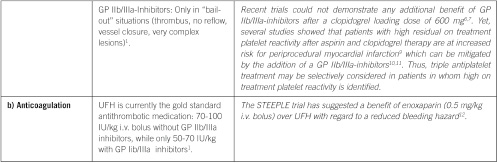

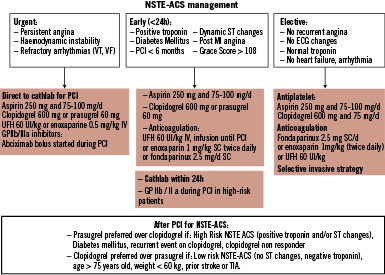

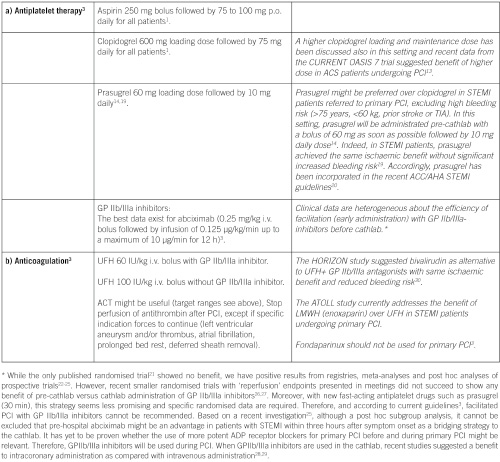

Non ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS)

Pre-cath management for NTSE-ACS patients

1. Patients with very high risk (e.g., persistent angina, haemodynamic instability, refractory arrhythmias), are immediately referred to the cathlab:

– UFH 60 IU/kg i.v. bolus, then infusion until PCI.

– Enoxaparin 0.5 mg/kg IV.

– In patients with high bleeding risk; monotherapy with bivalirudin, 0.1 mg/kg i.v. bolus followed by an infusion of 0.25 mg/kg/hr.

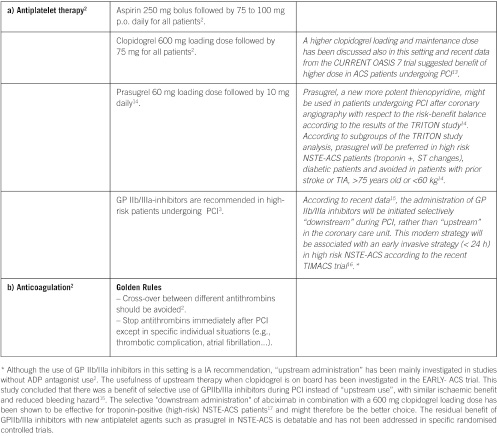

2. In medium to high-risk patients (e.g. troponin-positive, recurrent angina, dynamic ST changes, diabetes, renal dysfunction, LVEF<40%, early post MI angina, PCI < 6 month, prior CABG, intermediate or high GRACE score).

Primarily invasive strategy is planned (<72h), early (< 24h) for high-risk patients:

3. In low-risk patients

Primarily conservative strategy is planned:

Fondaparinux 2.5 mg s.c. daily or enoxaparin 1 mg/kg s.c. twice daily or UFH 60 IU/kg i.v. bolus, then infusion (aPTT-controlled) until PCI.

Management in the cathlab

GOLDEN RULE

Continue the initial therapy! (Don’t switch except after fondaparinux).

If under UFH:

Continue perfusion, ACT measurement might be useful

Target range:

– 200-250 sec with GP IIb/IIIa-inhibitors

– 250-350 sec without GP IIb/IIIa-inhibitors

If under enoxaparin:

within 8h of last s.c. application: no additional bolus

within 8-12h of last s.c. application: add 0.30 mg/kg i.v. bolus

more than 12h of last s.c. application: 0.5 mg/kg i.v. bolus.

Recent data suggested the usefulness of bedside monitoring to tailor anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin during PCI for NSTE-ACS, but effectiveness of these assays has to be validated in prospective randomised trials18.

If under bivalirudin:

An additional i.v. bolus of 0.5 mg/kg and an increase of the infusion to 1.75 mg/kg/hour before PCI is performed.

If under fondaparinux:

UFH 50-100 IU/kg when angiography and PCI is performed.

Figure 1. Management of NSTE-ACS.

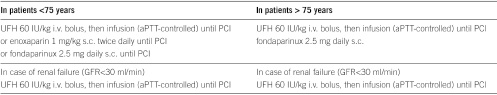

ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

Specific points of interest

Prevention of bleeding during hospitalisation and after discharge

– Assessment of bleeding risk.

– No crossover of antithrombotic therapy (except after initial use of fondaparinux).

– No overdosing of antithrombotic therapy.

– Radial access should be the preferred option in high bleeding risk.

– Stop anticoagulation after PCI unless a specific indication exists.

– Selective downstream use of GP IIb/IIIa-inhibitors in NSTE-ACS seems better than un-selective upstream use.

– Use of PPI in high-risk patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy31.

– Use of low aspirin maintenance dose (< 100 mg)32.

– Monitoring of bleeding risk with platelet function tests has been suggested by recent publications33,34, but remains at this point-in-time a scientific tool and not recommended for routine clinical use.

Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy

– After bare metal stent (BMS) implantation in stable angina:

one month (ASA + clopidogrel).

– After drug eluting stent (DES) implantation (all patients):

one year (ASA + clopidogrel or prasugrel).

– After ACS (all patients independent of therapeutic strategy):

one year (ASA + clopidogrel or prasugrel).

In a recent, large sample size randomised study, the use of dual antiplatelet therapy for a period longer than 12 months in patients who had received drug-eluting stents was not significantly more effective than aspirin monotherapy35. However, this study was underpowered and included low-risk patients without recurrent events within the first year after DES implantation. Larger ongoing randomised controlled trials will address this issue of the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after DES.

Golden rules to avoid premature discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy

– Avoid DES in patients not expected to comply with therapy.

– Avoid DES if surgery is planned within 12 months.

– Avoid DES in patients requiring oral anticoagulation (artificial valve, atrial fibrillation)35.

– Detailed information and education of the patient might prevent premature cessation of antiplatelet therapy.

Most surgical procedures can be performed under dual antiplatelet therapy with an acceptable rate of bleeding: a multidisciplinary approach is required (cardiologist, anaesthesiologist, surgeon).

In surgical procedures with high bleeding risk:

– Stop clopidogrel five days or prasugrel seven days before surgery and stay on ASA, unless very high bleeding risk surgery.

– The substitution of combined antiplatelet therapy with LMWH is ineffective and useless.

– Restart clopidogrel as soon as possible with loading dose: 300 to 600 mg according to both bleeding and ischaemic risk.

– In very high risk patients (e.g., multivessel DES <1 years, left main stenting...), in whom the cessation of antiplatelet therapy before surgery seems to be dangerous, it has been suggested to switch from clopidogrel five days before surgery to a short half-life antiplatelet agent, e.g., the GP IIb/IIIa-inhibitors tirofiban or eptifibatide and stop infusion of these agents four hours before surgery. Although these protocols are attractive and have been successfully used in small patient series, there is currently no controlled evidence to support their use37,38.

Patient under chronic anticoagulation

To avoid long-term triple antithrombotic therapy, BMS implantation or the use of pure balloon dilatation is preferred over the use of DES36. In patients receiving chronic anticoagulation, the uninterrupted strategy will be preferred in order to avoid bridging therapy with heparin associated with increased ischaemic and bleeding risk36. In these patients, radial should be the first choice to lower bleeding complications36.

Antiplatelet therapy monitoring

– No consensual test system available.

– No consensual definition of “non” – or “low” – response.

– No large clinical evidence that tailored antiplatelet therapy improves clinical outcomes.

– Monitoring of antiplatelet response by platelet function assays is used at present only in clinical research. Small sample size studies have suggested benefit of tailored antiplatelet therapy10,11. However, data are not strong enough to support the common use of the available assay systems in daily clinical practice. Results from the ongoing studies of personalised P2Y12 inhibitor therapy such as GRAVITAS or ARCTIC will address the issue of the relevance of tailored antiplatelet therapy.

Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

In patients with a history of HIT, neither UFH nor LMWH should be used (cross reactivity). Bivalirudin is the best option in this case for elective PCI and ACS. Others options are argatroban, lepirudin and danaparoid.