Abstract

Thrombotic and bleeding risks differ between sexes, partly in relation to distinct biology and hormonal status, but also due to differences in age, comorbidities, and body size at presentation. Women experience frequent fluctuations of prothrombotic and bleeding status related to menstrual cycle, use of oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, or menopause. Although clinical studies tend to underrepresent women, available data consistently support sex-specific differences in the baseline thrombotic and haemorrhagic risks. Compared with men, women feature an increased risk of in-hospital bleeding related to invasive procedures, as well as long-term out-of-hospital bleeding events. In addition, the inappropriate dosing of antithrombotic drugs, which is not adapted to body weight or renal function, is more frequently associated with an increased risk of bleeding in women compared to men. While acute coronary syndrome (ACS) studies support similar antithrombotic drug efficacy, irrespective of sex, women may receive delayed treatment due to bias in their referral, diagnosis, and invasive treatment decisions. The current clinical consensus statement highlights the need for an increased awareness of sex-specific risks and biases in ACS management, with a focus on sex-specific bleeding mitigation strategies, antithrombotic management in special conditions (e.g., myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries), and barriers to female representation in cardiovascular trials. This manuscript aims to provide expert opinion, based on the best available evidence, and consensus statements on optimising antithrombotic therapy according to sex, which is critical to improve sex-based disparities in outcome.

Sex-based differences in the pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, therapy, and outcome of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are well described1234. Although sex-based disparities in the invasive management of patients with ACS and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have narrowed in recent years, clinical outcomes after ACS remain worse for female compared to male patients5. Data consistently show that female patients experience greater delays in the diagnosis and treatment of ACS compared to male patients, these being associated with the consequent late administration of antithrombotic agents during ongoing cardiac ischaemia6. Although there is a sex-based bias in referral by both healthcare practitioners and patients7, differences in coronary anatomy and function, peripheral vascular anatomy and comorbidities, psychosocial factors, and vascular and neural stress responses may contribute to the observed differences in the safety and efficacy of antithrombotic drugs between sexes89. As women are often underrepresented in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of antithrombotic treatment, new data and adequately powered trials in women are required to identify independent associations between sex and the efficacy/safety of antithrombotic treatment. Considering these unique challenges to optimising antithrombotic treatment based on sex, the aim of the current consensus statement, led by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Thrombosis, is to provide consensus-based guidance, founded on the best available evidence and expert opinion.

Sex and antithrombotic therapies

Baseline differences between sexes in the coagulation system

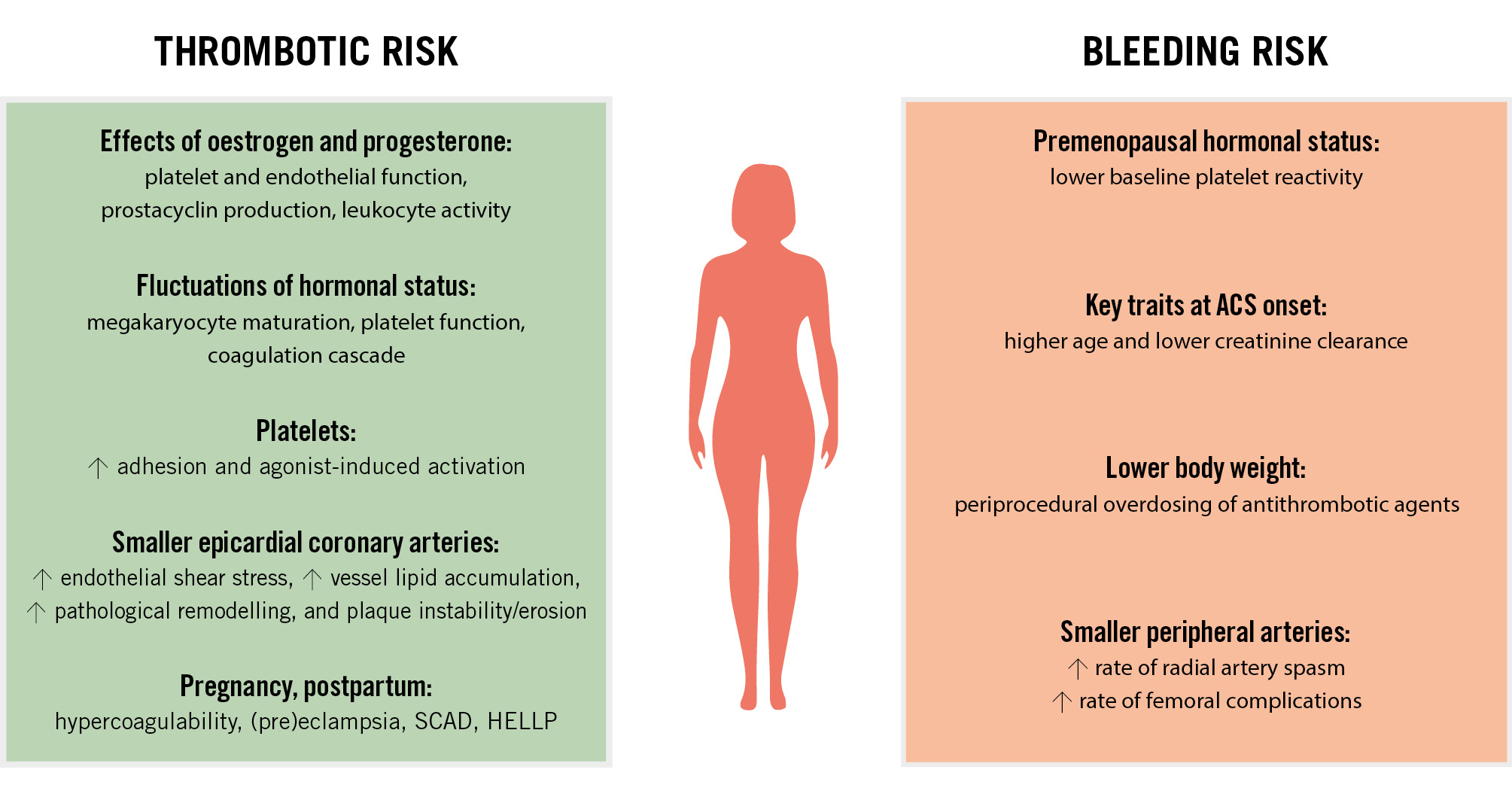

The risk of coronary thrombosis differs between females and males. This is especially true before the menopause due to oestrogen and progesterone fluctuations influencing blood platelets and procoagulant factors1011. Oestrogen promotes prostacyclin production, improves nitric oxide availability, and reduces platelet aggregation, which might be protective against the premature onset of coronary artery disease11. Fluctuations in hormonal status associated with menstrual cycles, oral contraceptive use, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy all influence thrombotic and bleeding risks61213 (Supplementary Appendix 1). Of note, lower platelet reactivity in premenopausal women has been related to the presence of oestrogen receptors on the platelet surface14. Some reports have also indicated more pronounced platelet adhesion to injured vessels in males15, but greater agonist-induced platelet activation and aggregation in females11161718 (Figure 1). There are also differences in protease-activated receptor (PAR) signalling pathways between sexes, with platelet PAR1 signalling shown to be reduced in women and increased in men during myocardial infarction (MI)19. Increased endothelial shear stress, which is associated with significantly smaller epicardial coronary arteries in females, may influence vascular lipid accumulation, pathological remodelling, and plaque instability. This contributes to distinct coronary atherosclerosis characteristics, including a more diffuse and non-obstructive pattern, reduced overall plaque burden and calcification, and fewer signs of necrosis in the plaque core20 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Factors associated with thrombotic and bleeding risks in women. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; HELLP: haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets; SCAD: spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Thrombotic/ischaemic risk according to sex in patients treated with antithrombotic agents

The major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) rate after ACS is higher in female than male patients, which might be due to sex-based disparities in clinical characteristics and treatment621. Women tend to present with ACS at an older age and with a higher burden of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease, compared to men1. The available evidence shows a similar efficacy of antithrombotic agents for ACS/PCI in both sexes. In the Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration meta-analysis, there was no interaction between sex and the efficacy of aspirin versus placebo for secondary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention22. As far as dual antiplatelet (DAPT) therapy is concerned, a meta-analysis comparing clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone in patients presenting with ACS and/or undergoing PCI showed that the absolute risk of MACE was higher in women than in men, and the relative benefit of clopidogrel therapy appeared attenuated in women versus men (7% vs 16% reduction)23. In the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON-TIMI 38 trial), which evaluated prasugrel versus clopidogrel on top of aspirin therapy in ACS patients undergoing PCI, there was no significant interaction between the efficacy of prasugrel and sex, but the magnitude of the effect was greater in men at 15-month follow-up24 (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, in the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, which compared ticagrelor to clopidogrel in aspirin-treated patients with ACS, no significant sex-related difference was found for MACE reduction at 1 year (Supplementary Table 2)25. Similar results were observed in the The Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 5 (ISAR-REACT 5) trial (Supplementary Table 3)26.

Some interest over the combination of antiplatelet therapy and direct oral anticoagulants has emerged. In the Anti-Xa Therapy to Lower cardiovascular events in addition to Aspirin with or without thienopyridine therapy in Subjects with Acute Coronary Syndrome 2–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 51 (ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51) trial, rivaroxaban (2.5 mg or 5 mg twice daily) added to aspirin plus clopidogrel reduced the risks of MACE across both sexes27.

In ACS/PCI patients with an indication for oral anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, no significant interaction between sex and major efficacy outcomes was observed (Supplementary Table 4).

Clinical consensus statements: antithrombotic agents

There is no significant sex-related difference in the efficacy of antithrombotic drugs for secondary CVD prevention.

Delays in ACS diagnosis and invasive treatment should be addressed to enable timely initiation of treatment with antithrombotic drugs.

Bleeding risk according to sex in patients treated with antithrombotic agents

Although primary analyses of pivotal trials on antithrombotic therapies in ACS do not indicate an interaction between sex and bleeding outcomes (Supplementary Table 1-Supplementary Table 2-Supplementary Table 3-Supplementary Table 4), there is a wealth of additional data from multivariate analyses of dedicated substudies demonstrating a higher risk of bleeding and vascular complications in females versus males, especially when femoral access for PCI is used6102829. Female ACS patients tend to be older, with more comorbidities when compared to their male counterparts30. In this context, it should be noted that female ACS patients may receive higher antithrombotic drug doses than appropriate for their body weight or renal function31.

The ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes advocate an early invasive approach and use of weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin (UFH) as the first-line anticoagulant agent for most patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS)32. In patients undergoing coronary angiography (CAG) outside of the recommended time window, antithrombotic “bridging” with fondaparinux prior to angiography was associated with significantly fewer Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 3-5 (adjusted [adj.] hazard ratio [HR] 0.21) and access site-related bleeding events (adj. HR 0.49) compared to enoxaparin in a contemporary patient population33 and in pivotal fondaparinux trials3435. In the Fifth Organization to Assess Strategies in Acute Ischemic Syndromes (OASIS-5) trial, fondaparinux substantially reduced the occurrence of major bleeding events and access site-related bleeding in both sexes compared to enoxaparin, but the magnitude of the effect on bleeding risk reduction was greater in women than in men (HR 0.45 vs 0.60, respectively)3435.

The age-dependent risk of bleeding is even more pronounced in premenopausal women, being 4-fold higher for Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major/minor bleeding events in females younger than 50 years of age, compared to males in the same age category36. This increased bleeding risk in young females might be partly related to the differential effects of sex hormones on platelet activity, with lower baseline platelet activity in the presence of platelet oestrogen receptors in premenopausal females1614. Additionally, young patients, regardless of sex, tend to be treated with excessive doses of anticoagulants in the setting of ACS and PCI; still, this excess dosing is associated with significantly higher bleeding rates in young females than in young males37. Importantly, women presenting with cardiogenic shock had a higher risk of major bleeding events compared to men (adj. odds ratio [OR] 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.12-1.34)38.

Beyond non-modifiable factors such as age, creatinine clearance, and other comorbidities, the modifiable factor of arterial access selection also differs between sexes; femoral access was more frequently used (5-50%) in females than in males in the majority of studies and accounts for almost half of bleeding events36394041. An effort should be made regarding the proper training and awareness of interventional cardiologists in strategies such as ultrasound-guided access, smaller sheath sizes, and earlier sheath removal in order to mitigate the bleeding events associated with vascular puncture4142. Radial access remains an effective method to reduce access site bleeding complications43. Various prevention approaches, including medications like vasodilators and calcium channel blockers, aim to reduce radial artery spasm44. Equipment-related prevention includes the use of hydrophilic tools, special 6-in-5 Fr sheaths, minimising catheter exchanges, and avoiding cold intra-arterial injections45.

Consensus statements: mitigation of bleeding risks

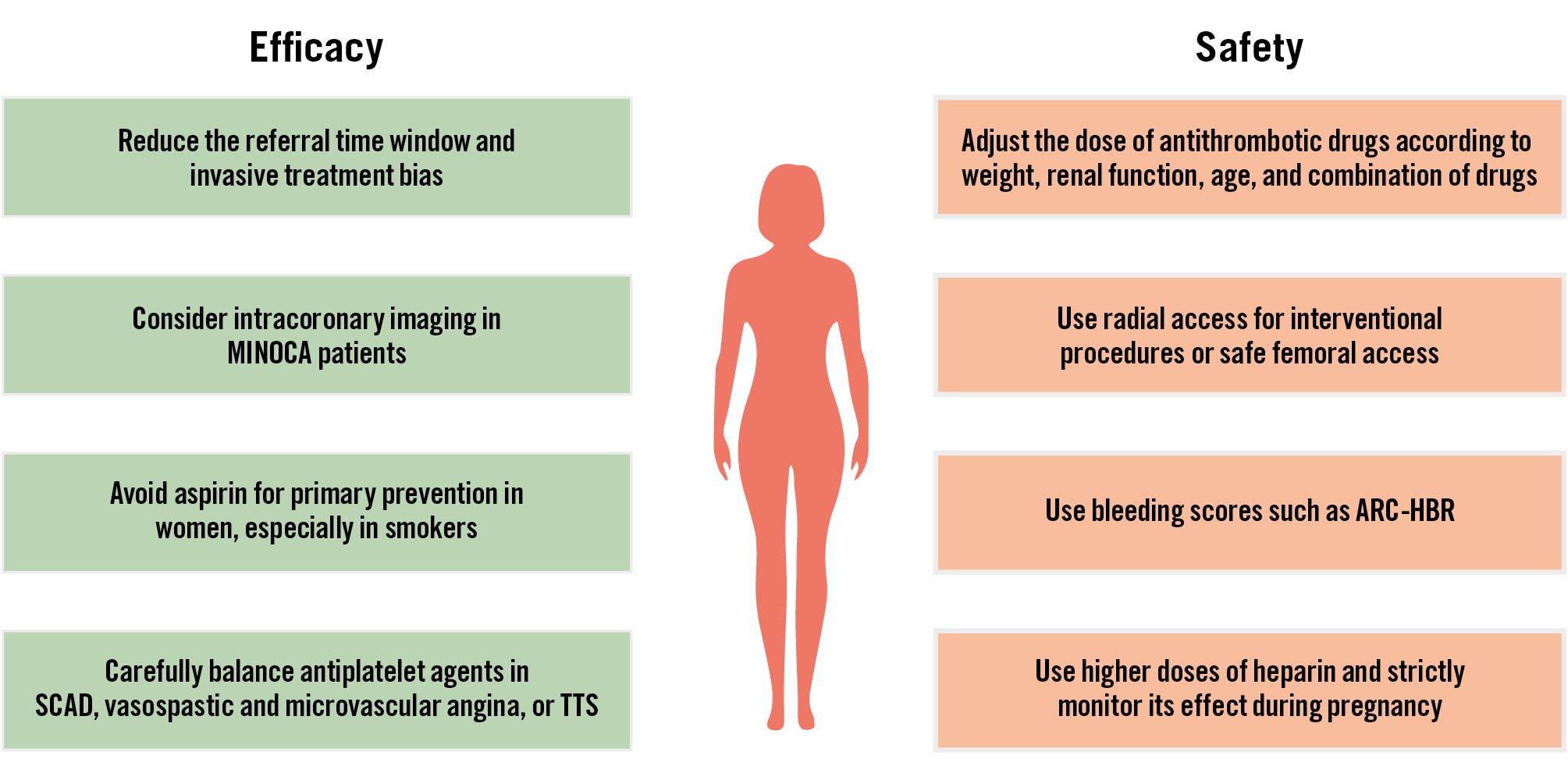

Strategies aiming to mitigate the bleeding risks associated with the femoral access site are advisable (Figure 2):

• Favour radial access over femoral access, with emphasis on spasm prophylaxis and the use of dedicated radial equipment.

• Utilise ultrasound-assisted puncture when femoral artery access is needed.

Avoid excess dosing of periprocedural anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents (Figure 2):

• Body weight and/or renal function-adjusted dosing of periprocedural antiplatelet agents (the P2Y12 inhibitor cangrelor or the glycoprotein [GP] IIb/IIIa inhibitors tirofiban or eptifibatide) and anticoagulants (UFH, low-molecular-weight heparins [LMWH], bivalirudin) should be used. When a combination of UFH and GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors is applied, it is advisable to reduce the dose of UFH from 70-100 U/kg to 50-70 U/kg and to monitor its effect using activated clotting time testing.

• For NSTE-ACS patients without an immediate invasive strategy, anticoagulants with a favourable safety profile are preferable. It is advisable to select fondaparinux over enoxaparin.

Long-term selection of antithrombotic treatment type or duration after ACS/PCI should be based on patient comorbidities rather than sex, recognising the higher comorbidity burden in women compared to men (Figure 2).

Use of guideline-endorsed bleeding scores (such as Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk [ARC-HBR] and PRECISE-DAPT4647) is advisable (Table 1).

Figure 2. Strategies to improve the efficacy and safety of antithrombotic agents in women. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ARC-HBR: Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk; MINOCA: myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries; SCAD: spontaneous coronary artery dissection; TTS: Takotsubo syndrome

Table 1. Ischaemic and bleeding risk scores for the secondary prevention of events following ACS and PCI, and the role of sex.

| Risk scores# | C-statistic | Predictors | Role of sex and/or strongest (significant) predictor |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRACE (I)* | 0.7 | Systolic blood pressure, age, Killip class, heart rate, cardiac arrest, serum creatinine levels, ST-segment deviation, cardiac biomarker increase | No interaction between sexes for primary endpoints |

| CRUSADE (B)# | 0.6-0.8 | Female sex, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, congestive heart failure, haematocrit level, creatinine clearance | HR female sex 1.31 (95% CI: 1.23-1.39) |

| GRACE+CRUSADE (I+B) | n.a. | See above | OR cardiac death/bleeding:female: 27.42 (95% CI: 21.64-34.74)male: 34.80 (95% CI: 28.89-41.91) |

| PARIS CTE (I) | 0.7 | Diabetes, ACS, smoking, creatinine clearance, prior PCI or CABG | No sex strata |

| PARIS MB (B) | 0.7 | Age, BMI, smoking, anaemia, creatinine clearance, triple therapy | No sex strata |

| DAPT (I+B)* | 0.6-0.7 | Myocardial infarction, PCI, diabetes, stent diameter <3 mm, smoking, paclitaxel stent, heart failure or low ejection fraction, vein graft intervention, age | No sex strata |

| CHA2DS2-VASc (I)# | 0.6 | Female sex, age, heart failure, hypertension, CVA, venous embolism, vascular disease, diabetes | OR female sex 2.53 (95% CI: 1.08-5.92) |

| ACUITY (B)# | 0.7 | Female sex, age, creatinine, white blood cell count, anaemia, ST-segment elevation | OR female sex 2.32 (95% CI: 1.98-2.72) |

| HAS-BLED (B) | 0.7 | Hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, stroke, prior bleeding, labile INR, alcohol or drug use, predisposition to bleeding (e.g., medication) | No sex strata |

| PRECISE-DAPT (B)* | 0.7 | Age, creatinine clearance, haemoglobin levels, white blood cell count, previous spontaneous bleeding | No sex strata |

| #Taking female sex into account. *Recommended by (ESC) guidelines; C-statistic for risk prediction. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; B: bleeding risk score; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CI: confidence interval; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; HR: hazard ratio; I: ischaemic risk score; INR: international normalised ratio; n.a.: not applicable; OR: odds ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention | |||

Antithrombotic agents in the settings of MINOCA

Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA)48 is classified into epicardial and microvascular disease. In the absence of critical coronary stenoses, the main pathological findings are plaque rupture or erosion, epicardial or microvascular spasm, thromboembolism, or spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD)49. Data are scarce regarding which antithrombotic drug should be used for the treatment of MINOCA, and underlying pathologies should be addressed.

Plaque erosion

In the small EROSION trial (n=60; <15% women), patients with ACS and plaque erosion were treated with antithrombotic therapies (aspirin, ticagrelor, UFH) without PCI and had favourable 1-year outcomes50. In the EROSION III trial in ST-segment elevation MI patients with early infarct artery patency (n=226; 20% women), optical coherence tomography [OCT]-based diagnosis and conservative treatment with antithrombotic therapies (aspirin, ticagrelor, UFH) resulted in comparable MACE rates in both the conservative and PCI-treated arms51.

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection

The majority of SCAD patients are female and undergo conservative management. However, for these patients, there is a lack of consensus regarding the utilisation and duration of either aspirin alone or DAPT. A small study of patients on DAPT who underwent repeat angiography showed dissection healing in nearly all cases of SCAD52. Conversely, a small registry of conservatively managed SCAD patients showed that, at 1 year, patients on DAPT had a higher MACE rate than those on single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT)53.

Vasospasm

Vasomotor dysfunction (both epicardial and microvascular) is more common in women, with vasoreactivity induced by lower doses of acetylcholine compared to men54. Data to support the use of aspirin in patients with vasospasm are lacking. High-dose aspirin (>325 mg daily) inhibits prostacyclin production, and can aggravate vasospasm55. Low-dose aspirin (<100 mg) can inhibit thromboxane A2 (TXA2), which is implicated in spasm, but clinical results are conflicting, with some studies showing that low-dose aspirin was also associated with frequent coronary spasm56.

Takotsubo syndrome

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is more common in women than in men. Despite aspirin use, women with TTS have been shown to have impaired endothelial function with excess TXA2 formation and enhanced platelet reactivity57. In the international Takotsubo registry, aspirin use was not associated with a lower risk of major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events at 30 days or 5 years58. A subsequent meta-analysis also indicated a higher incidence of cardiovascular events with long-term antiplatelet therapy59.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction

The hallmark of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) is enhanced coronary vasoconstriction, and it is much more common in women. TXA2 leads to arterial constriction, platelet aggregation, and vascular injury, while aspirin reduced endothelial platelet adhesion and conferred microvascular protection in mice60. Whilst unsupported by evidence, low-dose aspirin could be useful in CMD by reducing platelet-rich microembolism and downstream events, if confirmed in clinical studies.

Consensus statements: antithrombotics in MINOCA PATIENTS

Intravascular imaging is advised to confirm plaque erosion in MINOCA patients who may benefit from a conservative approach consisting of DAPT (potent P2Y12 inhibitor and aspirin) for 12 months without undergoing PCI.

In the overall MINOCA population, the choice to treat patients with either DAPT or only aspirin should be based on underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, irrespective of sex.

In patients with conservatively managed SCAD, vasospastic and microvascular angina, or Takotsubo syndrome, the adoption of DAPT is not advisable based on current available data.

Underrepresentation of women in RCTs investigating antithrombotic therapies

Participation-to-prevalence ratio and screening failures in RCTs of chronic and acute coronary syndromes

Despite the call from regulatory bodies for equal representation, women remain underrepresented in clinical trials, especially in CVD studies, with inclusion rates varying greatly based on disease type6162636465 (Table 2). The participation-to-prevalence ratio (PPR; the percentage of women among trial participants/percentage of women among disease population) has been used to establish female representation in clinical trials relative to their prevalence in the diseased population66. After accounting for age and sex-specific disease prevalence, a substantial underrepresentation of women (PPR <0.6) was found for trials in the chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) and ACS domains, and the representation of women was particularly low in studies where the average participants’ age was between 61 and 65 years6667. Of note, the PPR strictly depends on disease type and epidemiological data quality, with a potential misalignment between clinical trials and population-based data66. Another suggested driver for the unbalanced representation of women was the selection of sex-biased inclusion criteria. A recent analysis of clinical trials supporting U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of cardiovascular drugs, focusing on the percentages of screening failure in both sexes, has shown that only one ACS trial reported a higher percentage of screened-out women as compared to men (32% vs 23%, respectively), hence a lower enrolment of women could not be completely ascribed to this phenomenon66. Female patients are better represented in the transcatheter treatment of severe aortic stenosis compared to the coronary field, particularly in early landmark trials5. Evidence suggests that women may derive greater benefit from transfemoral aortic valve implantation than from surgical treatment. However, the PPR remains consistently around 0.7368.

Table 2. Sex-specific analysis of the most relevant RCTs on antiplatelet therapies.

| INFUSE-AMI | PLATO | CHAMPION PHOENIX | TROPICAL-ACS | GLOBAL LEADERS | ISAR-REACT 5 | MASTER DAPT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year ofpublication | 2014 | 2014 | 2016 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2023 |

| NCT number | NCT00976521 | NCT00391872 | NCT01156571 | NCT01959451 | NCT01813435 | NCT01944800 | NCT03023020 |

| Study design | Multicentre, open-label, controlled, single-blind, randomised2x2 factorial trial | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial | Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy trial | Multicentre, randomised, parallel-group, open-label, assessor-blinded trial | Multicentre, randomised, open-label trial | Multicentre, randomised, open-label trial | Multicentre, randomised, open-label trial |

| Population | 452 anterior STEMI patients | 18,624 ACS patients | 11,145 patients undergoing elective or urgent PCI | 2,610 ACS patients | 15,968 all-comers patients | 4,018 ACS patients planned for invasive strategy | 4,579 HBR patients randomised at 1 month after PCI to abbreviated or standard DAPT |

| Female | 26% | 28% | 28% | 21% | 23% | 24% | 30.7% |

| Antiplatelet therapy | Abciximab vs placeboThrombectomy vs placebo | Loading dose of ticagrelor vs loading dose of clopidogrel within 24 h of the most recent cardiac ischaemic symptoms and before any planned or urgent PCI | Cangrelor (I.V. bolus then infusion) vs clopidogrel before PCI | Guided de-escalation from prasugrel to clopidogrel or standard DAPT therapy | Experimental DAPT (1 month followed by23 months of ticagrelor monotherapy) vs reference strategy(12 months of DAPT followed by12 months of aspirin monotherapy) | Loading dose of ticagrelor as soon as possible after randomisation vs prasugrel loading dose once coronary anatomy was known | Abbreviated (immediate DAPT discontinuation, followed by single APT for ≥ 6 months) or standard regimen (DAPT for ≥ 2 additional months, followed by single APT for11 months) |

| Results | Higher rate of MACE in women (30 days)No difference in infarct size (30 days) (p for interaction=0.71) | Female sex was not an independent risk factor for adverse clinical outcomes in moderate-to-high risk ACS patients at 1 year (p for interaction=0.78) | Cangrelor reduced the odds of the primary endpoint by 35% in women and by 14% in men compared with clopidogrel at48 hours (p for interaction=0.23) | The 1-year incidence of the primary endpoint did not differ in guided de-escalation vs control group patients (p for interaction=0.60) | Similar risk of the primary endpoint at2 years (p for interaction=0.63)Higher risk of BARC 3 or 5 bleeding and haemorrhagic stroke in women at2 years (p for interaction=0.09) | No significant interaction between sex and study drug effect (p for interaction=0.275)The superior efficacy of prasugrel was more evident in men | Abbreviated DAPT was associated with comparable NACE rates in men and women (p for interaction=0.65)There was evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effect by sex for MACCE, with a trend towards benefit in women (p for interaction=0.04) |

| ACS: acute coronary syndrome; APT: antiplatelet therapy; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; HBR: high bleeding risk; I.V.: intravenous; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; NACE: net adverse clinical events; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | |||||||

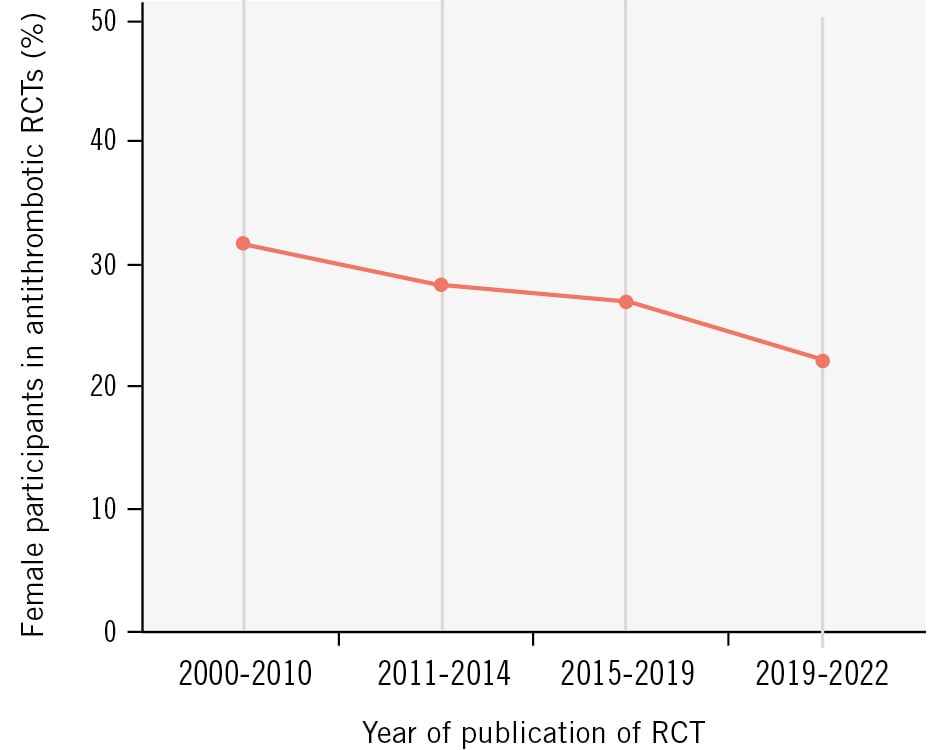

Participation of women in RCTs on antithrombotic therapy and sex reporting

We conducted a systematic review of all RCTs on antithrombotic therapies with the goal of determining temporal trends in female enrolment and patterns of sex reporting. There were 29,398 interventional clinical trials on cardiovascular disease registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2021 with reported results. Search strategy criteria and details of the trials are displayed in Supplementary Table 5-Supplementary Table 6-Supplementary Table 7. Of those, 1,156 were selected based on the following search criteria: ACS, CCS, PCI, atherosclerosis, antiplatelet, antithrombotic, aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitor, prasugrel, ticagrelor, clopidogrel, and cangrelor. After excluding duplicates, phase I and II RCTs, and those with a sample size <500 patients, there remained 64 studies with a publication year between 2001 and 2021, and these were included in the final analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). The overall female representation was 26.6%, with a decreasing enrolment rate per year of publication over the analysed period (Figure 3). Sex-specific analyses of the primary outcome were reported in 42 clinical trials (65.6%). Importantly, only 8 trials (12.5%) reported sex-specific baseline characteristics. In this analysis, women were significantly older than men (mean±standard deviation: 68.79±4.32 years vs 63.77±4.84 years; p=0.03) but had similar body mass index (BMI; 27.15±1.06 kg/m2 vs 27.53±0.75 kg/m2; p=0.49). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was similar in both sexes (26.78±8.68% in women vs 23.71±6.04% in men; p=0.49). The proportion of patients with a history of myocardial infarction was slightly lower in women than in men (16.32±8.07% vs 22.35±10.59%; p=0.22). In line with a previous sex-specific analysis of the most relevant RCTs on antiplatelet therapies, our analysis showed a later onset of clinical manifestations of CCS/ACS in women69.

Figure 3. Mean enrolment rate of female participants in antithrombotic trials by year of publication. RCT: randomised controlled trial

Current pitfalls of RCTs

Sample size adjustments and sex-specific subanalysis

The underenrolment of women in cardiovascular (CV) trials has been increasingly recognised, and various strategies to improve female representation have been proposed30. To detect meaningful differences in both main treatment effects and interaction effects between women and men, the sample size of such trials would need to increase significantly70. This may be challenging because of increased costs and the lack of infrastructure to enrol so many patients within a reasonable timeframe. In addition, limitations arise from the phase before drug testing enters human clinical research, as animal studies have historically relied on male subjects71. Important features of a well-designed trial to provide robust sex-specific evidence include randomisation stratified by sex as well as the avoidance of exclusion criteria that (predominantly) affect women. With regard to the latter, pregnant and lactating women are often excluded based on a protection-by-exclusion strategy, even though this strategy deprives pregnant and lactating women of the benefits of contemporary therapies that would potentially improve their outcomes72. Moreover, barriers are routinely placed on women of childbearing potential in participating in clinical trials of antithrombotic therapies owing to concerns about adverse foetal effects of treatment. Nonetheless, anticoagulation poses unique challenges for women of reproductive age, and contraception recommendations in clinical trials may allow equity and access in clinical research66.

Historical data revealed that three-quarters of clinical cardiovascular trials published in leading general medical and cardiology journals did not report sex-specific analyses73. Despite federal legislation, national calls, and several author and reviewer guidelines underlining the importance of such analyses, this practice has not changed over the last decade7475.

The Lancet was the first journal to adopt a policy of encouraging researchers to enrol women and ethnic groups into clinical trials of all phases and to plan analyses of data by sex and race, including the enrolment of women in clinical trials and separate reporting of data by sex76. Clinical research studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine must include a table in the supplementary appendix that provides background information on the disease to ensure that study participants properly represent the patients affected by the condition being studied77.

Drug discontinuation

Among the current pitfalls of RCTs on antithrombotic therapies, study drug discontinuation and study retention among women should be listed. Higher odds of premature study drug discontinuation in women versus men may attenuate the observed treatment effect in intention-to-treat analyses and may blunt a potential safety signal. In 135,879 men and 51,812 women enrolled in 11 phase 3 and 4 trials conducted by the TIMI Study Group, and after adjusting for baseline differences, women had a 22% higher odds of premature drug discontinuation (adj. OR 1.22; 95% CI: 1.16-1.28) and were also more likely to withdraw consent compared with men (adj. OR 1.26; 95% CI: 1.17-1.36). The reason behind a higher drug discontinuation rate in women remains incompletely understood. This phenomenon is not explained by differences in age or comorbidities, appears in both active and placebo arms, and has been related and unrelated to bleeding complications7576. Withdrawal of consent and loss to follow-up may compound the interpretation of a possible drug’s efficacy or safety.

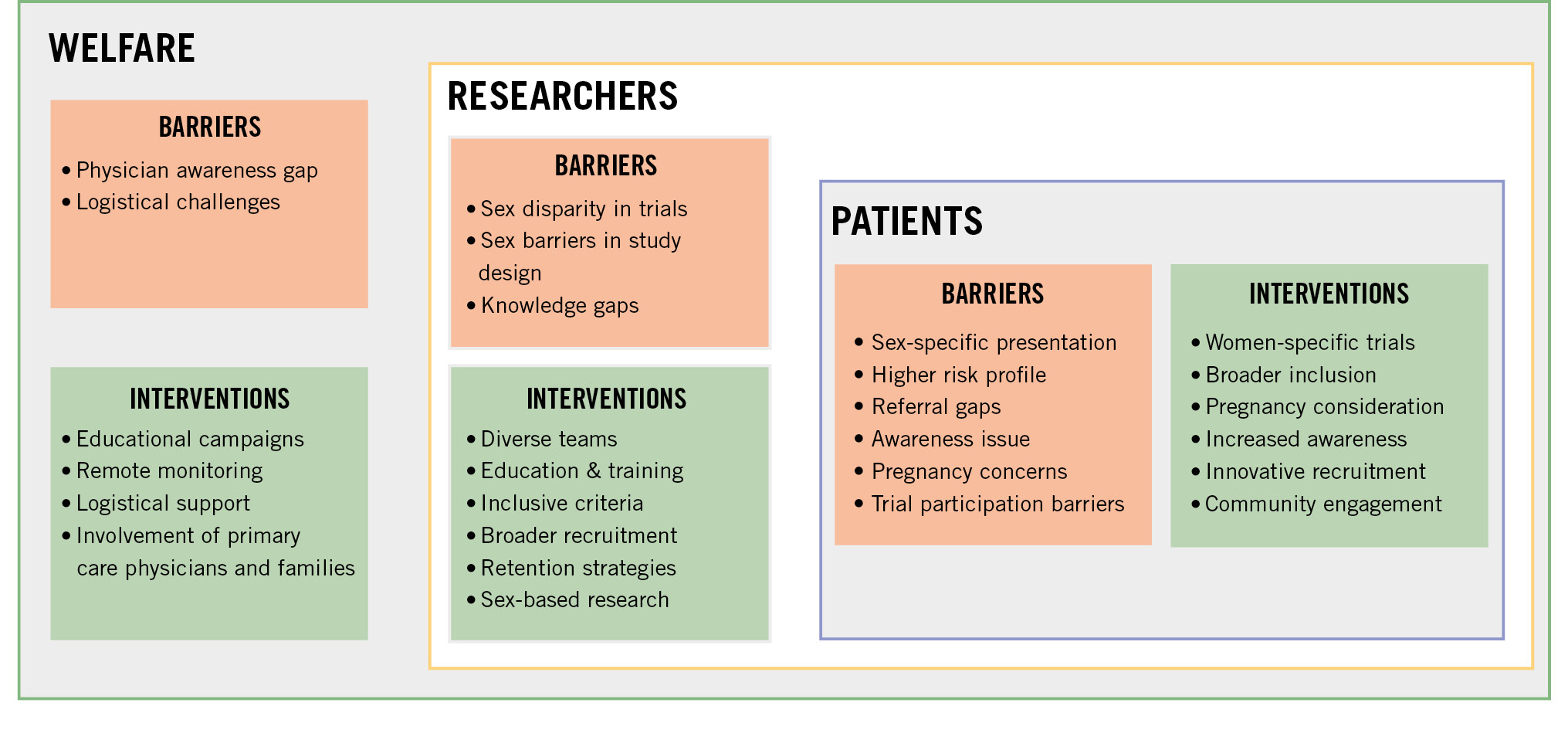

Current barriers to women’s enrolment and sex disparities in the research system

From 1993, the FDA started implementing guidelines encouraging women to participate in clinical trials. The action plan encouraged the completeness, quality, and transparency of demographic subgroup data. However, there is currently no FDA legal requirement for clinical trials to be powered to identify effects for subgroups based on sex, age, or other characteristics. Major barriers to the enrolment of women and minorities are related to cultural, social, and economic constraints. Although poorly investigated, factors such as competing priorities, caregiver roles, or transportation barriers may account for poor female enrolment and premature study discontinuation (Central illustration). Inadequate disease education and poor communication with the research team generate and amplify mistrust in the research system. The leaky pipeline of diversity in the leadership of clinical trials translates into the lack of diversity in enrolled populations. Women currently represent only 1 in 10 lead authors of cardiovascular trials published in high-impact journals, with a minority of first and last authors in cardiovascular research publications78. Trials led by female investigators enrol a greater proportion of females (7% higher mean in a recent study) and racial minorities, generating better evidence to assess for sex, race, or ethnicity as effect modifiers of intervention7980. Editorial leadership remains male dominated, and sex bias still affects the peer-reviewing process81. Sex disparities in the research system warrant further attention, both to ascertain causes of lower female study enrolment and to target actions that effectively improve female representation in clinical trials contributing to treatment recommendations.

Central illustration. Current barriers and potential interventions to improve the recruitment of women in cardiovascular trials.

Consensus statement: underrepresentation of women in RCTs

• It is advised to publish sex-specific data, such as the participation-to-prevalence ratio, withdrawal of consent, subanalyses including sex-treatment interaction, reporting adverse events and drug discontinuation by sex, and to provide full access to sex-disaggregated data in RCTs.

• Sample size adjustments and randomisation stratification by sex may be needed to detect relevant differences in treatment effect between women and men, although it may be difficult for economic and logistical reasons.

• All stakeholders from the research system (referring clinicians, investigators and coordinators in research teams, healthcare systems, healthcare administrations, funders, sponsors, professional, and community organisations) should act consistently to ensure the adequate representation of women in RCTs as participants and investigators.

• Action should be taken to increase female patient representation in RCTs such as organising educational campaigns, sharing of experiences by enrolled women, providing logistical support where needed, such as rideshare, childcare, or older adult care, limiting the number of onsite visits, making remote monitoring possible, offering flexible onsite study visitation hours, providing free transportation to study visits, proposing at-home follow-up, evaluating the reasons for study drug discontinuation and withdrawal of consent, expanding inclusion criteria, including pregnant and lactating women after satisfying results in pregnant animals, and involving primary care physicians and family members.

• Institutions, funding agencies and pharmaceutical companies should commit to advancing sex equality in academia at the level of principal investigators and leadership in RCTs. Such actions should have a measurable impact that is assessed through regular and transparent monitoring along the academic seniority pathway and should be incorporated in the rankings of universities and institutions.

Limitations

While transgender-inclusive trials have increased in the past two decades, most have focused on infectious diseases and mental health82. There remains a need for greater inclusion of transgender individuals in trials evaluating drugs and biologics for chronic diseases. Consequently, this consensus statement does not address cardiovascular health or provide recommendations on antithrombotic use in transgender women due to the limited quantity and quality of available data.

Conclusions

Despite significant advances in pharmacological and interventional treatments, CVD remains the leading cause of death among women. Differences between sexes in the risks of bleeding and thrombosis should be taken into consideration when using antithrombotic drugs. Importantly, the enrolment and retention of women in RCTs of antithrombotic therapy remain suboptimal and determine important gaps in evidence of drug safety. Barriers to the equal enrolment of women in CV trials have been attributed to several reasons, including patient characteristics, clinical research strategies, and behavioural, socioeconomic, and cultural factors8384. Clinical researchers, sponsors, community organisations, and federal agencies must work together to ensure that representative patient populations are enrolled in future studies.

Guest Editor

This paper was guest edited by Franz-Josef Neumann, MD, PhD; Department of Cardiology and Angiology, University Heart Center Freiburg - Bad Krozingen, Bad Krozingen, Germany.

Conflict of interest statement

V. Paradies declares research grants from Abbott via the institution; and speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Abbott, Boston Scientific, Novo Nordisk, and Elixir Medical, not related to this manuscript. F. Costa declares research grants from the European Research Council and the Italian Ministry of Health, not related to this manuscript. P. Capranzano declares speaker honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo and Amgen, not related to this manuscript. S. Degrauwe declares speaker fees from Medalliance, Cordis, Medtronic, SIS Medical, Shockwave Medical, Vascular Medical, Abbott, OrbusNeich, and Fumedica, not related to this manuscript. D.A. Gorog grants to the institution from Biotronik and Abbott; and speaker a research grant from AstraZeneca; and speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Chiesi and BMS/Janssen, not related to this manuscript. C.M. Jorge declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Daiichi Sankyo, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic, not related to this manuscript. C. Fraccaro declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Edwards Lifesciences and Boston Scientific, not related to this manuscript. D. Sibbing declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Bayer, Sanofi, Sandoz, and Daiichi Sankyo, not related to this manuscript. G. Vilahur declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation for AstraZeneca, not related to this manuscript. A. Chieffo declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Abiomed, Abbott Vascular, Cordis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Penumbra, not related to this manuscript. R. Mehran declares research grants from Abbott, Alleviant Medical, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Concept Medical, CPC Clinical Research, Cordis, Elixir Medical, Faraday Pharmaceuticals, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Medalliance, Mediasphere Medical, Medtronic, Novartis, Protembis GmbH, RM Global BioAccess Fund Management, and Sanofi US Services, Inc, via the institution; and speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Elixir Medical, IQVIA, Medtronic, Medscape/WebMD Global, and Novo Nordisk, not related to this manuscript. D. Capodanno declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Terumo, not related to this manuscript. E. Barbato declares speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Abbott, Medtronic, Insight, and Lifetech, not related to this manuscript. J.M. Siller-Matula declares research grants from AOP via the institution; and speaker fees from and advisory board participation for Daiichi Sankyo, Chiesi, Terumo, and Cordis, not related to this manuscript. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The Guest Editor reports consultancy fees from Novartis and Meril Life Sciences; speaker honoraria from Boston Scientific, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, and Meril Life Sciences; speaker honoraria paid to his institution from BMS/Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Boston Scientific, Siemens, and Amgen; and research grants paid to his institution from Boston Scientific and Abbott.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.