Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death amongst women, with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) representing a significant proportion. It has been reported that in women presenting with ACS there is underdiagnosis and consequent undertreatment leading to an increase in hospital and long-term mortality.

Several factors have to be taken into account, including lack of awareness both at patient and at physician level. Women are generally not aware of the cardiovascular risk and symptoms, often atypical, and therefore wait longer to seek medical attention. In addition, physicians often underestimate the risk of ACS in women leading to a further delay in accurate diagnosis and timely appropriate treatment, including cardiac catheterisation and primary percutaneous coronary intervention, with consequent delayed revascularisation times.

It has been acknowledged by the European Society of Cardiology that gender disparities do exist, with a Class I, Level of Evidence B recommendation that both genders should be treated in the same way when presenting with ACS. However, there is still a lack of awareness and the mission of Women in Innovation, in association with Stent for Life, is to change the perception of women with ACS and to achieve prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death amongst women1. The proportion of women with coronary artery disease (CAD) has risen markedly as life expectancy has increased, with a 32% estimated lifetime risk in women over the age of 40 years2.

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS), encompassing unstable angina (UA), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), represent a large portion of the clinical presentation of CAD. Prompt revascularisation is essential to reduce ischaemic complications in patients with STEMI and high-risk ACS3. Despite the high proportion of women developing ACS, this condition appears to be underdiagnosed and undertreated, with suboptimal use of revascularisation and medical therapy. There are a number of reasons for this, including a lack of awareness of the problem by the women themselves. Additionally, women may present with atypical symptoms leading to a delay in diagnosis, with a common misconception amongst healthcare providers of worse outcomes leading to less invasive management strategies in women. This article aims to review the issues surrounding gender disparities in the identification and treatment of ACS.

Gender differences in risk profiles

Women are typically older at presentation with ACS and have more comorbidities than their male counterparts4-16. It has been demonstrated that women presenting with ACS have a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease17. Conversely, women are less likely to be smokers or have suffered previous myocardial infarction (MI) or revascularisation. The reasons for these differences are multifactorial and may be a consequence of the development of CAD at a later age in women. This can be attributed to differences in endogenous sex hormone production, particularly oestrogen, which has a protective effect until the menopause3,18.

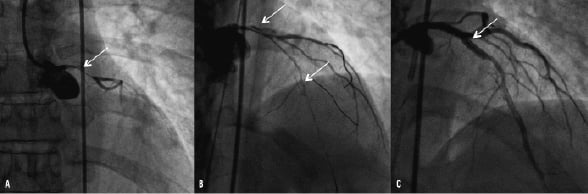

In addition, it has to be taken into account that women presenting with ACS more frequently have coronary arteries without significant lesions observed at coronary angiography19-22. In fact, more often women have microvascular dysfunction23, different plaque morphology24,25 and more common endothelial erosion21,22. Furthermore, in women presenting with ACS, different pathologies, such as spontaneous coronary artery dissection, are more frequent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An example of a less common presentation of acute coronary syndrome in a woman. This 45-year-old woman presented late to the emergency room and was subsequently delayed in diagnosis due to a lack of suspicion. Panel A demonstrates acute occlusion of the left main coronary artery (see arrow) secondary to spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Panel B demonstrates the extension of the dissection into the left anterior descending coronary artery (see arrow). Panel C shows the final result following percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of a 3.0×28 mm drug-eluting stent to seal the entry point of the dissection.

Gender differences in clinical presentation and diagnosis

Women may have atypical symptoms with the onset of ACS, including back or neck pain, pleuritic chest pain, indigestion and dyspnoea17,26-32. Alternative symptoms are not widely known to the general public and therefore not promptly recognised33. This leads to the first delay in the diagnosis of ACS. Indeed, it has been reported recently that women were more likely than men to present without chest pain (respectively 42.0% vs. 30.7%; p<0.001)34.

Following presentation to healthcare providers, ACS may not be suspected initially, due to an unclear history and general underestimation of CAD risk in women. Therefore, there is a delay in ECG acquisition, recognition of the problem and timely management. This results in the second delay in the diagnosis of ACS.

Notably, it has been reported that women more often present with UA/NSTEMI within the ACS spectrum compared with men17 and this could explain the generally less “invasive” management. However, mortality after NSTEMI at longer-term follow-up is actually higher35. An online survey study to assess adherence to national cardiovascular guidelines, which included 100 cardiologists, demonstrated that despite a similar calculated risk women were assigned to a lower risk category for CAD than men36. Moreover, it has been reported that the most commonly cited rationale for undertaking a conservative approach in women was the perception by healthcare providers that they were at lower risk37.

However, despite the misconception of lower risk, it has been demonstrated that females with ACS actually present with more signs of heart failure than their male counterparts5. In these patients, there may actually be more to gain from early invasive treatment and revascularisation, which women may otherwise be denied.

Gender differences in ACS management

MEDICAL THERAPY

It has been shown that, when women present with a suspected ACS, they are less likely to receive aspirin (odds ratio [OR] 1.16; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13-1.20; p<0.01) or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.08-1.13; p<0.01)17. A similar reduction in proven therapies was demonstrated at follow-up, with less optimal medical therapy prescribed, including beta-blockers and lipid-lowering agents4-6,9,17,29,38-40. Underutilisation of optimal evidence-based therapies can be associated with multiple factors, including age, the consequences of disease and the physician’s decision to catheterise41.

REVASCULARISATION IN STEMI

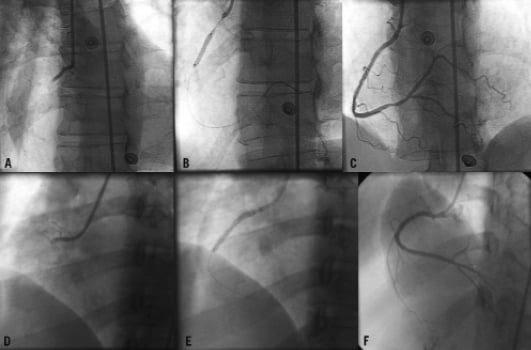

The benefit of early reperfusion in STEMI in both genders is now unquestionable and is reflected in current practice guidelines42. Despite this, even in patients presenting with STEMI, women have been shown to be less likely to be admitted to a hospital with the ability to perform percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)43. In a recent study from Poland of 26,035 patients (34.5% were female), fewer women with STEMI underwent primary PCI earlier than 12 hours from symptom onset (35.8% vs. 44.0%; p<0.0001)9. Indeed, there was not only a significant difference in the onset to balloon time (255 [IQR 175-375] minutes vs. 241 [IQR 165-360] minutes; p<0.0001) but also in the door to balloon time (45 [IQR 30-70] minutes vs. 44 [IQR 30-68] minutes; p=0.032). This confirms delays not only in patient presentation, but also in the identification and management decision by the medical profession as described above. Examples of delay in diagnosis and treatment of STEMI in women are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Examples of delayed diagnoses and treatment of women with STEMI. The upper panels A, B and C show evidence of an acute thrombotic occlusion of the right coronary artery on coronary angiography of a 58-year-old female Caucasian patient. She presented with a 14-hour history of chest pain, treated with direct 3.0×16 mm bare metal stent implantation, with a good final angiographic result. Panels D, E and F show a subacute right coronary artery occlusion (two-day history of intermittent chest pain) of a 37-year-old Sri Lankan, treated with two (3.0×28 mm and 3.0×13 mm) bare metal stents and good final result.

A large registry of 74,389 patients (30.0% women) again demonstrated a lower rate of PCI with stent in women (14.2% vs. 24.4%; p<0.001) with a subsequent higher rate of in-hospital mortality in women (respectively 14.8% vs. 6.1%; p<0.0001)39. Furthermore, a large study of 1,143,513 patients (42.1% women) showed that younger women (<45 years) presenting without chest pain had a higher mortality than men of the same age group (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.00-1.39)34. However, a recent study has shown that despite female gender being a predictor of early death, it does not appear to be a predictor at 12 months (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.96-1.09; p=NS)9.

REVASCULARISATION IN NSTEMI

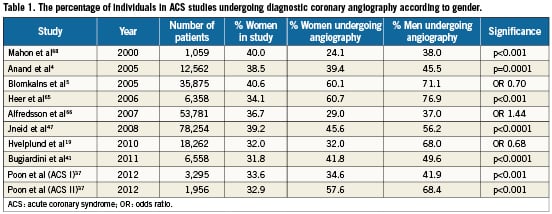

Numerous studies have demonstrated that in this high-risk population women are offered cardiac catheterisation and PCI less frequently than men (Table 1). Regarding the management of NSTEMI, the advantage of an early invasive strategy in women has been less clear than in males, with prior interventional studies, including the “Fragmin and Fast Revascularization during In Stability in Coronary artery disease” (FRISC) II and the “Randomised Intervention Trial of unstable Angina” (RITA) 3 trials, demonstrating a clear benefit with a routine early invasive strategy in men, but not in women20,44. However, interestingly in the FRISC II trial, the higher event rate in females treated with an early invasive strategy seemed largely due to an increased rate of death and MI in the women undergoing CABG20.

Conversely, the “Treat Angina with Aggrastat and Determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction-18” (TACTICS-TIMI 18) trial showed a similar benefit of an early invasive strategy between genders in those with elevated biomarkers22. A further sex specific analysis showed a comparable benefit in both men and women if they were creatine kinase or troponin positive. However, those women with negative enzymes had higher event rates with an early invasive strategy45.

More recently, a gender substudy of the “Organization for the Assessment of Strategies for Ischemic Syndromes” (OASIS) 5 trial showed no differences between routine invasive or selective invasive (coronary angiography only if symptoms or signs of severe ischaemia) strategies in the primary outcome of death, MI or stroke; however, of note, there was a higher rate of death with a routine invasive strategy46. This was suggested to be due to the fact that women have less obstructive coronary stenoses, thereby diluting the treatment benefit in addition to more risk associated with CABG as suggested in the FRISC II trial. However, even after adjustment for the extent of disease, age and comorbidities, women with ACS have still been shown to be less likely to be revascularised19.

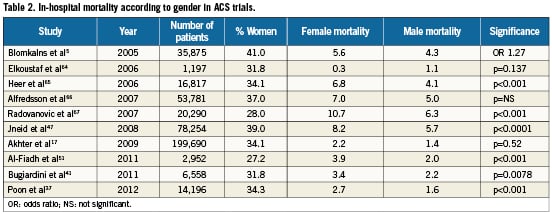

A number of studies have demonstrated increased in-hospital mortality amongst women following ACS (Table 2). A large US “Get With The Guidelines Coronary Artery Disease Database” of 78,254 patients with both STEMI and NSTEMI, of which 39.0% were female, demonstrated an unadjusted mortality of 8.2% in women compared to 5.7% in men (p<0.0001). Following multivariable adjustment, despite the fact that these differences were no longer observed in the overall cohort (adjusted OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.99-1.10), in the STEMI group there remained a higher mortality in women (respectively 10.2% vs. 5.5%; p<0.0001)47. A contemporary study of 14,196 NSTEMI patients in Canada showed women had a higher in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR 1.26; 95% CI 1.02-1.56; p=0.036), irrespective of age (p for interaction 0.76)37.

Conversely, in the “Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines” (CRUSADE) registry, no difference according to adjusted in-hospital mortality between women and men was observed (respectively 5.6% vs. 4.3%; adjusted OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.90-1.13)5.

The lack of gender-related difference in mortality has frequently been reported in registry studies in which women and men with acute MI underwent primary PCI17,48,49. The American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry of 199,690 patients (34.0% women) showed an adjusted in-hospital mortality similar amongst genders (women 2.2% vs. men 1.4%; p=0.52)17.

A mortality difference in patients less frequently treated with PCI has also been demonstrated at more long-term follow-up. The Canadian Acute Coronary Syndrome registry demonstrated a significant difference in mortality at 12 months between genders (women 10.47% vs. men 8.02%; p=0.0017)41. However, in the majority of registry studies in which the proportion of revascularised patients is high, no differences in long-term mortality have been reported48,50-52. Interestingly, women who underwent primary PCI within the first 48 hours after symptom onset did benefit more than their male counterparts (age-adjusted mortality risk at one year after revascularisation 0.65; 95% CI 0.49-0.87; p=0.004)48. A higher degree of myocardial salvage after reperfusion in women compared to men might be a possible explanation for these findings49.

Recently, although the Task Force for the management of ACS in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology acknowledged that gender disparities do exist, they nevertheless recommended a Class I, Level of Evidence B indication that both genders should be treated in the same way when presenting with ACS53.

Figure 3 demonstrates a thrombotic sub-occlusive left anterior descending coronary artery lesion in a 53-year-old woman presenting with NSTEMI. It is imperative that each individual should follow careful risk stratification for ischaemic and bleeding risks, incorporating clinical evaluation, biomarkers, comorbidities and risk scores.

Figure 3. NSTEMI in a 53-year-old woman, with a history of breast cancer treated with mastectomy, presenting with sudden onset chest pain. Despite no changes on electrocardiogram, echocardiography revealed some apical hypokinesia. The patient therefore underwent coronary angiography which demonstrated a subocclusive thrombotic lesion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery (Panel A arrowed), treated successfully with a 3.0×16 mm bare metal stent (Panel B).

BLEEDING AND VASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

Higher rates of procedural complications, in particular vascular complications and bleeding, can be increased as much as fourfold in the female population3,9,17,54. Female sex has been shown to be an independent predictor of bleeding in several ACS trials with different anticoagulation strategies50,55-57. Furthermore, the “Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events” (GRACE) registry demonstrated the adjusted OR for bleeding was 1.71 (95% CI 1.35-2.17) in women compared with men58. Nevertheless, the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors has not been reported as an independent risk for major vascular complications in women3,59,60.

In recent years much focus has been placed on reducing bleeding in patients requiring urgent intervention, with bivalirudin emerging as a possible alternative in STEMI patients61. Furthermore, in a gender sub-analysis of the “Randomised comparison of Bivalirudin versus Heparin in patients undergoing early invasive management for acute coronary syndrome without ST elevation” (ACUITY) study, comprising 13,819 patients (30.1% women), the use of bivalirudin monotherapy rather than heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors reduced the rate of major bleeding at 30 days in the women undergoing PCI (12.0% vs. 6.0%; p<0.001) without an increase in ischaemia-driven outcomes. Furthermore, treatment with heparin rather than bivalirudin was an independent predictor of major bleeding (hazard ratio [HR] 1.7; 95% CI 1.3-2.22; p=0.0002)50.

Under-representation of women in ACS trials

It is important to emphasise that historically women have been poorly represented in coronary clinical trials, typically comprising approximately 30% of the overall population. Several factors have to be taken into account, including inclusion criteria such as age, clinical presentation and timing of onset of symptoms. In addition, social factors should also be considered, such as less likelihood of women participating in clinical studies. The under-representation of women in clinical trials may clearly lead to an important bias in the interpretation of the results and subsequently to extending these to the female population. Clinical trials in the setting of ACS, with a larger representation of women and dedicated questions for gender-based issues, are warranted in order to understand better the pathophysiology of CAD and ACS in women and to ensure a tailored treatment of this patient population.

Conclusions

Women with ACS tend to present later, face delays in diagnosis, undergo less invasive management and receive less effective medical management than their male counterparts. It is essential that as medical practitioners we aim to reduce these gender disparities in ACS management and ensure that women receive appropriate treatment from which they can benefit. The barriers that contribute to treatment disparities in women require further investigation. Women in Innovation, in association with Stent for Life, aim to develop greater awareness of this problem which may assist in bridging the gap between current guidelines and management practices62,63.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Mehran receives research grants from Sanofi/BMS, TMC and DSI/Lilly and is a Consultant/Advisory Board for Regado Biosciences, AstraZeneca, Abbott Vascular and Janssen. The other authors have nothing to disclose in relation to this manuscript.