Since the publication of the first landmark studies on sex and gender differences in the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in 1991, this fascinating topic has never left my mind1,2. Having been a cardiologist for three years at the time, I was increasingly asked by my female patients why I could not answer their questions on the origin of their symptoms and why I did not have appropriate treatment options. During the 1980s, I had learned in my cardiology training that women with chest pain were “weird” with strange and atypical symptoms. They almost never fitted into the diagnostic work-up that we routinely performed in patients suspected of having ischaemic heart disease (IHD), this being an exercise test, followed by nuclear SPECT imaging and/or being sent directly for heart catheterisation. Too often we felt “deceived” by their “normal” angiograms and the lack of interventional options to treat their symptoms. The easiest way out was to consider these symptoms as “psychological distress”.

What makes CAD in women so different from our male-oriented standard?

The impressive developments in interventional cardiology and cardiac imaging over the past decades have made it obvious that important sex differences in the extent and pattern of coronary artery disease (CAD) do exist. Women have coronary arteries of a smaller diameter, even when corrected for body surface area. They have fewer calcifications, less focal obstruction and a more diffuse pattern of atherosclerosis with “outward remodelling” and “soft” plaques at all ages3,4. In addition, at older age, women have more vascular and myocardial stiffness, leading to a higher risk of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, strokes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). In the large Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR), almost 80% of women under 60 years of age with stable angina symptoms had no visible coronary obstructions on angiography, compared with 40% of men5. Although CAD progresses with ageing, this sex difference in atherosclerosis burden persists into old age. Women with angina twice as often have ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) often combined with coronary (micro-)vascular dysfunction, which has important consequences for their clinical symptoms, diagnostic strategies, treatment options and outcomes6,7. An increasing number of follow-up studies have confirmed that INOCA is a heterogeneous and not a benign condition, with outcomes importantly related to the presence of “some” CAD and the number of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors7-9. The fact that in nearly all PCI registries around 75% males and 25% females are included may be partly caused by selection bias, but also by true sex differences in coronary atheroma burden and more focal stenoses in men. The EAPCI Women Committee rightly warns to be cautious in generalising data from PCI registries and randomised trials to all female patients, as the majority of data are based on men10. Although abundant data have been published on major adverse cardiac events (MACE) after PCI, the presence of residual symptoms and adverse patient-reported outcomes are more often present in women11. These clinically relevant subjective parameters need more attention as they have an important effect on their quality of life.

MINOCA: fake findings have shifted into a true diagnosis

Whereas we felt frustrated in the 1980s by the “normal” angiograms in so many women, we now acknowledge their ACS as true myocardial infarctions with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). This type of ACS dominates in younger women and is a working diagnosis that needs more clarification of the underlying coronary disorder, such as vasomotor dysfunction (type II ACS), coronary plaque disruption or thromboembolism12. More frequent use of intracoronary measurements and imaging techniques as well as provocative testing may be helpful in these patients. This is especially important as many of these (relatively) young women are still sent home too often without an appropriate diagnosis and treatment advice.

Next to MINOCA, women have relatively more other variant ACS, such as spontaneous coronary artery dissections (SCADs) and Takotsubo cardiomyopathies. Up to 34% of ACS in women below 60 years of age are estimated to be caused by a SCAD, that may mimic coronary atherosclerosis. In a recent position paper of the ESC working group on SCAD, attention is paid to different treatment advice in SCAD patients from the existing STEMI and NSTEMI guidelines13. Prolonged use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), for instance, may increase intravascular haemorrhage and even result in severe anaemia due to heavy uterine bleeding.

The high-risk woman beyond traditional risk factors

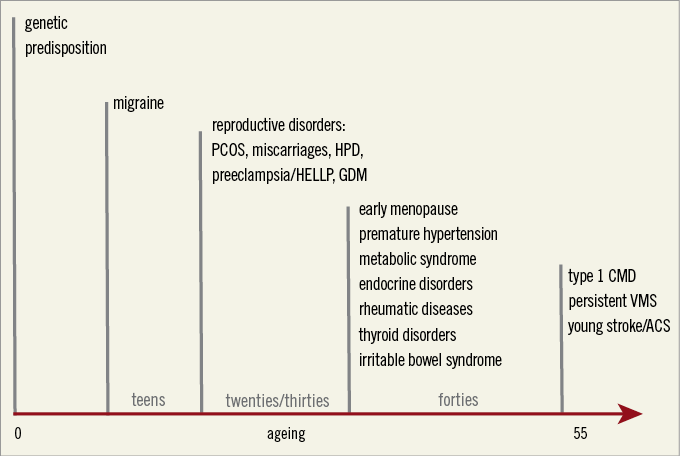

As we have learned over the past decades that patients are not “gender neutral”, we should apply this knowledge in clinical practice and be more creative in using sex- and gender-specific characteristics to identify high-risk patients at a young age. In women, a history of premenopausal migraine, hypertensive pregnancy disorders (HPD), young age at menopause and inflammatory comorbidities are all indications of a higher risk for premature CVD, beyond the traditional CVD risk factors that dominate at older age14. These risk variables are very helpful tools in clinical decision making in symptomatic women at middle age (Figure 1). Now that cardiology has entered the era of personalised medicine, we can no longer ignore that the female patient should be treated as a lady.

Figure 1. Female-specific risk variables to identify women at risk for premature cardiovascular disease. ACS: acute coronary syndromes; CMD: coronary microvascular dysfunction; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; HELLP: haemolysis elevated liver enzymes low platelets syndrome; HPD: hypertensive pregnancy disorders; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; VMS: vasomotor symptoms. Adapted from reference 14, with permission.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.