Abstract

Aims: Our aim was to assess whether bivalirudin compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH) is associated with consistent outcomes in males and females with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing invasive management.

Methods and results: In the MATRIX programme, 7,213 patients were randomised to bivalirudin or UFH. Patients in the bivalirudin group were subsequently randomly assigned to receive or not a post-PCI bivalirudin infusion. The 30-day co-primary outcomes were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, and net adverse clinical events (NACE), defined as MACE or major bleeding. The primary outcome for the comparison of a post-PCI bivalirudin infusion with no post-PCI infusion was a composite of urgent target vessel revascularisation (TVR), definite stent thrombosis (ST), or NACE. The rate of MACE was not significantly lower with bivalirudin than with heparin in male (rate ratio [RR] 0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.75-1.07; p=0.22) and female patients (RR 1.06, 95% CI: 0.80-1.40; p=0.67) without significant interaction (pint=0.31), nor was the rate of NACE (males: RR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.72-1.01; p=0.07; females: RR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.76-1.28; p=0.91; pint=0.38). Post-PCI bivalirudin infusion, as compared with no infusion, did not significantly decrease the rate of urgent TVR, definite ST, or NACE (males: RR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.66-1.07; p=0.15; females: RR 1.06, 95% CI: 0.74-1.53; p=0.74; pint=0.28).

Conclusions: In ACS patients, the rates of MACE and NACE were not significantly lower with bivalirudin than with UFH in both sexes. The rate of the composite of urgent TVR, definite ST, or NACE was not significantly lower with a post-PCI bivalirudin infusion than with no post-PCI infusion in both sexes.

Introduction

Over the past decade, antithrombotic therapies after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have improved outcomes more in men than in women1,2, raising the question as to whether there are sex-specific differences in treatment patterns and response to such therapy. However, there is contrasting evidence on the impact of sex on clinical outcomes, particularly on overall and cardiovascular mortality, in patients treated for coronary artery disease. There are also differences in presenting clinical characteristics and pathophysiologic profile, as well as disparities in treatment which may contribute considerably to this outcome discrepancy3. A large body of evidence suggests that female patients have increased periprocedural bleeding risk as compared to males4,5. Recently the radial access has been shown to be effective in reducing such risk compared to the femoral access in ACS patients managed invasively6.

We sought to investigate whether the use of bivalirudin, either continued or discontinued after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), instead of unfractionated heparin (UFH), might be associated with consistent or differential efficacy and safety effects in male and female patients with ACS undergoing invasive management as part of a pre-specified analysis in the Minimizing Adverse Haemorrhagic Events by TRansradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of angioX (MATRIX) programme.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN, OUTCOMES AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The design and main results of the MATRIX trial have been reported previously7,8,9. Details are shown in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Results

PATIENTS

From October 2011 to November 2014, at 78 centres in Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden, 3,610 patients were assigned to receive bivalirudin (males: 2,731, 75.7%; females: 879, 24.3%), either with a post-PCI infusion (1,799 patients [males: 1,351, 75.1% and females: 448, 24.9%]) or without a post-PCI infusion (1,811 patients [males: 1,380, 76.2% and females: 431, 23.8%]), and 3,603 were assigned to receive UFH (males: 2,764, 76.7%; females: 839, 23.3%).

Female and male subgroups allocated to bivalirudin versus UFH and to post-PCI bivalirudin infusion versus no post-PCI infusion were generally well matched in terms of demographics, medical history, clinical presentation, procedural aspects and therapy at discharge (Supplementary Table 1-Supplementary Table 3).

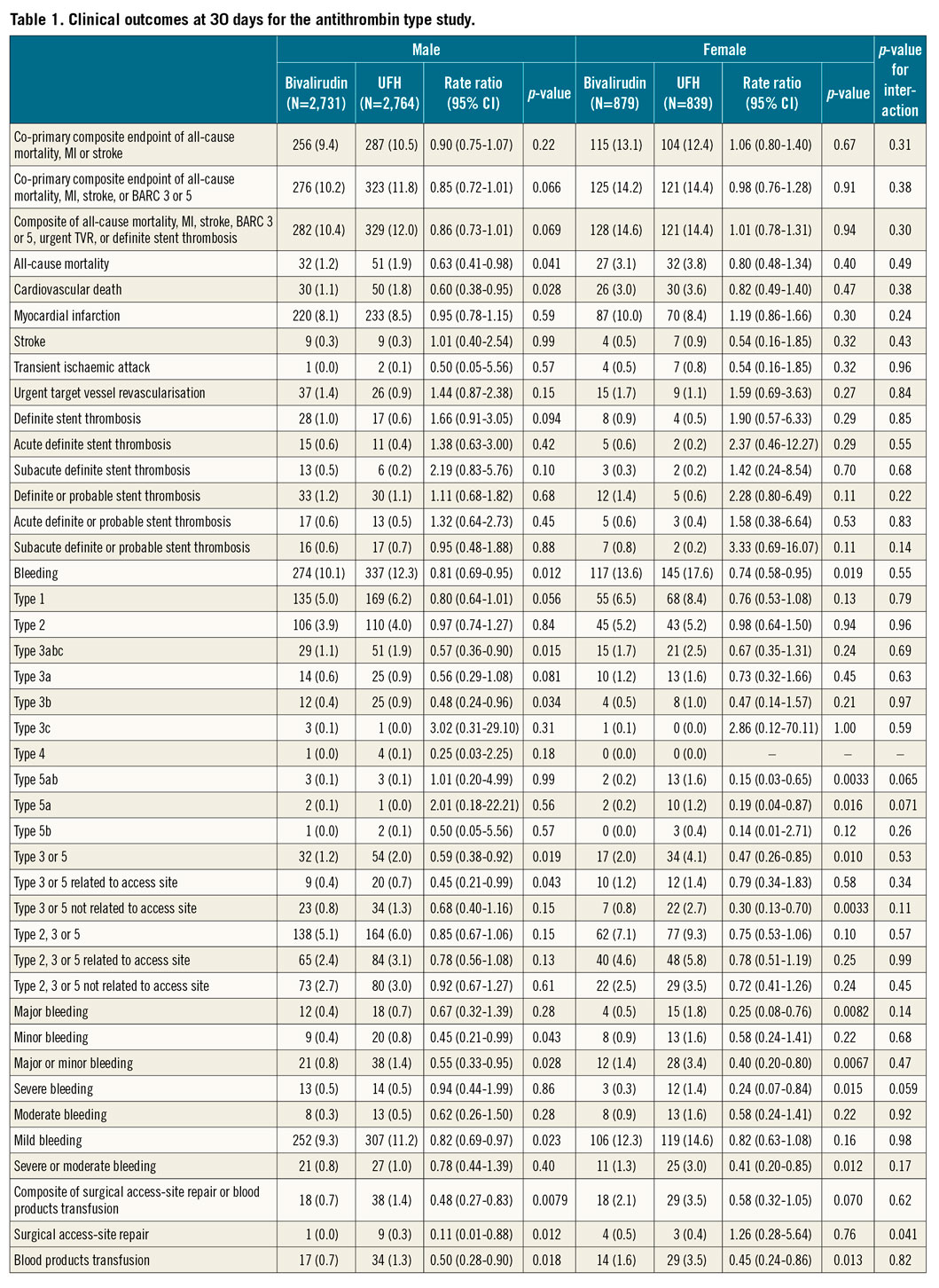

CLINICAL OUTCOMES ACCORDING TO ANTITHROMBIN TYPE

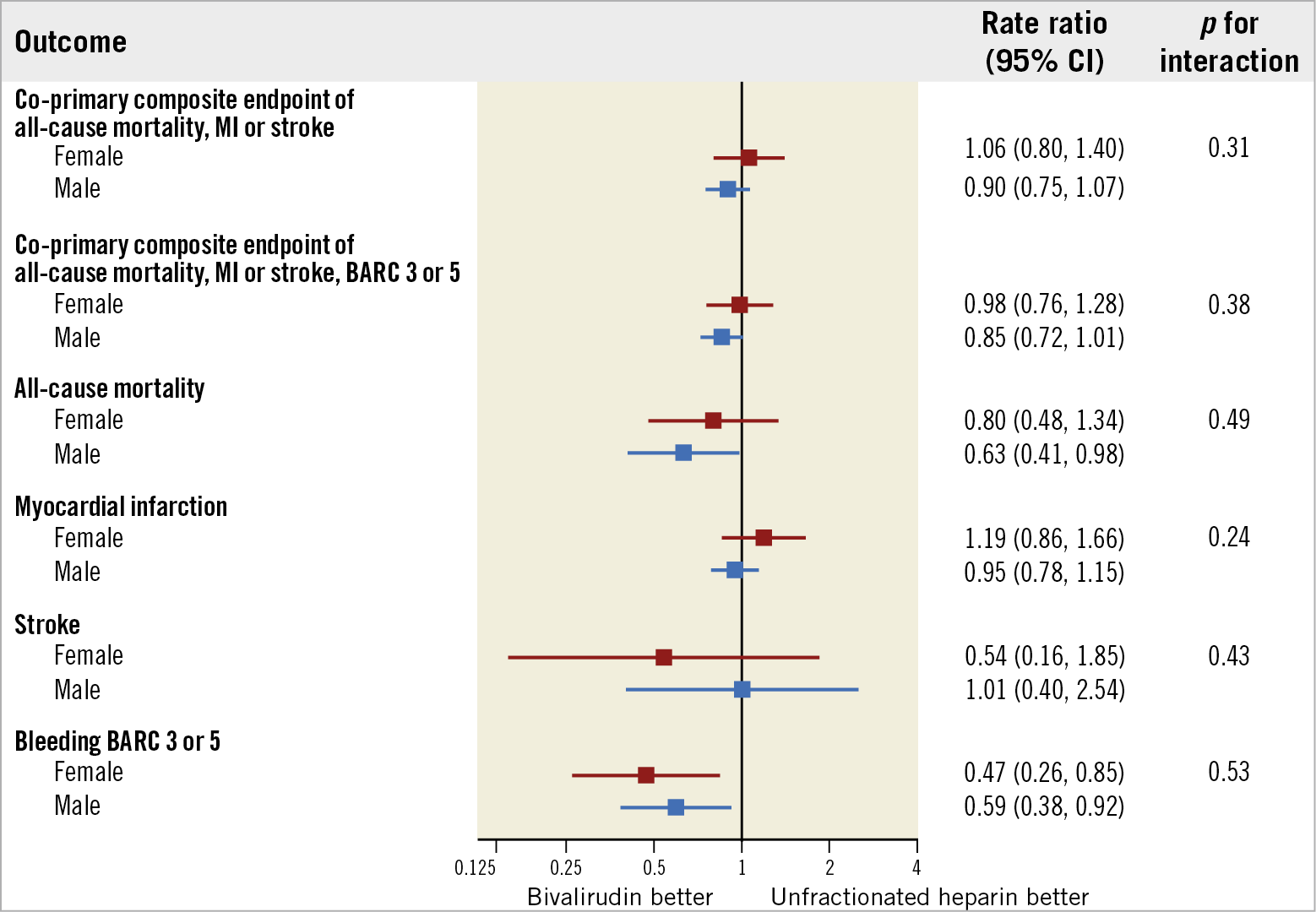

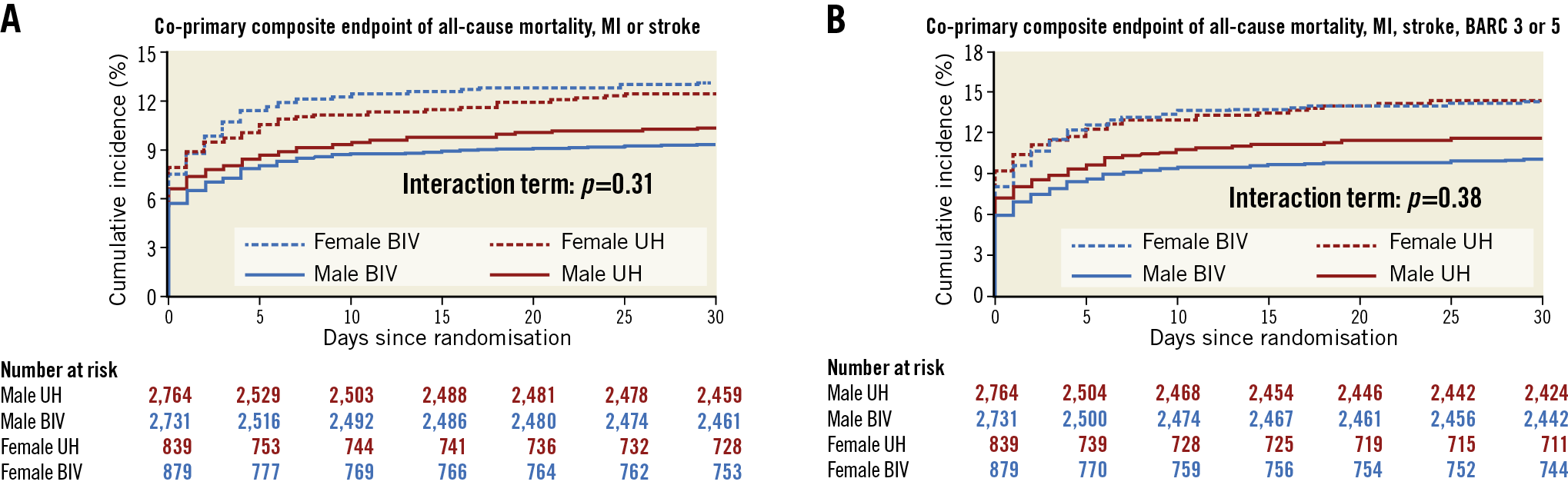

MACE occurred in 256 patients (9.4%) in the bivalirudin group and in 287 patients (10.5%) in the UFH group (rate ratio [RR] 0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.75 to 1.07; p=0.22) in males and in 115 (13.1%) and 104 (12.4%) females (RR 1.06, 95% CI: 0.80 to 1.40; p=0.67) without significant interaction (pint=0.31) (Table 1, Figure 1, Figure 2). A total of 276 patients (10.2%) in the bivalirudin group, as compared with 323 patients (11.8%) in the UFH group, had a NACE (RR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.72 to 1.01; p=0.07) in males, and 125 (14.2%) as compared with 121 (14.4%) female patients had a NACE (RR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.28; p=0.91) without significant interaction (pint=0.38) (Table 1, Figure 1, Figure 2).

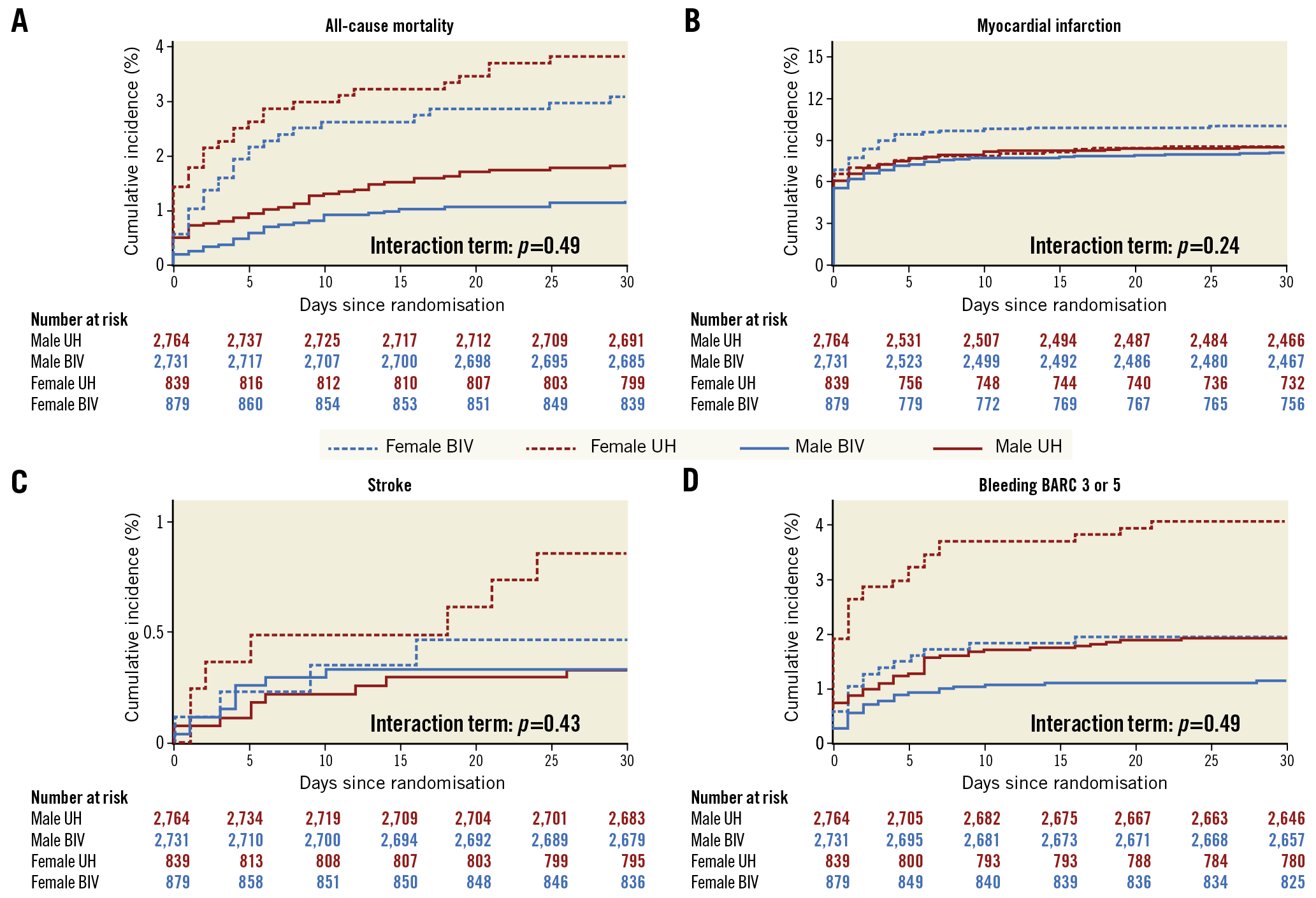

Figure 1. Main outcomes of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in male and female patients. Bivalirudin and UFH were compared on the basis of sex subgroups, with rate ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for the co-primary endpoints and their components (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, BARC 3 or 5).

Figure 2. Co-primary composite outcomes of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin at 30 days in male and female patients. A) & B) Cumulative incidence of the co-primary outcomes of MACE and NACE, respectively. Blue indicates bivalirudin, red indicates UFH, continuous line indicates male, dashed line indicates female.

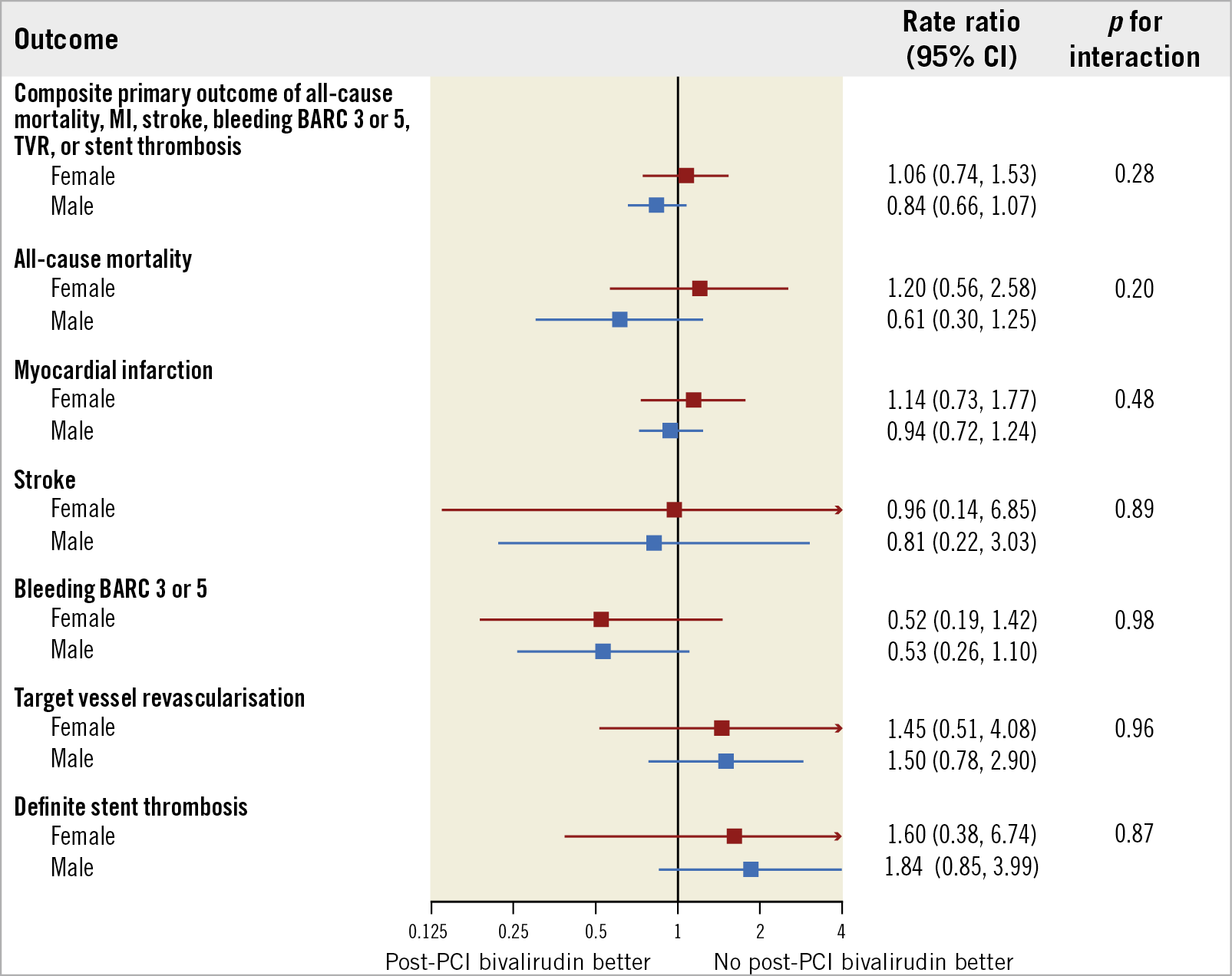

Compared with UFH, bivalirudin was apparently associated with a lower rate of all-cause death in male (1.2% vs. 1.9%; RR 0.63, 95% CI: 0.41 to 0.98; p=0.041) but not in female patients (3.1% vs. 3.8%; RR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.48 to 1.34; p=0.40); however, there was no detectable signal of heterogeneity across genders (pint=0.49) (Table 1, Figure 1, Figure 3). This was similarly observed for cardiovascular death (males: 1.1% vs. 1.8%; RR 0.60, 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.95; p=0.028; females: 3.0% vs. 3.6%; RR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.49 to 1.40; p=0.47; pint=0.38) (Table 1). There were no significant differences between bivalirudin and UFH in both male and female patients for the rates of individual endpoints of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, target vessel revascularisation (TVR), and stent thrombosis (ST) (Table 1, Figure 1, Figure 3). Bivalirudin consistently reduced rates of major bleeding (BARC 3 or 5) compared with UFH across genders (males: 1.2% vs. 2.0%; RR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.92; p=0.019; females: 2.0% vs. 4.1%; RR 0.47, 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.85; p=0.01; pint=0.53) (Table 1, Figure 1, Figure 3). This difference was mainly driven by access-related events in males and by non-access-related bleeding in females, with fatal, TIMI major and GUSTO severe bleeding being lower in female patients only (Table 1).

Figure 3. Components of co-primary composite outcomes of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin at 30 days in male and female patients. Panels show the cumulative incidence of the co-primary outcome components of all-cause death (A), myocardial infarction (B), stroke (C), and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (D). Blue indicates bivalirudin, red indicates UFH, continuous line indicates male, dashed line indicates female.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES ACCORDING TO BIVALIRUDIN TREATMENT DURATION

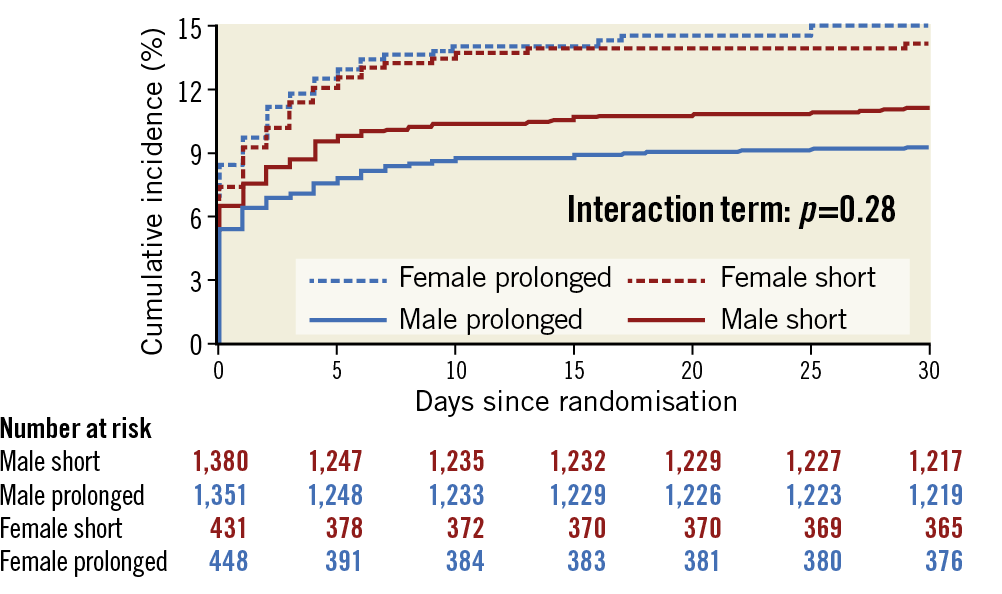

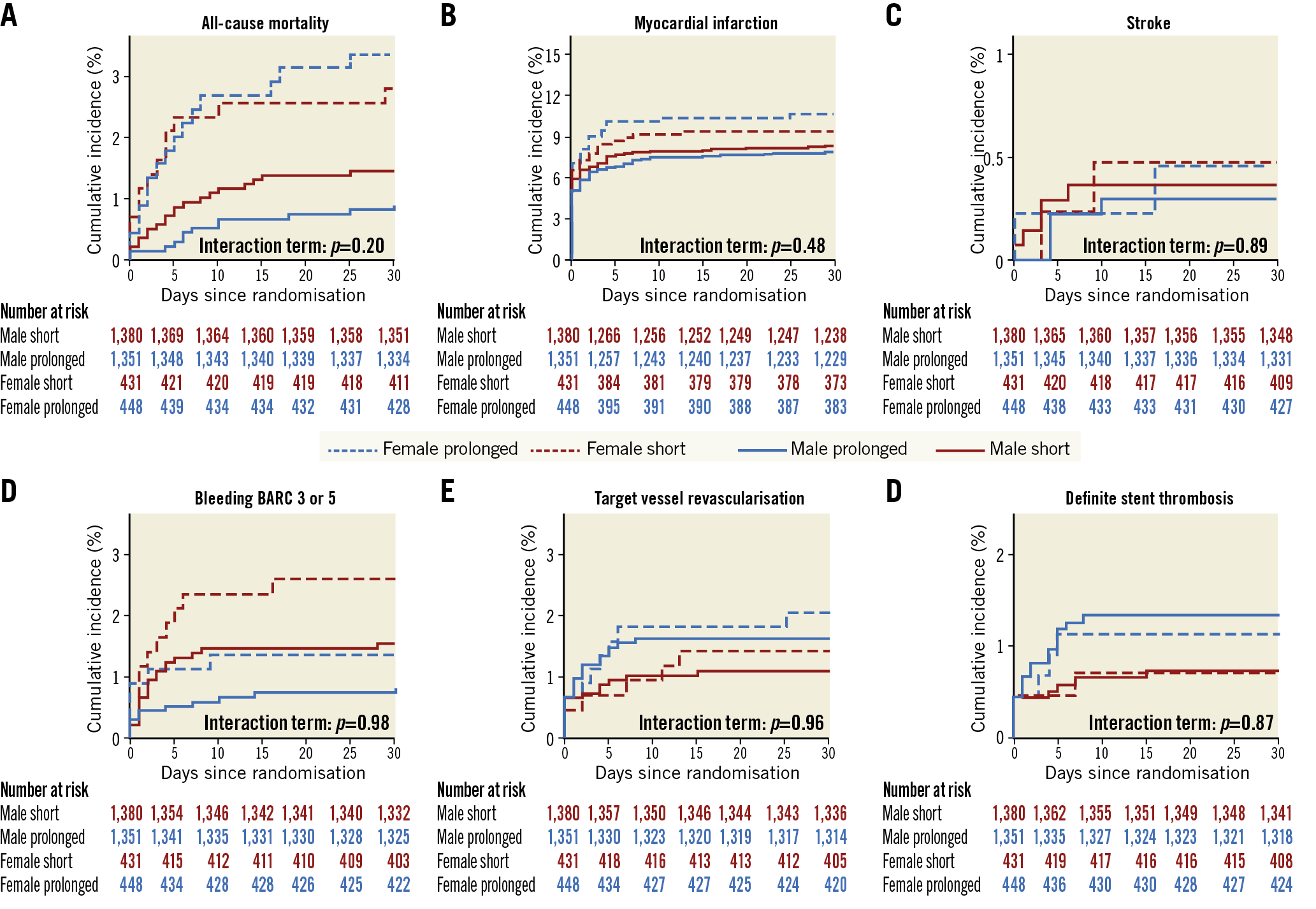

The primary composite outcome was observed in 128 patients (9.6%) who received post-PCI bivalirudin and in 154 patients (11.2%) who did not receive post-PCI bivalirudin (RR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.66 to 1.07; p=0.15) in males and, respectively, in 67 (15.0%) versus 61 female patients (14.2%) (RR 1.06, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.53; p=0.74) (pint=0.28) (Supplementary Table 4, Figure 4, Figure 5). No significant differences or interactions were observed in terms of MACE, NACE, or individual endpoints of death, MI, stroke, TVR or ST (Supplementary Table 4, Figure 6).

Figure 4. Main outcomes of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion versus no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion in male and female patients. Bivalirudin infusion and no infusion post PCI were compared on the basis of sex subgroups, with rate ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for the primary endpoint and its components (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, BARC 3 or 5, urgent TVR and definite ST).

Figure 5. Primary composite outcome of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion versus no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion at 30 days in male and female patients. Cumulative incidence of the primary composite outcome of urgent TVR, definite ST, or NACE. Blue indicates prolonged bivalirudin infusion, red indicates no post-PCI infusion, continuous line indicates male, dashed line indicates female.

Figure 6. Components of primary composite outcome of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion versus no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion at 30 days in male and female patients. Panels show the cumulative incidence of the primary outcome components of all-cause death (A), myocardial infarction (B), stroke (C), BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (D), urgent TVR (E) and definite ST (F). Blue indicates prolonged bivalirudin infusion, red indicates no post-PCI infusion, continuous line indicates male, dashed line indicates female.

There was no significant between-group heterogeneity in the rate of bleeding, with BARC 2 events being significantly higher in male and numerically higher in female patients in the post-PCI bivalirudin arm, while BARC 3 or 5 events which were not related to the access site were lower in both sexes (Supplementary Table 4).

ADDITIONAL ANALYSES

Supplementary Figure 1-Supplementary Figure 4 list the effect of randomised antithrombin type on MACE and NACE in male and female patients according to pre-specified subgroups. In male patients, the randomised treatment effect appeared consistent across most subgroups, with the exception of patients with an increased body mass index (BMI) or those with prior exposure to UFH, in whom bivalirudin, as compared to UFH, lowered MACE and NACE. The treatment effect was also largely consistent in female patients.

Supplementary Figure 5-Supplementary Figure 8 show the effect of randomised bivalirudin treatment duration on MACE and NACE in male and female patients according to pre-specified subgroups.

Discussion

MATRIX is the largest randomised study on bivalirudin in STEMI, one of the largest in NSTE-ACS patients, and the only randomised comparison of post-PCI versus no post-PCI bivalirudin infusion. The study failed to show that bivalirudin as compared to UFH±GPI reduces MACE or NACE, and post-PCI bivalirudin infusion did not reduce the rate of the primary endpoint compared with no post-PCI infusion. In secondary endpoint analyses, bivalirudin compared to UFH±GPI decreased the rate of fatalities and the risk of major bleeding, mainly non-access-site related, in both randomly allocated access sites.

The results of the sex-based pre-specified analysis can be summarised as follows:

1) There was no signal of heterogeneity across sexes for any of the primary endpoints, including MACE and NACE for the bivalirudin versus UFH±GPI comparison and the composite of NACE, definite ST and urgent TVR for the assessment of post-PCI bivalirudin infusion.

2) In secondary stratified analyses, bivalirudin remained associated with lower risks of mortality and bleeding in both sexes, with no signal of a sex-based treatment effect on interaction testing. Mortality was numerically lower with bivalirudin in both female and male patients, albeit it reached statistical significance in the latter group only, probably reflecting a power issue. BARC 3 or 5 bleeding was significantly reduced in both sexes, interestingly owing to a reduction of access-site events in males and non-access-site-related occurrences in females.

Sex differences in cardiovascular outcomes is a topic of great interest and debate in the cardiology community, with data supporting such a discrepancy as opposed to others suggesting that women treated for coronary artery disease have different clinical, procedural and treatment profiles compared with men, which may largely explain the observed dissimilarities in prognosis. Indeed, after correcting for sex-based confounders, such disparities, particularly in mortality and major composite endpoints, seem to be no longer demonstrated3,6. However, female patients have been associated with higher rates of periprocedural bleeding4,5. This was also confirmed in a previous pre-specified analysis of MATRIX where we observed a greater risk of access-site bleeding and transfusion rates in female as compared with male patients after adjusting for confounders6. Additional interest in this topic is related to the fact that women represent a limited number of patients included in the majority of cardiovascular trials. Against this background, it seems particularly relevant to explore whether there are sex-specific differences in treatment patterns and response to antithrombotic therapy.

In a patient-level pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials (the Randomized Evaluation of PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events [REPLACE-2]; Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY [ACUITY]; and Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction [HORIZONS-AMI]) including 14,784 patients (25.6% were women), bivalirudin was compared with UFH plus GPI in ACS patients undergoing PCI. Compared with males, females were associated with higher 30-day bleeding events which in turn emerged as being the strongest independent predictor of one-year mortality rather than gender per se. Additionally, both sexes experienced similar safety benefits of bivalirudin in reducing bleeding complications, but women experienced a more pronounced benefit of bivalirudin in reducing one-year mortality than men10. Importantly, these results come from trials in which UFH was administered with routine use of GPI, there was no use of newer antiplatelet agents, and PCI procedures were almost exclusively performed by the femoral access. In the sex-based analysis of BRIGHT, a trial comparing bivalirudin versus heparin versus heparin plus tirofiban in acute MI patients undergoing PCI, female patients receiving bivalirudin were associated with significantly lower rates of 30-day bleeding and NACE, but no differences in terms of mortality, ST or MACE11. In the sex-based analysis of the ISAR-REACT 4 trial, where patients with NSTEMI (n=1,721; 399 women, 23.2%) were randomly allocated to receive bivalirudin or heparin plus abciximab, there were no between-group differences in the main outcome (30-day composite of death, large recurrent MI, urgent TVR or major bleeding), but bivalirudin reduced major bleeding in both male and female patients12.

Our current results are entirely consistent with previous evidence, indicating that bivalirudin provides a consistent effect in both sexes, resulting in lower risks of bleeding complications across many of the available RCTs. Additionally, in MATRIX, we found that reduction of bleeding, mainly the most severe episodes, was irrespective of GPI use12. Interestingly, however, in the context of the recently reported VALIDATE-SWEDEHEART trial, where bivalirudin did not reduce the primary composite endpoint of NACE or clinically relevant bleeding at six months after intervention as compared to UFH alone, there was a signal of heterogeneity across sexes (pint=0.05), with female patients apparently deriving a greater benefit from treatment as compared to males2. Therefore, in summary, current evidence shows either a consistent or perhaps a slightly greater treatment effect in female patients treated with bivalirudin as compared to UFH, a finding which seems to be justifiable by prior observations that females are at increased risk for periprocedural bleeding occurrences.

The inconsistent effect of bivalirudin on the NACE endpoint probably reflects differences in study design, choice of the comparator arm, patient selection and endpoint definitions across available studies. Similarly, the effect of bivalirudin on mortality has been inconsistently observed across trials and some registry data13, which may reflect the fact that this effect, if real, may be small, and probably confounded by the baseline risk status of patients and concomitant treatment and medications.

Prior observations that the use of bivalirudin increases the risk of acute ST have prompted investigations to mitigate that risk by prolonging bivalirudin infusion after PCI14,15. Overall, the MATRIX Treatment Duration study found that post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin did not result in lower rates of the primary endpoint or definite ST at 30 days than with no post-PCI infusion. This latter finding was also confirmed in the present analysis in both male and female patients.

In current practice, when deciding on the anticoagulation strategy to adopt in ACS patients undergoing PCI, it should also be borne in mind that bivalirudin remains much more expensive than UFH; however, updated cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted.

Limitations

Although this is a pre-specified subgroup analysis, the MATRIX Antithrombin and Treatment Duration trials were not powered to explore differences between sexes; randomisation was not stratified by sex. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, increasing the risk of type I error. The protocol allowed discretionary use of GPI in the heparin group and two different infusion regimens in the post-PCI bivalirudin infusion group. Although this is consistent with clinical practice, it makes the study results more difficult to interpret.

Conclusions

Among male and female patients with ACS undergoing invasive treatment, neither the rate of MACE nor the rate of NACE was significantly lower with bivalirudin than with unfractionated heparin and discretionary use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. In both sexes, the post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin for at least four hours after the intervention did not result in a lower rate of the composite outcome of ischaemic and bleeding events, including stent thrombosis, than with no post-PCI infusion. Our observations of lower risks of bleeding and especially of fatality rates in both male and female patients undergoing invasive management should be interpreted in the context of the available evidence, which suggests a rather consistent and inconsistent treatment effect of bivalirudin on bleeding and fatal endpoints, respectively, both in males and females.

|

Impact on daily practice Current data show that neither male nor female patients gained significant benefit in terms of composite endpoints by receiving bivalirudin compared with heparin with discretionary use of GPI, although a lower rate of bleeding was observed. Also, the post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin was not superior to no infusion in both sexes. |

Appendix. Authors’ affiliations

1. Department of Cardiology, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland; 2. Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Federico II University of Naples, Naples, Italy; 3. Institute of Primary Health Care (BIHAM), Bern University, Bern, Switzerland; 4. Applied Health Research Centre, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St Michael’s Hospital, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; 5. Ospedale Pasquinucci, Massa, Italy; 6. San Camillo-Forlanini, Rome, Italy; 7. Ospedale Sacra Famiglia Fatebenefratelli, Erba, Como, Italy; 8. Città di Lecce Hospital, Lecce, Italy; 9. Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy; 10. A.O. Civili Riuniti, Giovanni Paolo II, Sciacca, Italy; 11. Ospedale San Jacopo, Pistoia, Italy; 12. Thoraxcenter, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; 13. Azienda Ospedali Riuniti-Presidio GM Lancisi, Ancona, Italy; 14. Ospedale San Giuseppe Moscati, Avellino, Italy; 15. Ospedale Maggiore, Lodi, Italy; 16. Università degli Studi G. d’Annunzio Chieti e Pescara, Chieti, Italy; 17. A.O.U. San Giovanni Battista Molinette di Torino, Turin, Italy; 18. Department of Cardio-Thoracic and Vascular Diseases, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy; 19. Ospedale Civile di Mirano, Mirano, Italy; 20. Ospedali Riuniti Padova Sud, Monselice, Italy; 21. University Hospital Clinic, IDIBAPS (Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer), Barcelona, Spain; 22. A.O.U. San Luigi Gonzaga di Orbassano, Turin, Italy; 23. Ospedale San Francesco, Nuoro, Italy; 24. Azienda U.S.L. Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy; 25. Ospedali Riuniti ASL 17, Savigliano, Italy; 26. Ospedale San Donato, Arezzo, Italy; 27. AORN Cardarelli, Naples, Italy; 28. Maastricht University Medical Center, and Zuyderland MC, Maastricht, the Netherlands; 29. Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Sweden; 30. A.O. Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy; 31. Hospital Marques de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain; 32. IRCCS Multimedica, Sesto San Giovanni, Milan, Italy; 33. Ospedale Santo Spirito in Saxia, Rome, Italy

Funding

The trial was sponsored by the Società Italiana di Cardiologia Invasiva (GISE, a non-profit organisation), which received grant support from The Medicines Company and Terumo. This substudy did not receive any direct or indirect funding.

Conflict of interest statement

G. Gargiulo reports research grant support from the Cardiopath PhD programme. M. Zimarino reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. G. Casu reports personal fees from Boston Scientific and Bayer SpA, outside the submitted work. V. Guiducci reports personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. F. Liistro reports personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. J.M. de la Torre Hernandez reports unrestricted grants from Boston Scientific and Abbott and being on the advisory panel for Medtronic, Boston Scientific and Abbott, outside the submitted work. A. van ‘t Hof reports grants and personal fees from The Medicines Company, during the conduct of the study, grants from Medtronic, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, and grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, outside the submitted work. E. Omerovic reports personal fees for advisory board work from Boston Scientific and Bayer, and an institutional grant from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. S. Windecker reports research contracts to the institution from Amgen, Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude Medical, outside the submitted work. M. Valgimigli reports grants from The Medicines Company and Terumo, during the study, grants from AstraZeneca, and personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, and Bayer, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.