The issue of the optimal antithrombotic therapy following a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or an acute coronary syndrome has remained a question in modern cardiology, despite many successive breakthroughs. Nearly two decades ago, the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial demonstrated the superiority of dual antiplatelet therapy, based on aspirin with a P2Y12 inhibitor over aspirin and placebo, in this high-risk population1. Since then, numerous trials have evaluated various strategies of more or less prolonged DAPT duration with more or less potent P2Y12 inhibitors in association with aspirin2. Such strategies have resulted in lowering acute coronary events, albeit at the cost of an increased risk of bleeding and with an overall uncertain impact on all-cause mortality. All these trials shared a common and potential limiting factor: P2Y12 inhibitors were used on top of aspirin. Such a strategy was justified by the fact that aspirin, the most ancient antiplatelet agent available, has long been known to reduce events in cardiovascular disease3.

However, several arguments have recently been raised to challenge the role of aspirin as the gold standard for background antithrombotic therapy in these patients4. First, aspirin has been associated with an increased risk of severe bleeding, notably of intracranial or gastrointestinal haemorrhages in particular in case of association with P2Y12 inhibitors4. In fact, the cyclooxygenase inhibition associated with aspirin leads to a reduction of mucosal levels of prostaglandins, thus exposing the gastrointestinal tract to acid-related lesions and ulcers. Second, an in vitro study reported that aspirin provides only little additional inhibition of platelet aggregation when associated to strong P2Y12 receptor blockade, thus challenging the biological rationale behind prolonged DAPT5. Finally, one may recognise that the ischaemic risk, to which patients undergoing contemporary PCI remain exposed, is no longer the same as in the CURE trial. Use of newer-generation drug-eluting stents has resulted in lower rates of target lesion revascularisation or stent thrombosis, compared to bare metal and first-generation drug-eluting stents, even when associated with shorter DAPT treatment duration6. The generalisation of intensive lipid-lowering treatment may also result in lowering the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction (MI) or coronary revascularisation7. Altogether, these arguments have led to a paradigm change with the proposition of aspirin-free strategies for secondary prevention of coronary events4.

The What is the optimal antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing (WOEST) trial was the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the early discontinuation of aspirin with clopidogrel monotherapy, compared to DAPT, in patients treated with vitamin K antagonists4. The GLOBAL LEADERS was the first, and remains the largest RCT to date, to evaluate an early discontinuation of aspirin, one month after the index PCI, with ticagrelor continuation in an all-comer population without indication for chronic oral anticoagulation8. The trial did not find the experimental strategy to be associated with a significant reduction of the primary endpoint, a composite of all-cause death and adjudicated new Q-wave MI at two years, compared to prolonged DAPT duration, although its rate was numerically lower with the former strategy (rate ratio 0.87, 95% CI: 0.75-1.01). In this issue of EuroIntervention, Serruys and co-authors present the results of a substudy detailing the rates of site-reported Academic Research Consortium (ARC)-2 defined patient-oriented composite endpoints (POCE – all-cause death, stroke, MI, or any revascularisation) and net adverse clinical events (NACE – POCE or bleeding type 3 or 5 according to the Bleeding ARC)9.

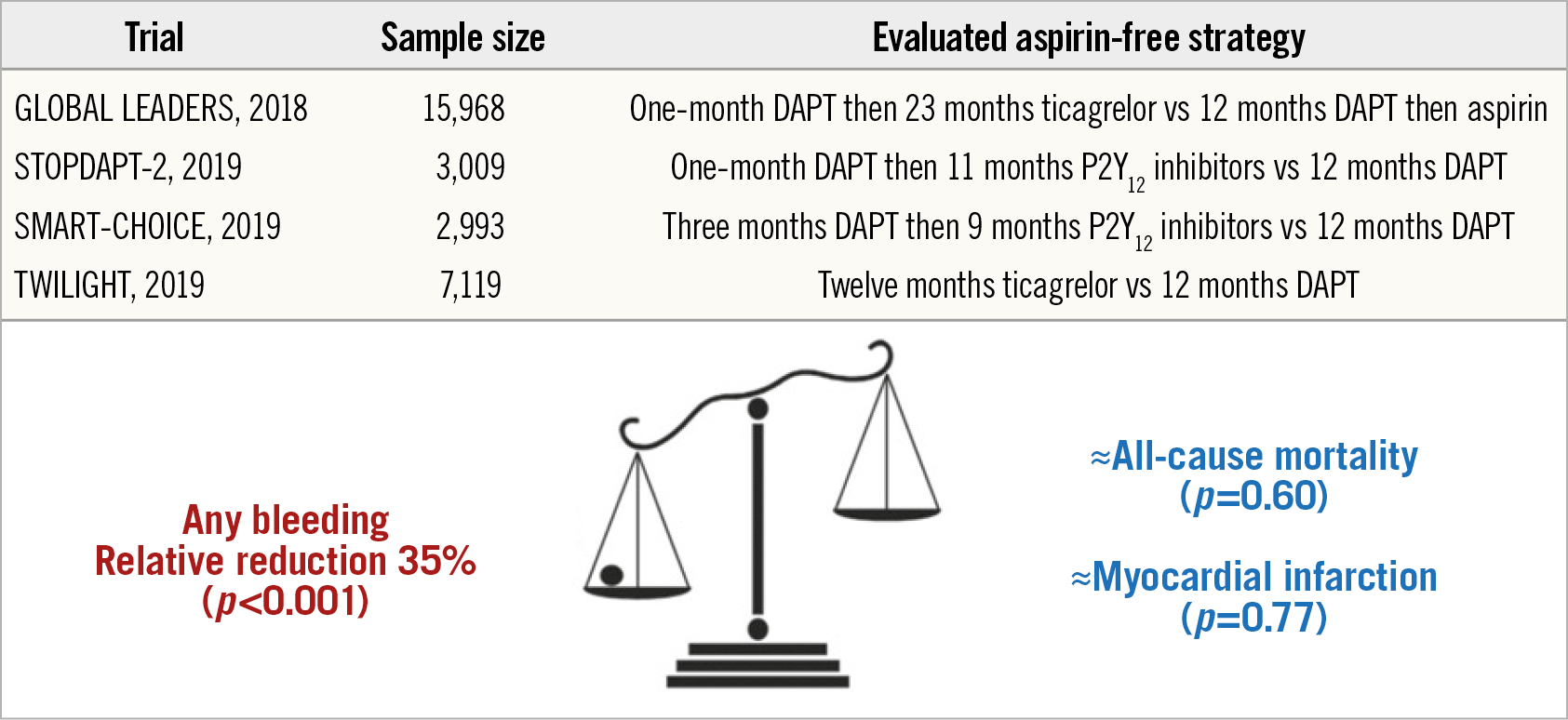

These endpoints, not reported in the main analysis, allow a more detailed and complete interpretation of the impact of early aspirin discontinuation with ticagrelor prolongation. Although these endpoints were site-reported, they remain of interest and should not be overlooked only because of the lack of central adjudication, as skilfully demonstrated by the authors. Consistent with the main results of the GLOBAL LEADERS trial, the experimental strategy was associated with numerically lower rates of POCE and NACE, albeit not reaching statistical significance (13.2% vs 14.2%, HR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.85-1.01 and 14.4% vs 15.5%, HR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.85-1.00, respectively). The authors rightfully conclude that the experimental strategy of one-month DAPT followed by 23 months of ticagrelor alone did not result in a significant reduction of site-reported POCE and NACE. Does this mean that an aspirin-free strategy is not useful in patients undergoing PCI? Not if you look at the bigger picture and consider the accumulation of recent evidence. Indeed, although the trends observed in the GLOBAL LEADERS trial were never statistically significant, no safety signal was reported with early aspirin discontinuation and ticagrelor therapy prolonged. Since its publication, three large RCTs including patients without indication for chronic oral anticoagulation undergoing PCI have reported lower rates of bleeding complications associated with aspirin-free strategies and P2Y12 inhibitor prolongations without any significant offset with respect to ischaemic events (Figure 1),10. These trials enrolled patients with various risk profiles, including high ischaemic risk patients in the Ticagrelor With Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients After Coronary Intervention (TWILIGHT) study10. Although future trials are warranted to determine the optimal choice for P2Y12 inhibitor, duration of DAPT prior to aspirin discontinuation, and the population to be treated, these results are reassuring and encouraging for aspirin-free strategies with P2Y12 inhibitor single therapy following PCI in patients without an indication for chronic oral anticoagulation. Of note, these results do not preclude the use of aspirin for long-term secondary prevention in patients with chronic and stable coronary artery disease, particularly in association with a lower dose of ticagrelor or rivaroxaban2. Altogether, various sound combinations of antithrombotic treatments for secondary prevention exist and should be used according to the patient’s specificities and timeline from the index event, with an emphasis on safety and bleeding prevention within the first year and on efficacy and ischaemic event reduction thereafter.

Figure 1. Pooled analysis of randomised controlled trials evaluating aspirin-free strategies in patients undergoing PCI. CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Conflict of interest statement

G. Montalescot reports the following during the past two years: research grants to the institution or consulting/lecture fees from ADIR, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin Chimie AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical, Brigham Women’s Hospital, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Celladon, CME Resources, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Europa, Elsevier, Fédération Française de Cardiologie, Fondazione Anna Maria Sechi per il Cuore, Gilead, ICAN, Janssen, Lead-Up, Menarini, Medtronic, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, The Medicines Company, TIMI Study Group, and WebMD. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.