Abstract

In 2017, two focused updates from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) set new standards for the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): six months for patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and 12 months for patients with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS)1. Special considerations were added for candidates to DAPT prolongation (i.e., >12 months) and candidates to DAPT shortening (i.e., one to three months)1. While the former include patients identified based on criteria of baseline risk and procedural complexity, the latter include an emerging and sizeable subgroup of patients at high bleeding risk (HBR), for which standardised definitions have recently been issued by the Academic Research Consortium2.

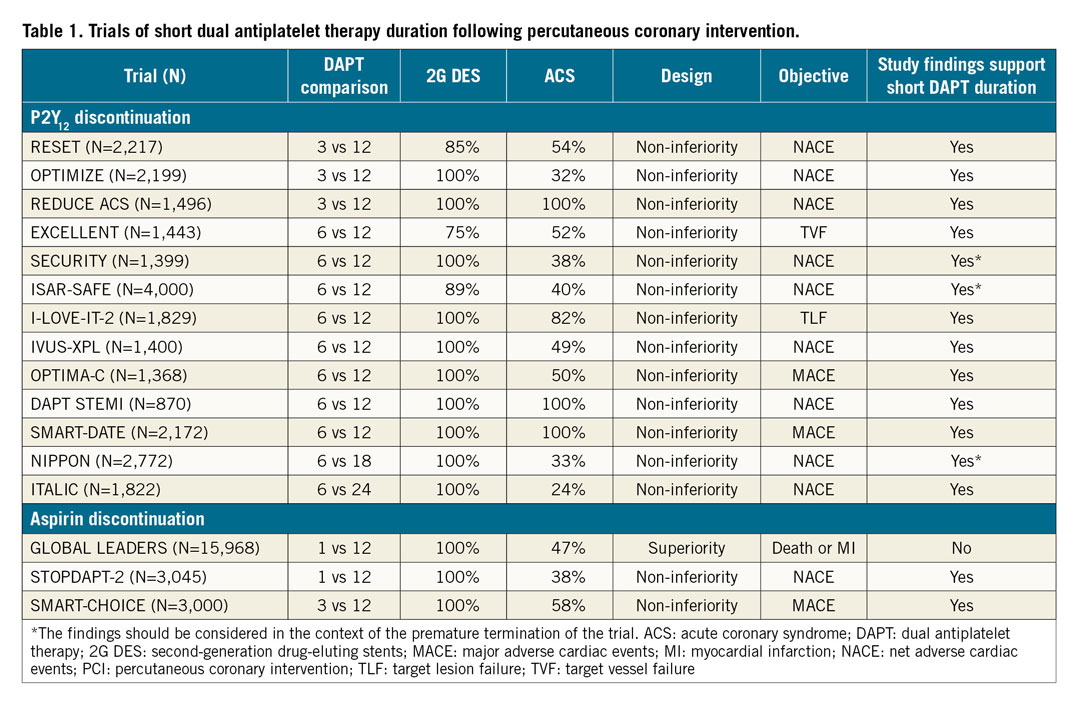

Current indications on DAPT duration after PCI stem from the results of several DAPT studies published over the course of approximately 20 years3. In the investigational arms of the 13 available trials of short DAPT (Table 1), the P2Y12 inhibitor –generally clopidogrel– was stopped at three or six months. These trials mostly included low-risk PCI patients with stable CAD, while three trials included only patients with ACS. Of note, in one of these ACS trials, shortening DAPT duration resulted in a catch-up in myocardial infarction (MI)4. In all DAPT duration studies, a non-inferiority design was selected, introducing some challenges in their interpretation. For example, the lower than anticipated event rate and/or the premature interruption of some of the studies possibly biased their results towards non-inferiority. In some cases, the use of a net benefit primary endpoint also confounded the interpretation because DAPT acts differentially on ischaemic and bleeding endpoints. These limitations notwithstanding, trials of short DAPT collectively suggest that three to six months of DAPT is probably enough in low-risk PCI patients, a meaningful information that led to redefining DAPT standards in the way mentioned above1.

In 2019, when speaking of “short DAPT”, we may now enter a problem of semantics. For years, this jargon has been intended to mean the early discontinuation of the P2Y12 inhibitor with continuation of aspirin lifelong. However, DAPT remains conceptually short even if aspirin is discontinued early and the P2Y12 inhibitor is maintained. There is some theoretical rationale for a strategy of dropping aspirin rather than the P2Y12 inhibitor5. For example, aspirin is known to increase bleeding complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding and intracranial haemorrhage6. In secondary prevention, this effect is amply counterbalanced by the benefit in reducing thrombotic complications7, but trials and meta-analyses supporting this concept were performed when other pharmacological strategies for secondary prevention (e.g., statins) were not widely available or implemented. Also importantly, the availability of potent P2Y12 inhibitors such as prasugrel and ticagrelor may justify revisiting the concept of aspirin as the cornerstone of DAPT5.

In perspective, we should acknowledge that most trials of new antithrombotic compounds across disparate clinical scenarios were performed on a background of aspirin therapy. Therefore, when discussing the merits of aspirin versus P2Y12 inhibitors we should look at a particular set of studies where these strategies were compared vis-à-vis. This occurred in the large CAPRIE trial, published in 1996 and including 19,185 patients with recent stroke, recent MI or symptomatic peripheral artery disease, where clopidogrel decreased the composite of death, MI or stroke and was associated with less gastrointestinal bleeding compared with aspirin8. In the earlier TASS trial, published in 1989 and including 3,069 patients at increased risk of stroke, ticlopidine was also found to decrease the composite of death or stroke, and had less gastrointestinal bleeding compared with aspirin at a higher dose than normally accepted today (1,300 mg)9. SOCRATES, a more contemporary trial of ticagrelor versus a low dose of aspirin in 13,199 patients with acute stroke or transient ischaemic attack, found no difference in death, MI and stroke or in bleeding, but ticagrelor reduced stroke, an important secondary endpoint10.

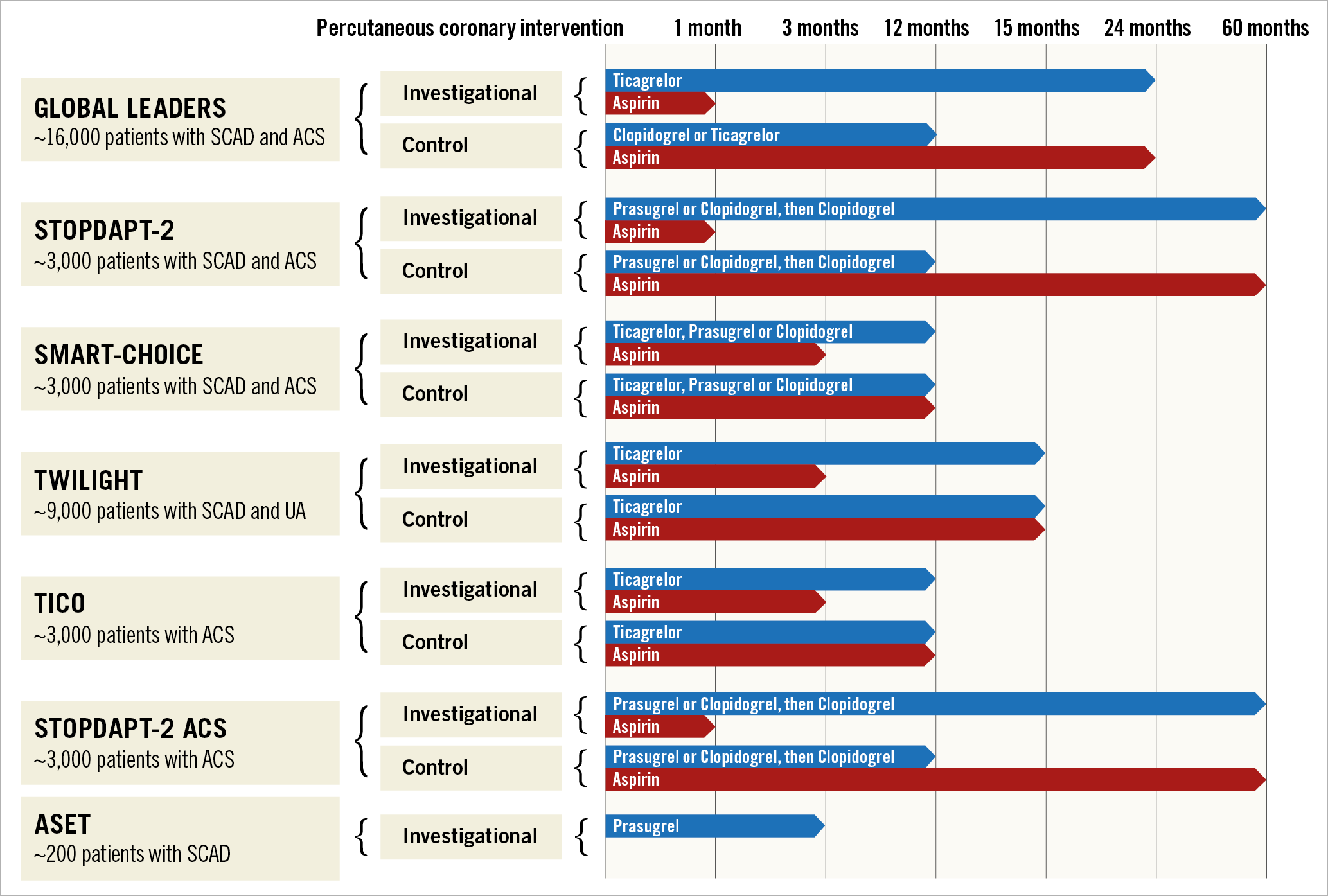

Starting from 2013, a new series of studies is now investigating aspirin-free strategies in the field of PCI5. In a way, these are simply studies of short DAPT followed by single antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor. It is no surprise that the first trials where this strategy was attempted included orally anticoagulated patients, who are HBR by definition2. A meta-analysis of about 10,000 patients from WOEST, PIONEER-AF PCI, RE-DUAL PCI and AUGUSTUS recently showed that abandoning aspirin upfront or early after PCI results in reduced bleeding with no significant penalty in terms of ischaemic protection11. The question now becomes whether renouncing aspirin early (i.e., shortening DAPT) is somehow beneficial and/or not detrimental in non-anticoagulated patients at lower risk of bleeding undergoing PCI (Figure 1). Indeed, we already know that low-risk patients who receive contemporary stent technologies do not need prolonged DAPT to avoid stent thrombosis, but is dropping aspirin the same as dropping a P2Y12 inhibitor? One argument that is reasonably raised by advocates of maintaining aspirin in preference to clopidogrel is that P2Y12 inhibitors are not immune from a certain degree of interindividual variability in platelet inhibition12. Therefore, keeping patients on chronic clopidogrel only could expose those who are clopidogrel-resistant to the risk of not being protected at all. The abovementioned CAPRIE trial partly addresses these concerns, suggesting that the larger proportions of high on-treatment platelet resistance noted in pharmacodynamic studies of clopidogrel did not translate into significant incremental risk on the ground of a large-scale clinical evaluation8. If anything, this variability could be addressed by the use of other P2Y12 inhibitors, such as prasugrel or ticagrelor.

Figure 1. Study design of trials of short dual antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; SCAD: stable coronary artery disease; UA: unstable angina

Studies of short DAPT with aspirin discontinuation have produced controversial results so far (Table 1). The GLOBAL LEADERS trial investigated ticagrelor monotherapy after aspirin discontinuation at one month13. With a p-value of 0.07 for the primary endpoint of death or MI, one may discuss several reasons why the trial fell short of its primary objective, including the dilutive effect of the neutral head-to-head comparison between ticagrelor and aspirin occurring by protocol in the landmark between 12 and 24 months, and the high rates of ticagrelor discontinuation in the experimental arm. Yet, GLOBAL LEADERS remains a generator of good hypotheses. Recently, two Asian studies of short DAPT and aspirin-free strategies were published, with more positive findings1415. In the STOPDAPT-2 and SMART-CHOICE trials, aspirin discontinuation occurred at one and three months, respectively. Both trials were designed to assess non-inferiority and met their primary objective. Limitations of small non-inferiority trials of short DAPT also apply to these cases, and the external validity of the study findings should be considered in the context of the low-risk populations included and the wide use of intracoronary imaging to optimise the results of PCI. In aggregate, if three pieces of evidence constitute proof, then GLOBAL LEADERS, STOPDAPT-2 and SMART-CHOICE collectively suggest that the aspirin-free hypothesis is valid and worthy of additional investigation.

Moving forward, the next stop is TWILIGHT, a blinded trial of aspirin versus placebo in patients undergoing complex PCI on DAPT with ticagrelor for three months (Figure 1)16; in other words another trial of short DAPT, designed to demonstrate that ticagrelor monotherapy reduces bleeding as compared with DAPT. A similar study, called TICO, is underway in South Korea. STOPDAPT-2 ACS is also ongoing in Japan with the intended goal of reproducing the positive findings of STOPDAPT-2 in patients with ACS. It is of note that all the trials mentioned so far are trials of “short DAPT” but they are not trials of “no DAPT”. In fact, renouncing the established benefit of DAPT in the very early and most vulnerable phase of PCI and/or an ACS has been considered too risky by the study investigators or the institutional review boards for patients included in such investigations. In this issue of EuroIntervention we publish the rationale of ASET, a proof-of-concept trial that brings the concept of “short DAPT” to the next level. Patients with stable CAD or stabilised ACS will receive prasugrel alone from the day after the procedure17.

Designed as an exploratory trial, ASET will be interrupted according to pre-specified stopping rules if more than three stent thromboses occur during recruitment. With its provocative design (and title, “Acetyl-salicylic Elimination Trial”), ASET aims to open the final chapter in the decennial history of DAPT for PCI.