Current guidelines recommend a minimum of 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor following an acute coronary syndrome (ACS)1. Furthermore, the extension of DAPT therapy beyond 12 months has been demonstrated to reduce cardiovascular events at the cost of increased bleeding2. Due to the elevated ischaemic risk in ACS patients, the benefit of extended DAPT duration appears to be more favourable in ACS patients compared to stable coronary syndromes3. Whether newer stent designs could lower ischaemic risk sufficiently to tip the scales in favour of shorter DAPT durations remains uncertain.

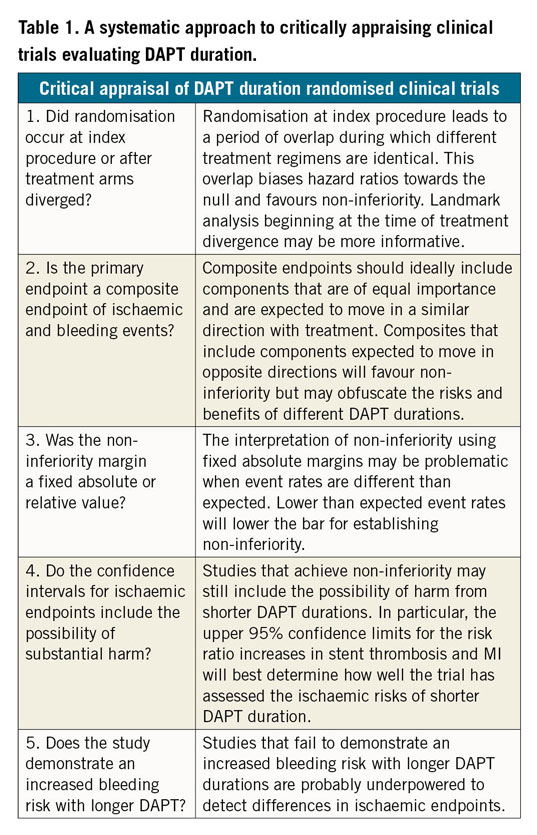

Critical appraisal of recent trials seeking to evaluate abbreviated DAPT duration among ACS patients treated with newer stents is paramount (Table 1). The SMART-DATE trial compared 12 months or longer of DAPT to six months in ACS patients, and met statistical non-inferiority in the primary composite ischaemic endpoint but observed an increase in myocardial infarction (MI) with abbreviated DAPT4. The DAPT-STEMI trial compared six versus 12 months of DAPT in patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and demonstrated non-inferiority in the composite bleeding and ischaemic endpoints5. It was relatively underpowered to examine ischaemic endpoints alone. The generalisability of these trials is complicated by the heterogeneity in patient and procedural characteristics.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, De Luca et al present the results of the REDUCE trial, a prospective, open label, multicentre study of 1,496 ACS patients randomised during their index hospitalisation to three or 12 months of DAPT6.

Similar to several prior non-inferiority studies testing short DAPT durations, the trial used a composite endpoint that combined both ischaemic and bleeding events, two inversely related outcomes, to meet a wide non-inferiority margin. Although non-inferiority was technically achieved, the authors rightly exercised caution in their interpretation of the results. The treatment arms had equivalent treatment regimens for the first three months after randomisation, and the primary endpoint was heavily influenced by target vessel revascularisation – an endpoint not expected to differ based on DAPT duration. Both of these factors further lowered the already low bar to achieve non-inferiority.

More concerning were the safety signals that appeared to emerge in the trial. The three-month DAPT group had twice the rate of stent thrombosis and a 60% higher cardiac mortality rate at one year. The landmark analyses beginning at three months clearly show these events beginning to diverge after discontinuation of DAPT in the short duration group. Similar signals of harm observed in the SMART-DATE trial should give clinicians pause for thought before entertaining an abbreviated DAPT regimen in ACS patients.

These safety signals should not be seen as a surprise. The occurrence of ACS should be seen as identifying a high-risk patient, and not just a high-risk lesion. In the DAPT study, the largest placebo controlled randomised trial of DAPT duration conducted to date, the reduction in MI from long-term DAPT therapy was driven as much through reducing MIs in non-stented regions as through reducing stent-related events2. The development of more potent P2Y12 inhibitors only potentiates the secondary benefits of DAPT which, in turn, may favour longer DAPT duration, especially given the prothrombotic substrate of ACS patients. There is no free lunch to be gained through shorter DAPT durations – one must be prepared to accept higher ischaemic events with shortened DAPT duration.

These ischaemic implications must be weighed against bleeding risk. REDUCE, like other shorter DAPT duration trials, failed to demonstrate an expected significantly higher bleeding risk with longer DAPT4,5. This highlights either the underpowered nature of these trials or the overall low incidence of both bleeding and ischaemic events in trial-enrolled patients that questions the studies’ ability to detect a signal for harm. Importantly, those patients at highest risk of bleeding who may derive the greatest benefit from shorter DAPT were excluded from this and other studies.

Collectively, De Luca et al add to the growing evidence base that DAPT duration should be guided by an individualised assessment of risk. The DAPT score is one example of a clinical tool that integrates patient and procedural characteristics to provide an uncoupled assessment of both bleeding and ischaemic risk, especially among ACS patients7,8. The question remains if it, or another similarly derived risk stratification tool, could help to identify those patients in whom less intensive antiplatelet regimens may be favoured.

Despite advances in stent technology and antiplatelet agents, the current data evaluating shorter DAPT durations are not reassuring. Some subsets of patients at particularly high risk of bleeding in excess of the ischaemic risk may benefit from shorter or less intensive DAPT regimens. Until adequately powered randomised controlled trials demonstrate a clinically meaningful identification of those patients, we should continue to adhere to the current guideline-recommended 12-month minimum DAPT duration following ACS.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Yeh has served on scientific advisory boards, consulted for, and received research support from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. He also receives funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01HL136708) and the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. N. Mihatov has no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.