Abstract

Background: For patients with high bleeding risk, the BioFreedom stent is safer and more effective than a bare metal stent. However, at the one-year follow-up of the SORT OUT IX trial, the BioFreedom stent did not meet the criteria for non-inferiority for target lesion failure (TLF) when compared with the Orsiro stent and had a higher incidence of target lesion revascularisation (TLR).

Aims: The aim of the study was to compare the two-year outcomes following coronary implantation of the BioFreedom or the Orsiro stents in all-comer patients.

Methods: The Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials with Clinical Outcome (SORT OUT) IX trial is a prospective, multicentre, randomised clinical trial comparing the BioFreedom and the Orsiro stents. The primary endpoint, TLF, was a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI; not related to other lesions) and TLR.

Results: A total of 1,572 patients were randomised to treatment with the BioFreedom stent and 1,579 patients with the Orsiro stent. At two-year follow-up, TLF was 7.8% in the BioFreedom and 6.3% in the Orsiro stent groups (rate ratio [RR] 1.23, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.94-1.61). Risks of cardiac death, MI and definite stent thrombosis did not differ significantly between the groups, whereas more patients in the BioFreedom group had TLR (5.1% vs 2.6%; RR 1.98, 95% CI: 1.26-2.89) attributable to a higher risk of TLR within the first year (3.5% vs 1.3%; RR 2.77, 95% CI: 1.66-4.62).

Conclusions: At two years, there were no significant differences between the BioFreedom and Orsiro stents for TLF. TLR was significantly higher with the BioFreedom stent due to higher risk of TLR within the first year.

Introduction

The persistence of late events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with both first-generation and second-generation permanent polymer drug-eluting stents (DES) has motivated the development of new stent designs with thinner stent struts, biodegradable polymers, or more biocompatible polymers1. A cobalt-chromium, third-generation, sirolimus-eluting Orsiro (Biotronik) stent combines both ultrathin stent struts and biodegradable polymer technology. It demonstrated a similar five-year risk of target lesion failure (TLF) compared with the second-generation permanent polymer everolimus-eluting stent2. The “Safety and Effectiveness of the Orsiro Sirolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System in Subjects With Coronary Artery Lesions (BIOFLOW-V)” randomised trial even demonstrated the superiority of the Orsiro stent compared to the everolimus-eluting stent, which persisted through two and three years of follow-up345.

The complete absence of potential inflammatory stimuli from polymer coatings has been attempted with the development of non-polymeric drug-coated stents6. The BioFreedom stent (Biosensors Europe) is a stainless-steel polymer-free DES with an abluminal surface that has microstructure modifications that allow the adhesion and controlled release of the highly lipophilic antiproliferative agent, biolimus7. This newer device has been compared with bare metal stents and first- and second-generation permanent polymer DES. It was found to be superior to bare metal stents in patients with high bleeding risk and non-inferior to a first- and second-generation DES8910.

The "BIOFREEDOM Stent Versus ORSIRO Stent: SORT OUT IX” trial was the first study to demonstrate that the BioFreedom stent is not non-inferior to a modern DES in a population-based all-comers setting at 12 months of follow-up11. The present analysis reports two-year clinical outcomes of the SORT OUT IX trial.

Methods

Patients and study design

SORT OUT IX is a randomised, multicentre, single-blind, all-comer, two-arm, blinded endpoint, non-inferiority trial comparing the BioFreedom to the Orsiro stent in the treatment of atherosclerotic coronary artery lesions. A detailed study protocol was provided in the primary publication11.

Patients were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, had chronic stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome, and had at least one coronary lesion with >50% diameter stenosis, requiring treatment with a DES. If multiple lesions were treated, the allocated study stent had to be used in all lesions. Exclusion criteria were life expectancy of <1 year; an allergy to aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, prasugrel, sirolimus, or biolimus; participation in another randomised stent trial; or an inability to provide written informed consent. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics for Southern Denmark (S-20150132) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (15/47707). All patients provided written informed consent for trial participation before randomisation. Randomisation, study stents and use of antithrombotic medication are described in the primary publication11.

Outcome measures

Definitions of the endpoints were provided in the main publication11. The primary endpoint, TLF, is a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI) only related to the index lesion or target lesion revascularisation (TLR) with PCI or coronary artery bypass operation within 12 months. Individual components of the primary endpoint comprise the secondary endpoints: cardiac death; MI; clinically indicated TLR; all death (cardiac and non-cardiac) and target vessel revascularisation; definite, probable, possible, and overall stent thrombosis according to the Academic Research Consortium definition12; and a patient-related composite endpoint (all death, all MI, or any revascularisation).

Clinical event detection

Dedicated follow-up was not scheduled, but clinical events were recorded based on patients’ admittance to the health care system for self-reported angina or equivalent symptoms. Data on mortality, hospital admission, coronary angiography, repeat PCI, and coronary artery bypass operation were obtained from the following national Danish administrative and healthcare registries: the Civil Registration System13; the Western Denmark Heart Registry1415; and the Danish National Registry of Patients16, the latter which maintains records on all hospitalisations in Denmark. The Danish National Health Service provides universal tax-supported health care, guaranteeing residents free access to general practitioners and hospitals. The Danish Civil Registration System has kept electronic records on sex, birth date, residence, emigration date, and vital status changes since 196813, with daily updates; the 10-digit civil registration number assigned at birth and used in all registries allows accurate record linkage. Loss to follow-up was minimised in the study, as vital status data for our study participants was provided by the Civil Registration System. The National Registry of Causes of Deaths and the Danish National Registry of Patients provided information on causes of death and diagnoses assigned by the treating physician during hospitalisations (coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10]16). An independent event committee, blinded to study stent type assignment during the adjudication process, reviewed all endpoints and source documents to adjudicate causes of death, reasons for hospital admission, and diagnosis of MI. Two dedicated PCI operators at each participating centre independently reviewed cine films for the event committee to classify stent thrombosis, TLR and target vessel revascularisation (either with PCI or coronary artery bypass operation).

Statistical analysis

We compared distributions of categorical variables using the chi-square test. For the analysis of every endpoint, follow-up continued until the date of an endpoint event, death, or until two years after stent implantation or emigration, whichever came first. Survival curves were constructed based on time to events, accounting for the competing risk of death (in cases where death was not included in the outcome). In the presence of competing risk, the Kaplan–Meier estimator that treats the competing events as independent censoring is an upward biased estimate of the cumulative incidence function. Patients who received the Orsiro stent were used as the reference group. Rate ratios (RR) were calculated for TLF at two-year follow-up and for pre-specified patient subgroups (based on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics). In all analyses, the intention-to-treat principle was used. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.4). This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02623140.

Results

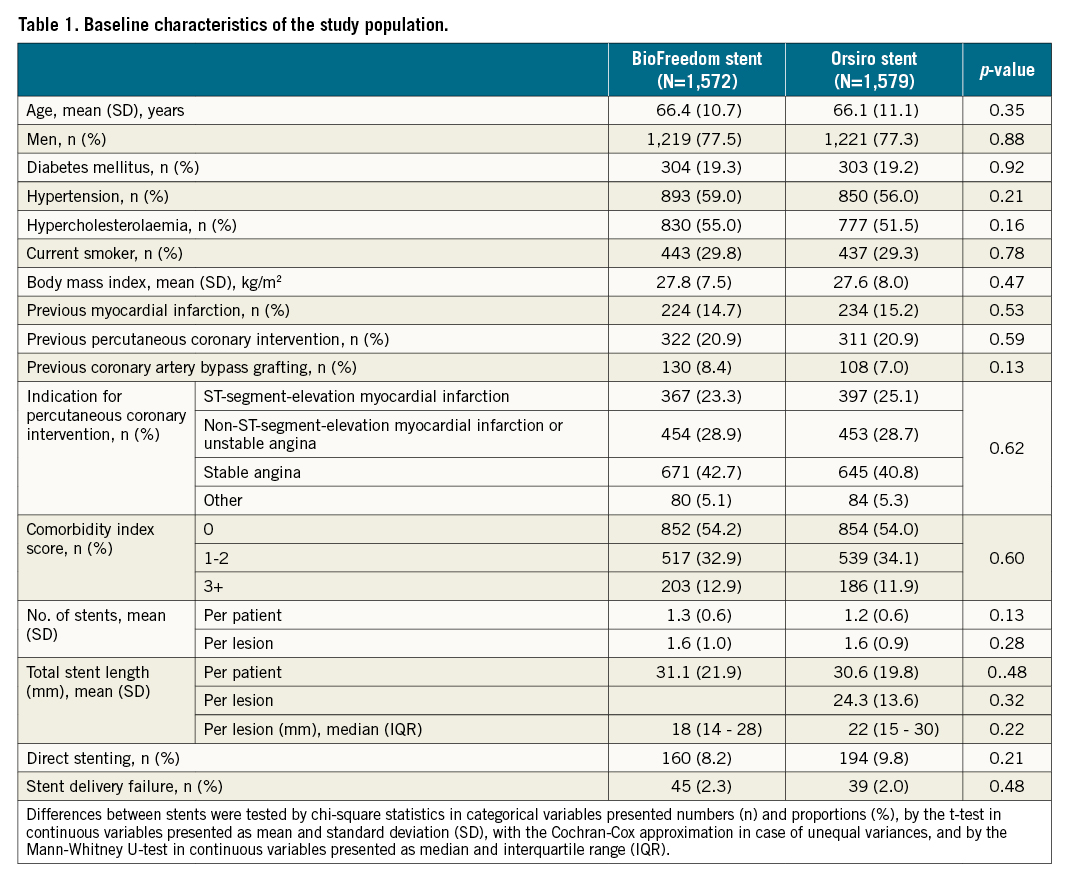

Between December 2015 and April 2017, 3,151 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive either the BioFreedom stent (1,572 patients [1,966 lesions]) or an Orsiro stent (1,579 patients [1,985 lesions]). Five patients were censored due to emigration but no patients were lost to follow-up. Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between the two stent groups and are summarised in Table 1.

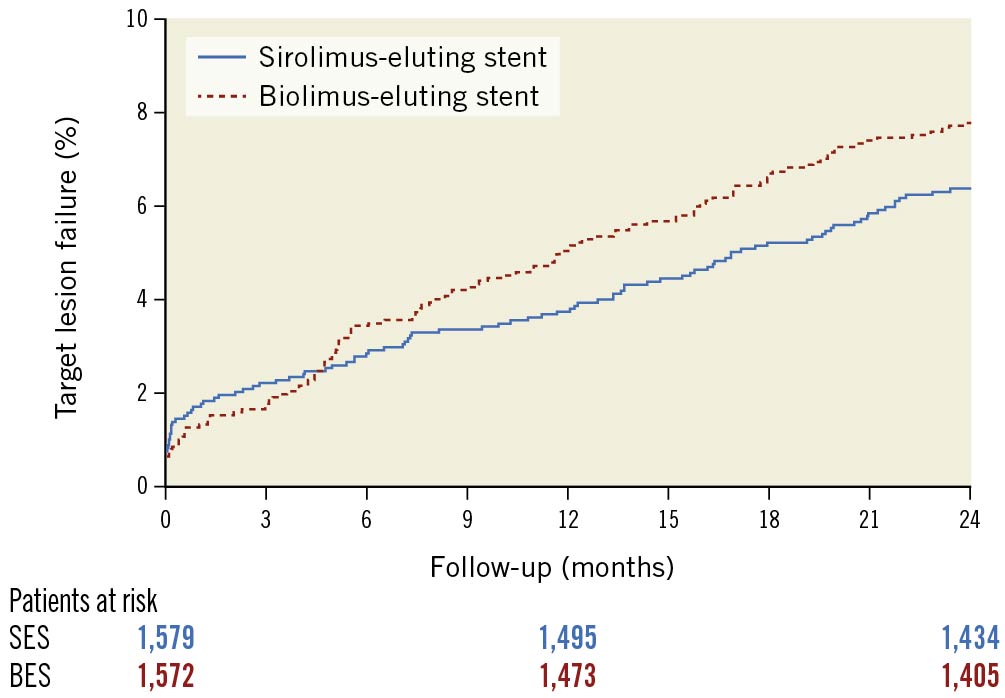

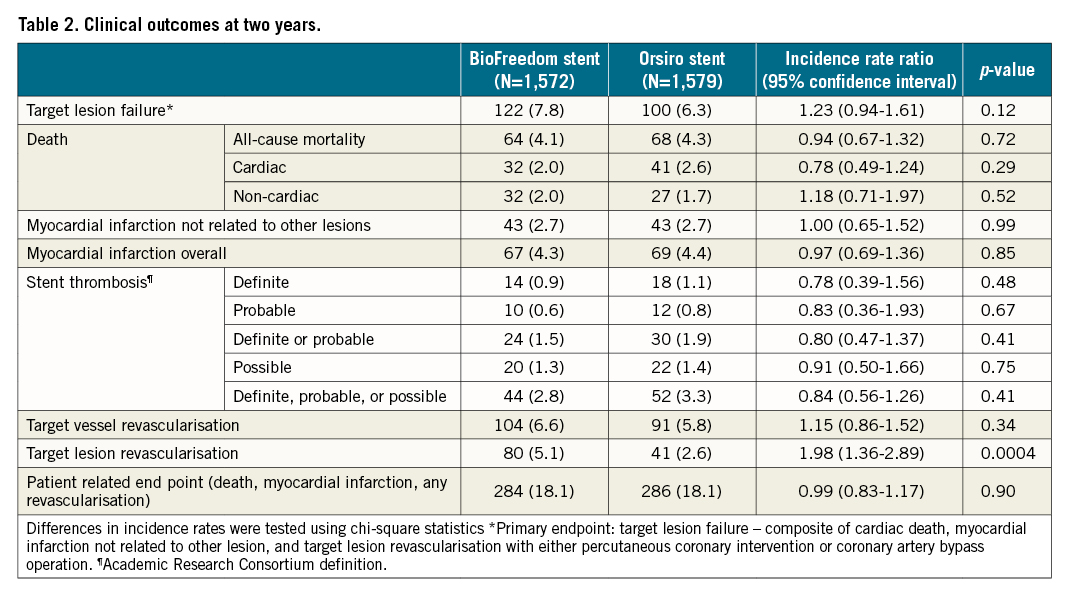

At two years, the composite endpoint TLF occurred in 122 patients (7.8%) treated with the BioFreedom stent and in 100 patients (6.3%) treated with the Orsiro stent (RR 1.23, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.94-1.61) (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1. Time-to-event curve for the composite endpoint target lesion failure at two-year follow-up. CI: confidence interval; RR: rate ratio

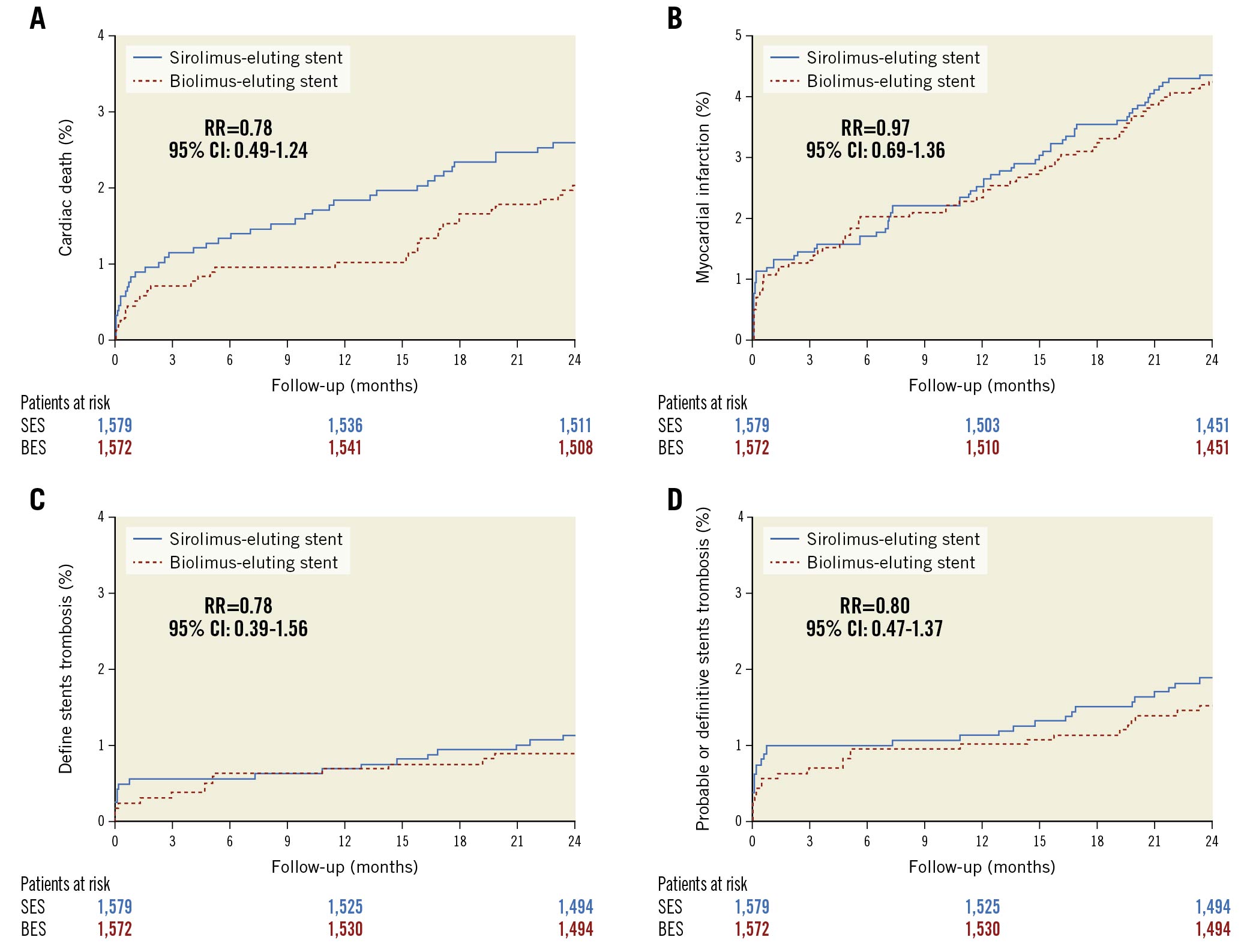

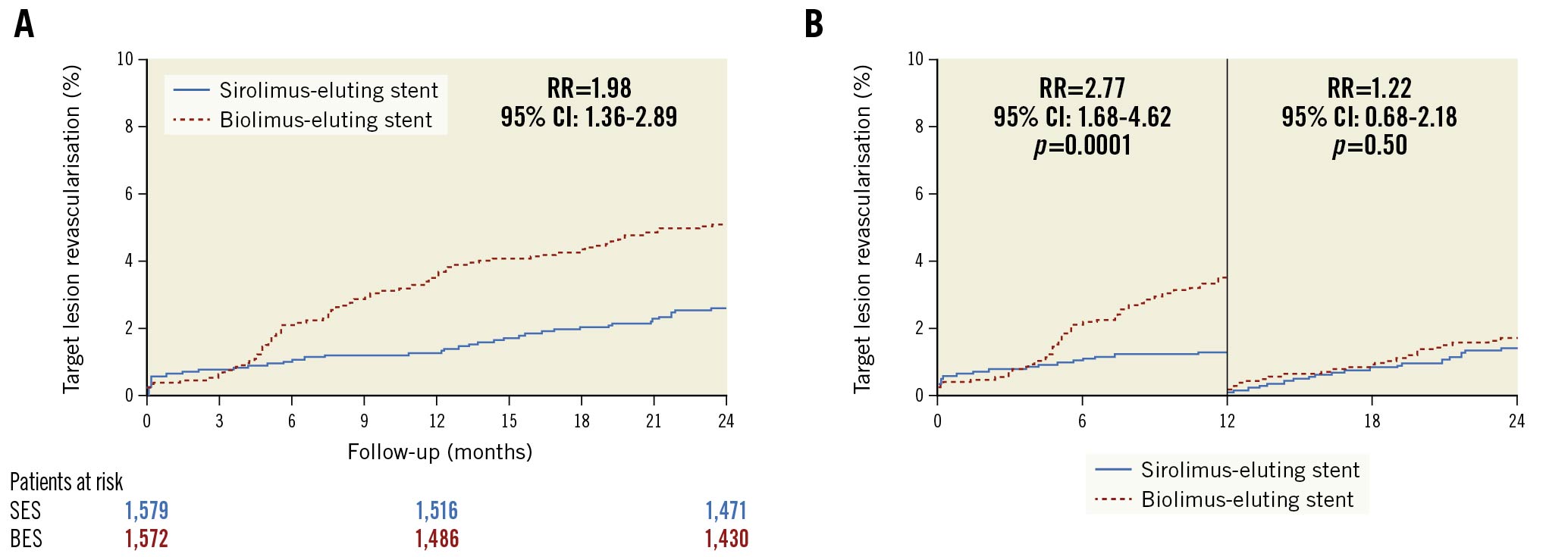

The cumulative incidences of cardiac death, MI, definite stent thrombosis, and probable or definite stent thrombosis were comparable at two-year follow-up (Figure 2A-Figure 2D, Table 2). We have previously demonstrated that the one-year rates of clinically driven TLR were significantly higher in the BioFreedom stent group (3.5% vs 1.3%; RR 2.77, 95% CI: 1.66-4.62, p<0.0001). At two-year follow-up, the difference continued to be significant (Biofreedom stent: n=80 [5.1%] and Orsiro stent: n=41 [2.6%]; RR 1.98, 95% CI: 1.36-2.89, p<0.0004) (Central illustration A). However, the landmark analysis of TLR shows that between one and two years after implantation, the rate of TLR did not differ significantly between the two stents (Biofreedom stent: n=25 [1.7%] and Orsiro stent: n=21 [1.4%], RR 1.22, 95% CI: 0.68-2.18, p=0.5003) (Central illustration B).

Figure 2. Time-to-event curves for the individual components of the primary endpoint at two-year follow-up. A) Cardiac death. B) Myocardial infarction. C) Definite stent thrombosis. D) Definite or probable stent thrombosis. CI: confidence interval; RR: rate ratio

Central illustration. Time-to-event curves for the target lesion revascularisation. A) Target lesion revascularisation at two years of follow-up B) Landmark analysis of the cumulative incidence of target lesion revascularisation up to two years. A landmark was set at one year. CI: confidence interval; RR: rate ratio

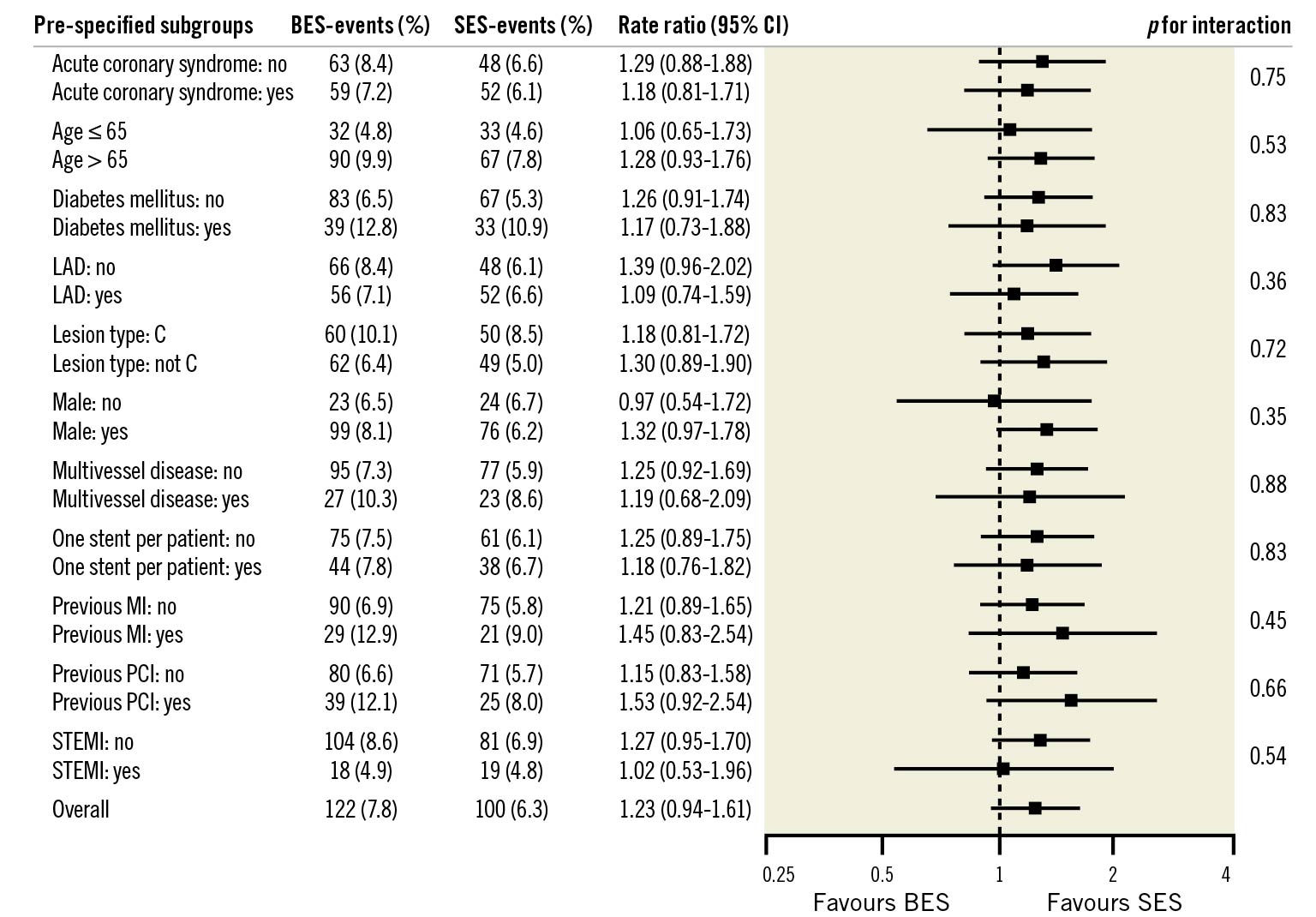

Findings for the primary endpoint, TLF, at two years were consistent across the pre-specified stratified analyses (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pre-specified stratified analysis for the primary endpoint at two-year follow-up. P-values in the Forest plot are all two-sided for interaction. BES: biolimus-eluting stent; CI: confidence interval; LAD: left anterior descending artery; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SES: sirolimus-eluting stent; STEMI: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction

Discussion

The SORT OUT IX trial is the first study to compare the polymer-free biolimus A9-coated BioFreedom stent and the ultrathin strut biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting Orsiro stent. At two-year follow-up, the composite TLF endpoint did not differ significantly between the two stents. Increased risk of TLR continued for two years in the BioFreedom stent group. The higher rate of clinically driven TLR was attributable to the first year after implantation, whereas the risk of TLR was similar between groups in the second year after inclusion.

In the recently published report of the Onyx ONE global randomised trial: “A Randomized Controlled Trial With Resolute Onyx in One Month Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) for High-Bleeding Risk Patients", the BioFreedom stent was compared to a second-generation, polymer-based, zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES) in patients at high bleeding risk and was found to be non-inferior with regard to the safety and efficacy composite outcome10. In accordance with our results, there was a trend for a higher rate of TLR in the BioFreedom stent group (4.0% vs 2.8%)10.

There are important differences in the DES technologies between the two stents used in our trial that may have contributed to the higher TLR rate observed for the BioFreedom stent. First, the study stent has different drug-eluting kinetics. The polymer-free BioFreedom stent releases 90% of its drug within 48 hours9. The Orsiro stent has a silicon carbide coating, a polymer that degrades within 12-24 months and releases its drug within three months. It is known from other studies that DES efficacy is related to the release kinetics of the active drug in the first 30 days, and in particular, the first 10 days17. Our study showed that TLR curves started to separate four months after implantation and were running nearly parallel after one year. At two years, the difference in the TLR rate between the two stents remained significant (5.1% for the BioFreedom stent vs 2.6% for the Orsiro stent). This contrasts with the results from the SORT OUT VII trial18 where the biolimus-eluting Nobori stent (Terumo) was compared to the Orsiro stent. The Nobori stent has the same drug as and similar drug kinetics to the BioFreedom stent (elutes biolimus [15.6 μg/mm2] within 30 days) and showed a similar rate of TLR (4.5% for the Nobori stent vs 3.6% for the Orsiro stent) at two-year follow-up19.

Second, the BioFreedom stent has thicker stent struts (120 µm) than the Orsiro stent (60-80 µm) and strut thickness is known to be relevant for the risk of restenosis20. However, a recently published meta-analysis of ten randomised trials could not show a higher risk of TLR with thicker strut DES21.

Other approaches to enhance the antirestenotic effect of polymer-free DES have been investigated and tested in larger clinical trials. In the "Efficacy Study of Rapamycin- vs. Zotarolimus-Eluting Stents to Reduce Coronary Restenosis (ISAR-TEST-5)" trial, a sirolimus- plus probucol-eluting stent was compared to a ZES in an all-comer population22. The polymer-free, dual-DES stent platform with a thin strut (87 μm) stainless steel stent backbone combined sirolimus with a second drug, probucol, that succeeded in retarding drug release (no traces of rapamycin, probucol, or resin are observable beyond 6–8 weeks)23. The dual-DES platform demonstrated a clinical outcome comparable with a newer-generation durable polymer ZES and the same rate of TLR (10.3% vs 10.4%) at one-year follow-up22. Furthermore, no measurable differences in outcomes were seen at ten-year follow-up24. However, the rate of TLR for the BioFreedom stent in the SORT OUT IX study was much lower at one-year follow-up (3.5%)11 when compared to the dual-DES platform (10.3%)22.

Another attempt to retard drug-eluting kinetics is to use fatty acid chains as a non-polymeric drug carrier. Such a thin strut (80 µm) polymer-free amphilimus-eluting stent (Cre8 EVO; Alvimedica) was recently compared to the latest-generation permanent-polymer ZES in a large randomised trial25. At one-year follow-up, the Cre8 stent was non-inferior to the ZES regarding TLF, and TLR was similar in both groups (2.9% vs 2.6%)25.

Recently, the safety and efficacy of polymer-free DES were compared in a real-world all-comers population treated with either a BioFreedom or a Cre8 stent7. The study population was pooled from two multicentre, observational independent studies at 22 Italian centres—the ASTUTE (Amphilimus Italian multicentre registry)26 and the RUDI-FREE (Polymer free biolimus-eluting stent implantation in all-comers population)27 studies. The main results from the propensity score-matched analysis were that both stents had similar performances as indicated by the comparable risk of TLF at one year (4.0% for the BioFreedom stent and 4.2% for the Cre8 stent). Safety and efficacy profiles were favourable and comparable in both groups. No difference in the rates of TLR (1.5% vs 2.2%) and definite/probable stent thrombosis (0.9% vs 0.8%) was found in a real-world setting7.

The new BioFreedom Ultra drug-coated stent with a thin-strut (84-88 µm) cobalt-chromium platform with similar drug dose and release kinetics as the BioFreedom stent has recently received CE certification. The efficacy of the new BioFreedom Ultra stent was evaluated in a randomised comparison to the BioFreedom stent in an all-comers population undergoing PCI28. At nine-month follow-up, the BioFreedom Ultra stent was non-inferior to the BioFreedom stent with regard to the primary endpoint (late lumen loss) and TLR did not differ between these two stents28. Larger studies powered for clinical endpoints are warranted to compare the efficacy of this new platform with newer-generation DES.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the study was designed to detect non-inferiority for TLF at one-year follow-up. Secondly, the polymer degradation of the Orsiro stent takes place after 12-24 months. The benefit of biodegradable polymer DES might therefore be expected to take effect beyond the degradation time of the polymer and thus even longer follow-up is necessary. Consequently, the safety and performance of the stents included in SORT OUT IX will be assessed up to five years after implantation.

Conclusions

In summary, at two-year follow-up the composite endpoint TLF did not differ between the two stents. Increased risk of TLR continued for two years in the BioFreedom stent group. However, the high rate of clinically driven TLR mostly occurred in the first year after implantation.

Impact on daily practice

SORT OUT IX is the first study to compare the BioFreedom stent to a modern DES in a population-based all-comers setting. Two-year TLF did not differ for the BioFreedom stent and the Orsiro stent. The risk for TLR, however, was significantly higher in the BioFreedom stent treated patients compared to the Orsiro stent treated patients. The results of this randomised trial support the use of the BioFreedom stent among patients with high-risk for bleeding when used with a one-month course of dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Acknowledgements

The SORT OUT IX steering committee formulated the study design, and all authors subsequently accepted this. L.O. Jensen and J. Kahlert were responsible for data management and for design and implementation of the statistical analysis. All other authors took part in patient enrolment and data collection. L.O. Jensen and E.H. Christiansen contributed to the design of the statistical analysis and the interpretation of results. J. Ellert-Gregersen and L.O. Jensen drafted the manuscript, which was subsequently seen and reviewed by all authors. All authors have seen the final submitted manuscript, and they agree with its contents. J. Ellert-Gregersen had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication in EuroIntervention.

Funding

This study was an investigator-initiated study from the SORT OUT organisation. It was supported by equal, unrestricted grants from Biosensors and Biotronik. The two companies did not have access to the study database and were not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, or interpretation of results. Also, the companies did not have the opportunity to review the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility to submit for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

L.O. Jensen has received research grants from Biotronik, Biosensors and Orbush Neich for her institute. M. Maeng has received lecture and advisory board fees from Novo Nordisk. T. Engstrom has received speakers’ fees from Abbott. E.H. Christiansen has received grants from Biosensors and Biotronik for his institute. P.M. Freeman received honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences and Meril Lifesciences, and an educational grant from AstraZeneca. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.