The number of patients treated with chronic oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy globally is large and is projected to expand further in the future as the population ages and medical conditions requiring anticoagulation become increasingly prevalent. Up to one fourth of these typically multi-morbid patients also have coronary atherosclerotic disease and may thus become candidates for a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) during their lifetime. Conversely, an estimated 5-10% of all patients undergoing PCI – currently the most frequent medical intervention – receive OAC1. While long-term antithrombotic management of patients who are eligible for OAC and undergo PCI represents a major challenge, their optimal periprocedural management also remains controversial. On the one hand, performing the intervention without OAC interruption offers continuous anti-ischaemic protection yet it presumably raises the peri-interventional bleeding risk due to the combined effect of OAC, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), and possibly additional administration of heparin or other antithrombotic medications (e.g., glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors). On the other hand, temporary OAC interruption treatment intuitively mitigates the excessive haemorrhagic risk; transient administration of short-acting parenteral agents such as unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin during the interruption of OAC, referred to as bridging therapy, is a widely, mostly empirically applied approach that is nonetheless not supported by adequate evidence and has in fact been associated with increased bleeding risk during PCIs or other surgical or medical interventions1. The need to balance the risk of thromboembolism (in case of OAC interruption) vs. the risk of haemorrhagic complications (in case of continuous anticoagulation) has been an ongoing matter of debate, and optimal management remains to be definitively defined.

Against this background, Dewilde et al add novel, important insights into this clinically relevant issue in a recent article in EuroIntervention2. This is a post hoc analysis of the WOEST study, a randomised trial that compared clopidogrel alone vs. the combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin in 573 patients who were treated with long-term OAC and underwent PCI. The present analysis assessed 30-day and one-year outcomes according to a periprocedural practice of uninterrupted anticoagulation (UAC) (n=241) vs. temporarily interrupted OAC (n=322). The authors report no difference of any bleeding events between these two treatment groups within 30 days (19.1% vs. 17.4%, respectively; p=0.51) and throughout one year of follow-up (35.6% vs. 29.8%; p=0.12), although minor (BARC 1 and TIMI minimal) bleeding tended to be more common among patients with continuous OAC. The risk of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and of ischaemic outcomes overall did not differ between the two groups. These results held true in the subgroup of patients with atrial fibrillation (n=326). Collectively, these findings support the use of UAC during elective PCI for either stable coronary artery disease or an acute coronary syndrome, since this approach does not appear to result in excessive bleeding and at the same time it avoids more complex and costly schemata involving OAC withdrawal, transient substitution and re-initiation. Indeed, many would argue that the somewhat higher frequency of minor bleeding events with a strategy of UAC is a price worth paying for an otherwise simple strategy with non-differing ischaemic and net clinical outcomes compared with the alternative approach of OAC cessation and bridging.

While the message of the present WOEST analysis is clear and the potential implications for everyday practice are relevant, certain considerations need to be taken into account. First, although reporting clinical outcomes up to one year clearly adds power by including a greater number of analysable events, it is pathobiologically questionable whether, and through which mechanisms, periprocedural antithrombotic management may exert such a prolonged effect on bleeding and/or ischaemic adverse events. Therefore, it would probably be more reasonable to focus mainly on the 30-day outcomes, and also on clinically more relevant (i.e., more severe) bleeding events. While a numerically twofold higher rate of BARC 3 bleeding and a fivefold higher rate of TIMI major bleeding within 30 days in the bridging therapy group is a notable signal, restricting the analysis to 30 days and to severe haemorrhagic complications substantially limits the power and clearly hampers the determination of differences in bleeding risk with a high level of certainty in this observational study. Second, the group of patients in whom OAC was interrupted is referred to as a “bridging group”; however, the authors state that the periprocedural management in this group was determined by the operators at each study centre, although the proportion of patients who did or did not receive actual bridging with heparin during the days of OAC interruption other than during the procedure itself is not presented2. Considering that at least a proportion (albeit not specified) of patients in the “bridging group” probably did not receive heparin bridging before or following the intervention, the finding of non-differing bleeding rates between the two study groups is reassuring (i.e., patients who continued OAC did not have an excess of bleeding despite the fact that the comparator group included some patients who stopped warfarin for several days and did not receive heparin other than during the intervention per se).

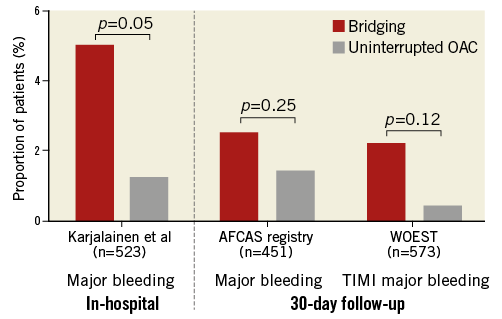

Notwithstanding these considerations, the report by Dewilde et al2 is an important contribution in the field by representing the largest cohort to date addressing the issue of optimal OAC management during PCI. Previous relevant investigations include descriptive reports demonstrating the feasibility of diagnostic coronary angiography and PCI in the setting of continuous OAC3-5, and there are very few non-randomised studies that compared outcomes between the two alternative strategies, i.e., UAC vs. OAC interruption with bridging6,7. Those earlier, smaller investigations reported essentially similar findings to the WOEST analysis (Figure 1), although direct comparisons are hindered by the heterogeneity of reported endpoints and follow-up durations. Together, these findings support the 2010 expert consensus paper from the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology, which recommended uninterrupted OAC in moderate- to high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (AF)1. In the absence of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to address this issue, these observational data are currently the best available sources of evidence to provide guidance and inform our everyday practice.

Figure 1. Major bleeding events in patients with or without OAC interruption during PCI. Incidence of in-hospital major bleeding in the study by Karjalainen et al7 (left), 30-day major bleeding in the AFCAS registry6 (middle), and 30-day TIMI major bleeding in WOEST2 (right), in patients with interruption of oral anticoagulation (OAC) and temporary bridging (red bars) vs. uninterrupted OAC (grey bars) during percutaneous coronary interventions.

Procedural aspects other than peri-interventional antithrombotic management greatly affect the risk of bleeding complications during PCI. In the WOEST analysis, radial access was more common among patients with maintenance of therapeutic warfarin (31% vs. 22% in bridged patients)2. Although the specific location of bleeding is not reported2, one can speculate that the relative preponderance of transradial interventions among the UAC patients (a rather expected observation considering that the access route was determined by the operator in a non-randomised fashion) is likely to have resulted in fewer access site-related bleeding complications in the UAC treatment group. Vascular access-site bleeding events represent the most frequent bleeding complications during the peri-interventional period in patients undergoing PCI8 and are substantially reduced when the radial route is used9. Not surprisingly, some evidence indicates that the clinical value of the radial approach for reduction of access-site bleeding is particularly noticeable among orally anticoagulated patients10,11.

The results of the WOEST analysis and of earlier studies in the setting of PCI2-7 are overall in line with evidence regarding overall periprocedural management of orally anticoagulated patients. A meta-analysis of 34 studies assessing heparin bridging in patients on vitamin K antagonists demonstrated an increased risk of overall and major bleeding, and a similar risk of thromboembolic events in patients with periprocedural bridging vs. UAC in the setting of elective invasive procedures or surgery12. The large-scale “Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation” (ORBIT-AF) study recorded interventions requiring OAC interruption in 2,200 (30%) out of 7,372 patients with atrial fibrillation throughout a median follow-up of two years13. Heparin bridging in patients with OAC interruptions prior to surgery or non-surgical interventions was associated with a fourfold higher risk of bleeding and a twofold higher risk of major complications13. Only one tenth of patients (n=244) underwent cardiac catheterisation in that analysis, and no sensitivity analysis focusing on PCI patients was reported13. In patients undergoing cardiac device implantation or catheter ablation, continuing OAC is associated with better outcomes and less frequent bleeding complications compared with OAC interruption and heparin bridging14. Overall, it is noticeable that – according to the available, non-randomised evidence – heparin bridging appears to be associated with similar bleeding hazards to UAC in the setting of PCI2-7 but with higher bleeding in non-PCI, surgical or medical interventions12-14. This was largely confirmed in the recently published BRIDGE study in which 1,884 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing elective surgery or other invasive procedures were randomised to bridging with low-molecular weight heparin vs. placebo after perioperative warfarin interruption15. OAC interruption without heparin bridging was non-inferior in terms of arterial thromboembolism and resulted in fewer major bleeding events15. Upcoming randomised trials, including PERIOP-2 (NCT00432796) and BRUISECONTROL2 (NCT01675076) are expected to shed more light on the clinical benefits of UAC vs. OAC interruption with or without bridging during surgery, invasive procedures and device-related interventions. Randomised trials in the particular setting of PCI are not expected in the near future.

If in the setting of PCI a strategy of UAC compared with OAC interruption (with or without heparin bridging) appears to be non-inferior, but not necessarily superior with regard to clinical outcomes, the question then arises: what is the rationale for opting for one approach over the other in everyday practice? The answer probably lies in the presumed advantages of UAC vs. bridging that are not reflected in hard endpoints of existing studies: UAC is a simpler periprocedural management in terms of logistical requirements, and presumably allows for shorter duration of hospital stay with all the associated socio-economic benefits. Re-initiation of conventional OAC after a temporary withdrawal would probably require a prolonged hospital stay or at least subsequent repetitive ambulatory controls with the shortcoming of possible fluctuations of INR values in case of warfarin interruption and re-initiation. These practical advantages are difficult to capture in scientific analyses but remain important in daily clinical practice, at least as far as OAC with warfarin is concerned. Careful assessment of the risk for thromboembolism and bleeding hazard in the individual patient is also critical for the infrequently studied question of the optimal periprocedural management of patients receiving OAC16. Until more robust, RCT-derived evidence is available (including patients who receive non-vitamin K antagonists), a strategy of uninterrupted OAC during PCI appears both feasible and safe. It fulfils the timely Hippocratic requirement of primarily not harming (primum non nocere), and it should be preferred for practical reasons.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.