Abstract

Aims: The management of patients on long-term oral anticoagulation and referred for percutaneous coronary interventions represents a substantial challenge to the physician who must balance the risks of periprocedural haemorrhage, thrombotic complications and thromboembolism.

Methods and results: Currently, a standard recommendation for these patients has been the discontinuation of warfarin before invasive cardiac procedures, since uninterrupted anticoagulation is assumed to increase bleeding and access site complications. Unfractionated or low molecular weight heparins are administered as a “bridging therapy” in patients at moderate to high risk of thromboembolism. The present review summarises the available data on the safety of performing coronary interventions during uninterrupted oral anticoagulation therapy and shows that bridging therapy offers no advantage over this simple strategy and prolongs hospitalisation and may delay interventions in acute coronary syndromes. Sub-therapeutic anticoagulation during crossover phases may also increase the potential for thromboembolism.

Conclusions: Bridging therapy offers no advantage over the simple strategy of performing cardiac interventions during uninterrupted therapeutic oral anticoagulation therapy.

Introduction

It is estimated that 5% of patients undergoing coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are on long-term oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy because of underlying chronic medical conditions such as atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism, heart failure or mechanical heart valve1. Management of such anticoagulated patients and undergoing PCI remains challenging, both during the procedure and in the longer term given the concurrent indications for anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents post-PCI and stenting.

There are two main options in approaching the issue of periprocedural anticoagulation. The most common recommendation is that OAC should be discontinued a few days prior to coronary interventions and the periprocedural INR level should be <1.52. If the patient is considered to be at increased risk of thromboembolism, either unfractionated (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) are administered as a bridging therapy during the invasive procedure until INR has been restored to the therapeutic levels2-4. Another emerging option is to continue the therapeutic OAC throughout the periprocedural period with no interruptions or heparin bridging.

Given the lack of randomised trials, the use of any antithrombotic strategies during coronary interventions in this patient group is based on consensus1,3. The present review is a critical appraisal of the recommendations for “bridging therapy” which are commonly used in peri-PCI patients who are taking OAC. The latter group of patients is often heterogeneous, including those taking OAC for venous thromboembolism and prosthetic valves, as well as for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation.

Periprocedural anticoagulation

The safety and feasibility of heparin bridging therapy has been evaluated in patients who receive long-term OAC and require interruption of OAC for elective surgery or an invasive procedure5-9. For example, Spyropoulos et al showed a major bleeding rate of 3.3% with UFH and 5.5% with LMWH in a registry study of 901 patients with bridging therapy for an elective surgical or invasive procedure6. Another prospective single-arm study reported a 6.7% incidence of major bleeding with LMWH bridging therapy in patients at risk of arterial embolism undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery or an invasive procedure7, but lower (2.9%) rates of major bleeding have been reported5. Reports focusing on PCI per se are limited, but in the retrospective analysis by MacDonald et al, 4.2% of 119 patients developed enoxaparin-associated access site complications during LMWH bridging therapy after cardiac catheterisation10.

Recently, the safety and efficacy of bridging therapy has been questioned in patients undergoing pacemaker implantations or pulmonary vein ablation11-16. Bridging therapy offered no advantages in any of these studies and might even increase bleeding events11. The practical management guide concludes that a strategy involving postoperative bridging with intravenous heparin confers a high risk of bleeding, whereas perioperative continuation of OAC appears to confer a lower risk of bleeding during pacemaker implantation15. Heparin bridging prolongs hospitalisation and may increase the risk of thromboembolism associated with sub-therapeutic anticoagulation17,18. Bridging therapy may also contribute to the fact that patients with acute coronary syndromes and chronic OAC are significantly less likely to undergo coronary angiography and PCI, and their waiting times for these procedures are longer than in patients not on OAC17.

A simple strategy of temporary replacement of warfarin by dual antiplatelet therapy is a tempting alternative, but does not seem to be a good long-term option in the light of the ACTIVE-W study and other recent observational studies on coronary stenting19-21. Another potential strategy is a temporary adjustment of warfarin dosing to reach a perioperative INR of 1.5 to 2.0. Such moderate-dose OAC therapy with warfarin has been shown to be safe and effective in the prevention of thromboembolism after orthopaedic surgery in a single-centre prospective registry22. The low level of anticoagulation may be adequate for coronary angiography, but is probably not sufficient for PCI, since PCI requires procedural anticoagulation not only to avoid thromboembolic complications, but also thrombotic complications of the intervention, and only highly selected low-risk procedures may be safe without anticoagulation23.

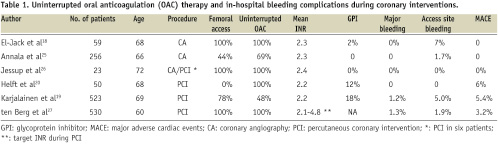

Periprocedural anticoagulation has traditionally been performed with UFH or more recently with LMWHs or direct thrombin inhibitors. Theoretically, therapeutic uninterrupted OAC may also facilitate PCI, since warfarin is known to increase activated coagulation time in a predictable fashion24. Supporting this view, recent findings suggest that uninterrupted anticoagulation with warfarin could replace heparin bridging in catheter interventions with a favourable balance between bleeding and thrombotic complications (Table 1)11,18-20,25-27.

In these non-randomised studies, this simple strategy was at least as safe as that of more complicated bridging therapy. The incidence of bleeding or thrombotic complications was not related to periprocedural INR levels and propensity score analyses suggested that the bridging therapy may actually lead to an increased risk of access site complications after PCI19. Similarly, high therapeutic (INR 2.1-4.8) periprocedural OAC led to the lowest event rate with no increase in bleeding events in 530 patients undergoing balloon angioplasty in an early PCI study27. Another early report suggested that stenting could be performed safely under full OAC with no subacute thrombosis or femoral bleeding complications in spite of 8 Fr femoral sheaths being used28. In line with these PCI studies, no major bleeding events were observed in 30 patients randomised to therapeutic periprocedural warfarin anticoagulation in a small study on diagnostic coronary angiography, although all procedures were performed using transfemoral access. Of importance, it took a median of nine days for INR to return to therapeutic levels in the patient group assigned to discontinue warfarin for > 2 days18.

Performing PCI without interruption of warfarin

Performing coronary angiography and PCI without interrupting warfarin has several theoretical advantages. Wide fluctuations in INR are known to be common and long lasting after interruption necessitating prolonged bridging therapy29. Secondly, warfarin re-initiation may cause a transient prothrombotic state due to protein C and S suppression29-31. The fear for “unopposed” fatal bleedings seems also to be overemphasised, since the anticoagulant effect of warfarin can be rapidly overcome by a combination of activated blood clotting factors II, VII, IX and X or by fresh frozen plasma.

It is also noteworthy that LMWHs are not innocent in this respect, since protamine sulphate can only partially neutralise their anticoagulant effect. Fondaparinux, a recommended drug for acute coronary syndromes, may be even more problematic in this respect, since it is not neutralised by protamine sulphate and there are no specific antidotes for the drug. It may also be noteworthy that prolonged UFH and LMWW treatment increases the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

In addition to the effective anticoagulation, potent antiplatelet treatments are needed during the periprocedural period to prevent stent thrombosis. Current guidelines recommend that both aspirin and clopidogrel should be used peri-PCI and to be continued for at least one month after elective stenting with bare metal stents and up to 12 months after drug eluting stents or in acute coronary syndromes4. The recommendation is based on the early randomised trials evaluating the combination of aspirin and warfarin in the prevention of stent thrombosis32,33 and showing that the rate of stent thrombosis was unacceptable high without dual antiplatelet therapy. At present, triple therapy (warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel) is the most often recommended option to prevent stent thrombosis in this patient group, but the increase of bleeding risk is the downside of the combination. No prospective randomised studies have yet addressed this issue and in the 2006 ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines for Atrial Fibrillation, for example, there is a Class IIb recommendation that after PCI low-dose aspirin (less than 100 g/day) and/or clopidogrel (75 g/day) concurrent with anticoagulation should be used in patients with atrial fibrillation. Data on the safety of warfarin plus clopidogrel in combination are more limited, but this strategy is currently under active investigation1,34,35. At present, this combination may be an alternative in patients with high bleeding risk and/or absent risk factors for stent thrombosis. Of interest, a recent study showed that a coumarin derivative phenprocoumon significantly attenuated the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel36. Bare metal stents should be preferred over drug eluting stents and even plain old balloon angioplasty may be an option if an acceptable result can be achieved without stenting to minimise the length of triple therapy. According to a pooled analysis the duration of triple therapy is critical for the bleeding events, since the incidence of major bleeding increased from 4.6% to 10.3% when the treatment period increased from one month to 6-12 months or more1. The importance of avoiding bleeding complications has become more and more evident, since they have turned out to be highly predictive of mortality across a broad spectrum of patients undergoing PCI37.

Randomised trials have shown a modest increase (2.4% vs. 1.4%) in bleeding risk associated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) use during acute coronary syndromes38. There are no safety data from clinical trials on warfarin treated patients, since this patient group has been excluded from all randomised GPI studies. In real world practice, warfarin treated patients are less often treated with GPIs17,39,40. Not surprisingly, bleeding complications seem to represent a significant limitation to the effectiveness of GPIs and the GPI use has been associated with a 3-13-fold risk of early major bleeding in warfarin treated patients19,25,41,42. GPIs seem to increase major bleeding events irrespective of periprocedural INR levels and should be used with caution in this patient group. At present, there are no data on safety and efficacy of bivalirudin in combination with OAC.

In addition to the choice of antithrombotic strategy, vascular access site selection may also have an impact on in-hospital bleeding complications. Radial artery access has been associated with a reduced risk of access site bleeding and other vascular complications in meta-analysis of randomised trials and registry studies43,44. In line with these reports, the femoral access route was an independent predictor (hazard ratio 9.9; 95% CIs 1.3-75.2) of access site complications in the 523 warfarin treated patients19. On the basis of current information, a radial approach should be always considered since haemostasis is rarely an issue with this access site.

What do the guidelines say?

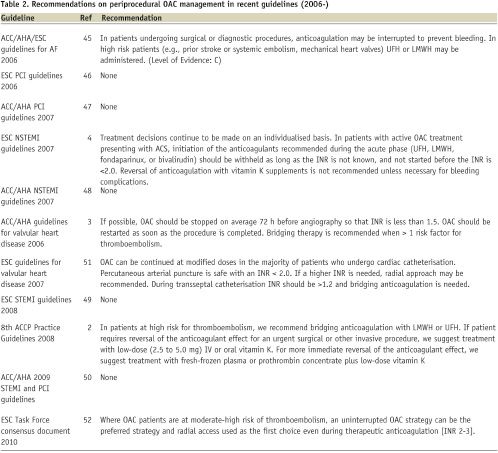

Recent guidelines include only limited comments on long-term OAC during peri-PCI period and many have even ignored this complicated issue2-4,45-52 (Table 2).

The American College of Chest Physicians practice guidelines make a general recommendation to use bridging therapy for major surgery in patients at high risk of thromboembolism, but do not specifically address PCI patients3. The European guidelines for valvular heart disease comment that OAC can be continued at modified doses in the majority of patients who undergo cardiac catheterisation51. Arterial puncture is deemed safe when INR remains below 2.0. If a higher INR is needed, a radial approach may be recommended. The AHA/ACC guidelines for valvular heart disease recommend that the periprocedural INR level should be <1.52. The recently published ESC Task Force consensus document52 is the only one to state that an uninterrupted OAC strategy can be preferred in patients with atrial fibrillation who are at moderate-high risk of thromboembolism, and that the radial access is recommended as the first choice during therapeutic anticoagulation [INR 2-3].

Conclusion

In the light of the limited research data, the simple strategy of uninterrupted OAC is a tempting alternative to bridging therapy and may be most useful for the patients with high risk of thrombotic and thromboembolic complications. Triple therapy is recommended for the prevention of stent thrombosis, but its duration should be individualised according to the stent type and bleeding risk of the patient. GPIs increase bleeding risks and should be used with caution. A radial approach for PCI is the preferable access route.

However, these recommendations are largely based on limited evidence obtained from small, single-centre and retrospectively analysed cohorts. Thus, there is a definite need for large scale registries and prospective clinical studies to determine the optimal antithrombotic management of patients with atrial fibrillation at intermediate or high thromboembolic risk undergoing coronary interventions. Prospective, multi-centre European registries (AFCAS and LASER) will hopefully shed light on this common issue. Ongoing randomised trials (ISAR-TRIPLE and WOEST) will give more information on the safety of various antiplatelet regimens adopted after PCI in this patient population.