CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 68-year-old man was referred for stable angina pectoris and a large apical perfusion defect on stress myocardial scintigraphy. Medical history included chronic oral anticoagulation with warfarin due to long-standing atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia.

INVESTIGATION: Coronary angiography.

DIAGNOSIS: Severe stenosis of the mid left anterior descending coronary artery.

TREATMENT: Percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of drug-eluting stent.

KEYWORDS: anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs, atrial fibrillation, bleeding, drug-eluting stent

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

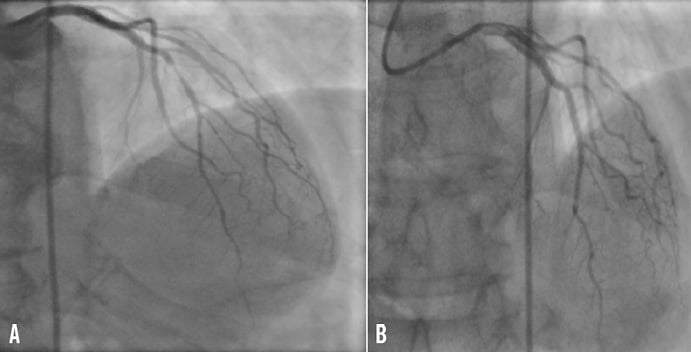

A 68-year-old man was referred to our hospital in March 2009 for stable angina pectoris and a large apical perfusion defect on stress myocardial scintigraphy. His medical history was significant for chronic oral anticoagulation with warfarin due to long-standing atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia. Coronary angiography revealed severe stenosis of the mid left anterior descending coronary artery (Figure 1A). On the basis of the clinical and angiographic findings, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was planned. Despite the need for continuous warfarin therapy in this patient, the decision to implant a drug-eluting stent was made due to the small size of the coronary vessel and the history of diabetes. Therefore, warfarin was discontinued three days prior to the procedure and replaced with unfractioned heparin i.v. Six hours before PCI, a clopidogrel loading dose (300 mg) was administered. Under local anaesthesia, a 6 Fr sheath was introduced in the right common femoral artery. A supplement of unfractioned heparin was administered i.v. to achieve an activated clotting time >250 sec. Stenosis predilatation was performed with a 2.0×15 mm Sprinter Legend balloon catheter (Medtronic, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a 2.75×15 mm XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, IL, USA) was implanted with good angiographic result (Figure 1B). The arterial sheath was removed at the end of the procedure and haemostasis was obtained with AngioSeal 6 Fr (St. Jude Medical, Minnetonka, MN, USA). On day one post intervention, warfarin therapy was reintroduced. The patient had an uneventful postprocedural course and was discharged 48 hours after PCI on a triple antithrombotic therapy consisting of aspirin 75 mg/day, clopidogrel 75 mg/day, and warfarin monitored to maintain an international normalised ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 2.5. A proton pump inhibitor (omeprazol 20 mg/day) was prescribed for gastric protection. At discharge, haemoglobin was 13.6 g/dl.

Figure 1. Selective angiogram of the left coronary artery showing severe stenosis of the mid left anterior descending coronary artery before (A) and after treatment with drug-eluting stent (XIENCE V) implantation (B).

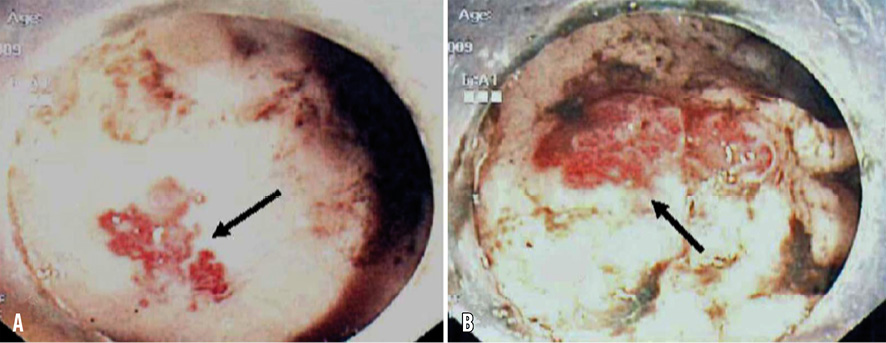

The patient remained asymptomatic for 12 days and then suddenly developed several episodes of melaena in quick succession followed by marked hypotension. Twenty-four hours later, he was brought to our emergency room in haemorrhagic shock with a blood pressure of 80/60 mmHg, a haemoglobin value of 5.8 g/dl and an INR of 4. After immediate administration of plasma expanders to achieve haemodynamic stability, the patient received a transfusion of 4 units of red blood cells. All antithrombotic therapy was withdrawn for 24 hours. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, performed several hours after admission, excluded the presence of a gastroduodenal ulcer and colonoscopy detected multiple angiodysplastic lesions in the caecum that were the source of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (Figure 2). At this point, we were faced with a serious management dilemma in an atrial fibrillation patient with strong indication for antiplatelet therapy post PCI and drug-eluting stent implantation. The first issue was the most appropriate gastroenterology treatment to achieve colonic haemostasis. The second dilemma was the choice of safe and effective antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications for use after achieving definitive haemostasis in order to prevent stent thrombosis, cardiogenic embolisation and, at the same time, to avoid re-bleeding.

Figure 2. Colonoscopy showing two adjacent regions (A and B) of caecal angiodysplasia (arrows).

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

This patient presented with melaena and severe anaemia following the implantation of an everolimus-eluting stent and triple antithrombotic therapy. Bleeding was caused by multiple angiodysplasias in the caecum. Gastrointestinal angiodysplasias are single or multiple non-variceal vascular anomalies of the digestive tract not associated with angiomatous lesions of the skin or other organs. These angiodysplasias consist of dilated mucosal capillaries communicating with dilated and tortuous submucosal veins1. They are mainly located in the right colon and caecum (80%), but may also be found in the small intestine (15%) and stomach. Angiodysplasias account for 3-5% of occult or overt lower gastrointestinal bleeds; although spontaneous bleeding cessation occurs in about 90% of cases, the risk of re-bleeding is high, (26% and 45% for overt re-bleeding; 46% and 64% for occult re-bleeding at one and three years, respectively)2,3. Over the years, a variety of medical and endoscopic interventions has been proposed to treat bleeding colonic angiodysplasias and prevent re-bleeding, but the available evidence for each of these treatments is scarce and generally of low quality1. The endoscopic treatments proposed include thermal ablation by argon plasma coagulation, electrocoagulation, laser photocoagulation, cryotherapy, elastic band ligation, mini loops and endoclips. Medical treatments include oestrogens and progesterone, octreotide and thalidomide. Concerning endoscopic treatments, no randomised controlled trials comparing different techniques exist. The largest open prospective series of argon plasma coagulation4,5 shows that this technique is effective and safe (re-bleeding rate 7-15%, complications rate 1.7-7%). In one of these studies4, 31/40 patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy did not taper their medications during follow-up. Monopolar and bipolar electrocoagulation have also been used, with somewhat less favourable results (recurrence rate ranging between 18.5 and 53%)1.The evidence on the use of the other endoscopic methods is even more limited. Concerning medical treatments, oestrogens and progesterone have been found to be ineffective in controlled trials1; subcutaneous octreotide in a non-randomised controlled trial6, and intramuscular long-acting octreotide in a small case series7 were effective in preventing re-bleeding in 77% and 72% of cases, respectively. Recently, thalidomide has also been proposed because of its antiangiogenic effect. A total of 17 cases have been reported in case reports and small case series1, with encouraging results.

In this patient, the goals of treatment should be to achieve haemostasis and to prevent re-bleeding, since the patient will have to maintain some form of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy to prevent stent thrombosis. I would treat the bleeding angiodysplasias with argon plasma coagulation, which is both effective in achieving haemostasis and safe. Since angiodysplasias are often multiple and can involve both the colon and the small bowel in the same patient, after haemostasis is achieved I would perform capsule enteroscopy to exclude other potential sources of bleeding8. If small bowel angiodysplasias are also present, I would treat them with double-balloon enteroscopy and argon plasma coagulation. To prevent re-bleeding, I would also consider monthly intramuscular injections of long-acting octreotide.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

Abbreviations

AFib: atrial fibrillation

DES : drug-eluting stent

INR: international normalised ratio

LAA: left atrial appendage

LAD: left anterior descending artery

The post-coronary stenting management of patients who have atrial fibrillation (AFib) superimposed on coronary artery disease is one of the more difficult issues confronting the interventional cardiologist. This is a common problem encountered in nearly 7% of patients we treat9. The case presented by Fabbiocchi and colleagues shrewdly illustrates the difficulty in trying to achieve both platelet inhibition to prevent thrombosis and coagulation cascade interruption to prevent thromboembolism without inducing serious bleeding.

The case can be summarised as severe/life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding in a 68-year-old diabetic hypertensive male, 12 days after treatment of a discrete mid-LAD lesion with a single 15 mm everolimus-eluting stent.

As we develop a management plan, it would be helpful to parse out the key issues:

WHAT IS THE STROKE RISK AND HOW IS IT IMPACTED BY DUAL ANTIPLATELET THERAPY COMPARED TO WARFARIN?

There have been many instruments developed to estimate the risk of stroke for patients with atrial fibrillation. The CHADS2-VASc is among the most sophisticated. This patient has a CHADS2-VASc score of 4 (hypertension [1], diabetes [1], vascular [coronary] disease [1] and 65-74 years of age [1]) which translates to an annual stroke risk of 4%10. A large meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies estimates a 60% reduction with dose-adjusted warfarin and a 20% reduction with aspirin alone when compared to no treatment11.

The relative lack of efficacy of aspirin plus clopidogrel in preventing stroke in AFib patients when compared to warfarin alone was demonstrated in the ACTIVE W study. This study was stopped early due to demonstration of the superiority of warfarin in reducing the incidence of stroke, non-CNS embolic event, MI or vascular death: the primary endpoint occurred in 5.6% of patients in the aspirin plus clopidogrel arm vs. 3.9% in the oral anticoagulation arm (relative risk 1.44 [1.18-1.76]; p=0.0003)12.

Recently, a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran) and Factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban and apixaban) have been compared to warfarin in the prevention of stroke in AFib patients. As a group, these drugs provide coagulation cascade inhibition in a more consistent fashion without the variability and the constant monitoring required for warfarin13-15. A more in-depth review is beyond the scope of this commentary.

In summary, the patient under consideration is at high risk for stroke, and long-term coagulation cascade interruption with warfarin, a direct thrombin inhibitor or Factor Xa inhibitor is clearly indicated.

WHAT IS THE STENT THROMBOSIS RISK AND HOW IS IT IMPACTED BY DUAL ANTIPLATELET THERAPY COMPARED TO WARFARIN?

The superiority of aspirin plus P2Y12 inhibitor over aspirin alone and aspirin plus warfarin in decreasing the rate of stent thrombosis at 30 days was established in the STARS trial: aspirin plus ticlopidine (0.5%), aspirin alone (3.6%) and aspirin plus warfarin (2.7%) (p=0.001). Bleeding rates were similar with aspirin plus warfarin (6.2%) and aspirin plus ticlopidine (5.5%), and were significantly higher than with aspirin alone (1.6%) (p<0.01)16.

Risk factors for thrombosis could be categorised as systemic (diabetes), anatomic (lesion location and complexity), and behavioural (compliance). In our patient, diabetes provides a justification for DES selection but places him at increased risk of ST. Lesion location in the LAD has been identified as a risk factor for ST in many studies17. Despite these two risk factors, the clinical setting of the current case (stable angina) and the discrete nature of the lesion treated with a single third-generation stent with a good angiographic result places this patient at the lower end of the risk spectrum for ST.

WHAT IS THE BLEEDING RISK AND HOW IS IT IMPACTED BY DUAL ANTIPLATELET THERAPY COMPARED TO WARFARIN?

Precise estimation of this patient’s bleeding risk going forward is difficult, though it is not difficult to intuit that there are many factors which place him at high risk for re-bleeding.

A recently published study using Danish administrative data characterises the relative risks of bleeding with aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin alone and in combination. This study linked discharge data from 118,000 patients with AFib with prescriptions filled for aspirin, warfarin and/or clopidogrel. The patients were monitored for rehospitalisation and death. It was observed that bleeding rates were increased by a factor of 1.8 with the addition of aspirin, 3.08 with the addition of clopidogrel, and 3.7 with the addition of aspirin and clopidogrel18.

The accompanying review provided by Dr De Franchis outlines the issues associated with angiodysplasia.

An important part of the history is the increased INR noted on readmission as well as an understanding that the patient had previously tolerated warfarin therapy without incident. It is reasonable to conjecture that the addition of aspirin and clopidogrel to warfarin (triple therapy) with an INR of 4 precipitated the gastrointestinal haemorrhage in this patient.

The above discussion outlining the difficulties in combining coagulation cascade inhibition with antiplatelet therapy provides the rationale for left atrial appendage (LAA) closure. The most rigorously studied LAA closure device is the Watchman device (Atritech/Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) which was evaluated in the Protect AF trial. In this 707-patient trial, LAA closure was compared to warfarin in AFib patients at moderate to high risk for stroke19. A significant reduction in the primary efficacy endpoint (stroke, cardiovascular death and systemic embolism) was observed in the Watchman group (3.0 per 100 patient years) compared to the warfarin group (4.9 per 100) (RR 0.62 [0.35-1.25]). These results were tempered by an increase in safety events (primarily procedurally associated pericardial effusions). This study validated LAA closure as an important therapeutic option for these patients. Procedural concerns are being addressed with improved patient selection and technique as well as the introduction of an updated Watchman design, and next-generation devices, e.g., Amplatz Cardiac Plug (AGA/St. Jude Medical), WaveCrest™ LAA occlusion device (Corherex Medical, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), Lariat® (SentreHEART, Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA).

Suggestions for management

In summary, this is a 68-year-old male with a severe/life-threatening gastrointestinal bleed from caecal angiodysplastic lesions on aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin. The patient is at high risk for both AFib associated stroke and re-bleeding, but at relatively low risk for ST. It is important to note that the risk of both re-bleeding and ST will change (improve) over time.

We would continue to hold anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents as the patient is stabilised and encourage the gastroenterology service to proceed emergently with endoscopic haemostasis. We would then start the patient on low-dose aspirin (<100 mg, daily) and clopidogrel (75 mg, daily) for three months. If without recurrence, we would then stop the clopidogrel, continue low-dose aspirin and restart anticoagulation with a direct thrombin inhibitor or Factor Xa inhibitor to reduce the likelihood of the further wide variations of cascade inhibition which occurred in this patient. If only warfarin is available, we would aim for an INR of 2.0-2.5.

LAA closure has the promise of eliminating the need for chronic coagulation cascade inhibition, thus reducing associated bleeding and simplifying the management of patients like this. If available, we would proceed with LAA closure with discontinuation of coagulation inhibition as early as possible followed by aspirin and clopidogrel for a total of six months.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

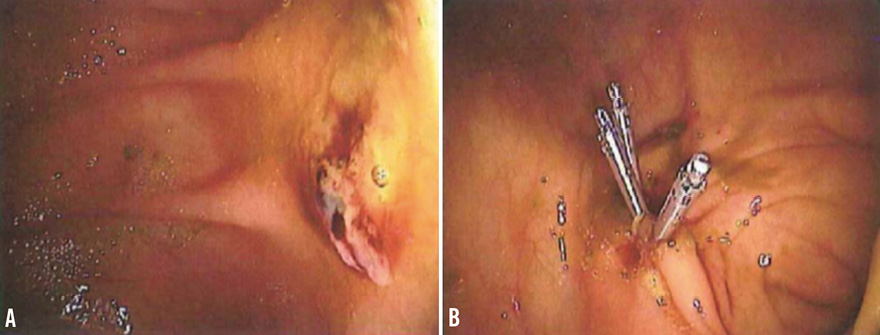

The management of this case was based on a multidisciplinary approach that involved a team of interventional cardiologists and a gastroenterologist with training in endoscopic haemostasis. The patient was treated with endoscopic heater probe thermocoagulation of the caecum angiodysplastic lesions, achieving effective haemostasis. Twenty-four hours after the endoscopic procedure, we decided to resume dual antiplatelet treatment (aspirin 75 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day) only. The patient was discharged two days later on this therapy in good clinical condition. After six days, he again developed severe melaena followed by haemorrhagic shock. On admission, blood pressure was 90/75 mmHg and haemoglobin was 6.2 g/dl. Antiplatelet therapy was stopped, plasma expanders were administered and 4 units of red blood cells were transfused for a second time, obtaining haemodynamic stability, correction of anaemia, and disappearance of symptoms and signs of haemorrhagic shock. Colonoscopy showed that the site of re-bleeding was again the caecal angiodysplastic lesions. The gastroenterologist chose another endoscopic treatment and applied nine metallic endoclips (Resolution clip; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) to the angiodysplastic lesions of the caecum obtaining definitive haemostasis (Figure 3). Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin (75 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) was resumed after 24 hours and the patient was discharged two days later. At nine-month follow-up, he was without symptoms and had no re-bleeding, stent thrombosis or cardioembolic events.

Figure 3. High resolution image of the bleeding vascular lesions before (A) and after endoscopic application of haemoclips (B).

Discussion points

This case is a prototypic example of a serious concern following PCI with drug-eluting stent implantation, namely major GI bleeding due to undetected comorbidities that reveal themselves after double antiplatelet therapy has been initiated. Indeed, this patient had no history of bleeding despite long-standing oral anticoagulant treatment, while massive melaena occurred 12 days after dual antiplatelet therapy was added. The cause of GI bleeding was angiodysplasia of the caecum, a colonic disease with a 0.8% prevalence in healthy patients over 50 years of age undergoing screening colonoscopy20. This condition consists of ectasia of normal intestinal submucosal veins and overlying mucosal capillaries whose wall is formed by endothelial cells and lack a smooth muscle cell layer21. Overall, caecal angiodysplasia is the second leading cause of lower GI bleeding after diverticulosis in patients older than 60 years: it accounts for approximately 6% of lower GI bleeds. Blood loss is usually low grade, but massive and life- threatening haemorrhage occurs in approximately 15% of patients. However, caecal angiodysplasia is not the most common reason for GI bleeding in coronary artery disease patients. Chin et al reported that the most frequent sources of upper GI bleeding, among 5,673 PCI patients, were equally likely to be located in the stomach or oesophagus (40% and 36%, respectively), followed by the duodenum (22%)22. Bleeding occurred in 1.2% of patients at a mean time of 2.8 days post treatment, and was most commonly due to gastric erosion (20.2%), duodenal ulcer (14.3%), gastric ulcer (13.1%), oesophagitis (13.1%), or Mallory-Weiss tear (13.1%)22. Concerning lower GI bleeding, a study in 100 patients undergoing colonoscopy within 30 days of myocardial infarction showed that the most common causes of haemorrhage were ischaemic colitis, colon cancer, internal haemorrhoids, pseudomembranous colitis, and adenomatous polyps23.

Irrespective of the source of bleeding, analyses from randomised trials, meta-analyses, and registries reveal a significant association between major bleeding and increased mortality in patients undergoing PCI23. Several mechanisms other than the location (intracranial) or massive nature of haemorrhage (gastrointestinal, retroperitoneal) may link bleeding with increased mortality in this clinical setting. Among them, rebound ischaemic events due to cessation of antithrombotic therapies and activation of clotting, adverse impact of hypotension, and the presence of common risk factors for both bleeding and adverse outcome may have specific detrimental effects24. Moreover, emerging evidence indicates that red blood cell transfusion, which is frequently needed when major bleeds occur, is associated with increased in-hospital and one-year mortality in patients who have recently undergone PCI25-27.

Although right haemicolectomy has been used in patients with caecal angiodysplasia28, endoscopic treatment of bleeding vascular lesions with heater probe, argon laser coagulation, injection sclerotherapy, or mucosal resection is an effective and significantly less invasive therapeutic strategy to obtain cessation of recurrent bleeding29,30. In our patient, however, re-bleeding occurred several days after heater probe coagulation, whereas endoscopic clipping was very effective in providing haemostasis in the presence of dual antiplatelet therapy. Indeed, the potential value of this approach was demonstrated in the report of a patient with caecal angiodysplasia and atrial fibrillation hospitalised for acute myocardial infarction31. Preventive endoclip application to the vascular malformation site and cauterisation were performed 24 hours prior to coronary stent placement. The patient was discharged on clopidogrel, aspirin, and warfarin without any bleeding during a follow-up of 11 months. Endoclips have proved to be a valuable alternative method in many other forms of GI tract bleeding controlling haemostasis using mechanical pressure32.

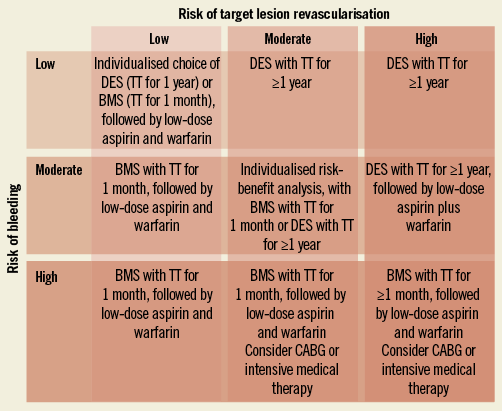

Our case belongs to the expanding group of patients in whom chronic oral anticoagulation with warfarin is clinically warranted and who also need PCI. These patients present unique clinical challenges. The conundrum for the interventional cardiologist is the delicate balance of preventing ischaemic events, particularly stent thrombosis, while reducing the risk of stroke and other cardioembolic events with oral anticoagulation therapy and avoiding an unacceptably high haemorrhagic risk. Although appropriate treatment algorithms for these patients have not been clearly established, potential strategies can be derived from small single-centre experiences and retrospective registries. However, these studies were not primarily designed to assess triple therapy. Recently, Zinn and Feit reviewed the literature and reported that patients who undergo coronary artery stenting and receive triple therapy have higher rates of major and minor bleeding, blood transfusion, and probably fatal bleeding as compared to similar patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy only33. On the other hand, data regarding the impact of triple therapy are conflicting and do not show a clear benefit in terms of major adverse cardiac event rates. This is not unexpected because the reduction in embolic and thrombotic complications may be offset by the well-known increase in composite ischaemic events occurring in patients who develop bleeding complications. The same authors proposed an algorithm for the selection of antithrombotic strategies for patients undergoing coronary stenting in whom there is a compelling need for warfarin (Figure 4)33. This algorithm may help in making the clinical decisions between drug-eluting stents and bare metal stents, and dual antiplatelet therapy versus triple therapy. Choice of therapy is based on the individual patient’s risk of bleeding and in-stent restenosis; in patients with a low risk of embolic complications, oral anticoagulation could be withheld if risk factors for bleeding are present as long as dual antiplatelet therapy is needed according to current guidelines34.

Figure 4. A proposed treatment algorithm for selection of early and late antiplatelet and warfarin therapy and selection of bare metal stents (BMS) vs. drug-eluting stents (DES) based on individualised risk profile for bleeding and restenosis (modified from ref. 14). TT: triple therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin)

After bleeding events, we decided to treat our patient with dual antiplatelet therapy only. This decision was based on the remaining significant risk of bleeding compared to the risk of vascular events due to atrial fibrillation. Indeed, he had a CHADS2-VASc score of 4 that is associated with an estimated annual stroke risk of 4% (95% CI: 3.1-5.1) in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation patients35. Moreover, the event rate when clopidogrel is added to aspirin is much lower than that observed in patients on aspirin alone. The ACTIVE A trial compared clopidogrel to placebo in atrial fibrillation patients at high risk of stroke concomitantly receiving aspirin36,37. The stroke rate with aspirin plus clopidogrel was 2.4% per year, a value less than half that seen in SPAF 3 with aspirin37. In conclusion, even though there is still a significant relative difference in stroke rate (relative risk 1.72) between aspirin plus clopidogrel and oral anticoagulation, the absolute difference in all stroke events is only 1% per year and that of disabling strokes is less than 0.5% per year12.

Conflict of interest statement

A.L. Bartorelli has received minor honoraria from and is an advisory board member for Abbott Vascular. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.