Abstract

Aims: To evaluate crude cardiovascular risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who are on oral anticoagulants (OAC) after percutaneous coronary intervention with stents (PCI-S) and also to evaluate if the patients on OAC after PCI-S benefit from clopidogrel.

Methods and results: Data from RIKS-HIA and SCAAR on patients admitted to coronary care units 1997 to 2005, undergoing PCI-S (n=27,972), were evaluated. OAC were prescribed to 4.2% (n=1,183) of the patients and they had higher crude 1-year mortality than the non-OAC group, (3.6% [n=42] vs. 1.5% [n= 413], p=0.008), but after adjusting for pre-treatment patient characteristics there were no significant difference in 1-year mortality (adjusted risk ratio [adj. RR] 0.82 [95% CI 0.58-1.16]). Of patients on OAC, 56% (n=659) were also on clopidogrel at discharge. Incidence of death or myocardial infarction (MI) within one year did not differ between the clopidogrel and non-clopidogrel group, adj. RR 0.93 (95% CI 0.65-1.34). Triple therapy (OAC, clopidogrel plus aspirin) was associated with four times higher risk of any bleeding than OAC plus aspirin, adj. RR 4.27 (95% CI 1.2-15.1) but a lower incidence of death or MI than OAC plus clopidogrel adj. RR 0.63 (95% CI 0.40-0.99)

Conclusions: Patients discharged on OAC after PCI-S in ACS have higher crude 1-year mortality than patients not on OAC, largely explained by age and comorbidities. Adding clopidogrel is not associated with lower incidence of death or MI at one year. Triple therapy is associated with higher risk of any bleeding than OAC plus aspirin but lower risk of death or MI than OAC plus clopidogrel.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAT), aspirin and a thienopyridine, is currently the optimal antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting (PCI-S)1-5. Clopidogrel is preferred to ticlopidine because of better tolerability and fewer side effects6. Also, long-term treatment with clopidogrel is beneficial after PCI in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (ACS)7. In patients undergoing PCI-S also requiring oral anticoagulants (OAC) due to conditions such as atrial fibrillation (AF), venous thromboembolism and prosthetic heart valve, the optimal antithrombotic strategy is not known. The recent published consensus document on “Management of Antithrombotic Therapy in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention/Stenting”8 is based on small, single-centre, retrospectively analysed cohorts. Larger registers and prospective clinical trials are needed.

Aspirin in combination with clopidogrel is inferior to OAC alone in preventing vascular events in patients with AF9. OAC and clopidogrel in combination, with or without aspirin, after PCI-S has not been studied in any randomised trial, thus both safety and efficacy for the combination is unknown. Patients with an indication for OAC after PCI-S have an unsatisfactory long-term prognosis compared to patients without indication for OAC10 and OAC plus aspirin is insufficient in preventing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) after PCI-S1-4. From this perspective we hypothesised that: 1) patients on OAC after PCI-S have a higher overall cardiovascular risk and 2) that use of clopidogrel is beneficial.

Methods

Study population

Data from The Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admission (RIKS-HIA) and the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Register (SCAAR) were merged to conduct this study. All patients who were discharged alive from coronary care units (CCUs) 1997-2005, who had undergone PCI-S during the hospital stay and for whom complete follow-up data were available from the National Population Register and the Swedish Hospital Admission Register were included in the study (n=27,972).

RIKS-HIA

RIKS-HIA includes information on all patients admitted to Swedish CCUs. Information on patient care is entered into the RIKS-HIA by case record forms that include about 100 variables as described elsewhere11. The complete protocol is available at www.riks-hia.se. Data is verified every year by an external monitor who compares the register information with the original hospital records in randomly selected patients from about 20 different hospitals. The agreement between the registered information and patient records have varied between 94% and 96%.

SCAAR

Since 2001, SCAAR includes data on all patients treated at PCI-centres in Sweden. Monitoring of the register data have been performed annually by comparing 50 entered variables in 20 randomly selected interventions per hospital and year with the patients’ hospital records. The overall correspondence in data has been 95.2% since 2003.

Data definitions and follow-up

The SCAAR and RIKS-HIA databases were merged with the National Population Register for data on vital status and time of death. Bleeding events, myocardial infarction (MI) and ischaemic stroke were defined by disease codes according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) as reported to the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register for hospital admissions. MI was defined by disease codes I21-I23 or data from case records in RIKS-HIA. Ischaemic stroke was defined by disease code I63. Intracranial haemorrhage (ICH), major bleeding and any bleeding requiring hospitalisation was defined by ICD-10 disease codes reported in Suppl. Table S1. Merging of the databases was performed by the Epidemiologic Centre of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and based on the personal identification number of each Swedish citizen. The study was approved by the local ethics committees at Uppsala University and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Statistical analysis

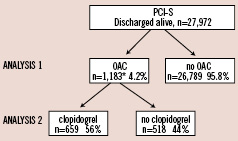

Two analyses were done; the first analysis evaluated OAC vs. no OAC, and the second analysis evaluated clopidogrel vs. no clopidogrel in the subset of OAC patients (Figure 1). The primary objective for the first analysis was 1-year mortality. Secondary objectives were any bleeding requiring hospitalisation, major bleeding, ischaemic stroke, ICH and two composite endpoints; death or MI, and net clinical outcome (death, MI or any bleeding). The primary objective for the second analysis was the incidence of death or MI at one year. Secondary objectives were 1-year mortality, any bleeding requiring hospitalisation, major bleeding, ischaemic stroke, ICH, and net clinical outcome. Cox-regression models adjusting for confounders, using propensity score methods12 were used to compensate for imbalances in the baseline characteristics, possibly associated with treatment decisions. The propensity-score was defined as the conditional probability of receiving treatment (OAC in the first analysis; clopidogrel in the second analysis) given all available pre-treatment patient characteristics (variables in appendices) and were estimated with a logistic regression model and subsequently entered as a covariate in the Cox-regression models. A statement of “significance” implies statistical significance at the 5% level and all reported p-values are two sided.

Figure 1. Patients’ selection procedure. RIKS-HIA: Register of Information and Knowledge About Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions; SCAAR: Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Register; PCI-S: percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation; OAC: oral anticoagulants. *Data on clopidogrel at discharge is missing in six patients.

Results

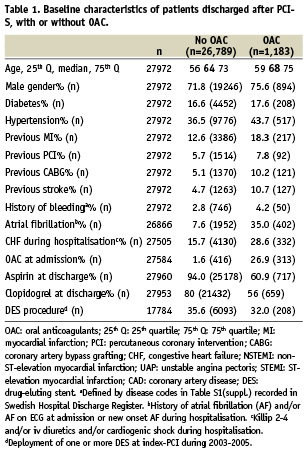

Outcome after PCI-S with or without OAC

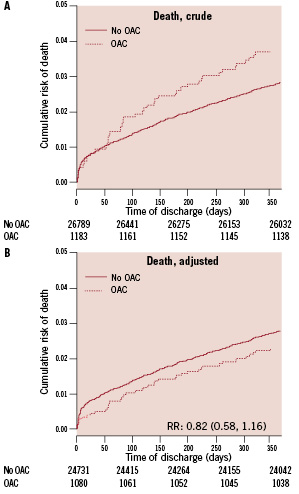

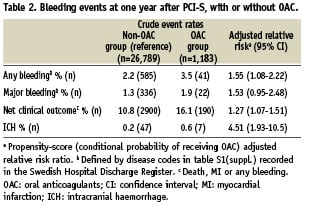

A total of 27,972 patients were discharged alive after PCI-S of whom 4.2% (n=1,183) were prescribed OAC and 90% (n=25,091) had PCI-S during hospitalisation due to ACS. Patients on OAC were older, more often men, more likely to have hypertension, AF and CHF than patients not on OAC (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2). They were also more likely to have experienced an MI, and to have been treated with coronary revascularisation prior to the index hospitalisation. Furthermore they were less likely discharged with antiplatelet agents, clopidogrel and aspirin. Patients on OAC had higher crude 1-year mortality than the non-OAC group (Figure 2A) but after adjustments for baseline characteristics, the difference in 1-year mortality was no longer evident (Figure 2B). Incidence of death or MI at one year is higher in the OAC group after adjustments (adj. RR 1.20 [95% CI 1.00-1.45]). Ischaemic stroke after discharge was more common in the OAC group than in the non-OAC group, (adj. RR 1.60 [95% CI 1.09–2.34]). Patients in the OAC-group had a higher rate of any bleeding requiring hospitalisation, higher incidence of intracranial bleeding, and higher incidence of net clinical outcome at one year (Table 2).

Figure 2. Mortality after PCI-S in patients with acute coronary syndrome with or without OAC. A: unadjusted mortality for one year of follow-up. B: represents the estimations of mortality rates from the Cox regression model at the mean level of propensity score defined as the conditional probability of receiving OAC. OAC: oral anticoagulants; RR: adjusted relative risk ratio (95% confidence interval)

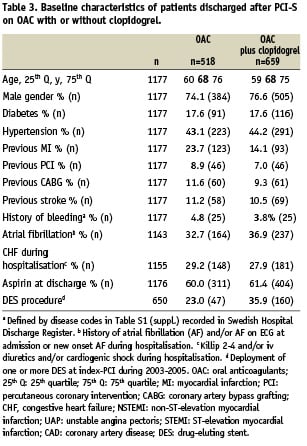

Outcome after PCI-S on OAC with or without clopidogrel

Fifty-six percent (n=659) of the patients on OAC (n=1,183) were prescribed clopidogrel at discharge. Six patients were excluded from further analysis because of missing data on clopidogrel at discharge. Patients on clopidogrel were less likely to have had a previous MI, previous coronary revascularisation and history of heart failure (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3). Aspirin use was equivalent in the clopidogrel and the non-clopidogrel group. Deployment of one or more DES during index-PCI was more common in the clopidogrel group.

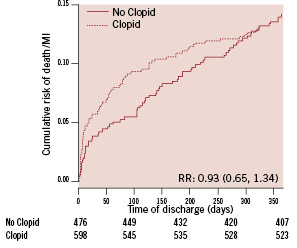

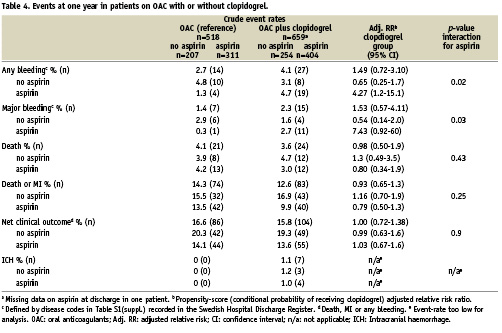

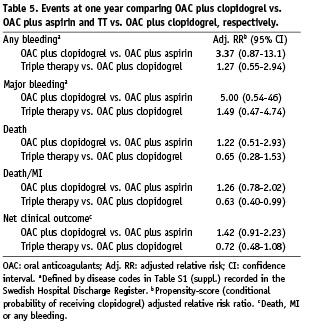

There was no difference in incidence of the combination of death or MI at one year between the two groups after adjustments (Figure 3). No significant difference was seen in mortality or net clinical outcome at one year (Table 4). ICH was evident only in the clopidogrel group. Interaction with aspirin was found in any bleeding and major bleeding at one year. Patients receiving triple therapy (TT [OAC, clopidogrel plus aspirin]) had a four times increased risk of any bleeding than patients on OAC plus aspirin (Table 4). A post hoc analysis of adj. RR for outcomes between OAC plus clopidogrel vs. OAC plus aspirin and TT vs. OAC plus clopidogrel, respectively is presented in Table 5. TT was associated with decreased risk of death or MI compared to OAC plus clopidogrel.

Baseline characteristics of the four subgroups of combinations of antiplatelet agents added to OAC are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

Figure 3. Incidence of death or MI after PCI-S in patients on OAC with acute coronary syndrome with or without clopidogrel. Estimations from the Cox regression model at the mean level of propensity score, defined as the conditional probability of receiving clopidogrel. Clopid: clopidogrel; RR: adjusted relative risk ratio (95% confidence interval)

Outcome after PCI with DES on OAC with or without clopidogrel

There was no difference in incidence of death or MI at one year between the clopidogrel group and the non-clopidogrel group in a subgroup analysis of subjects undergoing PCI with DES deployment (n=207), (adj. RR 0.71 [95% CI 0.44-1.15]). Neither was there any difference in any bleeding at one year (adj. RR 1.16 [95% CI 0.46-2.92]).

Discussion

Treatment with oral anticoagulants after PCI-S

In this multicentre register-study, prospectively including consecutive patients with ACS in every day practice, we conclude that patients on OAC after PCI-S have higher crude 1-year mortality than patients not on OAC. However, OAC treatment itself is not associated with higher mortality, which is thus associated with age, comorbidities and possibly inadequate antithrombotic therapy. Incidence of any bleeding requiring hospitalisation, net clinical outcome and ICH on the other hand is higher in the OAC group compared to the non-OAC group, which cannot be explained only by comorbidities and age alone, but by OAC itself.

A recent publication from North America reported that only 30.5% of patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI during hospitalisation due to ACS were discharged with OAC13. In a study by Ruiz-Nodar et al on patients with AF who underwent PCI-S with DES (n=426), OAC was associated with reduced mortality compared to different antiplatelet regimens, mainly DAT14. There was a non-significant increase in bleeding (14.9% vs. 9.0%; p=0.19) associated with OAC treatment. Hälg et al reported a nine times higher risk of major bleeding after discharge from hospital in patients on OAC (n=44) compared to single or dual antiplatelet therapy (n=769) in the BASKET population15. Sarafoff et al evaluated the use of echocardiographical criteria, in patients with an indication for OAC (n=515), to determine antithrombotic strategy after PCI-S with DES in a non-randomised observational manner16. Triple therapy vs. DAT, for most patients four to 12 weeks, followed by OAC and aspirin indefinite, had a non-significant lower incidence of death, MI, stent thrombosis or stroke at two year (14.1% vs. 18.0% OR=0.76, 95% CI 0.48–1.21; p=0.25). Karjalainen et al reported that 239 patients on OAC undergoing PCI-S had an unsatisfactory prognosis and within the group of patients with an indication for OAC, DAT was associated with 8.8% stroke at one year compared to 2.8%, 3% and 0% for TT, OAC plus aspirin and OAC plus clopidogrel, respectively10. Although the differences were not statistically significant it is in agreement with randomised data which showed OAC to be superior to DAT for prevention of vascular events in patients with AF9. In aggregate, now available data, suggests that patients with an indication for OAC undergoing PCI-S due to ACS are at higher future risk for cardiovascular events and stroke and should be discharged on OAC, despite a higher risk of bleeding.

Clopidogrel in patients on oral anticoagulants after PCI-S

The second principal finding of our study is that in patients with ACS, the use of clopidogrel after PCI-S in patients on OAC is not associated with lower incidence of death or MI at one year. The incidence of any bleeding at one year in the clopidogrel group is dependent on aspirin use. Patients on TT have a fourfold higher risk of any bleeding than patients on OAC plus aspirin at one year and only a modest increase in risk of any bleeding compared to OAC plus clopidogrel. Furthermore, TT is associated with lower incidence of death or MI compared to OAC plus clopidogrel. Patients on OAC plus clopidogrel have a higher bleeding rate at one year than patients on OAC and aspirin, although not statistically significant. The clinical implication of our data is that if TT is not thought to be tolerated due to increased risk of bleeding, 1) withdrawal of clopidogrel will reduce risk of bleeding more than withdrawal of aspirin and 2) withdrawal of aspirin is associated higher risk of death or MI.

Now available data on adding antiplatelet agents to OAC after PCI is inconsistent. Karjalainen et al reported that the combination of OAC plus aspirin had a high rate of stent thrombosis, 15.2% as compared to 1.9%, 0% and 5,9% for TT, OAC plus clopidogrel and DAT, respectively, p=0.00410. An observational study from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events investigated the use of single antiplatelet agent in combination with OAC (n=220) vs. TT (n=580) after PCI-S and could not show any difference in 6-month mortality17. In the single antiplatelet group, the use of either aspirin or thienopyridine in combination with OAC resulted in similar incidence of death and MI but there was a trend to a higher risk of unscheduled PCI for OAC plus aspirin (17.2% vs. 7.9%, p=0.06).

Previous studies have reported major bleeding rates ranging from 1.4% to 21% at one year10,14,16,18-25 associated with TT. Our study is, to our knowledge, the largest report with long-term follow-up reporting safety on TT (n=404). Major bleeding rates are at reasonable levels when TT is prescribed at physician’s discretion, albeit risk of ICH of 1.0% at one year must be taken into account.

Randomised studies addressing the antithrombotic treatment in PCI-patients requiring OAC are under way; six weeks vs. six months of TT after DES implantation26 and OAC plus clopidogrel vs. TT27. These studies will provide important data on the topic.

There are probably unknown important factors that might exert negative influence on efficacy outcome in the clopidogrel group. We lack appropriate data on lesion complexity up to 2004. It is likely that clopidogrel use is associated with more complex lesions, e.g., longer lesions and bifurcation lesions, which increases the risk of stent thrombosis28 and subsequently the risk of death or MI. Secondly, physicians might have been more prone to discontinue clopidogrel earlier than aspirin since randomised data on OAC plus aspirin have been evident1-4,29,30 but none or only sparse observational data have been available on OAC plus clopidogrel when a majority of index-PCI in this study were performed. Premature discontinuation of antiplatelet agents, clopidogrel or aspirin have been associated with stent thrombosis28,31,32 and could compromise the clopidogrel group.

There are important general study limitations. Indication for OAC is unknown and duration of OAC after discharge is not known although we expect that most patients discharged with OAC are on continuous medication during follow-up or until an event. Also, the PK-INR is not known at the time of bleeding. Several endpoints apart from the primary objectives have been reported and risk of type I error due to multiple testing should be acknowledged. There are also major strengths in this study. All data is collected prospectively. The databases RIKS-HIA and SCAAR are both recognised for high quality and including consecutive unselected high number of patients representing the everyday practice. Furthermore, this is, to our knowledge, the largest study with long-term follow-up on OAC plus clopidogrel after PCI-S in ACS.

Conclusions

Patients with ACS discharged on OAC after PCI-S have higher crude 1-year mortality than patients not on OAC, largely explained by age and comorbidities. Adding clopidogrel, at the physician’s discretion, is not associated with lower incidence of death or MI at one year. Triple therapy with OAC, clopidogrel and aspirin is associated with a fourfold higher risk of any bleeding than OAC plus aspirin but a lower risk of death or MI than OAC plus clopidogrel. Randomised studies are warranted to determine the optimal duration as well as combination of antithrombotic therapy after PCI-S in patients requiring OAC in ACS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Database Manager Sören Gustafsson at UCR, Uppsala for his excellent work with the databases.

Funding

This paper was funded by Filip Lundbergs foundation/Eirs 50-years foundation and Anders Otto Swärds foundation/Ulrika Eklunds foundation. RIKS-HIA and SCAAR is sponsored by the Swedish Health Authorities and is independent of commercial funding.