Abstract

Aims: The purpose of this study was to evaluate factors that contribute to a patent IRA (infarct - related artery) and the prognostic impact of a patent IRA in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Methods and results: Using the Swedish angiography and angioplasty registry (SCAAR) we included all patients with STEMI and one-vessel coronary artery disease who underwent primary PCI of the culprit lesion only from May 2005 to December 2007. A patent IRA was found in 1,104 of 3,284 patients. Patients with an occluded IRA had significantly increased 7-day mortality (HR, 3.03, 95% CI 1.68-5.46, P<0.001). The incidence of an occluded IRA increased with higher age, in patients over 80 years of age (OR, 1.23, 95% CI; 0.92-1.64), lower in patients on lipid-lowering drugs (OR, 0.68, 95% CI; 0.54-0.86) and lower in patients pre-treated with heparin (OR 0.71, 95% CI; 0.60-0.83) or GPIIb/IIIa receptor blockade (OR 0.77, 95% CI; 0.61-0.97). Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel had no effect on IRA patency.

Conclusions: IRA patency was associated with a lower 7-day mortality. Older STEMI patients and patients not taking lipid-lowering drugs or pre-treated with heparin or GPIIb/IIIa receptor blockers seem to constitute risk groups for having an occluded IRA.

Introduction

Prior to the introduction of primary angioplasty (PCI) for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) it was demonstrated in several large-scale clinical trials that patients with AMI receiving thrombolytic therapy have a better prognosis compared to non-thrombolysed patients.1-3 Patients with AMI fulfilling electrocardiographic or angiographic criteria for reperfusion following thrombolytic therapy had a more favourable prognosis compared to AMI patients without signs of reperfusion.4,5

The experiences from thrombolysis studies have served as a stepping-stone for the understanding and development of treatments for AMI including PCI. Primary PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is superior to thrombolysis in terms of cardiac outcome and death.6-8 Stenting of an IRA (infarct - related artery) is superior to angioplasty without stenting and reduces re-occlusions after the procedure.9,10,25 Symptom-to-reperfusion time needs to be as short as possible in order to minimise morbidity and mortality.11

When a patient with STEMI arrives in the catheterisation laboratory he or she has typically received antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and clopidogrel as well as anticoagulant therapy with heparin. Thus, quite a few patients arrive with a patent, although stenosed, IRA. There is evidence to suggest that some patients undergo early spontaneous reperfusion with widely varying reported incidences from 4% to 57% of patients.12-14 This variation may be explained by differences in timing of the assessment, whether the study related to angiographic findings or electrocardiographic ST segment resolution, the duration of symptoms and different definitions of spontaneous reperfusion. However, spontaneous reperfusion (equalling a patent IRA) has been shown to be an independent predictor of myocardial salvage, PCI success, and improved outcome.12-14

The present study of patients with STEMI had two major objectives: 1) to determine factors of importance for a patient to arrive in the catheterisation laboratory with a patent IRA; and 2) to assess the prognostic importance of a patent versus an occluded IRA at coronary angiography following STEMI. We used the nationwide Swedish angiography and angioplasty registry (SCAAR), which include all patients undergoing PCI in Sweden, to address our objectives.

Methods

Study population

Our study included all patients registered in SCAAR with STEMI and angiographically verified one-vessel coronary artery disease that underwent primary PCI of the culprit lesion only from May 2005 to December 2007. All patients were followed-up until April 14, 2008.

SCAAR data

SCAAR holds data on consecutive patients from all centres that perform coronary angiography and PCI in Sweden. The registry is sponsored by the Swedish Health Authorities and is independent of commercial funding. The technology is developed and administered by the Uppsala Clinical Research Centre. Since 2001, SCAAR has been Internet-based, which provides each centre with immediate and continuous feedback on processes and quality-of-care measures. Monitoring and verification of registry data have been performed in all hospitals since 2001 by comparing 50 entered variables in 20 randomly selected interventions per hospital and year with the patients’ hospital records. The overall correspondence in data during the study period was 95%.

In the SCAAR database, information about stenosis severity is entered before PCI. One hundred percent stenosis denotes an occluded coronary artery. We defined a patent IRA as a stenosis severity of any percentage less than 100%.

In the SCAAR registry, STEMI is defined as ST elevation and/or new LBBB in patients with a relevant history. Symptom onset and symptom duration was not registered systematically in SCAAR in the study period.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to evaluate occluded artery at primary PCI (yes/no) with respect to patient characteristics and antithrombotic medication prior to PCI. Measures of association were odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Both unadjusted and adjusted models were fitted.

To evaluate the effect of occluded artery at primary PCI (yes/no) on all cause mortality we used Cox regression. Risk time was measured from primary PCI to death or end of follow-up, April 14, 2008. Unadjusted and adjusted models were fitted to adjust for patient characteristics and antithrombotic medication prior to PCI. Measures of association were hazard ratios (HR) supplemented with 95% CI. Because of violation of the proportional hazard ratio assumption we also analysed the data in two steps; primarily from primary PCI up to seven days and secondly from seven days (if the patient had survived) to the end of follow-up. P<0.05 was regarded as statistical significant.

Unadjusted and adjusted models were fitted to adjust for patient characteristics and antithrombotic medication prior to PCI. Measures of association were hazard ratios (HR) supplemented with 95% CI. Because of violation of the proportional hazard ratio assumption we also analysed the data in two steps; primarily from primary PCI up to seven days and secondly from seven days (if the patient had survived) to the end of follow-up.

Results

Patients characteristics

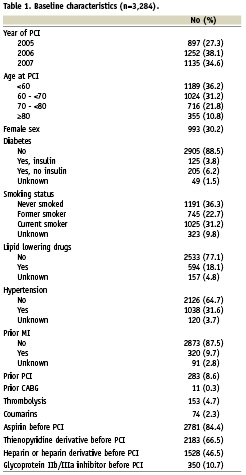

In total, 3,296 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, but 12 patients (0.3%) were excluded because of incomplete registration. Thus 3,284 patients were included in the study. Mean follow-up time was 1.6 years (SD 0.8, range one day to three years). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the patients included. Less than one-third of patients were women, and less than one-third were current smokers, while 10% had diabetes mellitus. A little less than 5% of patients had received thrombolysis. It is not possible from the SCAAR database to decode how many of the patients who received thrombolysis had received this therapy as intention-to-treat (e.g., participants in clinical studies) and how many patients who were referred to the catheterisation laboratory for rescue PCI. Of the lesions, 34.1% were found in the RCA, 50.5% in the LAD, 12. 9% in the LCX, 1% in the IMA and 1.6% in the PLA. PCI was evaluated to have been successful in 98.4% of patients in the patent IRA group, as opposed to 94.2% in the occluded IRA group. In the patent IRA group 95.7% were stented compared to 91.0% in the occluded IRA group.

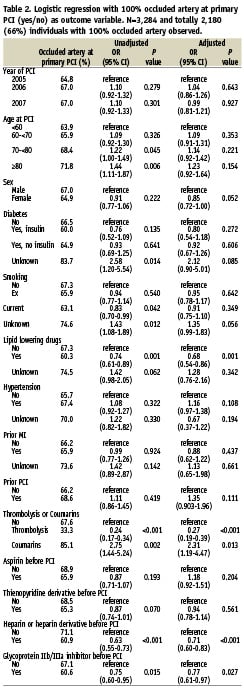

Occluded artery at primary PCI

Roughly two-thirds of patients (2,180 out of 3,284) had an occluded IRA at PCI (Table 2). Old age was a predictor of an occluded IRA. There was an insignificant trend for men to have a higher incidence of occluded IRA compared with women. Patients taking lipid-lowering drugs had a lower incidence of occluded IRA compared with patients not taking these drugs. Thrombolysis, oral anticoagulants, heparin or heparin derivatives as well as glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists were all associated with a lower incidence of occluded IRA while ASA and clopidogrel were not.

Mortality

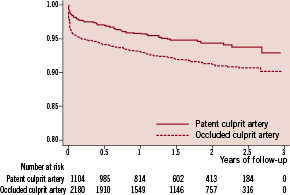

Patients with an occluded IRA had a threefold increased risk of dying within the first seven days post MI compared to patients presenting with an open IRA (3.5% vs. 1.2%, HR 3.03 [95% CI 1.68-5.46], P=0.001). From day seven to day 912 there was no difference in mortality (4.7% in the occluded IRA group and 4.0% in the patent IRA group, HR 1.17 [95% CI 0.82-1.67], P=0.39). A Kaplan-Meier survival curve is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curve illustrating mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and an occluded infarct-related coronary artery at arrival in the catheterisation laboratory and in patients with a patent infarct-related coronary artery. Patients with an occluded artery had a significantly increased risk of dying within the first seven days (3.5% vs. 1.2%, HR 3.03 [95% CI 1.68 - 5.46], P<0.001).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study of patients with STEMI and one-vessel coronary artery disease were that a patent IRA at arrival in the catheterisation laboratory was associated with a lower 7-day mortality. Patients with an occluded IRA at arrival had a threefold increased risk of dying within the first seven days after the myocardial infarction. Older patients and patients not taking lipid-lowering drugs or being pre-treated with heparin or GPIIb/IIIa receptor blockers seem to constitute risk groups for having an occluded IRA in conjunction with STEMI.

The finding that only 91% of patients with occluded IRA underwent stent treatment, as opposed to 95.7% with patent IRA, could be explained by the fact that the lesion could not be wired, by difficulties advancing a stent resulting in angioplasty only and that some lesions were treated by angioplasty only on the operators discretion.

Our findings underline the clinical notion from PCI that “time is myocardium”. Following acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction at arrival in the catheterisation laboratory, even a 99% stenosis predicts a survival benefit compared to a completely occluded culprit coronary artery. The most likely chain of events in patients with a patent IRA, is that the artery occluded coincides with the patient having symptoms and that the IRA later opened as a result of spontaneous reperfusion12-14, pre-medication (heparin or heparin derivatives, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists) or a combination.15-17

Recent studies investigating spontaneous reperfusion are in agreement with our findings in how much patients benefit from a patent IRA before PCI.12-14 Myocardial salvage is improved, patients have fewer complications and reinfarction is rarer. Some of the data even suggest that early PCI might not be the best treatment for STEMI patients with an open IRA.13

An important finding of our study is that patients on lipid-lowering medication had a significantly higher likelihood of having a patent IRA. This finding is in line with a small retrospective study.18 A possible explanation for this could be ascribed to the pleiotropic effects of statins such as a direct antithrombotic effect via inhibition of platelet CD40L and CD40L-mediated thrombin generation19, an up-regulation of nitric oxide synthase20 or inhibition of plaque rupture.21

Less surprisingly, we also found a positive effect of heparin or heparin derivatives and of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists on IRA patency. This is in accordance with earlier findings showing the effectiveness of heparins in acute coronary syndromes as addressed in the FRISC and ASSENT-3 randomised trials22,23 and the effect of glycoprotein antagonism as demonstrated in the ADMIRAL study.24

We could not demonstrate a statistically significant effect of ASA on IRA occlusion. While the benefit of ASA in myocardial infarction has been indisputably shown in many large trials, such as ISIS-2,3 it may be that the beneficial effect of ASA treatment is more pronounced over a longer period of time (ISIS-2: 35 days follow-up). Randomised clinical trials like CAPRIE and CURE26,27 showed that clopidogrel reduces cardiovascular mortality significantly. The CREDO trial28 established that adding clopidogrel to ASA post-PCI did not significantly increase major or minor bleedings, although an association with an increase in gastrointestinal bleedings did occur. Our study did not show a significant benefit of clopidogrel/ ticlodipine in terms of patent IRA at primary PCI. However, in the CURE trial27 a statistically significant benefit was seen regarding death and MI within the first 24 hours following clopidogrel administration. A recent retrospective study showed that initial coronary artery patency and clinical outcome were improved following pre-treament with clopidogrel in elective patients with non-ST-elevation coronary syndromes.29 It needs to be emphasised that even patients who receive ASA or clopidogrel only minutes before PCI, where a clinically relevant effect on IRA is negligible, will be registered as pre-medicated with these drugs in SCAAR. Accordingly, timing of angiography after clopidogrel may explain the differences between previous studies and our findings.

Thirty-day all-cause mortality in our study was 3.5%, and this is lower than the mortality in large PTCA versus thrombolysis studies like C-PORT (5.3% at six weeks follow-up) and DANAMI-2 (6.6% at 30 day follow-up).30,31 However, in contrast to these studies, we studied patients with one-vessel coronary artery disease only, and this most likely explains differences in survival.

Important and unavoidable limitations are associated with the interpretation of registry data. Despite appropriate statistical adjustments, there could remain differences in baseline characteristics or selection criteria that might not have been recorded. It is a potential problem in the interpretation of data that we included patients with one-vessel disease only. Our rationale was to avoid uncertainty about which lesion was the culprit lesion but we cannot exclude that findings in patients with multivessel disease might differ. Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade of the IRA was not available in this registry study but could have provided more graded information on reperfusion injury in relation to both pre-medication and outcome. Furthermore, time is of major importance when studying spontaneous reperfusion, and the longer the time to PCI, the higher the possibilities to observe an open artery. Likely, the presence of spontaneous reperfusion in early comers has a more important prognostic relevance that in late comers but, unfortunately, information about symptom-to-needle time was not provided from the database at the time the study was conducted. On the positive side, one might argue that when our more inaccurate surrogate variable of flow or not (occluded vessel [100% stenosis] or open vessel [≤99% stenosis]) came out statistically significant for the hardest of endpoints, death, we might have a point. In daily day clinical work, an occluded or patent IRA is a much more applicable parameter for risk stratification than are TIMI flow grade or ST segment resolution. We will pursue this in future studies.

Death in this study is all-cause death. The specific diagnosis or cause of death is not registered in SCAAR and any potential differences between the two groups cannot be reported.

We conclude that achieving pre-PCI IRA patency is of utmost importance to patient prognosis. Statins, young age and pre-treatment with heparin or GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors were strong contributing factors to IRA patency in this study. Our findings and the findings from previous studies emphasise the need for further research – including randomised clinical trials – on factors promoting early IRA patency and spontaneous reperfusion.