The scenario

So, you are driving along a two-lane road and you suffer a sudden blow-out of one of your tyres. The car veers to the left and to the right, but with great skill you pull over onto the hard shoulder. You call the emergency vehicle services immediately and they tow you to a garage where the tyre is uneventfully changed - there and then. The question is: do you now check all your other tyres for faults (significant or less significant) just in case they need prophylactical changing? Maybe, but probably not routinely, although to do so may prevent a future blow-out, with potentially dire consequences. Maybe you would replace a tyre with a small cut in the rim (what is small?), but not one where the tread was worn but still legal.

So it is with management of multivessel disease that is detected at the time of primary PCI (P-PCI) for STEMI. At the time of P-PCI, we may observe what appears to be an obvious, “significant” lesion in the non-infarct-related artery (N-IRA), although even angiographically significant lesions (70-90%) are flow-limiting in only 80% of patients, according to the fractional flow reserve (FFR) cut-off of <0.81. Non-culprit disease may be angiographically even less obvious (50-70%); then it can be really difficult to know whether the lesion is important or not. Debate continues as to how to assess the importance of any non-culprit disease, how it should be managed and, if thought to need treating, when any such intervention should be undertaken.

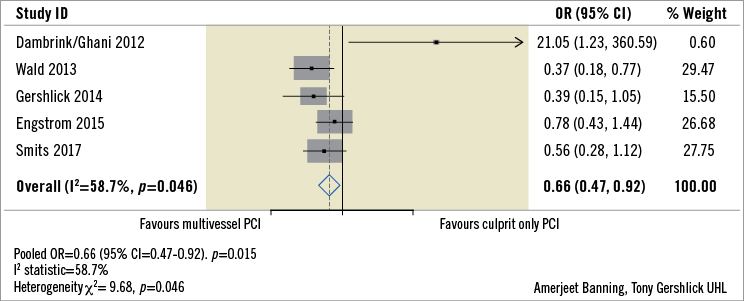

Several small to medium-sized studies and meta-analyses2-7 suggest that treating the N-IRA may be an effective therapeutic strategy, with intervention attenuating the risk of subsequent adverse clinical consequences, albeit that, statistically, the difference has been driven by the need for repeat revascularisation. While there continues to be ongoing debate at major meetings and in the literature about the best approach to this clinical issue, the data so far do support a view that “significant” N-IRA lesions should probably be treated around the time of the P-PCI (i.e., maybe not at the time of the procedure but during that hospital admission). This is supported by the most recent ESC Guidelines (Class IIa LoE A)8. What constitutes significant also remains an open question, with the best case being made for FFR as the modality not only to test for flow limitation, but also maybe as a surrogate for plaque vulnerability9, which is the cause of hard endpoints. Of course, we await the results from three larger trials (Complete vs Culprit-only Revascularization to Treat Multi-vessel Disease After Primary PCI for STEMI [COMPLETE] [NCT01740479]; Ffr-gUidance for compLete Non-cuLprit REVASCularization [FULL REVASC] [NCT02862119]; FLOW Evaluation to Guide Revascularization in Multi-vessel ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction [FLOWER-MI] [NCT02943954]) to help determine whether there is an impact of prophylactic management on hard endpoints, such as death and recurrent MI. Recent propensity-matched registries do suggest benefit in terms of hard endpoint outcomes10 and an updated unpublished meta-analysis by this author and colleagues (Figure 1) supports the potential validity of this strategy on hard endpoints. It has been well established that the outcomes for those with STEMI and multivessel disease (MVD) are worse than for those without MVD11. It would thus seem intuitive –and in keeping with the current data– to undertake complete revascularisation, although some would argue that to do so is not yet absolutely and robustly proven.

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of death or MI from trials randomising STEMI patients with multivessel disease to culprit only or complete revascularisation.

However, there are additional, more subtle issues around non-infarct-related artery disease, including its development, progression, clinical presentation and the factors that influence these phases. The patient is very unlikely to have been fully cured by intervention to the presenting infarct-related artery, irrespective of whether any N-IRA disease is treated or not. Even if the N-IRAs are “completely normal”, this patient has a propensity to develop coronary artery disease. Holistic considerations around secondary prevention have evolved into practical logistics such as mental, emotional and physical rehabilitation, cessation of smoking campaigns and good, instructive communications with the primary care physicians. Assessing the efficacy of any risk factor management may unfortunately be less well done, and merely discharging patients on secondary prevention medication may not be enough. Regular review and a drive towards evidence-based target levels may need to be proactive and prolonged throughout follow-up.

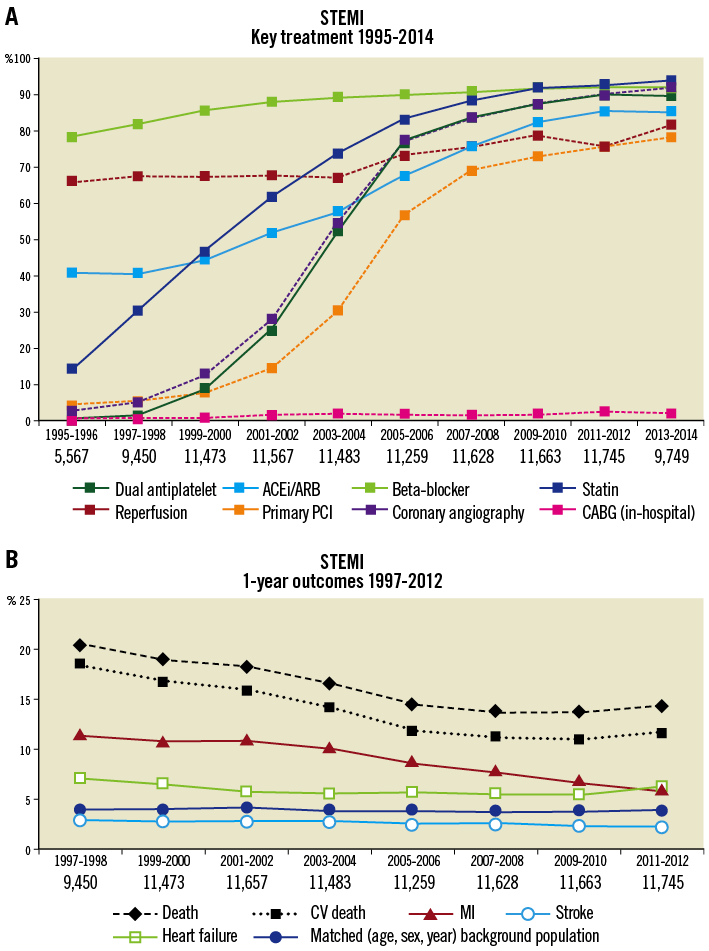

Recently, longer-term registry data have been published which make it clear that patient risk does not end at the point of discharge, in the individual apparently “fit and well” enough to go home, having “got over” their heart attack. For example, there are excellent registry data from the SWEDEHEART group12, who report on the impact of evidence-based, guideline-recommended therapies on outcomes over a 20-year period. These data appear to show a direct correlation between the delivery of evidence-based therapies and improvements in outcome. Thus, the exponential rise in the use of P-PCI from 0% in the mid 1990s to 80% in 2013-14, and the increase in secondary prevention measures from 40% in the mid 1990s to levels of 80-90% in 2013-2014, correlate directly with falls in mortality (from 20% in the mid 1990s to 14% in 2015-2016), in re-AMI (from 12% to 5%), and in the incidence of heart failure (from 7.5% in the mid 1990s to 6% in 2015-16) over the same time period (Figure 2). These direct correlations are indeed impressive and noteworthy. However, while such data certainly make the case for implementation of guideline-directed therapies, they also tell us that there is still work to be done. The hard endpoint event rates at 12 months at these levels (mortality 14%, 5% AMI and 6% heart failure) (Figure 1) require a continuing focus on improvement, not least since the absolute numbers involved mean that residual outcomes are higher than most would consider important from just looking at the percentages. Acute myocardial infarction occurs at a rate of about 50 per 100,000 in Sweden, and 43 to 144 per 100,000 per year in other European countries13. In the USA the rate has decreased from 133 per 100,000 in 1999 to 50 per 100,000 in 200814. Taking an “average” 50 AMI per 100,000 and an EU population of 742,073,853, then in 2017 there were approximately 375,000 STEMIs per annum. Extrapolation from the SWEDEHEART data12 suggests that the absolute contemporary events at 12 months are therefore in the order of 52,000 deaths, 20,000 repeat MI and 23,000 repeat admissions for heart failure. That is a lot of mortality and knock-on morbidity, not even considering those with cardiogenic shock or heart failure at presentation. It would seem that there can be no place for the complacency that may be associated with the satisfaction of achieving TIMI 3 flow in the culprit artery.

Figure 2. Correlation between increase in the use of secondary prevention measures post AMI and falls in adverse event rates over the same period (from the SWEDEHEART registry. Reproduced with permission).

The article from Spitaleri et al in this edition of EuroIntervention thus becomes particularly thought-provoking15.

In their five-year follow-up of the EXAMINATION trial with an excellent 97% patient capture rate, the authors report on subsequent non-target vessel event rates. Fifty percent (50%) of the non-fatal cardiac events were accounted for by non-target events and, although the percentages are small, in the context of absolute numbers as described above, these represent a significant morbidity rate. Even more importantly, from this publication we have some idea of those most at risk. The baseline characteristics that were seen significantly more commonly in those with non-target vessel-related events included not only the presence of MVD and incomplete revascularisation, but also diabetes and hypertension, with diabetes and incomplete revascularisation being independent predictors of longer-term outcome.

It is clear that appropriate secondary prevention based on mandated guideline-recommended therapy is important; however, the monitoring of efficacy is even more important. Recording blood pressure, HbA1c and lipid status and modifying therapy during follow-up should result in benefits, even two to three or more years after the STEMI. Things cannot end at the time of discharge. This is a message that needs to be rolled out to primary care physicians, starting with those managing the acute event. Discharge letters and information to patients should emphasise not only the importance of compliance with secondary prevention measures, but also that continued monitoring of their efficacy and appropriate dose modification is really important.

So, back to our analogy. Once your burst tyre has been changed, please check the others and, if there is a “significant” issue with one of them, change it there and then, and maybe not wait till you have left the garage. For the others, check them regularly including pressure (BP), tread wear and tear (HbA1c, lipids) to try to prevent future poor outcomes. For the post-STEMI patient, pro-active monitoring of targets over some years should be obligatory and audited. Longer-term outcomes may thus be improved, as has been alluded to in the SWEDEHEART registry12 and the current EXAMINATION long-term outcome study15.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.