Abstract

Multivessel obstructive coronary artery disease is observed in about half of the STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. Optimal management of non-culprit lesions in these settings continues to be a matter of debate and no consensus has been reached. Lack of robust scientific data led to significant heterogeneity in practice among different centres and countries. In general, three approaches have been defined in haemodynamically stable patients: an aggressive approach with non-culprit PCI during the index procedure, an intermediate approach with non-culprit PCI or CABG as a staged procedure during the index hospital stay or within 30 days, and a conservative approach with non-culprit PCI/CABG only in case of refractory symptoms or objective detection of ischaemia. Based on available data and subsequent post hoc pooled analysis, an intermediate approach has been considered as an accepted option and often adopted. Conversely, the recent PRAMI study results (Preventive Angioplasty in Acute Myocardial Infarction) suggested that an aggressive approach (including non-culprit PCI during the index procedure) provided better clinical outcome than the conservative “culprit only” approach. It is, however, as yet unknown if the aggressive approach used in the PRAMI study is also better than the traditionally advocated intermediate approach with angiographically or FFR-driven staged non-culprit revascularisation. The purpose of this review is to discuss the available evidence and integrate it into daily clinical decision making.

Introduction

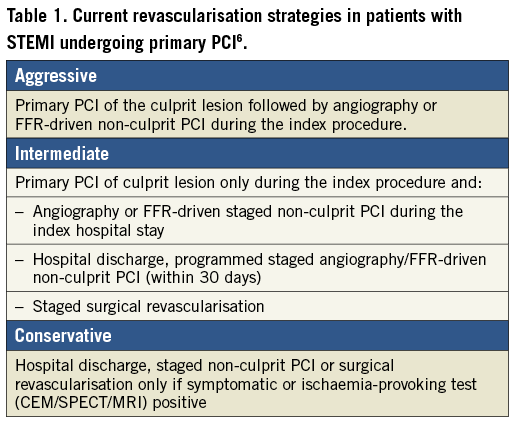

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (p-PCI) is the treatment of choice in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) when it can be performed expeditiously by an experienced team1-3. Except for identification of the culprit lesion, the index angiography provides information about the extent and severity of the non-culprit coronary artery disease. Multivessel obstructive coronary artery disease (MVD) is thereby documented in about half of the patients, and most of these patients are “asymptomatic” before presenting acutely4. Since the presence of MVD substantially increases the risks of major adverse cardiac events, including mortality, the optimal revascularisation strategy has been a matter of debate for many years5-21. Because of the lack of appropriately designed and powered randomised trials, revascularisation strategies for non-culprit stenoses in haemodynamically stable patients without ongoing ischaemia after p-PCI nowadays vary from an aggressive approach with the PCI of all significant non-culprit lesions during the index intervention, to a very conservative approach with hospital discharge and only symptom-driven or ischaemia-driven non-culprit PCI (Table 1). In daily practice, the different strategies are almost equally represented7, which reflects the lack of appropriate scientific data and the numerous advantages/disadvantages of each strategy (Table 2). The aim of this article is to address the pertinent literature critically and apply this knowledge to practical examples.

Scientific evidence

STATE OF THE ART IN 2013

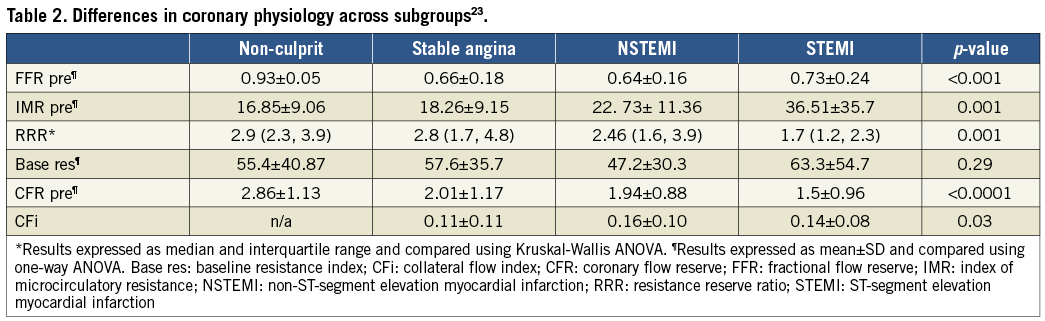

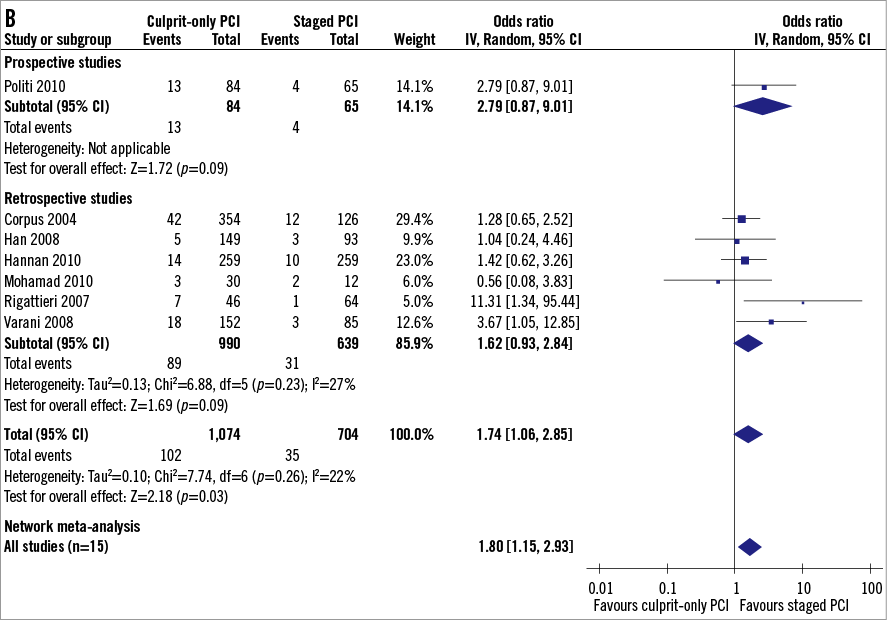

Different “non-culprit lesion” strategies in stable patients with STEMI and MVD undergoing p-PCI have been compared in randomised studies8-10 and non-randomised observational registries11-20, yielding conflicting results. Nevertheless, subsequent pooled analysis combining small randomised trials and observational data suggested that complete percutaneous revascularisation, including angiographically significant non-culprit lesions, may be associated with better prognosis as compared to medical treatment alone. This benefit, however, appeared to be confined to the intermediate strategy when non-culprit PCI was performed during a staged procedure. Indeed, when non-culprit PCI was performed immediately after p-PCI during the index procedure, this resulted in an increased risk of death and cardiovascular events as compared to both staged non-culprit PCI or medical management only. This is also in accordance with a large meta-analysis which included more than 40,000 patients and suggested that non-culprit multivessel PCI during the index p-PCI should be discouraged, and suitable significant non-culprit lesions treated only during the staged procedure, this being associated with lower short- and long-term mortality as compared to index non-culprit multivessel PCI (Figure 1)21. The aggressive approach therefore turned out to be considered the worst option, the intermediate approach the best one, while the conservative approach provided intermediate results21. Indeed, a recent analysis from the HORIZON study has also suggested a deferred angioplasty strategy of non-culprit lesions as the standard approach since multivessel PCI was associated with a greater hazard for mortality and stent thrombosis22. This is also reflected in the latest ESC STEMI guidelines which recommend non-culprit PCI during the index p-PCI only in the setting of cardiogenic shock, despite the fact that there is very little scientific data supporting such a strategy even in this situation3. In stable patients, such an aggressive strategy was clearly discouraged and the following general rules were accepted by the majority of operators:

(i) Single-vessel culprit-only p-PCI should be the default strategy in STEMI.

(ii) Multivessel non-culprit PCI may be justified only in haemodynamically unstable patients.

(iii) Significant non-culprit lesions should be treated medically or by staged revascularisation.

Figure 1. Meta-analysis concerning the optimal management of multivessel disease in STEMI patients and long-term mortality. Comparison between multivessel PCI, staged PCI, and culprit-only PCI. (Reproduced with permission21).

However, evidence so far is derived from angiographic estimation of the non-culprit lesions in the acute setting of STEMI. This is an important limitation due to potential overestimation in the acute phase and overestimation compared to FFR.

HAS PRAMI CHANGED THE GLOBAL STRATEGY?

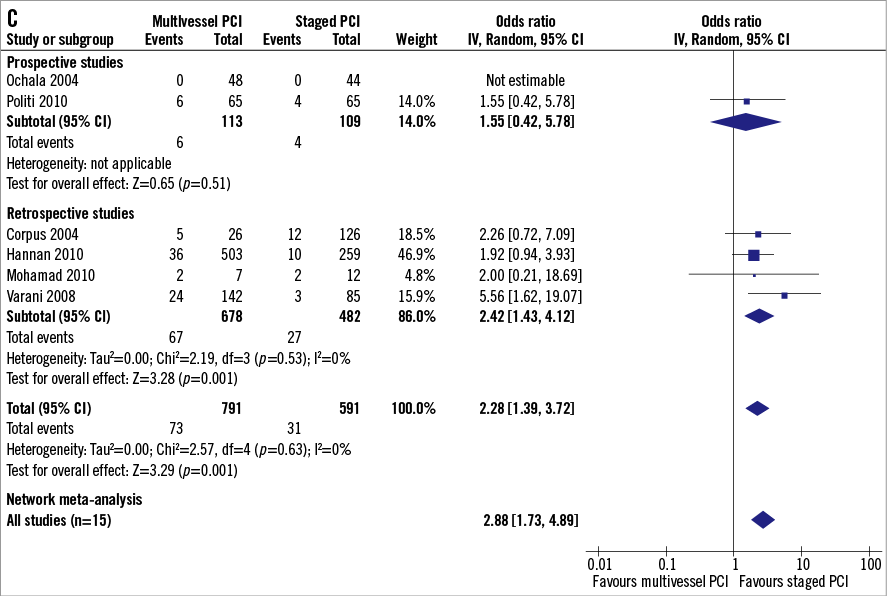

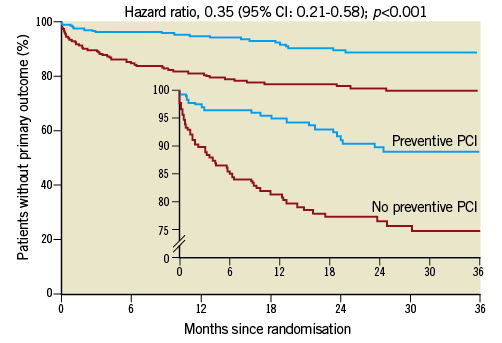

In the recent PRAMI (Preventive Angioplasty in Acute Myocardial Infarction) study, patients with STEMI and MVD were randomised to an aggressive approach designated as “preventive angioplasty” with non-culprit PCI immediately following p-PCI, and a conservative approach with staged non-culprit PCI only in case of refractory symptoms5. In this relatively small study (465 patients), a “preventive angioplasty” strategy was proved to be superior with a significant 65% relative reduction in the combined primary endpoint of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI and refractory angina (Figure 2). Of note, the primary endpoint was mainly driven by a 65% reduction in refractory angina and a 68% reduction in non-fatal MI, although a trend towards a reduction in mortality (p=0.07) was also documented, even if little is known about the clinical relevance of these MI. Despite the significant benefit of “preventive non-culprit angioplasty” demonstrated by this randomised trial, few interventional cardiologists have changed their daily practice.

Figure 2. Benefit of “preventive angioplasty” in the PRAMI study for the primary outcome (cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI and refractory angina). (Reproduced with permission5).

In the first place, the PRAMI study was a small sample size study, underpowered, and the event rate of the control group was high, which might have been driven by the open-label design of the study. However, the most important point is that the PRAMI study essentially provided a comparison between the most aggressive strategy and the most conservative one of non-culprit lesion management. Accordingly, a significant ischaemic burden (>10% of left ventricular) might have been left behind in the conservative arm, and this accounted for increased cardiovascular adverse events. The intermediate approach, with angiographically- or FFR-driven staged non-culprit PCI associated with the best clinical outcome in the previous studies21 and currently still used by the majority of interventionalists, was not tested in the PRAMI study. Nowadays, the real clinical questions about non-culprit lesions are “should we do it?” and “when to do it?”, and those questions remain partially unanswered after the PRAMI study. We believe that the PRAMI study probably suggests that non-culprit lesions could be treated in specific cases according to both patient and anatomy, but does not address the optimal timing for these patients. Of note, the aggressive strategy in the PRAMI study resulted in better results, as demonstrated previously5. Besides narrow inclusion criteria resulting in enrolment of fewer than 50% of screened patients with possible selection bias, this discrepancy can be explained by the evolution of PCI with high penetration of contemporary drug-eluting stents and optimisation of antithrombotic strategy with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors used in more than 75%5,21. However, because of highly selected patients, it is difficult to extrapolate a concept of “preventive angioplasty” to an all-comer STEMI population. Another potential shortcoming is that obstructive MVD was determined only angiographically. It is well known that an acute angiogram during p-PCI may overestimate the severity of non-culprit stenosis23. One fifth of >50% non-culprit lesions during an acute angiogram were <50% during the staged angiogram, which would lead to overtreatment if a “preventive angioplasty” strategy were used. Indeed, no information was provided about non-culprit lesions in the PRAMI study, such as QCA, TIMI flow or lesion characteristics. Moreover, FFR, which can be reliably and safely performed in non-culprit lesions even in the acute phase of STEMI24, was not used in the PRAMI study. As such, the study does not reflect the current state-of-the-art evaluation of the functional importance of the non-culprit lesions, and study addressing the management of MVD in STEMI guided by FFR is urgently needed. Despite the above shortcomings, the PRAMI study undoubtedly opened the door and demonstrated that future randomised controlled studies in this field can be performed safely and will hopefully provide answers to some very pertinent clinical questions. The study also showed that multivessel non-culprit PCI in selected haemodynamically stable patients immediately after successful p-PCI is safe during the index intervention. However, we believe that this study does not support the routine practice of multivessel non-culprit PCI during the index p-PCI procedure as a new gold standard.

ONGOING TRIALS

There are other ongoing studies addressing the issue of MVD management in STEMI patients25. The Complete Versus Lesion-only PRImary PCI Trial (CVLPRIT) (NCT01927549) is assessing the benefit/risk ratio of treating non-culprit lesions. Likewise, the DANish study of optimal acute treatment of patients with ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction 3 (DANAMI-3) trial (NCT01960933) is also testing whether or not to treat non-culprit lesions in patients after successful p-PCI. Integration of FFR in the decision is also tested in the COMPARE ACUTE study (NCT01399736), comparing FFR-guided revascularisation versus conventional strategy in acute STEMI patients with MVD. We believe that these studies will help us to understand better and scientifically identify the best revascularisation strategy for patients with STEMI and concomitant obstructive MVD.

Clinical practice

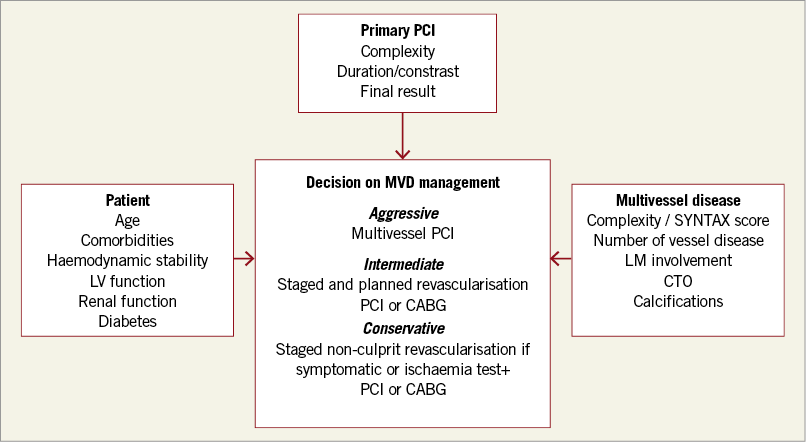

Despite the available evidence and ongoing trials, no study will ever be able to define fully a common strategy for all STEMI patients with MVD. Because these patients are very heterogeneous, any revascularisation strategy should be individualised in this high-risk group of STEMI patients with impaired outcome related to the extent of coronary artery disease. A recent analysis showed that the extent of coronary artery disease (assessed by SYNTAX score) was an independent predictor of mortality in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI26. Needless to say, we should focus first on the best possible p-PCI result on the culprit lesion which brought the patient to the cathlab. A complicated p-PCI with long procedural time, significant contrast load and a suboptimal result, including “slow or no-reflow” and/or distal embolisation, would definitively argue against additional non-culprit PCI in a stable patient during the index procedure. Also, complex angiographic characteristics of non-culprit lesions and predicted PCI complexity would argue for a staged approach. However, rather than staged PCI only, a concept of staged revascularisation including CABG should be considered. In addition to the anatomical complexity of the non-culprit disease and left ventricular/valve function, a complete risk profile, including age and comorbidities, has to be integrated into the decision-making process to select the best revascularisation strategy (Figure 3). Optimal decision making should therefore ideally involve the “Heart Team”, respecting the current revascularisation guidelines for stable coronary artery disease27. Indeed, while most of these STEMI patients with MVD are asymptomatic before the acute event, the non-culprit lesions could be considered part of stable CAD and therefore managed as suggested by the current guidelines based on evidence of symptoms and/or ischaemia27. Indeed, where is the evidence to stent “stable” lesions without proof of complaints and ischaemia? Accordingly, in a patient with complex multivessel disease, impaired left ventricular function and diabetes, surgical revascularisation could be considered despite STEMI as the index event. Last but not least, physiological evaluation of non-culprit lesions using FFR should be encouraged to define the right targets for revascularisation. A complete risk stratification integrating both clinical and angiographic parameters is crucial in STEMI patients with MVD to select the best option for a particular patient ranging from multivessel PCI to a conservative approach. However, in urgent clinical situations such as STEMI, a complete clinical history including expected compliance to drug and planned invasive procedure is often difficult to obtain and, in a doubtful situation, the wise approach could be to postpone additional revascularisation until after discussion with the patient, his family and the referring physician. The cases A, B and C presented in Figure 4-Figure 6 represent the large spectrum of different patients in the same category of “STEMI with multivessel disease”, highlighting that a decision based on the individual patient remains the rule.

Figure 3. Management of multivessel disease in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI.

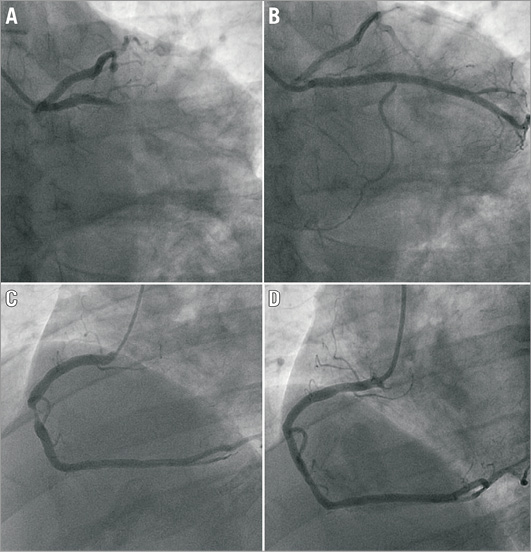

Figure 4. Patient A. In a 46-year-old haemodynamically stable patient with STEMI due to obtuse marginal thrombotic occlusion (A), the culprit lesion was successfully treated with manual thromboaspiration followed by direct stenting (B). In addition to the obvious culprit lesion, subtotal occlusion of the large dominant RCA was found (C). Because of the optimal p-PCI result and critical RCA lesion which was very suitable for PCI, the lesion was directly stented during the index procedure (D), as advocated by the PRAMI study.

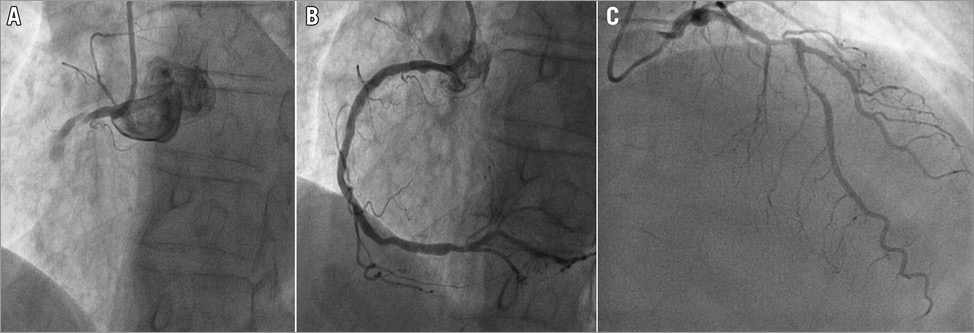

Figure 5. Patient B. In a 78-year-old man with occlusion of a calcified RCA as culprit (A), the lesion was treated by a complex p-PCI requiring AL1 guiding, “buddy-wire” technique and three DES, passed with great difficulty. An acceptable, but suboptimal, final angiographic result with TIMI 2 was obtained and the patient was haemodynamically stable (B). This patient also had a complex stenosis in the mid LAD (C). Because of the suboptimal angiographic result of complex p-PCI associated with significant contrast load and longer duration of the procedure, staged PCI of the non-flow-limiting LAD lesion during the index hospital stay was decided on.

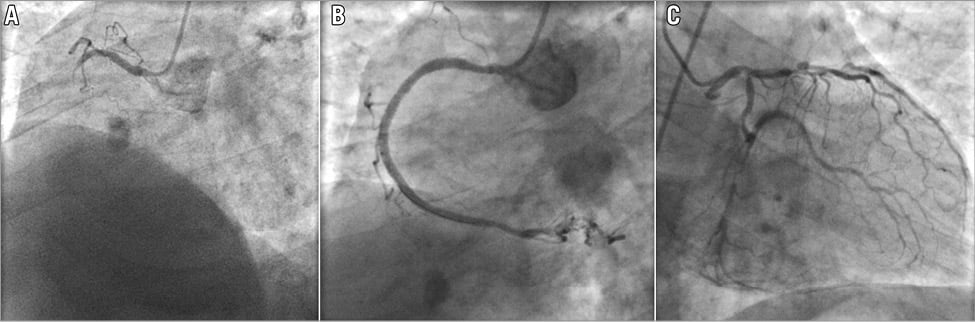

Figure 6. Patient C. This 77-year-old haemodynamically stable patient without previous exertional angina pectoris presented with STEMI due to complete proximal RCA occlusion (A and B). Very diffuse and complex obstructive MVD, including significant distal left main/ostial LCX bifurcation, mid LCX and LAD-large D1 bifurcation lesions, was documented on the left coronary system (C). RCA was successfully treated with p-PCI aborting acute ischaemia (B). The patient was moved to the acute cardiac care unit and his situation was discussed by the “Heart Team” the following morning. The Heart Team advised “off-pump” CABG which was successfully performed four days later and the patient was discharged in good condition seven days later.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.