Although technological developments have dramatically decreased its occurrence, restenosis after coronary stenting remains an important clinical problem even with new-generation drug-eluting stents (DES). Restenosis was once seen as a uniform entity with a single histological substrate: neointimal fibrous hyperplasia, a non-specific histological response to vascular injury observed after coronary interventions. The advent of high-resolution intracoronary imaging with optical coherence tomography (OCT) opened a new dimension in the evaluation of stent restenosis, allowing a detailed assessment of the neointimal tissue and revealing its varied nature1. A whole palette of restenotic tissue patterns became evident, leading to a completely new vision of restenosis as a heterogeneous entity with different causes and features depending on the stent type, time from stent implantation and other factors.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Song et al compare the OCT characteristics of early (<1 year) versus late (>1 year) restenosis occurring in second-generation drug-eluting stents. This retrospective study evaluated all patients who underwent follow-up angiographic and OCT evaluation in two US centres and defined restenosis as an in-stent MLA <3 mm2 by OCT2.

The manuscript provides new insights into the varied nature of the restenotic process and its different morphology depending on the time of occurrence. The authors conclude that heterogeneous restenotic tissue and minimum stent area (MSA) <4 mm2 seem to be more related to early restenosis while the development of neoatherosclerosis is a process more relevant for late restenosis in second-generation DES.

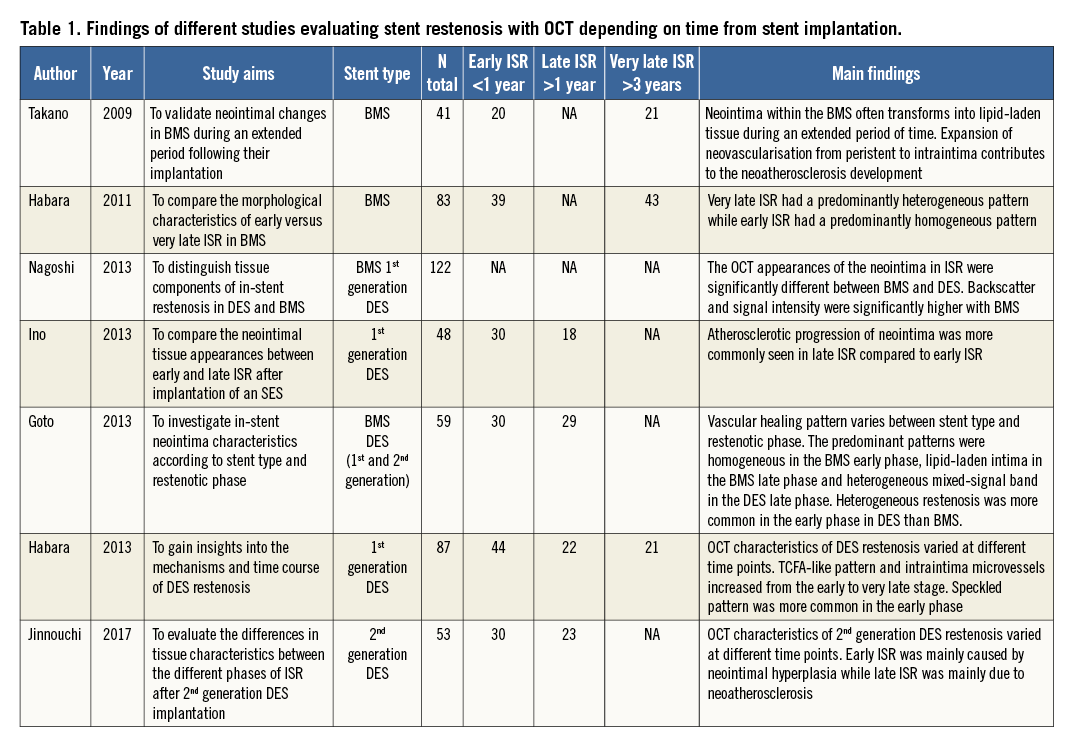

The lack of a common nomenclature with standardised definitions makes the comparison of the multiple studies using OCT in the evaluation of stent restenosis complex (Table 1). Furthermore, marked differences in the OCT structure of the obstructive tissue are frequently found within a single stent, complicating the analysis of the observations.

In the present study, a heterogeneous OCT pattern of in-stent restenosis was more common in early presenters, while some previous studies in bare metal stent (BMS) and first-generation DES more commonly described the heterogeneous pattern in the late phase (Table 1). This difference can be related to the definition of heterogeneous pattern, which is not uniform in the literature, with some studies including certain types of neoatherosclerosis.

Early restenosis was associated with an MSA <4 mm2 in this population. However, the early restenosis group had a smaller vessel size (distal reference lumen area 3.8 vs. 4.7 mm2) and therefore the presence of a higher proportion of stents with a minimum area <4 mm2 is not surprising. A small stent area can be related to either stent underexpansion or stent implantation in a small vessel. Therefore, use of a single stent area value without considering the reference vessel size has serious limitations and does not allow proper detection of stent underexpansion as a cause of restenosis.

The authors found neoatherosclerosis in 24.6% of lesions with a trend towards increased frequency in late presenters, especially intra-stent calcification. The prevalence of neoatherosclerosis in this population is lower than that reported in previous studies of first-generation DES restenosis evaluated with OCT. This could be attributable to DES type; however, recent pathological data have shown no significant difference in the prevalence of neoatherosclerosis between first- and second-generation DES3. The discordances in neoatherosclerosis frequency in the different OCT studies and in comparison with pathology are more probably related to the limitations in the assessment of this entity with OCT. Pathological correlations have shown the potential overestimation in the diagnosis of neoatherosclerosis with OCT, especially regarding thin-cap fibroatheroma detection. Neoatherosclerosis develops earlier in DES than in BMS and its prevalence increases with time from stent implantation, as shown in the present report in agreement with previous OCT studies in first-generation DES. Duration of implant has previously been described as a predictor of neoatherosclerosis together with other factors such as DES use or chronic kidney disease4.

The major limitation of the present paper is the definition used for restenosis (MLA <3 mm2 by OCT). Using a single cut-off point to define restenosis risks overdiagnosis depending on vessel size; stents implanted in small vessels can have an MLA <3 mm2 without restenosis. The angiographic analysis with less than 50% diameter stenosis in both groups demonstrates that the lesions evaluated were not stenotic and emphasises the limitations of this definition.

In summary, the study by Song et al shows that the OCT structure of restenosis in second-generation DES is related to the duration of the implant. These findings are similar to previous studies with first-generation DES and emphasise the new vision of restenosis as a heterogeneous entity with a variety of causes and mechanisms potentially requiring different treatment strategies. In this regard, OCT has offered a new scope in the evaluation of restenosis in vivo, providing a level of detail never before attained. The lack of a common nomenclature and standardisation of the definitions together with the complex correlation between OCT patterns and histological features are challenges for the application of this technology in restenosis evaluation in clinical practice5. However, it offers great potential to identify restenosis causes and guide treatment. Further research is needed to determine whether the different restenotic patterns defined by OCT can respond differently to the treatment options currently available.

Conflict of interest statement

N. Gonzalo is a speaker at educational events with Abbott Vascular. J. Escaned is a consultant and speaker at educational events with Abbott Vascular. N. Ryan has no conflicts of interest to declare.