Abstract

The evidence base evaluating the use of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices in complex, high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention is evolving from a small number of randomised clinical trials to incorporate an amassing body of real-world data. Due to both the growing incidence of the procedures and the limitations of the evidence, there is wide variability in the use of MCS, and the benefits are actively debated. The goal of this review is to perform an integrated analysis of randomised and non-randomised studies which have informed clinical and regulatory decision-making in contemporary clinical practice. In addition, we describe forthcoming studies that have been specifically designed to advance the field and resolve ongoing controversies that remain unanswered for this complex, high-risk patient population.

Due to dramatic improvements in the prevention and treatment of coronary artery disease (CAD), patients increasingly present with an indication for revascularisation later in life, with more anatomically complex disease and more medical comorbidities1. The growth of this population, along with recognition of the cognitive, clinical and procedural approaches to best treat them, helped spawn the field of complex, high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI)23.

Several mechanical circulatory support (MCS) platforms have been developed to support high-risk PCI, though the mortality from these interventions remains high and heterogeneous, ranging from 2% to 20%123. The use of MCS may provide haemodynamic stability and, in turn, promote more complete revascularisation. However, these benefits may be offset by the procedural risks associated with MCS use, including vascular injury and bleeding. Thus, identifying those patients who stand to benefit the most from MCS during PCI remains a critical, yet elusive, goal.

In this review, we will critically appraise the current literature evaluating the benefits and risks of using MCS devices to support high-risk PCI. Given the complexity of this landscape, it is essential to standardise the terminology used to identify and risk-stratify patients undergoing these procedures, understand the comparative efficacy and safety of available MCS platforms, acknowledge the outstanding evidence gaps in the field and suggest how forthcoming studies may address them.

Definition of complex, high-risk PCI

One of the main challenges in studying and performing complex, high-risk PCI is the absence of a universal definition and consensus regarding its treatment. The terms complex and high-risk convey different but complementary information – though they may not necessarily coexist in the same patient. Operators should combine information on patient comorbidities, coronary anatomical characteristics, and the haemodynamic profile at the time of PCI to inform procedural approaches (Central illustration). Multidisciplinary skills are required to integrate data from this triad, which is why a structured Heart Team approach has a Class I recommendation in both European and American guidelines456.

The term “complex” refers to coronary anatomy and lesion characteristics, which usually involve three-vessel disease (3VD), unprotected left main coronary artery or equivalent last patent conduit, saphenous graft lesions, chronic total occlusions (CTO), bifurcation/trifurcation lesions, and calcified or diffuse disease. The coronary anatomy dictates the interventional equipment required to address these complex lesions, from diagnostic tools such as intravascular ultrasound to therapeutic tools such as atherectomy devices or intravascular lithotripsy.

The term “high risk” refers to patient characteristics that can increase the risk of adverse procedural outcomes. Some baseline characteristics can be assessed preprocedurally, such as reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); valvular, vascular, pulmonary, kidney, or liver disease; decompensated heart failure; and potentially the amount of jeopardised myocardium7. There is also a growing need to account for more subjective measures of patient risk, such as clinical frailty, which has been included in risk calculators for conditions like transcatheter aortic valve implantation but not high-risk PCI8910. Similarly, patients who undergo PCI due to prohibitive surgical risk have considerably higher mortality than most other PCI populations, which may be better predicted by surgical risk models11.

In addition to pre-existing comorbidities, the acuity of the clinical presentation at the time of PCI can heavily influence outcomes. This may range from patients presenting for elective PCI in the outpatient setting to patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) of increasing severity (i.e., from non-ST-segment elevation [NSTEMI] to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI]), additionally complicated by decompensated heart failure, cardiogenic shock, or cardiac arrest. Each one of these clinical presentations is reflected in the patient’s periprocedural haemodynamic status, which is another major determinant of clinical outcomes. Together, baseline comorbidities and evolving haemodynamics can synergistically jeopardise the physiological reserve of patients and their ability to tolerate transient ischaemia, bleeding, and hypotension, resulting in them ultimately suffering haemodynamic collapse and adverse events from PCI.

Vasoactive agents are often considered as an initial strategy to increase haemodynamic support and avoid periprocedural hypotension12. Among them, the current consensus is to prioritise agents such as norepinephrine (with α- and β-adrenergic agonism), dobutamine (primarily β-adrenergic), and dopamine (dopaminergic receptor agonism). However, there remains much debate regarding the optimal first-line vasoactive agent to be used when managing haemodynamic collapse from a cardiogenic aetiology, because all vasoactive agents can increase cardiac metabolic demands and promote electrical ectopy, which ultimately limits their desirability for extended use during PCI.

The need to achieve safer and more complete revascularisation in this high-risk population led the scientific community to study the efficacy and safety of using MCS during PCI, with the hypothesis that MCS can reduce myocardial oxygen consumption and improve systemic perfusion and circulatory stability so that interventional cardiologists can perform complete revascularisation with fewer adverse events.

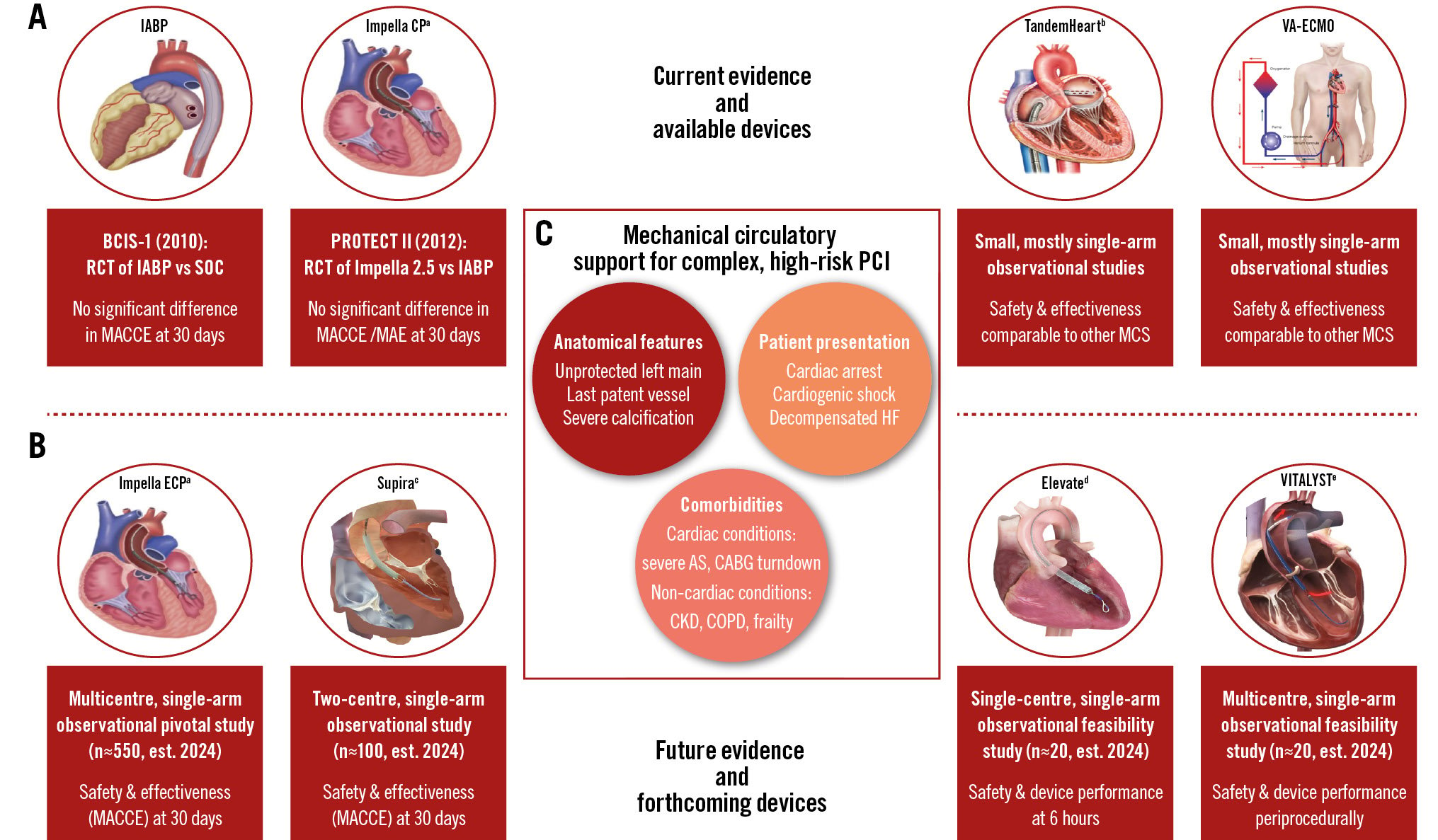

Central illustration. Mechanical circulatory support in complex, high-risk PCI. Currently available devices are displayed in (A), together with the currently available data on their safety and efficacy (red boxes under each device). New devices under development and investigation are displayed in (B), together with ongoing studies that will further inform the field (red boxes under each device). Patient characteristics that may benefit from mechanical circulatory support devices during complex, high-risk coronary interventions are given in (C). aBy Abiomed; bby LivaNova; cby Supira Medical; dby Magenta Medical; eby Boston Scientific. AS: aortic stenosis; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CP: cardiac power; ECP: expandable cardiac power; HF: heart failure; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MAE: major adverse events; MCS: mechanical circulatory support; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SOC: standard of care; VA-ECMO: venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Geographical and temporal variation in MCS use for high-risk PCI

Operators in the USA account for a disproportionate share of MCS use for high-risk PCI. The American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s (NCDR) CathPCI Registry captured over 2 million patients undergoing elective PCI from 2009 to 2018, with MCS use increasing from 0.2% of cases in 2009 to 0.6% in 2018, i.e., a mean annual growth of 0.05%13. While the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was initially the most common MCS device used, the use of other MCS platforms such as transvalvular microaxial flow pumps – herein referred to as Impella (Abiomed) – started to rapidly increase from 2010, eventually representing 70.5% of MCS by 201813. Another US database capturing ~20% of all acute care hospitalisations across federal and private insurers found that MCS use was stable in roughly 3% of all PCI cases from 2004 to 2015, with 90% of MCS volume due to IABP14. Since Impella’s U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2015, however, MCS use increased to 3.5% by 2016 alone – with 32% of MCS volume now due to Impella, but there is a greater than 5-fold variation in the likelihood of Impella use when comparing randomly selected hospitals for statistically comparable patients14.

In contrast, the use of MCS in the United Kingdom has fallen steadily: according to the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) registry, MCS use fell from 2.0% of all adults undergoing PCI in 2010 to 0.9% in 201715. This was driven by a fall in IABP use from 1.9% to 0.8%, without a proportional increase in Impella use (which remained low at around 0.1%)15. Similarly, the Japanese Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Registry evaluated ~250,000 patients undergoing high-risk PCI in 2018, with 0.6% MCS use driven primarily by IABP (85%) over extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO; 6%) and Impella (4%)16. In Italy, however, the multicentre IMP-IT registry enrolled ~400 patients undergoing high-risk PCI across 17 centres from 2004 to 2018, of which 44% received MCS, with an increasing rate of 40% per year17.

In summary, there is significant variation among different high-income countries in the use of MCS for high-risk PCI, with a significant increase in the use of Impella concentrated in the USA in recent years.

Current evidence for MCS platforms to support high-risk PCI

To date, the most rigorous body of evidence on the safety and effectiveness of MCS platforms in high-risk PCI is limited to one randomised controlled trial (RCT) for IABP versus medical therapy and one RCT for Impella versus IABP – neither of which met its primary endpoint (Table 1). Clinicians should also be aware of the limited non-randomised evidence available for other MCS platforms that are currently used in high-risk PCI23 (Figure 1).

Table 1. Overview of key clinical trials for MCS use in high-risk PCI.

| Trial information | BCIS-1 United Kingdom, 2005-2009 |

PROTECT II US, 2007-2010 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study overview | Experimental arm: IABP Control arm: standard of care |

Experimental arm: Impella 2.5a Control arm: IABP |

||

| Study type | Randomised controlled trial (1:1) Prospective, multicentre, open-label |

Randomised controlled trial (1:1) Prospective, multicentre, open-label |

||

| Inclusion criteria | LVEF ≤30% and BCIS-1 jeopardy score ≥8, or Unprotected LMCA disease, or Last patent coronary conduit |

LVEF ≤35% and Unprotected LMCA disease, or Last patent coronary conduit, or LVEF ≤30% and 3VD |

||

| Exclusion criteria | Cardiogenic shock AMI within the previous 48 hours Contraindications to IABP use |

Cardiogenic shock STEMI within the previous 24 hours Contraindications to IABP or Impella use |

||

| Primary endpoint | Time horizon: 28 days, ITT; | Time horizon: 30 days, ITT; | ||

| Composite MACCE, including death, AMI, stroke, repeat revascularisation | Composite MAE, including death, AMI, stroke, repeat revascularisation, need for cardiac or vascular operation, acute kidney injury, intraprocedural hypotension, cardiac arrest, aortic insufficiency | |||

| Study results | IABP (n=151) | SOC (n=150) | Impella (n=216) | IABP (n=211) |

| Crossover | 0 | 18 (12%) --> IABP | Not allowed | Not allowed |

| Event rates | 15.2% | 16.0% | 35.1% | 40.1% |

| OR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.51-1.76; p=0.85 | p=0.227 | |||

| aBy Abiomed. 3VD: three-vessel disease; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CI: confidence interval; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; ITT: intention-to-treat; LMCA: left main coronary artery; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MAE: major adverse events; MCS: mechanical circulatory support; OR: odds ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SOC: standard of care; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | ||||

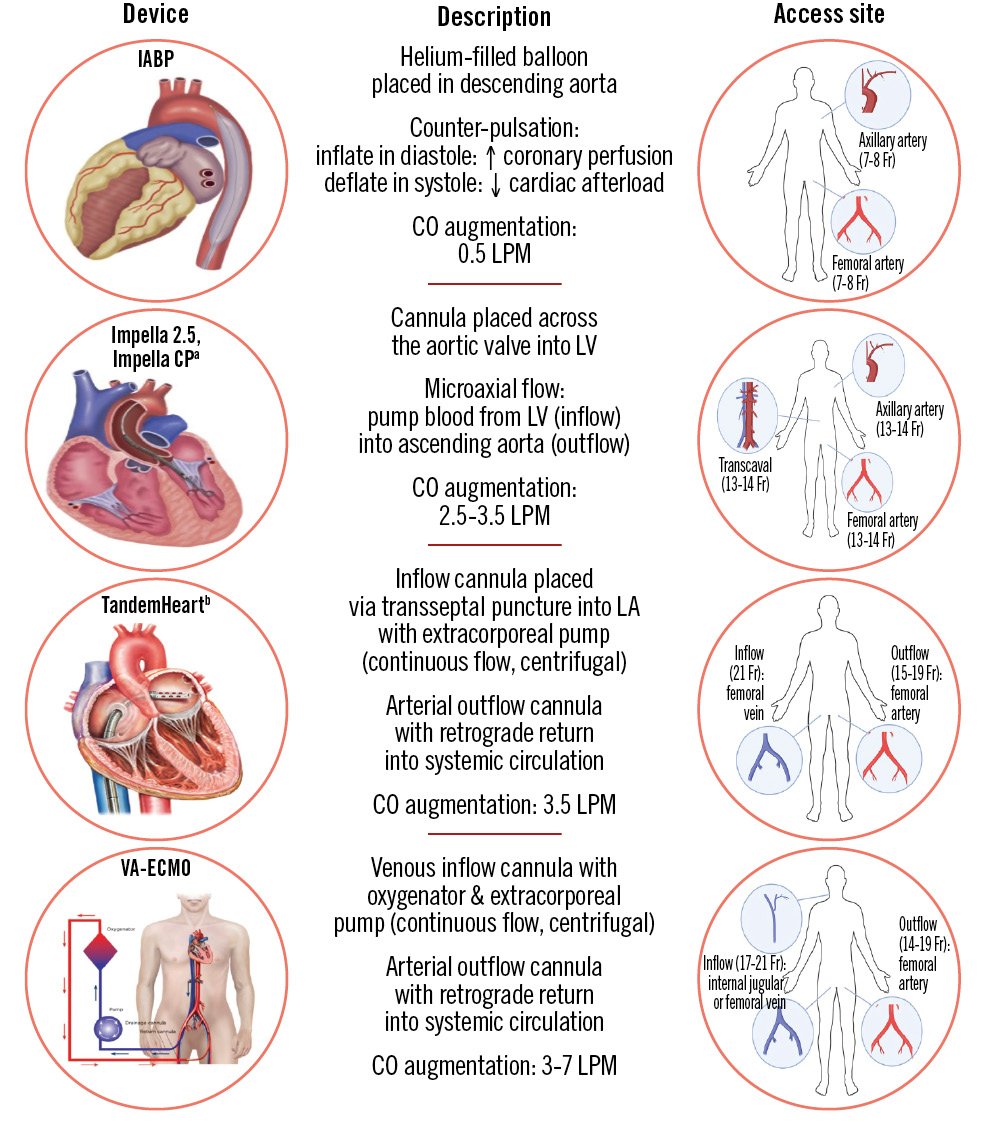

Figure 1. Comparative characteristics of currently available MCS platforms for haemodynamic support during PCI, ordered by increasing capacity of circulatory support. aBy Abiomed; bby LivaNova. CO: cardiac output; CP: cardiac power; Fr: French; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; LA: left atrium; LPM: litres per minute; LV: left ventricle; VA-ECMO: venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Intra-aortic balloon pump

The evidence on IABP use in high-risk PCI was observational until 2010, when the BCIS-1 trial found no significant reduction in major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at 28 days in the IABP group compared to control (15.2% vs 16.0%, odds ratio [OR] 0.94, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.51-1.76)18. Patients in both arms underwent similar amounts of revascularisation, with IABP patients suffering fewer periprocedural events like hypotension but significantly higher rates of access site complications and bleeding (Table 1). After a median follow-up of 4.2 years in the United Kingdom’s nationwide census, IABP patients were found to have significantly lower all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44-0.98) – though the lack of information on cause of death limited a mechanistic explanation to assign beneficial effects to the IABP19. Despite this limited randomised evidence, the IABP began to be used as the control arm for subsequent studies of MCS platforms, as described below.

Transvalvular microaxial flow pumps – Impella

Published in 2012, the pivotal PROTECT II trial was the first head-to-head comparison of two MCS devices in elective high-risk PCI: Impella and IABP2021. The study was stopped early for futility after an interim analysis showed no significant difference in the composite outcome of 30-day major adverse events (MAE) between Impella and IABP (35.1% vs 40.1%; p=0.23). Furthermore, while the trial protocol recommended complete revascularisation for all procedures, patients in the Impella arm received significantly more runs and longer durations of rotational atherectomy, which may have further compromised randomisation (Table 1).

Even though PROTECT II did not meet its primary endpoint, subsequent prespecified and post hoc analyses demonstrated a significant reduction in MAE at 90 days in the per-protocol population (Impella 40.0% vs IABP 51.0%; p=0.02), suggesting that perhaps the original 30-day window may have been too short to observe the benefits of the more extensive revascularisation allowed by Impella2122. In addition, the sponsor offered real-world data (RWD) from the retrospective USpella Registry to demonstrate that the rates of the safety and effectiveness endpoints observed in contemporary clinical practice were comparable to those observed in PROTECT II23. Starting in 2016, additional iterations of the Impella device began to enter the market, namely Impella CP, but also Impella 5.0 and LD (which typically require surgical cutdown for insertion), with progressively increasing maximum average flow (Figure 1).

Though not directly applicable to elective PCI, the recently published DanGer-Shock trial assessed the efficacy of the Impella CP in 360 patients with STEMI-related cardiogenic shock. Results showed a significant reduction in 6-month all-cause mortality in the Impella group compared to standard of care (45.8% vs 58.8%, HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.55-0.99; p=0.04) despite a significantly higher risk of bleeding, limb ischaemia, and need for renal replacement in the Impella arm24. This net reduction in mortality is the first piece of randomised evidence to show a meaningful benefit of the Impella device in the setting of cardiogenic shock. More broadly, this trial highlights the importance of implementing standardised algorithms for implantation, escalation or weaning of MCS – for example, by mandating 48 hours of uninterrupted MCS before attempting any weaning. Many of these valuable lessons can now be translated to upcoming trials of MCS use in high-risk PCI.

Left atrial to femoral artery bypass system – TandemHeart

The data for TandemHeart (LivaNova) in high-risk PCI consist of small, single-arm case series, with comparable outcomes to other MCS devices25. In a meta-analysis comparing 1,345 patients undergoing high-risk PCI with Impella 2.5 versus 205 patients with TandemHeart support, there were comparable periprocedural outcomes, with higher rates of short-term mortality with TandemHeart versus Impella (8% vs 3.5%) but lower rates of major bleeding (3.6% vs 7.1%)26.

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

The data for venoarterial (VA)-ECMO in high-risk PCI consist of single-arm observational studies, with periprocedural complications and outcomes comparable to other MCS devices27282930 and prophylactic VA-ECMO use associated with lower in-hospital (13.5% vs 77.8%) and 1-year mortality (21.2% vs 77.8%) compared to rescue VA-ECMO. One small study (n=41) compared outcomes between VA-ECMO and Impella CP for high-risk PCI, with no differences in periprocedural haemodynamic instability, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), or bleeding but higher mortality with VA-ECMO (14.3% vs 7.4% with Impella)31.

Real-world evidence on MCS use for high-risk PCI in contemporary clinical practice

Given the limited available data from RCTs of MCS in high-risk PCI, the scientific community has tried to leverage clinical registries and insurance claims databases to generate observational evidence in both Europe and the US. Results from the multicentre cVAD registry (formerly known as USpella Registry) seem to support the pathophysiological role of MCS in preventing profound periprocedural hypotension, as demonstrated by lower-than-expected rates of acute kidney injury at 48 hours post-PCI in a cohort of 314 patients and improvements in LVEF at 30 days in a cohort of 689 patients3233. Thus, it is possible that the benefit of MCS in high-risk PCI may be enhanced with a preventive rather than a reactive approach, in order to minimise periprocedural hypotension. This hypothesis seems to align with results from retrospective observational studies in both Europe and the US, where prophylactic Impella support was associated with significant reductions of both in-hospital and 1-year mortality. These findings motivated the development of the dedicated PROTECT-EU Registry, which will prospectively evaluate 90-day outcomes after high-risk PCI with preventive Impella use343536.

Some observational studies also performed comparative effectiveness analyses of Impella versus IABP support. The US NCDR’s CathPCI Registry leveraged a population of 6,905 patients undergoing high-risk PCI with either Impella or IABP use between 2009 and 2018; analyses using a propensity score model with inverse probability of treatment weighting found a significantly higher rate of in-hospital MACE associated with IABP use, compared to Impella – although Impella patients had more periprocedural complications. Notably, this nationwide clinical registry is able to capture detailed clinical and angiographic features that are usually unavailable in claims databases and which were thereby integrated in the propensity score model13. Similar findings were replicated in a larger claims-based cohort capturing ~20% of all acute care hospitalisations across federal and private insurers in the US, which leveraged 48,179 patients undergoing non-emergent PCI with MCS from 2016 to 201937. This study performed propensity adjustment to balance clinical characteristics between patients treated with Impella CP and IABP; it found that Impella use was associated with significantly lower rates of in-hospital mortality, myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiogenic shock compared to the IABP, with similar rates of bleeding and stroke.

While most observational analyses primarily focus on short-term outcomes, the recent PROTECT III registry provides information on long-term outcomes in contemporary clinical practice. PROTECT III was a single-arm, prospective, multicentre, FDA-audited post-approval study of Impella devices in the US38. This study followed 1,134 patients from 2017 to 2020; among them, 504 patients would have met eligibility conditions for the PROTECT II trial, and their outcomes were compared against PROTECT II patients (used as a historical control). Compared to PROTECT II, the PROTECT III patients were found to undergo PCI of more and higher-risk vessels, with longer and more calcified lesions, with correspondingly higher use of rotational atherectomy and ultimately achieving greater complete revascularisation. At 90 days of follow-up, PROTECT III patients had significantly lower rates of adjusted MACCE, compared to PROTECT II patients (15.1% vs 21.9%; p=0.04), and decreased in-hospital bleeding (1.8% vs 9.3%; p<0.001), further supporting the idea that high-risk PCI with Impella support is becoming an increasingly safe and effective way to promote complete revascularisation, which in turn may improve long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

Limitations of observational data for MCS use in high-risk PCI

The conflicting results of observational real-world studies highlight how the available RWD are unable to comprehensively capture all patient, operator, hospital, and procedural characteristics that may influence the decision or the ability to offer MCS to a heterogeneous range of PCI patients. These unmeasured variables inevitably threaten RWD with problems like treatment selection bias, as patients who receive MCS are likely to be fundamentally different from patients who do not, and those who receive prophylactic MCS are also likely to be very different from those receiving MCS as bailout.

A recent study, carried out in collaboration with the FDA, employed a series of methods to compare 30-day mortality and readmissions between IABP, Impella and unsupported PCI for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (AMI-CS), leveraging a population of 23,478 US Medicare patients treated between 2015 and 201939. While the AMI-CS population is not interchangeable with the complex, high-risk PCI population, this study elucidated how observational comparisons of MCS devices using real-world data may be intractably challenged by violations of statistical assumptions, challenging the causal interpretability of their findings. The authors concluded that more detailed PCI registries could help overcome some limitations of the presently available RWD, but, given the increasingly more controversial role of Impella-supported PCI, randomised data are urgently needed to inform clinical care.

Limitations of current MCS devices and novel MCS solutions

One of the key challenges of current MCS devices is the requirement for large-bore femoral access, which poses risks of vascular injury, limb ischaemia and major bleeding, further exacerbated by the mandatory use of therapeutic anticoagulation for indwelling MCS devices. Some risks may be mitigated by preprocedural imaging to assess for peripheral vessel anatomy, calibre, atherosclerosis, calcifications or prior surgical/endovascular interventions40. Vascular closure devices (VCD) are also used to reduce postprocedural bleeding risks after large-bore arterial access. These include suture-based systems, collagen plugs, and polyethylene glycol-plugs and clip-based systems41. One potential advantage of suture-based systems (like the Perclose ProGlide [Abbott]) is that sutures can be delivered before insertion of large-bore sheaths and be tightened post-procedure – although their sterility is challenged when prolonged MCS is needed post-procedure. Post-closure techniques thus remain crucial to reduce bleeding complications and may sometimes require either two suture-based systems (at opposite orientations relative to the long axis of the arteriotomy) or hybrid methods that combine suture- and plug-based techniques424344. Newer VCD systems, such as the plug-based MANTA device (Teleflex), offer post-closure haemostasis for sheaths up to 23 Fr45. In extreme cases, a crossover balloon can be placed via contralateral access to occlude the iliac artery during MCS device extraction41.

These frequent challenges with femoral access also pushed the field to develop alternative access strategies (Table 2)46. Among those, transaxillary access is gaining popularity due to benefits like early patient mobility. Preprocedural imaging and ultrasound-guided access can prevent damage to nearby structures (brachial plexus and lungs), and manual pressure (plus suture-mediated devices as needed) can reduce bleeding after closure, with high success and low complication rates shown in multicentre registries4647. Alternatively, transcaval access can bypass the iliofemoral arteries by creating a channel between the inferior vena cava (IVC) and abdominal aorta46. This procedure usually requires preprocedural imaging to identify optimal aortic crossing points for electrified wires to connect the IVC and aorta, and for balloon aortic predilation and telescoping catheters to cross without wire buckling and potential lacerations (which would require balloon tamponade or covered stents). Caval-aortic fistulas, which typically close over time, can be mitigated with nitinol occluder devices or investigational aortic transcaval closure devices4648. Lastly, the Single-access for Hi-risk PCI (SHiP) technique allows operators to perform PCI with MCS and a single arterial access point. To do so, the haemostasis valve of the 14 Fr Impella sheath can be pierced with a micropuncture needle, which allows intravascular placement of an 8 Fr sheath for concurrent PCI. Notably, after the PCI sheath is removed, the defect in the haemostasis valve usually seals automatically49.

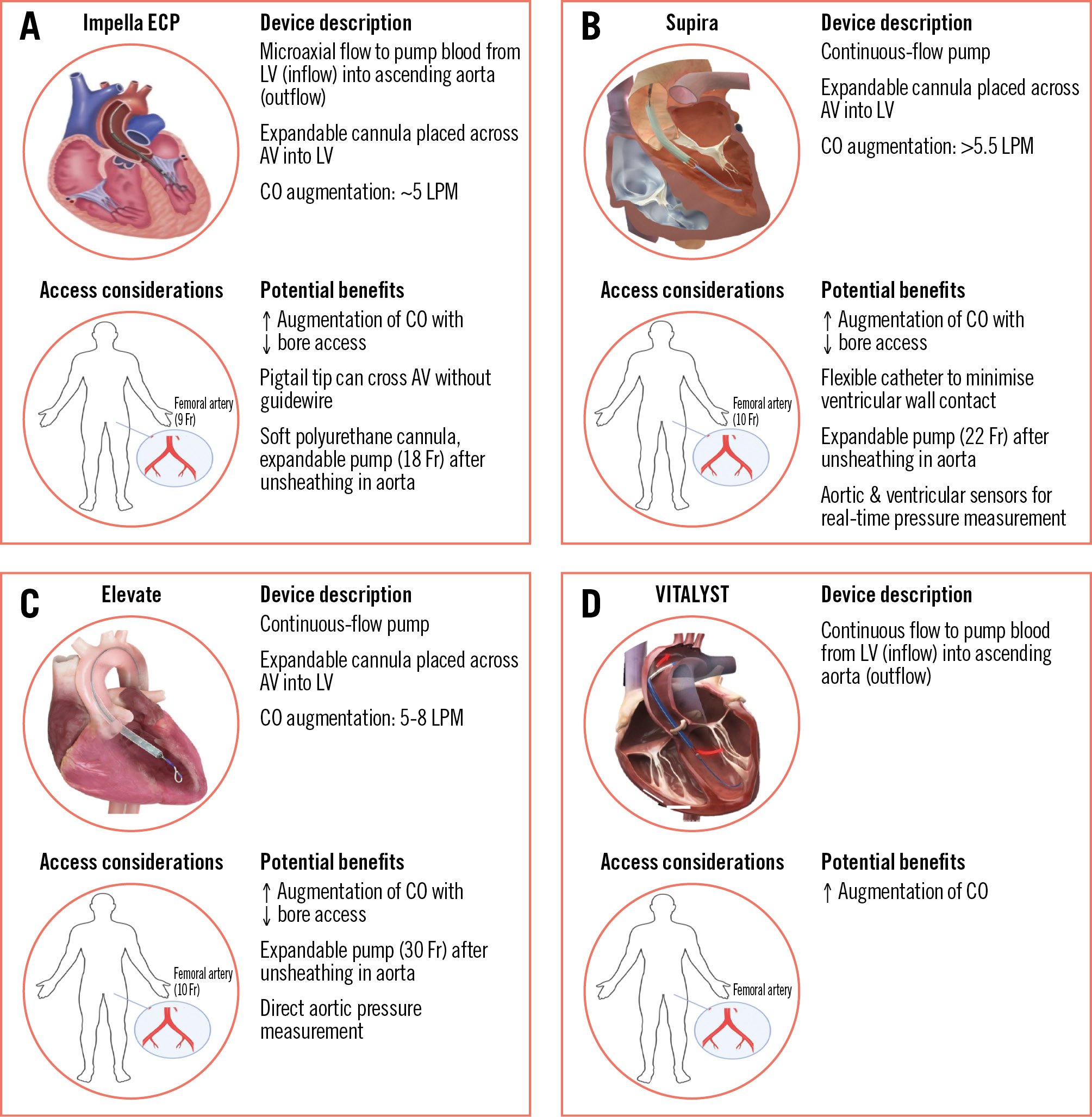

Some of the aforementioned limitations and risks of MCS devices may be overcome with the introduction of a new generation of MCS platforms (Figure 2). Among the key shared characteristics, these novel devices have an expandable pump design that can be initially compressed into lower-profile sheaths (9-10 Fr) in order to reduce access site bleeding but can then expand once the pump is unsheathed in the aorta and provide higher haemodynamic support (5-7 L/min) compared to traditional non-expandable pumps. Furthermore, the use of softer and more flexible cannulas may minimise ventricular wall irritability and arrythmias. Other requirements, such as the need for anticoagulation with indwelling devices, will likely remain unchanged.

Of the novel MCS platforms, the Impella ECP device is furthest along in development; in December 2022, the pivotal trial enrolled its first patient for high-risk PCI (Table 3)50. The Impella ECP device has a significantly smaller profile upon insertion and removal from the body (9 Fr) but can expand to 18 Fr once in position to deliver a flow of 3.5-5 L/min; furthermore, it can cross the aortic valve without a guidewire, and its cannula can collapse whenever the pump is inactive to allow the aortic valve leaflet to naturally close around the device51. The Elevate (Magenta Medical) and Supira (Supira Medical) systems also have ongoing early-stage clinical trials with promising results5253. They similarly offer greater cardiac output augmentation with smaller-bore femoral access (10 Fr) compared to existing devices due to their ability to expand to 30 Fr and 22 Fr, respectively, after unsheathing in the aorta. The Supira system also offers aortic and ventricular sensors, which allow for real-time direct pressure measurements52. Lastly, the VITALYST platform (Boston Scientific) recently completed its first-in-human study, though no data are yet available on its safety or effectiveness profile54.

Table 2. Alternative access sites for MCS platforms.

| Access type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Preprocedural imaging | Sheath requirement | Closure technique | Specialised equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transaxillary | Early patient mobility with indwelling device; Manual haemostasis possible; Obstructive atherosclerosis rare |

Smaller vessel calibre compared to CFA; Technical challenges due to anatomical position; Increased stroke risk |

CTA, ultrasound or procedural angiography to characterise vessel anatomy, calibre and atherosclerosis | Sheath size limited by smaller vessel calibre | Suture-mediated closure device; Manualhaemostasispossible | None |

| Transcaval | Rare access site bleeding; No risk ofischaemic limb; Favourable operator ergonomics compared toaxillary access |

Risk of retroperitoneal bleeding, with nomanual haemostasisoptions; Risk of high-outputfistula (between aortaand IVC); Bed rest requirement with indwellings heath |

CTA of abdomen/pelvis to identify ideal crossing site from IVC to aorta | None | Nitinol occluder device for transcaval closure | Electrifying wire, specialised catheters, compliant balloons for transcaval crossing |

| SHiP | Reduced need for multiple arterial access sites | None | None | 14 Fr Impella sheath in CFA | None | |

| Advantages and disadvantages of alternative access sites (compared to traditional femoral arterial access), with respective technical considerations. CFA: common femoral artery; CTA: computed tomography angiography; IVC: inferior vena cava; MCS: mechanical circulatory support; SHiP: Single-access for Hi-risk percutaneous coronary intervention | ||||||

Figure 2. Characteristics and potential benefits of new MCS devices in development. New generation of approved and/or experimental platforms for haemodynamic support during PCI, ordered by increasing capacity of circulatory support based on expandable pump design. A) Impella ECP (Abiomed); (B) Supira (Supira Medical); (C) Elevate (Magenta Medical); (D) VITALYST (Boston Scientific). AV: aortic valve; CO: cardiac output; Fr: French; LPM: litres per minute; LV: left ventricle; MCS: mechanical circulatory support

Table 3. Forthcoming evidence for new MCS devices in high-risk PCI.

| Trial information | Impella ECPa: pivotal study & continued access protocol | Supira systemb: feasibility study of the Supira system for HR-PCI | Elevate system: ELEVATE Ic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | Single arm Prospective, multicentre Estimated n=556 |

Single arm Prospective, two-centre Estimated n=100 |

Single arm Prospective, single-centre Estimated n=20 |

| Inclusion criteria |

Age 18-90 years old; |

Age 18-90 years old; Elective or urgent high-risk PCI; Haemodynamically stable |

Age 40-83 years old; Elective or urgent high-risk PCI;EF ≤45% and Unprotected LM Unprotected last patent coronary conduct 3VD |

| Exclusion criteria | Cardiogenic shock or acute decompensated heart failure; Prior stroke with neurological deficits; Contraindications to investigational device | STEMI within 30 days; Prior stroke with neurological deficits; Mechanical ventilation for primaryrespiratory dysfunction; Contraindications to investigational device | Cardiogenic shock; Prior stroke with neurological deficits; Contraindications to investigational device |

| Primary endpoint | The 30-day rate of MACCE Device-related major vascular complications Device-related major bleeding |

The 30-day rate of MACCE Periprocedural (6 hours) rate of Device performance Device-related major adverse events |

Periprocedural (6 hours) rate of Device performance (including hypotension) Device-related major adverse events |

| Estimated completion | October 2024 | December 2024 | March 2024 |

| aBy Abiomed; bby Supira Medical; cby Magenta Medical. 3VD: three-vessel disease; ECP: expandable cardiac power; EF: ejection fraction;HR-PCI: high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention; LM: left main; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MCS: mechanical circulatory support; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | |||

The future of high-risk PCI trials with MCS support: what to expect next

In April 2021, the first patient was enrolled in the PROTECT IV trial, a US-based, multicentre, prospective, open-label RCT that aims to recruit 1,252 patients to compare Impella-supported PCI with standard-of-care PCI55. In August 2021, the first patient was also enrolled in CHIP-BCIS3, a United Kingdom-based, multicentre, prospective, open-label RCT that aims to recruit 250 patients to compare MCS to standard-of-care PCI56. The results of these forthcoming RCTs are highly awaited in 2026, as some key changes in their design (compared to PROTECT II) could help identify which patients may benefit from elective percutaneous MCS (pMCS) use – though some key questions may remain unanswered (Table 4).

In terms of study design, the new trials acknowledge the lack of definitive evidence to support elective use of any pMCS and, thus, leave IABP use to the operator’s discretion (PROTECT IV) or limited to bailout only (CHIP-BCIS3) in the control arm. On the other hand, these trials also acknowledge increasing evidence supporting complete revascularisation in ACS patients and, thus, have expanded inclusion criteria for both NSTEMI and STEMI patients, as these high-risk subgroups could derive significant benefit from elective pMCS use5758. On a similar note, they depart from PROTECT II by acknowledging that not all 3VD presentations have similar risk, and they prespecify patient subgroups with high-risk, complex coronary anatomy (i.e., proximal, bifurcation, calcified or CTO lesions) that could particularly benefit from elective MCS use. In terms of efficacy evaluation, the new trials build on an important lesson learned from PROTECT II, namely that a 30-day time window may be too short to uncover the benefit of revascularisation with MCS. As such, they have extended the time horizon to 1 year (CHIP-BCIS3) or even 3 years (PROTECT IV) and added the reduction of cardiovascular hospitalisations to the primary endpoint (Table 4).

Despite these significant improvements in study design, it is possible that the safety evaluation of pMCS platforms may remain relatively understudied in these new trials – because key safety events like bleeding or access site complications have not been formally included in primary endpoints and because novel MCS platforms with lower-profile pumps and sheaths (such as Impella ECP, see above) have entered the market after the launch of these trials. Last but not least, another key lesson learned from PROTECT II was that the use of Impella was associated with a disproportional use of rotational atherectomy in the experimental arm. However, publicly available protocols from PROTECT IV and CHIP-BCIS3 do not seem to specify how they will ensure that treatment protocols remain standardised and balanced between experimental and control arms – if history repeats itself, randomisation and trial results may be once again compromised (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of prior and forthcoming RCTs of MCS use in high-risk PCI.

| Limitations of prior RCTs in high-risk PCI with MCS | How forthcoming RCTs may advance the field | Questions that may remain unanswered |

|---|---|---|

| Study design considerations | ||

| PROTECT II: mandatory use of IABP in control arm (despite limited evidence) | PROTECT IV: IABP use in control arm is left to operator discretion; CHIP-BCIS3: IABP or ECMO use is allowed only as bailout |

- |

| PROTECT II: coupling of EF and coronary anatomy in same inclusion criteria;Limited granularity in defining complex coronary disease | PROTECT IV/CHIP-BCIS3: Uncoupling of EF and coronary anatomy as independent inclusion criteria; Specific inclusion of high-risk subgroups of complex coronary disease (i.e., proximal, bifurcation, calcified or CTO lesions) |

- |

| PROTECT II: exclusion of patients with recent AMI | PROTECT IV: inclusion of patients with recent NSTEMI and STEMI | - |

| Efficacy and safety considerations | ||

| PROTECT II: 10-point MAE primary endpoint with combined efficacy and safety events; PROTECT II: 30-day time horizon for primary endpoint was too short to uncover MCS benefit |

PROTECT IV/CHIP-BCIS3: Primary endpoint simplified to death, MI, stroke, revascularisation or CV hospitalisations; PROTECT IV: primary endpoint extended to 3 years of follow-up; CHIP-BCIS3: primary endpoint extended to 1 year of follow-up |

PROTECT IV/CHIP-BCIS3: troponin cutoffs to define periprocedural MI are not specified, and these can significantly affect event rates |

| PROTECT II: significantly higher use of rotational atherectomy in experimental arm | - | PROTECT IV/CHIP-BCIS3: unclear how treatment will be standardised between experimental and control arms |

| PROTECT II: limited device safety assessment (i.e., major bleeding) | PROTECT IV: mandatory preprocedural vessel imaging to mitigate device-related safety events | PROTECT IV: major bleeding and vascular complications are not included in primary endpoint; CHIP-BCIS3: MCS device characteristics are not prespecified for experimental arm; Safety data may not be reflective of contemporary devices that recently entered the market |

| AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CTO: chronic total occlusion; CV: cardiovascular; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EF: ejection fraction; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; MAE: major adverse events; MCS: mechanical circulatory support; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; RCT: randomised controlled trial; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | ||

Conclusions

Continuous improvements in medical and interventional therapies now allow patients to survive coronary syndromes and transition to an older and medically and anatomically complex population with progressive ischaemic cardiomyopathy – for which clinical evidence increasingly supports complete revascularisation. This clinical need, in turn, has catalysed the development of innovative devices for mechanical circulatory support, even though their progressive adoption in medical practice so far has been propelled more by clinical intuition rather than definitive evidence.

To date, only two randomised trials have been completed among patients undergoing complex, high-risk PCI with MCS, both with inconclusive and controversial results. A growing body of real-world data has been generated, but even the most rigorous analytical methods seem insufficient to definitively prove the effectiveness and safety of these powerful, yet risky, (and often expensive) devices. Nonetheless, physicians today are faced with the immediate task of deciding if and when to offer pre-emptive MCS to their patients undergoing high-risk PCI. Understandably, they may find this large amount of conflicting evidence more daunting than helpful to drive decision-making at the present time.

While awaiting the results of forthcoming randomised trials, the current expert consensus suggests considering MCS when there is strong clinical concern for haemodynamic compromise during PCI, and several algorithms have been proposed to predict the need for MCS by incorporating both patient substrate and procedural requirements based on coronary anatomy4059606162. These recommendations notwithstanding, we also acknowledge a high degree of variability within the currently available algorithms. Operators may reasonably choose to assign different weights to each proposed risk factor, based on both the severity of their individual manifestations and their combination with one or more additional risk factors. Since there may often be significant haemodynamic equipoise on arrival at the catheterisation laboratory, we also agree with the recommendation of pulmonary artery catheter evaluation as a helpful tool to identify patients with elevated cardiac filling pressures and poor haemodynamics (who may benefit the most from upfront circulatory support), as well as monitoring patients who may not initially qualify and may dynamically evolve during the course of the PCI procedure.

As we prepare for the next wave of randomised controlled trials in high-risk PCI, clinicians should become familiar with the evidence available to date but also with the limitations and the lessons learned along the way – most importantly, understanding that bias may ultimately influence both observational and randomised studies. A deep understanding of analytical methods and nuanced clinical decision-making are needed as the scientific community continues to collaborate and put its best foot forward to find an answer that can improve outcomes for their patients.

Conflict of interest statement

D.J. Abbott has received consulting fees from Abbott, Medtronic, Penumbra, and RapidAI; and research funding from Boston Scientific, MedAlliance, MicroPort, and Recor Medical. R.W. Yeh has received research funding and consulting fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic; and research funding from Bard, Cook, and Philips. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this work to declare.