Abstract

Aims: In the HORIZONS-AMI trial, bivalirudin compared to unfractionated heparin (UFH) plus a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI) improved net clinical outcomes in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at the cost of an increased rate of acute stent thrombosis. We sought to examine whether these effects are dependent on time to treatment.

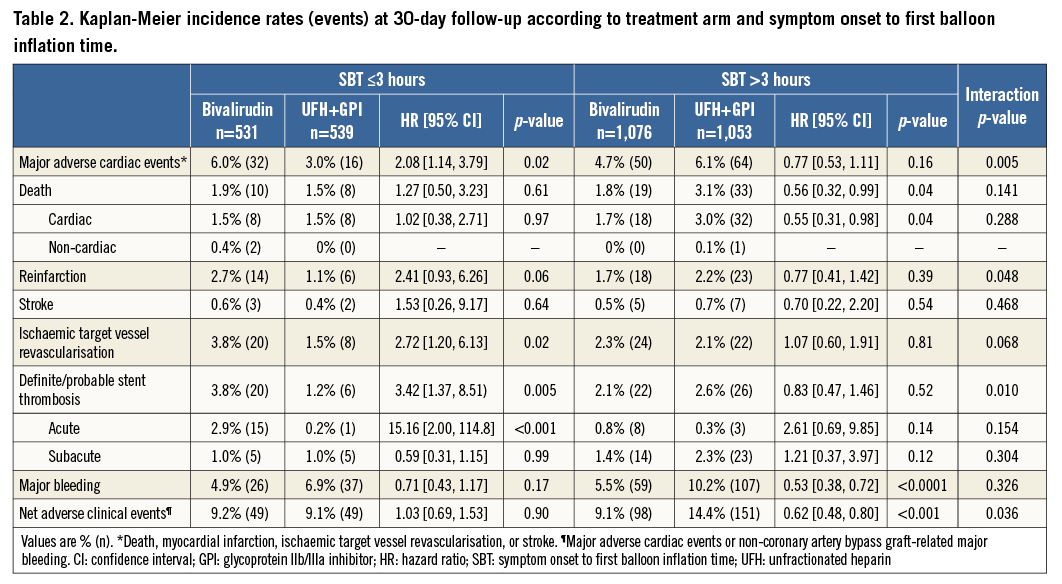

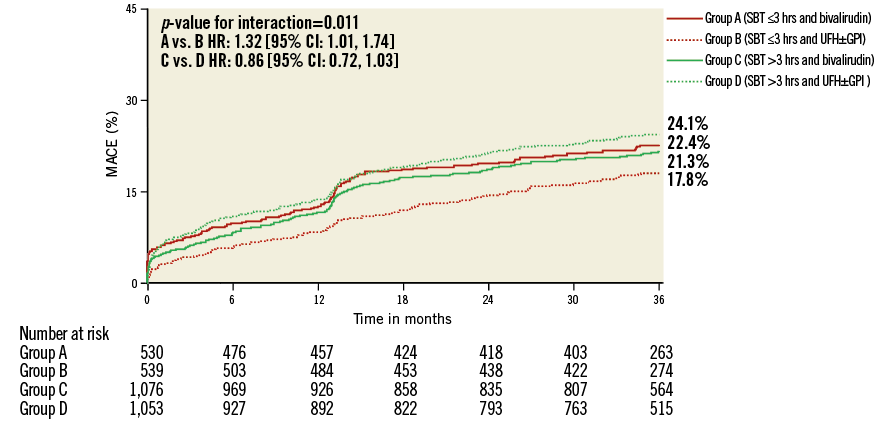

Methods and results: The interaction between anticoagulation regimen and symptom onset to first balloon inflation time (SBT) on the 30-day and three-year rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was examined in 3,199 randomised patients according to SBT ≤3 hours versus >3 hours. Among patients with an SBT ≤3 hours, bivalirudin resulted in higher 30-day rates of MACE compared to UFH plus a GPI. Non-significant differences were observed in patients with an SBT >3 hours. Similar results were found for MACE at three years and stent thrombosis and reinfarction at 30 days and three years. By multivariable analysis, bivalirudin was an independent predictor of MACE at 30 days and three years in patients with an SBT ≤3 hours, but not in patients with SBT >3 hours.

Conclusions: Bivalirudin compared to UFH plus a GPI is associated with an increased rate of stent thrombosis and MACE in patients with short SBTs, but not in those with longer SBTs.

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) achieves optimal epicardial reperfusion in the vast majority of patients with evolving ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI); therefore, it is superior to fibrinolysis in reducing mortality, reinfarction, and stroke1. However, up to 25% of patients still experience suboptimal myocardial reperfusion associated with a negative impact on survival2, rendering improvements in adjunctive antithrombotic therapies pivotal. Several studies have shown that glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) improve myocardial perfusion and provide mortality benefits in the setting of primary PCI3; however, GPI regimens are associated with increased bleeding rates, and a prominent concern is that the prognostic implications of major bleeding complications counterbalance the treatment benefits of preventing thrombotic events4. Therefore, practice has shifted, and current guidelines recommend that GPI be reserved as bail-out therapy for thrombotic complications5. The Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial demonstrated that use of bivalirudin rather than unfractionated heparin (UFH) plus a GPI markedly reduced haemorrhagic complications, transfusions, and thrombocytopaenia and significantly improved overall and cardiac survival up to three years in patients undergoing primary PCI6.

The risk of acute stent thrombosis (ST) within the first 24 hours after stent implantation remains a concern in STEMI patients treated with bivalirudin7-9. A possible pharmacodynamic explanation is the fast reversal of bivalirudin at a time when the oral thienopyridine has not yet achieved adequate platelet inhibition. This may leave the patient without active antithrombotic protection, especially if the final angiographic result is suboptimal. Furthermore, thrombus composition changes over time from coronary occlusion, with a larger prevalence of platelets in the first hours and increasing presence of fibrin in later hours10. The outcome in patients treated with bivalirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor, or GPI, a platelet inhibitor, may therefore be determined by the time from coronary occlusion as well as the likelihood of pre-procedural antiplatelet therapy to have become effective. The aim of the current study was to evaluate whether the benefits of bivalirudin compared to UFH plus a GPI are influenced by symptom onset to first balloon inflation time (SBT).

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND POPULATION

This is a post hoc analysis of the HORIZONS-AMI trial, a prospective, open-label, randomised, multicentre study that compared 1,800 STEMI patients treated with bivalirudin alone against 1,802 STEMI patients treated with UFH plus GPI in an intention-to-treat analysis11. After emergency angiography, the management strategy was primary PCI in 3,340 (92.7%) patients, deferred PCI in 0.2%, primary coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in 1.7%, and medical management in 5.3%. At three years, follow-up data were available in 3,199 patients who underwent primary PCI, and this constituted our final target patient population.

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously11. In brief, consecutive patients >18 years of age who presented within 12 hours after onset of symptoms and who had ST-segment elevation of 1 mm or more in two or more contiguous leads, new left bundle branch block, or true posterior myocardial infarction (MI) were considered for enrolment and randomly assigned in an open-label fashion and 1:1 ratio to treatment with UFH plus a GPI (the control group) or to treatment with bivalirudin alone. UFH was administered as an intravenous bolus of 60 IU per kilogram of body weight, with subsequent boluses targeted to an activated clotting time of 200 to 250 seconds. Bivalirudin was administered as an intravenous bolus of 0.75 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 1.75 mg/kg/hr. If UFH was administered in a patient in the bivalirudin group, bivalirudin was started 30 minutes later but in all cases before PCI. Both antithrombin agents were discontinued, as specified by the protocol, at the completion of angiography or PCI but could be continued at low doses if they were clinically indicated. A GPI was administered before PCI in all the patients in the control group but was to be administered in the bivalirudin group only in patients with no reflow or with giant thrombus after PCI. Either abciximab (a bolus of 0.25 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 0.125 μg/kg/min; maximum dose, 10 μg/min) or double bolus eptifibatide (a bolus of 180 μg/kg followed by an infusion of 2.0 μg/kg/min, with a second bolus given 10 minutes after the first; no maximum dose pre-specified), adjusted for renal impairment according to the label, was permitted at the discretion of the investigator and was continued for 12 hours (abciximab) or 12 to 18 hours (eptifibatide). Aspirin (324 mg given orally or 500 mg administered intravenously) was given in the emergency room, after which 300 to 325 mg was given orally every day during the hospitalisation and 75 to 81 mg every day thereafter indefinitely. A loading dose of clopidogrel (either 300 mg or 600 mg, at the discretion of the investigator) or ticlopidine (500 mg), in the case of allergy to clopidogrel, was administered before catheterisation, followed by 75 mg orally every day for at least six months (one year or longer recommended). Clinical follow-up was performed at 30 days (±7 days), six months (±14 days), and one year (±14 days) and then yearly until three years of follow-up.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) comprised death, MI, ischaemic target vessel revascularisation, and stroke. Death from cardiac causes was defined as death due to acute MI, cardiac perforation or pericardial tamponade, arrhythmia or conduction abnormality, stroke, procedural complications, or any death for which a cardiac cause could not be ruled out. Death from non-cardiac causes included bleeding-related death. ST was defined as the definite or probable occurrence of a stent-related thrombotic event according to the Academic Research Consortium classification12. Major bleeding was defined as intracranial or intraocular haemorrhage, bleeding at the access site with a haematoma ≥5 cm or that required intervention, a decrease in the haemoglobin level of ≥4 g/dL without an overt bleeding source or ≥3 g/dL with an overt bleeding source, reoperation for bleeding, or blood transfusion. An independent clinical events committee which was unaware of the treatment assignments adjudicated all endpoint events by reviewing the medical records.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are presented as count and percentages. The continuous variables were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test and the categorical variables using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier incidence rates of the outcome variables were compared using log-rank tests. Formal interaction testing was conducted with Cox regression analysis. Multivariable predictors of MACE at 30-day and three-year follow-up within each subgroup of SBT were identified using a stepwise Cox regression with entry/stay criteria of 0.1/0.1, with the treatment variable of bivalirudin versus UFH and a GPI forced into each model. The number of covariates was carefully selected so as not to overfit the models. For the analysis of MACE at 30-day and three-year follow-up, the adjusted covariates were age, sex, race, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, current smoking, diabetes, history of congestive heart failure (CHF), prior PCI, prior CABG, number of stents implanted, pre-PCI Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow, and post-PCI TIMI flow. The proportional hazards assumption was checked for the Cox model by creating interactions of the predictors and a function of survival time, and none was found to be significant. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

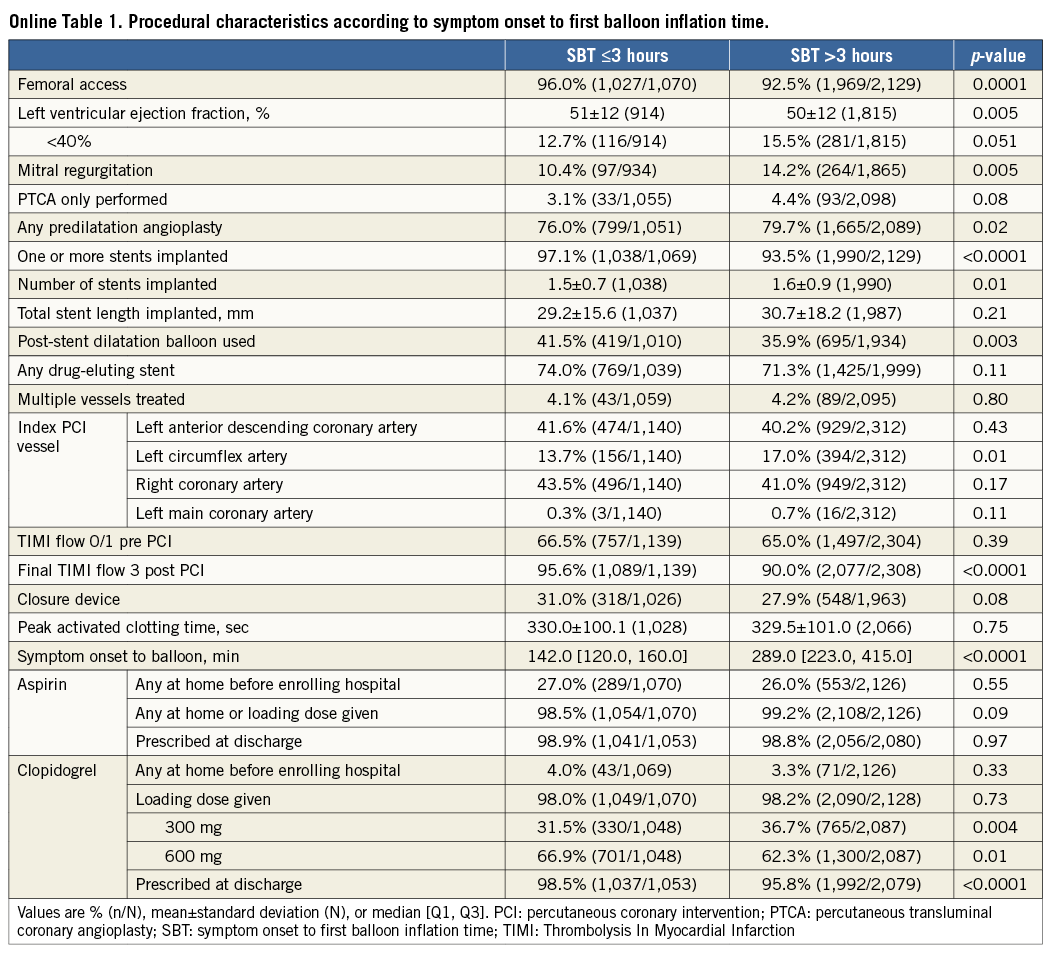

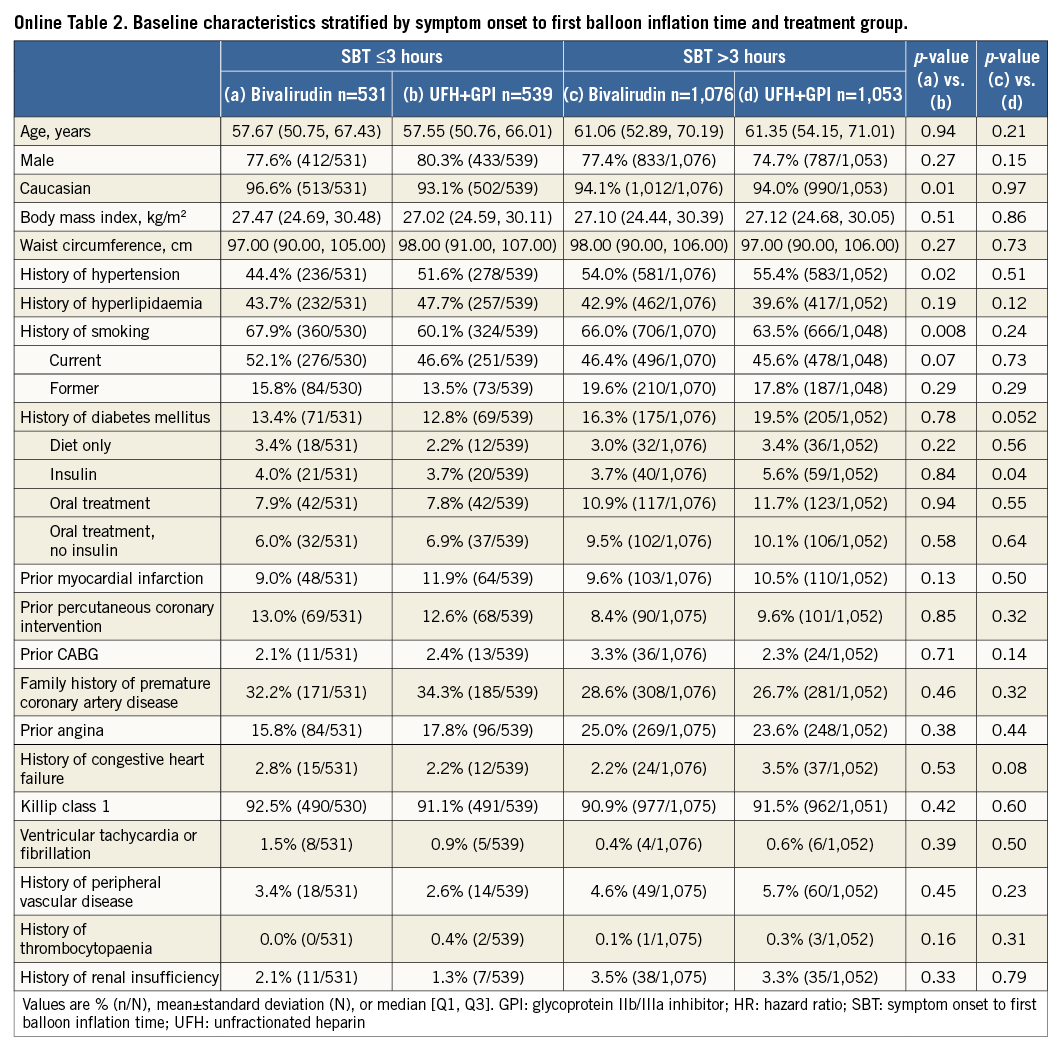

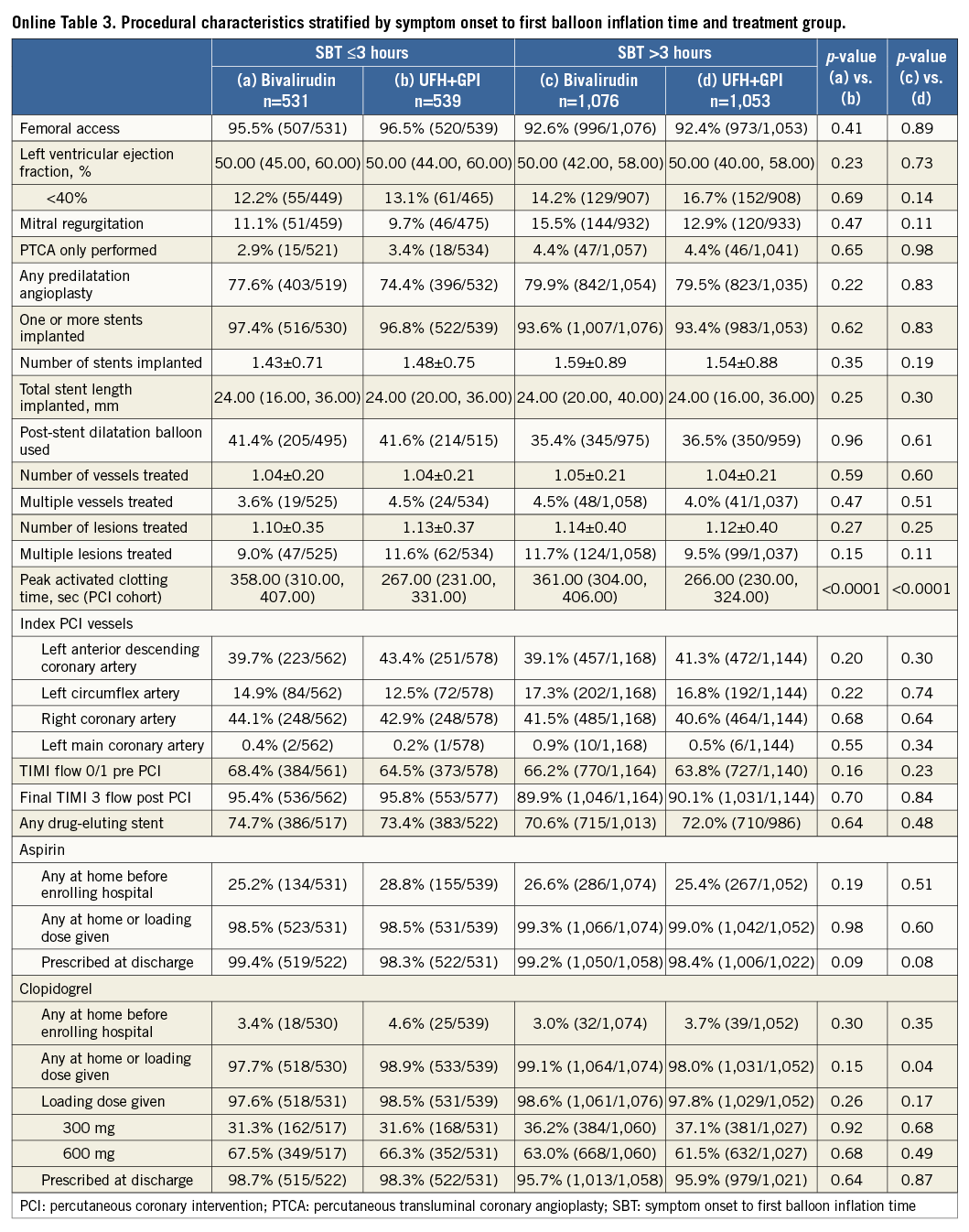

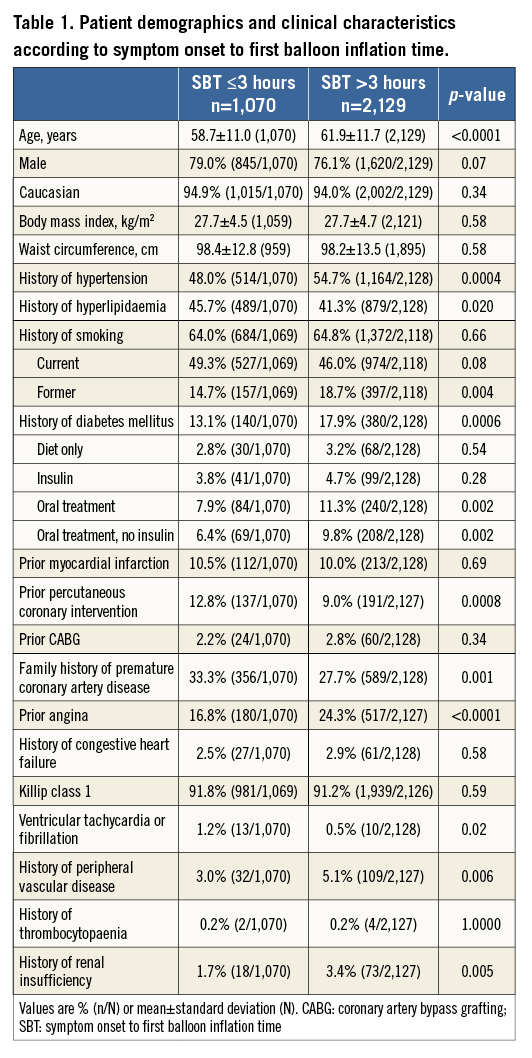

Patients were stratified by SBT ≤3 hours or >3 hours. Patients with an SBT >3 hours were older and more likely to be former smokers and have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prior angina, peripheral vascular disease, renal insufficiency, impaired left ventricular ejection fraction, and mitral regurgitation at admission; they were also more likely to have the left circumflex as the culprit artery and had more stents implanted. Conversely, patients with SBT >3 hours were less likely to have undergone previous PCI or have a family history of premature coronary artery disease. They were also less likely to obtain good epicardial coronary flow at the end of procedure (TIMI flow 3) and to be preloaded with 600 mg clopidogrel (Table 1, Online Table 1). There were no important discrepancies in baseline and procedural variables between treatment groups within each time category (Online Table 2, Online Table 3).

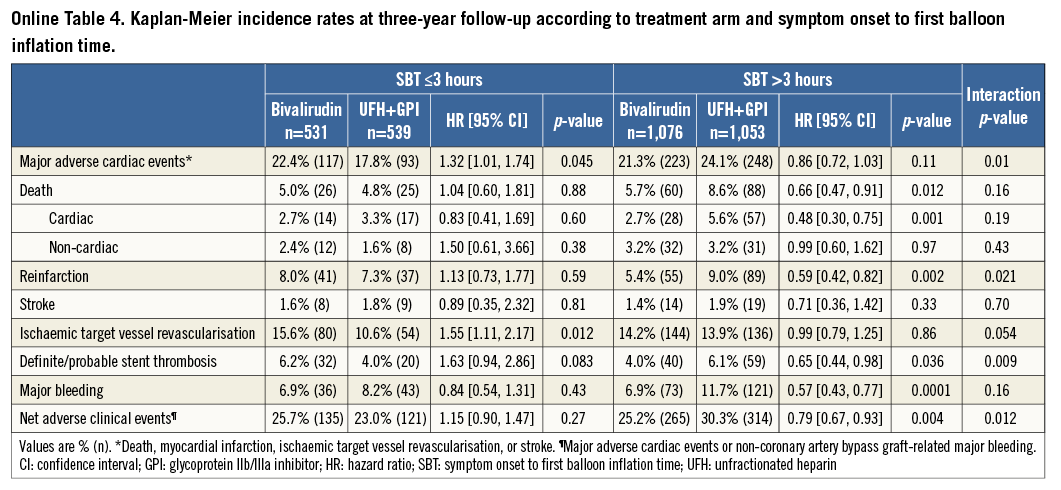

A total of 162 (5.1%) episodes of MACE had occurred at 30-day follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves of adverse events are depicted in Figure 1-Figure 4. Bivalirudin was associated with a significantly higher incidence of MACE compared to UFH plus a GPI among patients with an SBT ≤3 hours (6% vs. 3%, hazard ratio [HR]: 2.08, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.14 to 3.79, p=0.02), whereas no significant difference but a change in the direction of the risk was observed among patients with an SBT >3 hours (4.7% vs. 6.1%, HR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.53 to 1.11, p=0.16). We found significant SBT by treatment arm interaction for MACE at 30-day follow-up (p=0.005). This risk reversal towards a beneficial effect of bivalirudin with increasing ischaemic time was primarily driven by recurrent myocardial infarction and definite or probable ST, both with significant treatment group by SBT interaction, whereas the risk of stroke remained uniform regardless of SBT. The beneficial effects of bivalirudin in terms of cardiac death and bleeding were only evident in the group with higher SBT (Table 2). These same patterns remained at three-year follow-up (Online Table 4).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank p-values for the incidence estimates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at three-year follow-up in patients treated with bivalirudin compared to patients treated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) according to symptom onset to first balloon inflation time (SBT).

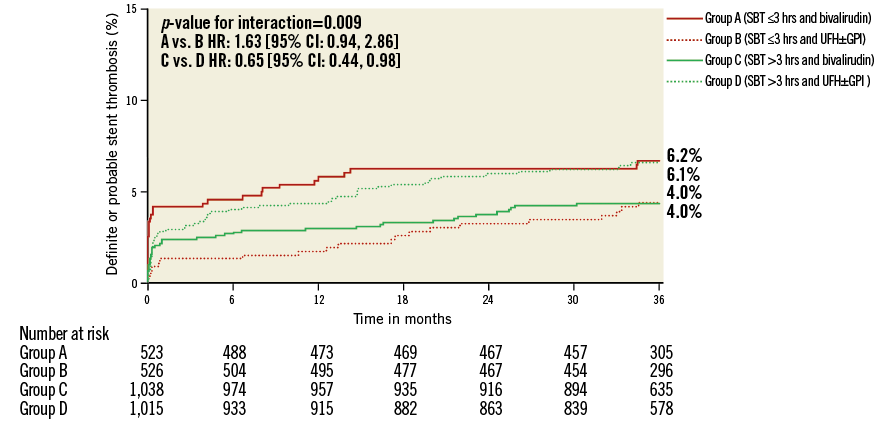

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank p-values for the incidence estimates of definite or probable stent thrombosis at three-year follow-up in patients treated with bivalirudin compared to patients treated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) according to symptom onset to first balloon inflation time (SBT).

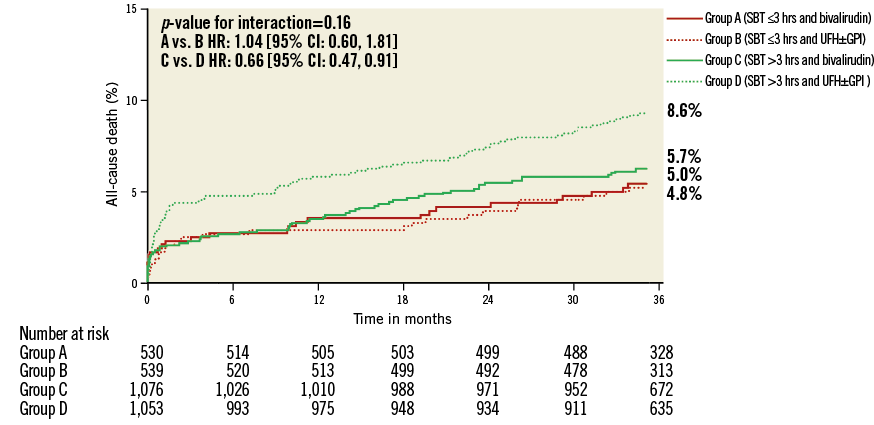

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank p-values for the incidence estimates of all-cause death at three-year follow-up in patients treated with bivalirudin compared to patients treated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) according to symptom onset to first balloon inflation time (SBT).

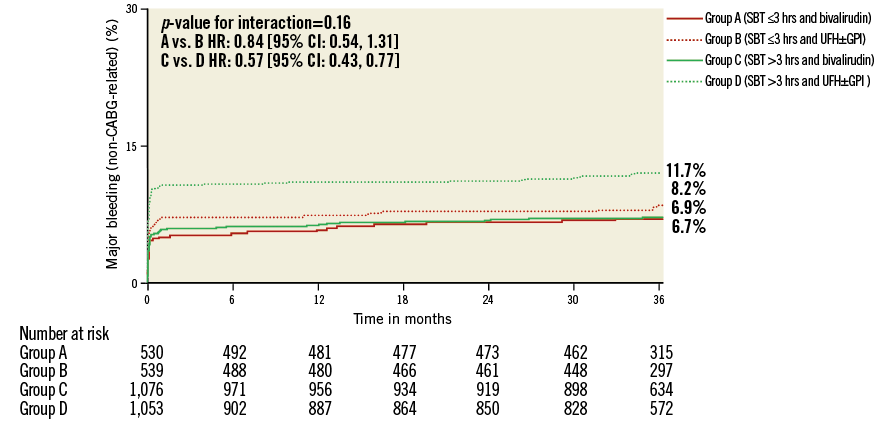

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank p-values for the incidence estimates of major bleeding at three-year follow-up in patients treated with bivalirudin compared to patients treated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) and provisional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) according to symptom onset to first balloon inflation time (SBT).

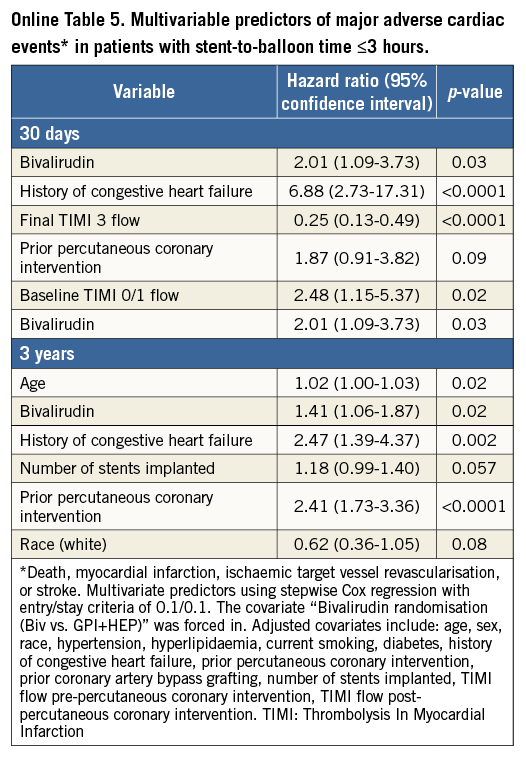

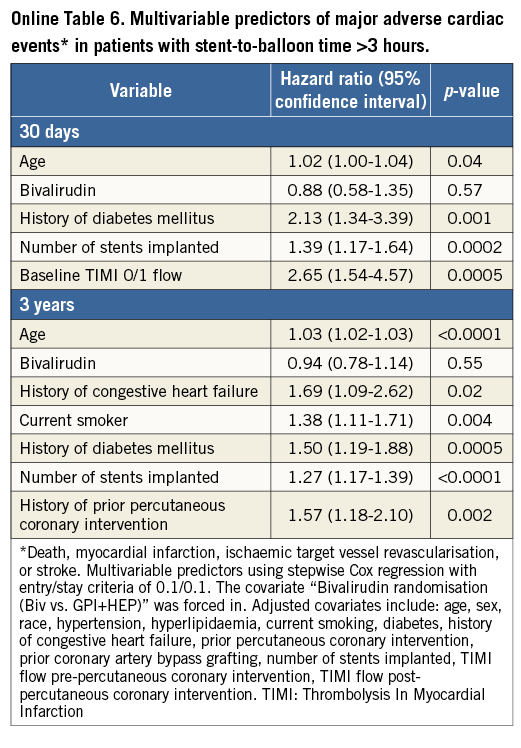

Among 74 (2.4%) definite or probable ST diagnosed at 30 days, only acute ST occurring within the first 24 hours after primary PCI was significantly increased in patients treated with bivalirudin and short ischaemic time (≤3 hours). Bivalirudin was associated with a 3.4-fold risk of acute definite or probable ST. No difference among treatment groups was seen for acute ST in patients treated >3 hours after symptom onset or in subacute ST regardless of SBT. After adjustment, bivalirudin remained a predictor of MACE at 30 days (HR: 2.09, 95% CI: 1.13 to 3.88, p=0.026) and three-year follow-up (HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.87, p=0.019) in patients with an SBT ≤3 hours. Other predictors were history of CHF and baseline and final TIMI 3 flow at 30-day follow-up. At three-year follow-up, the predictors were history of CHF, prior PCI, and age (Online Table 5).

In patients with an SBT >3 hours, age, diabetes, multiple stent implantation, and baseline TIMI flow 0/1 predicted MACE at 30-day follow-up but bivalirudin did not (HR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.58 to 1.35, p=0.57). At three-year follow-up, predictors were age, diabetes, current smoking, number of stents implanted, and history of CHF, whereas bivalirudin was not associated (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.78 to 1.14, p=0.55) (Online Table 6).

Major non-CABG-related bleeding occurred in 229 (7.2%) patients at 30 days. Among patients with an SBT ≤3 hours, bivalirudin was numerically associated with a beneficial bleeding profile (4.9% vs. 6.9%, HR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.43 to 1.17, p=0.17), which improved to significant levels in patients with an SBT >3 hours (5.5% vs. 10.2%, HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.38 to 0.72, p<0.0001) without positive interaction (Table 2). A similar pattern was observed at three-year follow-up and resulted in positive interaction testing for SBT by treatment arm in regard to net adverse clinical events (Online Table 4).

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that the net clinical benefit of bivalirudin in comparison to UFH plus a GPI depends on SBT in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI. In patients treated ≤3 hours from symptom onset, bivalirudin was associated with increased rates of MACE, with a 2.5-fold increased hazard of reinfarction and ischaemia-driven target vessel revascularisation and a 3.5-fold increased risk of acute ST. This risk pattern was inverted in patients treated >3 hours after symptom onset to a numerically higher incidence of MACE in patients treated with UFH plus a GPI. The previously reported long-term safety benefits of bivalirudin in terms of major bleeding and mortality only became apparent in patients with an SBT >3 hours.

To date, HORIZONS-AMI11 is the largest randomised, multicentre study conducted on STEMI patients comparing bivalirudin to a strategy of UFH plus a GPI. This study showed a significant reduction in mortality, MI, ST, and major bleeding complications in the bivalirudin arm, which led to a class I guideline recommendation in primary PCI5; however, the present analysis indicates a delayed onset of the bivalirudin treatment effect, with a more favourable outcome associated with UFH plus a GPI within the first three hours from symptom onset. The EUROMAX trial, which examined pre-hospital administration of bivalirudin in comparison to UFH plus a GPI, confirmed the beneficial bivalirudin profile in terms of major bleeding, but did not find the same mortality reduction. An unexplored explanation could lie in the present finding of a time dependency of the bivalirudin effect, as bivalirudin was given at an earlier time point in the patients’ symptom course in the EUROMAX trial8. Furthermore, recent results from the Early Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa Inhibitors in Primary Angioplasty (EGYPT) database indicate that the shorter the time delay from symptom onset to GPI, the more favourable the outcome in regard to pre-procedural TIMI flow 3, myocardial perfusion, distal embolisation, and long-term survival13.

The recently published Bivalirudin in Acute Myocardial Infarction vs. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and Heparin (BRIGHT) trial randomly assigned patients to receive bivalirudin with post-PCI infusion, UFH alone, or UFH plus tirofiban with a post-PCI infusion. All patients were exclusively loaded with clopidogrel and aspirin. The investigators demonstrated a decrease in net adverse clinical events compared with heparin alone and heparin plus tirofiban. This finding was due to a reduction in any bleeding with bivalirudin without significant differences in MACE or ST14. The Unfractionated Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (HEAT-PPCI) trial, a single-centre randomised controlled trial of STEMI patients treated with either bivalirudin or UFH and similar use of abciximab as bail-out strategy in both arms, reported the primary efficacy outcome of MACE and ST to be more common in the bivalirudin group. Major or minor bleeding was similar between the groups9. While the reduction in bleeding is a constant benefit seen with bivalirudin, EUROMAX, HEAT-PPCI, and BRIGHT were all not able to replicate the mortality reduction seen in HORIZONS-AMI. These trials have also been pooled in a meta-analysis without being able to find a relationship between the reduction in bleeding and death15. Our results demonstrate that the survival benefit with bivalirudin in HORIZONS-AMI was only present in patients treated later than three hours from symptom onset.

A further explanation for these conflicting results could lie in the pharmacodynamic profile of bivalirudin, with its fast reversal (within one to two hours) at a time when the oral thienopyridine has not yet achieved adequate platelet inhibition (≈6 hours). This might be especially true in acute MI, where intraprocedural thrombotic events are frequent and lead to suboptimal post-procedural epicardial flow and myocardial perfusion which result in adverse outcomes16. In HORIZONS-AMI, patients were almost exclusively loaded with clopidogrel, while the more recent HEAT-PPCI and EUROMAX trials used ticagrelor and prasugrel in approximately 90% and 50% of patients, respectively. The delayed onset of clopidogrel is a well-known phenomenon and is related to the high inter-individual variability in platelet response to clopidogrel17. The combination of clopidogrel with bivalirudin might therefore leave some patients insufficiently protected against platelet aggregation in the early phase after symptom onset. The rate of 600 mg clopidogrel loading dose did not differ between treatment arms within each time stratum (Online Table 3).

In comparison to clopidogrel, ticagrelor and prasugrel have less inter-individual variability17 and provide better antiplatelet protection18,19; however, at least four hours are required to achieve an effective platelet inhibition in the majority of patients20. Prasugrel has recently been associated with improved efficacy, including ST, and similar safety compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing primary PCI with bivalirudin21. Pre-hospital administration of ticagrelor in STEMI patients did not increase ST resolution or TIMI flow 3 at initial angiography in the infarct-related artery, but did decrease ST at 30-day follow-up22.

Several studies seem to support that administration of UFH along with bivalirudin may be required to reduce acute thrombotic events23,24. Furthermore, patients who switched from pre-procedural UFH to bivalirudin during procedure experienced fewer bleeding complications in the HORIZONS-SWITCH analysis23, while bleeding did not differ between the bivalirudin group and the bivalirudin plus UFH group in the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR)24.

It is questionable whether the risk of ST is ameliorated by post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin. Although the post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin was previously reported to be beneficial14,25, the recent randomised MATRIX trial specifically investigated a regimen with post-PCI infusion of bivalirudin for at least four hours and did not find any reduction in the composite outcome of ischaemic and bleeding events, including stent thrombosis26.

An alternative or synergistic reason for our findings could be the evolution of thrombus composition over time from initial coronary occlusion to reperfusion, with a larger prevalence of platelets in the first hours compared to an increasing presence of fibrin in later hours9. Therefore, administration of a more potent intravenous antiplatelet therapy with GPI is expected to be beneficial within the first hours from symptom onset27,28, while bivalirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor, might be more beneficial in patients with higher ischaemic times.

A further candidate strategy to overcome the early thrombotic hazard in bivalirudin-treated patients could be an upstream bolus of cangrelor29.

The treatment benefit of bivalirudin in reducing major bleeding complications was accentuated in patients treated >3 hours from symptom onset, despite their more severe risk profile including known risk factors for bleeding such as higher age and renal insufficiency30. This indicates that the beneficial effect of bivalirudin in bleeding reduction is increased in patients with elevated bleeding risk, which is in accordance with the results of a large meta-analysis that studied the impact of baseline haemorrhagic risk on the benefit of bivalirudin31.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. HORIZONS-AMI had an open-label design, which could have introduced potential bias; however, compliance with the protocol procedure and the study medications was high, and the rate of provisional use of GPI in the bivalirudin group was low and similar to that in the double-blind Randomized Evaluation in PCI Linking Angiomax to Reduced Clinical Events (REPLACE-2) trial32. The study was conducted with clopidogrel, whereas prasugrel and ticagrelor are currently recommended as first choice adenosine diphosphate therapy in the setting of STEMI5. In HORIZONS-AMI, primary PCI was performed by the femoral access, whereas the increasingly routine use of radial access might be particularly beneficial in STEMI patients33. Despite the positive interaction, the observation that SBT is an effect modifier of bivalirudin efficacy compared to treatment with UFH with or without a GPI should be considered hypothesis-generating and not causal.

Conclusion

SBT modifies the effect of bivalirudin in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. In patients treated within three hours of symptom onset, a combination of UFH and GPI was associated with a reduced incidence of MACE and acute ST in comparison to bivalirudin. Bivalirudin was associated with less cardiac mortality and major bleeding in patients treated >3 hours after symptom onset.

| Impact on daily practice In patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention, anticoagulation with bivalirudin is known to lead to better bleeding outcomes but a higher incidence of acute stent thrombosis compared to a regimen of unfractionated heparin and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. This study indicates that time to treatment is an effect modifier of these antithrombotic regimens: patients with a short symptom-to-balloon time (<3 hours) appear to benefit more from a regimen with unfractionated heparin and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, whereas patients with longer delays draw more benefit from a bivalirudin regimen. These results may be a function of the pharmacodynamics of antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatment strategies and changing thrombus composition over time. |

Conflict of interest statement

R. Mehran and G. Dangas receive research grant support from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, The Medicines Company, BMS/Sanofi-Aventis, and are consultants for AstraZeneca, Bayer, CSL Behring, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Osprey Medical Inc., Watermark Research Partners (modest <$5,000/yr). They are on the scientific advisory board of Abbott Laboratories, Boston Scientific, Covidien, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, The Medicines Company, Sanofi-Aventis, and give industry-sponsored lectures. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data