Abstract

Aims: We aimed to assess the association of bivalirudin with post-procedural Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow, acute (≤24 hours) and 30-day stent thrombosis (ST), and one-year mortality.

Methods and results: The study included 11,623 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The primary outcomes were post-procedural TIMI flow grade ≤2 and definite acute ST. In groups treated with bivalirudin (n=3,135), abciximab plus unfractionated heparin (UFH; n=3,539) and UFH alone (n=4,949), post-procedural TIMI was ≤2 in 5.2%, 3.2% and 3.2% of patients, respectively (adjusted odds ratio [OR]=1.96 [95% confidence interval] 1.47-2.56 for bivalirudin versus abciximab plus UFH and OR=1.56 [1.20-2.04] for bivalirudin versus UFH). Definite acute ST occurred in two patients (0.06%) treated with bivalirudin, two patients (0.06%) treated with abciximab plus UFH, and seven patients (0.14%) treated with UFH (p=0.47). Bivalirudin was not associated with increased risk of 30-day ST (hazard ratio [HR]=1.20 [0.59-2.43] versus abciximab plus UHF, and HR=0.93 [0.48-1.82] versus UFH) or one-year mortality (HR=0.95 [0.70-1.28] versus abciximab plus UHF, and HR=1.05 [0.78-1.41] versus UFH).

Conclusions: Bivalirudin was associated with higher risk of suboptimal post-PCI TIMI flow but not with increased risk of acute or 30-day definite ST or one-year mortality compared with abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone.

Introduction

Bivalirudin has been considered a viable alternative to unfractionated heparin (UFH) alone or in combination with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor as an anticoagulant strategy during percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). Although the use of bivalirudin is associated with a significant reduction of major bleeding, its impact on ischaemic complications and mortality remains controversial1,2. In the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) trial, bivalirudin, as compared with UFH with routine use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI), was associated with reduced incidence of 30-day major bleeding and cardiac and all-cause mortality1. In the European Ambulance Acute Coronary Syndrome Angiography (EUROMAX) trial, pre-hospital bivalirudin reduced the risk of major bleeding, but it had no impact on 30-day mortality or reinfarction compared with UFH (or low-molecular weight heparin) plus optional GPI2. In both studies, the risk of acute stent thrombosis (ST) was increased by bivalirudin compared with UFH with or without a GPI in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. More than one third of all ST during three-year follow-up occurred during the hospital phase, and mortality and major bleeding were significantly higher after in-hospital stent thrombosis (more specifically subacute thrombosis) compared with out-of-hospital stent thrombosis3.

Restoration of Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 3 by PCI is achieved in up to 95% of patients4-6. Failure to restore optimal epicardial blood flow is associated with worse clinical outcome including early and late mortality4,7-9. Of note, it has been shown that suboptimal post-PCI epicardial blood flow (TIMI flow grade ≤2) is associated with an increased risk for ST10,11. Thus, the investigation of the impact of bivalirudin on procedural success and, in particular, on the post-PCI TIMI flow is of clinical interest. We undertook this study to compare the impact of various peri-PCI anticoagulant strategies (bivalirudin, abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone) on the restoration of TIMI flow, acute (≤24 hours) and 30-day risk of ST, and one-year mortality.

Methods

PATIENTS

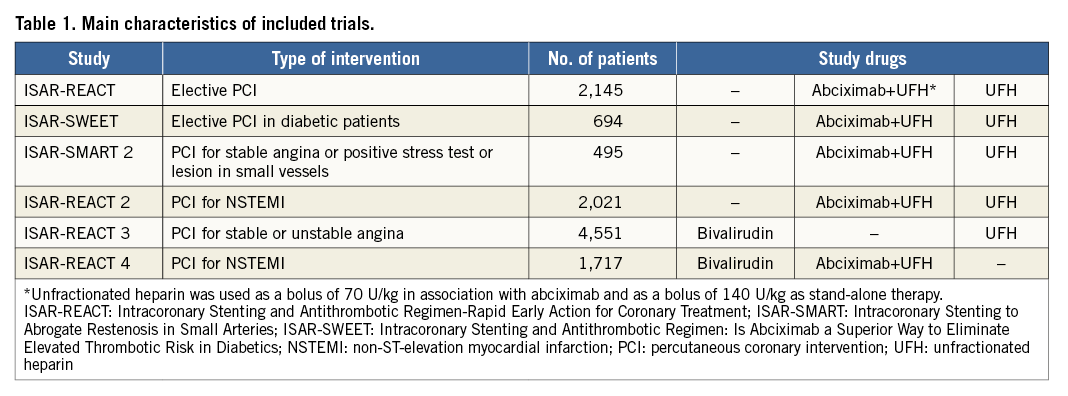

The study sample comprised 11,623 patients recruited in six randomised clinical trials (Table 1)12-17. All patients were recruited between June 2000 and May 2011. Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria are provided in the primary publications12-17. Cardiovascular risk factors were defined using the accepted criteria. Written informed consent was required for participation in the primary trials, and an institutional review board approved each study at each participating centre.

ANTITHROMBOTIC/ANTICOAGULANT DRUG REGIMENS

Patients underwent PCI after receiving 325-500 mg of aspirin and a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel, at least two hours before the procedure. Details of the use of antithrombotic/anticoagulant drugs were provided in source publications12-17. In brief, antithrombotic/anticoagulant drugs (applied in double-blind fashion) included: abciximab – an intravenous bolus of 0.25 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 0.125 µg/kg/min (a maximum of 10 µg/min) for 12 hours in combination with UFH (a bolus of 70 U/kg); UFH – an intravenous bolus of 140 U/kg and bivalirudin – an intravenous bolus of 0.75 mg/kg, followed by an infusion of 1.75 mg/kg per hour until the end of the procedure. Overall, there were 3,135 patients randomised to bivalirudin, 3,539 patients randomised to abciximab+UFH 70 U/kg, and 4,949 patients randomised to UFH 140 U/kg.

Coronary stenting with either bare metal or drug-eluting stents was performed as per standard practice. The femoral artery route was used for vascular access. Sheaths were removed and manual compression was applied as soon as the activated partial thromboplastin time fell below 50 seconds. Chronic post-PCI antiplatelet therapy consisted of aspirin (80-325 mg per day indefinitely) and clopidogrel (75 to 150 mg per day until discharge but for no longer than three days, followed by 75 mg per day for ≥1 month in patients with bare metal stents or ≥6 months in patients with drug-eluting stents). Other cardiac medications were prescribed at the discretion of the attending physician.

STUDY OUTCOMES AND DEFINITIONS

The primary outcomes were post-procedural TIMI flow grade ≤2 at the target vessel and acute (≤24 hours) ST. The secondary outcomes were definite ST at 30 days and all-cause mortality at one year after PCI. Epicardial blood flow was quantified according to the TIMI group criteria18. Definite ST was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria19. The diagnosis of myocardial infarction required the development of new abnormal Q-waves in ≥2 contiguous precordial or ≥2 adjacent limb leads or an elevation of creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB) >2 times (>3 times for the 48 hours after a PCI procedure) the upper limit of normal. Bleeding events within the 30 days after PCI were defined using the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria20. Information on deaths was obtained from hospital records, death certificates or phone contact with the referring physician(s), relatives of the patient, insurance companies and registration of address office.

The follow-up protocol included a phone interview at one month, a visit at six months and a phone interview at 12 months. Collection of follow-up information and adjudication of adverse events were performed by medical staff unaware of the type of treatment received. Angiographic data were analysed by the same quantitative angiographic core laboratory, located at the ISAResearch Center, Munich.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The normality of data distribution was tested using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Data are presented as median (25th-75th percentiles), mean±standard deviation, counts (%) or Kaplan-Meier estimates (%). Categorical data were compared with the chi-square test. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. The heterogeneity of odds ratios was assessed with the Breslow-Day test. A multiple logistic regression model was used to assess correlates of post-PCI TIMI flow. The following variables were entered into the model: antithrombotic therapy, age, sex, body mass index, diabetes, arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, current smoking, prior myocardial infarction, presentation with an acute coronary syndrome, elevated troponin, multivessel disease, intervention in a venous bypass graft, complex lesions, baseline TIMI flow, number of lesions and type of intervention. Bootstrapping (400 samples) was used to validate the stability of the model by ensuring the fidelity of the confidence intervals. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess correlates of definite ST at 30 days and one-year mortality. The same variables as for the model for post-PCI TIMI flow were entered into the Cox models. Due to collinearity with the number of lesions, the number of stents and total stented length were not entered into the models. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by the method of Grambsch and Therneau21. All analyses were performed using the R package. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

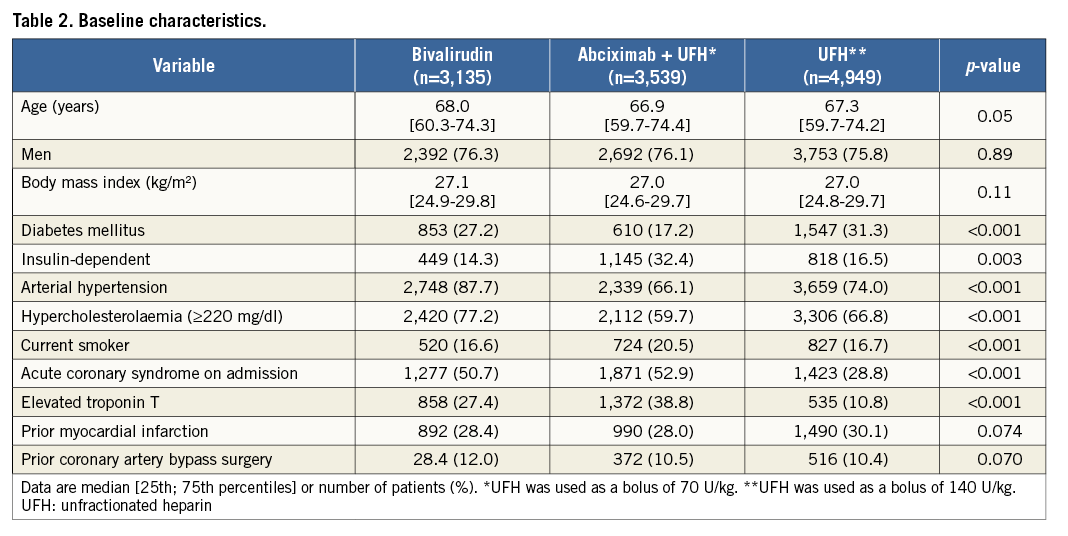

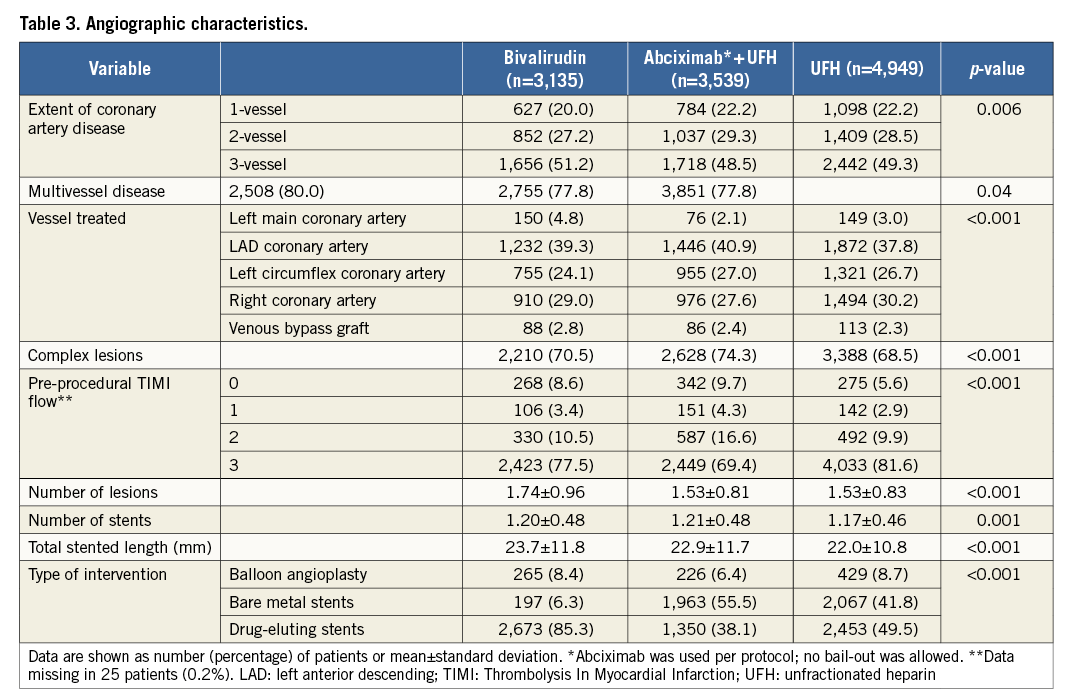

According to the antithrombotic/anticoagulant strategy received, patients were divided into three groups: abciximab plus UFH group (n=3,539), bivalirudin group (n=3,135), and UFH alone group (n=4,949). Coronary stents were implanted in 10,703 patients (92.1%). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2. There were significant differences among the groups with regard to proportion of patients with diabetes (including those requiring insulin), arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking status, acute coronary syndrome on admission and elevated troponin T level. Angiographic and procedural characteristics are shown in Table 3.

ANGIOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL OUTCOMES

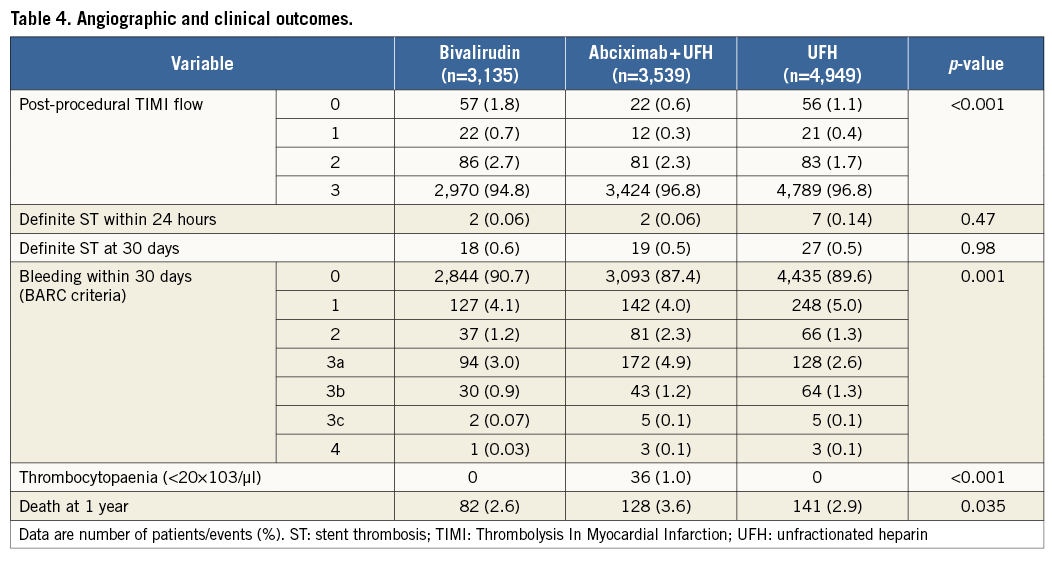

Angiographic and clinical outcomes are shown in Table 4. In patients treated with bivalirudin, abciximab plus UFH and UFH alone, the frequency of post-procedural TIMI flow grade ≤2 was 5.2%, 3.2% and 3.2%, respectively, showing a significantly higher rate of TIMI flow grade ≤2 among patients treated with bivalirudin compared with abciximab plus UFH (odds ratio [OR]=1.65, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.30-2.11, p<0.001) or UFH alone (OR=1.66 [1.33-2.08], p<0.001). In the Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen-Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (ISAR-REACT) 3 trial, in which bivalirudin was compared with UFH, the incidences of TIMI flow ≤2 were 4.7% in the bivalirudin group and 4.2% in the UFH group (OR=1.16 [0.86-1.54]; the Breslow-Day test for the heterogeneity of ORs showed a p-value of 0.044 for the association of this OR with the OR for this association in the overall study). In the ISAR-REACT 4 trial, in which bivalirudin was compared with abciximab plus UFH, the incidences of TIMI flow ≤2 were 6.4% in the bivalirudin group and 5.9% in the UFH group (OR=1.08 [0.72-1.64]; the Breslow-Day test for the heterogeneity of ORs showed a p-value of 0.075 for the association of this OR with the OR for this association in the overall study). Definite ST <24 hours after PCI occurred in two patients (0.06%) treated with bivalirudin, two patients (0.06%) treated with abciximab plus UFH, and seven patients (0.14%) treated with UFH alone (p=0.47). Definite ST at 30 days occurred in 64 patients: 18 patients (0.6%) in the bivalirudin group, 19 patients (0.5%) in the abciximab plus UFH group, and 27 patients (0.5%) in the UFH alone group (p=0.98). There were 351 deaths at one year after PCI: 82 deaths (2.6%) among patients treated with bivalirudin, 128 deaths (3.6%) among patients treated with abciximab plus UFH, and 141 deaths (2.9%) among patients treated with UFH alone (log-rank test p=0.035). Among patients treated with bivalirudin, the risk of death was lower than in patients treated with abciximab plus UFH (OR=0.72 [0.54-0.95], p=0.019), but similar to that in those treated with UFH alone (OR=0.91 [0.70-1.21], p=0.53). Other clinical outcomes are shown in Table 4.

PREDICTORS OF POST-PCI TIMI FLOW, 30-DAY ST AND ONE-YEAR MORTALITY

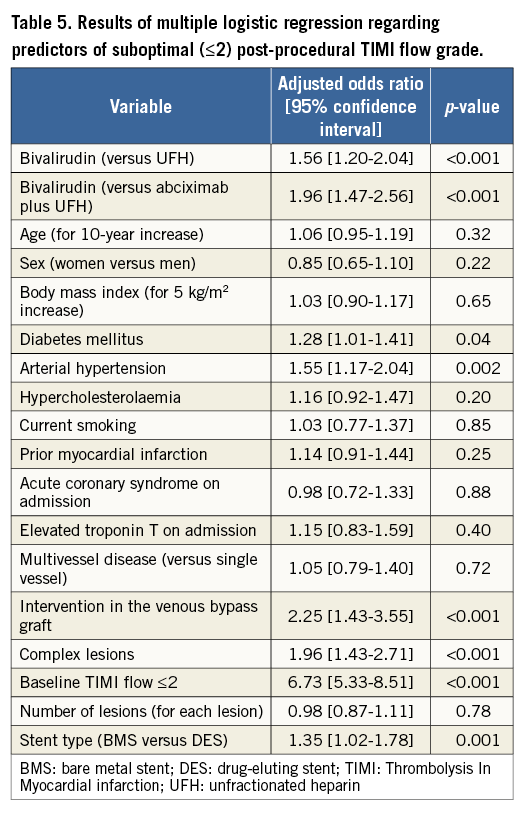

The multiple logistic regression model showed that bivalirudin use, diabetes, arterial hypertension, intervention in a venous bypass graft, complex lesions, pre-procedural TIMI flow ≤2 and stent type were associated with the increased risk of post-PCI TIMI flow ≤2 (Table 5).

The bootstrapping approach confirmed the stability of the multiple logistic regression model for the association with TIMI flow ≤2 of bivalirudin vs. UFH (OR=1.96 [1.45-2.63]) or bivalirudin vs. abciximab plus UFH (OR=1.56 [1.18-2.06]). Due to the limited number of events, multivariable analysis was not applied to identify correlates of risk for acute ST.

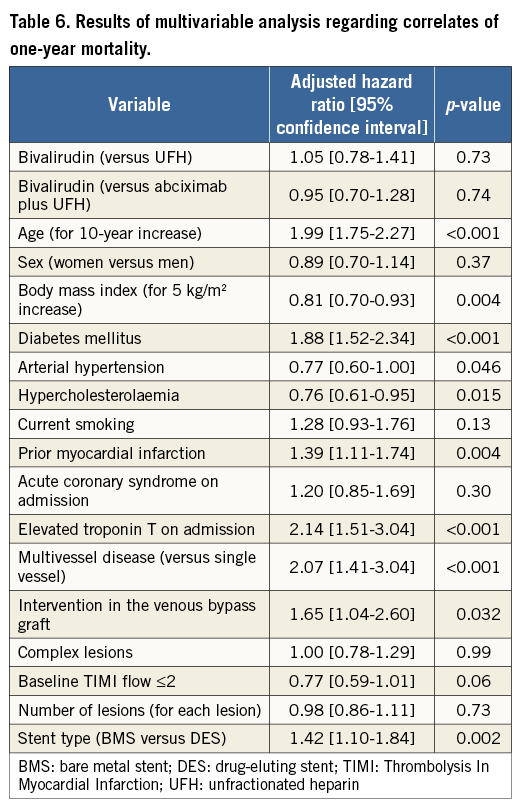

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify associates of risk for 30-day ST and one-year mortality. Diabetes (hazard ratio [HR]=2.37 [1.41-3.96], p<0.001) and number of lesions (HR=1.63 [1.32-2.01], p<0.001) were the only variables that were associated with the increased risk of 30-day ST. Bivalirudin use was not associated with an increased risk of 30-day ST compared with abciximab plus UFH (HR=1.20 [0.59-2.43]) or UFH alone (HR=0.93 [0.48-1.82]). The results of the Cox model applied to identify associates of one-year mortality are shown in Table 6. Bivalirudin use was not associated with an increased risk of one-year mortality compared with abciximab plus UFH (HR=0.95 [0.70-1.28]) or UFH alone (HR=1.05 [0.78-1.41]).

Discussion

The main findings of this study may be summarised as follows. 1) The use of bivalirudin as peri-PCI anticoagulant strategy in patients with stable coronary artery disease and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes is associated with a higher frequency of post-procedural suboptimal epicardial blood flow (TIMI flow grade ≤2) compared with a strategy of abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone. 2) Peri-PCI use of bivalirudin in patients with stable or unstable coronary artery disease was not associated with increased risk of acute (≤24 hours) or 30-day ST compared with a strategy of abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone. 3) Periprocedural use of bivalirudin was not associated with an increased adjusted risk of one-year mortality as compared with abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone.

Suboptimal epicardial coronary flow after PCI is multifactorial. Various factors, including patient’s characteristics (older age, history of myocardial infarction, anterior wall infarct, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, haemodynamic instability) or procedure-related factors (pre-procedural TIMI flow grade 0-1, persistent stenosis or thrombosis, coronary dissection, intramural haematoma, side branch occlusion, coronary spasm or distal embolisation of thrombotic material)7,8,22,23, have been found to increase the risk of suboptimal epicardial flow after PCI. One observational study in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with PCI has reported better post-procedural TIMI flow but no difference in bleeding events, angiographic no-reflow or 30-day incidence of major adverse cardiac events with bivalirudin with provisional use of glyocoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors versus UFH with provisional use of GPI24. To our knowledge, the finding of an association between bivalirudin use and an increased risk of suboptimal post-procedural TIMI flow has not been reported before. Although the possibility that this finding is a play of chance cannot be entirely refuted, several lines of evidence may support such an association. First, since patients treated with bivalirudin did not have a worse profile in terms of baseline cardiovascular risk or patient- or procedure-related characteristics compared to patients treated with abciximab or UFH, differences in the risk profile do not seem to explain the differences among various antithrombotic strategies in the restoration of post-PCI TIMI flow. Second, the association between bivalirudin use and an increased risk of suboptimal epicardial blood flow restoration by PCI persisted after adjustment for potential confounders. Third, prior studies have suggested an inverse relationship in the bivalirudin impact on bleeding and thrombotic complications after PCI, i.e., a greater reduction of bleeding risk with bivalirudin, at the expense of a lower protection against thrombotic complications with the drug25. Fourth, studies in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction have reported an increased risk of acute (≤24 hours) ST with bivalirudin compared with UFH with routine or optional use of GPI1,2, which may be interpreted as an indication of suboptimal antithrombotic protection.

The present study did not show any increase in the risk of ST with bivalirudin compared to other antithrombotic/anticoagulant periprocedural strategies used, albeit the number of events (especially acute stent thrombosis) was limited. In this regard, the present findings seem to differ from the recent studies that have reported an increased risk of acute ST with bivalirudin compared to UFH with routine or optional use of GPI1,2. These studies have reported an increased risk of acute ST in patients with STEMI, known to have a high thrombotic burden and increased thrombogenicity. Conversely, the present study included patients with stable angina undergoing elective PCI or non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes with less thrombogenic potential at the site of the target vessel. The increased risk of ST associated with suboptimal post-procedural epicardial blood flow10,11 might have been counterbalanced by a reduction in peri-PCI bleeding, which has been reported to increase the risk of ST significantly26.

Consistent with other studies27, we did not find any impact of bivalirudin on mortality as compared with abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone strategies. The association of bivalirudin with the risk of mortality may be complex. On the one hand, bivalirudin use was associated with an increased risk of suboptimal epicardial blood flow after PCI, known to be a significant associate of mortality after PCI8,9. On the other hand, the present study and other studies1,17,27 have shown that bivalirudin use is associated with a significant reduction of the risk of peri-PCI bleeding. Thus, in terms of the association with mortality, as well as with ST, the impact of worse post-procedural epicardial flow might have been counterbalanced by the reduction of bleeding by bivalirudin.

Limitations

The present study has limitations. First, although the study patients were obtained from randomised trials, the present pooled analysis, in itself, does not represent a randomised comparison of antithrombotic strategies. Second, due to the long study period, changes in the practice of PCI involving new antithrombotic therapy and stent technology have occurred; however, in the setting of the present study they remain difficult to assess. Although we adjusted for differences in the baseline data in the multivariable analysis, there is a possibility that some confounders remain unaccounted for. Third, the number of acute ST was too small to allow an analysis of factors predisposing for this complication. Likewise, caution is warranted in interpreting the correlates of 30-day ST due to the limited number of this adverse event.

Conclusions

In conclusion, bivalirudin use as a peri-PCI anticoagulant strategy in patients with stable and unstable coronary artery disease was associated with an increased risk of post-procedural suboptimal epicardial blood flow compared with a strategy of abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone. However, in direct comparison trials of bivalirudin, the difference in outcome was less pronounced. Bivalirudin was not associated with an increased risk of acute or 30-day ST or one-year mortality compared with abciximab plus UFH or UFH alone.

| Impact on daily practice Failure to restore optimal epicardial blood flow post-PCI is multifactorial and associated with worse clinical outcome. The periprocedural use of bivalirudin compared to UFH or UFH plus abciximab increases the risk of suboptimal epicardial blood flow. Thus, in daily PCI routine, the choice of periprocedural anticoagulant regimen should be reflected on thoroughly, and balance the patient’s individual risks for ischaemic and bleeding events. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.