Abstract

Aims: Early-generation drug-eluting stent (DES) overlap (OL) is associated with impaired long-term clinical outcomes whereas the impact of OL with newer-generation DES is unknown. Our aim was to assess the impact of OL on long-term clinical outcomes among patients treated with newer-generation DES.

Methods and results: We analysed the three-year clinical outcomes of 3,133 patients included in a prospective DES registry according to stent type (sirolimus-eluting stents [SES; N=1,532] versus everolimus-eluting stents [EES; N=1,601]), and the presence or absence of OL. The primary outcome was a composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), and target vessel revascularisation (TVR). The primary endpoint was more common in patients with OL (25.1%) than in those with multiple DES without OL (20.8%, adj HR=1.46, 95% CI: 1.03-2.09) and patients with a single DES (18.8%, adj HR=1.74, 95% CI: 1.34-2.25, p<0.001) at three years. A stratified analysis by stent type showed a higher risk of the primary outcome in SES with OL (28.7%) compared to other SES groups (without OL: 22.6%, p=0.04; single DES: 17.6%, p<0.001), but not between EES with OL (22.3%) and other EES groups (without OL: 18.5%, p=0.30; single DES: 20.4%, p=0.20).

Conclusions: DES overlap is associated with impaired clinical outcomes during long-term follow-up. Compared with SES, EES provide similar clinical outcomes irrespective of DES overlap status.

Introduction

Stent overlap occurs in up to 30% of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in contemporary clinical practice for a variety of reasons including excessive target lesion length, incomplete lesion coverage, edge dissections and residual thrombus1-4. The use of overlapping bare metal stents (BMS) is associated with inferior clinical outcomes compared to patients treated with a single BMS or overlapping drug-eluting stents (DES), mainly due to higher rates of target lesion revascularisation (TLR)5-7. The marked improvements in angiographic and clinical indices associated with DES in the treatment of single de novo lesions led to a broadening of their indication to include longer and more complex lesions8-12. However, studies assessing clinical outcomes among patients treated with early-generation overlapping DES have yielded mixed results. Among early-generation overlapping DES-treated patients there are clear reductions in the need for repeat revascularisation as compared to patients treated with overlapping BMS, albeit with an increased risk of periprocedural myocardial infarction among patients treated with overlapping paclitaxel-eluting stents (PES)3,7,13. In the largest study to date addressing long-term clinical outcomes among patients treated with the unrestricted use of early-generation overlapping DES, patients with DES overlap had a higher incidence of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (cardiac death, myocardial infarction, ischaemia-driven TLR) and impaired angiographic results as compared with non-overlapping or single DES control groups14. As compared with early-generation devices, newer-generation DES, such as the everolimus-eluting stent (EES), have improved upon the safety and efficacy profile of early-generation devices and are now widely used15-18. Indeed, patients with de novo coronary lesions treated with EES have a significantly reduced risk of MI, ST and repeat revascularisation compared to those treated with early-generation DES and BMS in both short and long-term follow-up19. However, the impact of newer-generation DES on long-term clinical outcomes among patients with DES overlap is unknown. Using data from the prospective, unrestricted LESSON (Long-term comparison of Everolimus-eluting and Sirolimus-eluting Stents for cOronary revascularizatioN) registry20, we sought to compare the long-term clinical outcomes among patients treated with newer (i.e., EES) and earlier-generation DES overlap (i.e., SES) with non-overlapping DES controls stratified according to stent type.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

Patients treated with coronary DES at Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland, were prospectively enrolled into the Bern DES registry. In total, 1,532 consecutive patients were treated with sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) (CYPHERTM; Cordis, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) between May 2004 and January 2006, and 1,601 consecutive patients were treated with EES (XIENCE V®; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA; or PROMUS; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) between November 2006 and March 2009. Patients included in the SIRTAX (Sirolimus-Eluting Versus Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization) trial were not eligible in view of mandated angiographic follow-up. The study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee at Bern University Hospital, Switzerland. Patients gave written informed consent to be followed up prospectively.

DATA COLLECTION

Data were collected as previously described20.The final follow-up was performed between July 2007 and June 2008 in patients who underwent SES implantation, and between June 2009 and March 2010 in patients treated with EES. All baseline clinical and procedural characteristics in addition to follow-up data were entered into a dedicated database, maintained at an academic clinical trials unit (CTU Bern, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland), which is responsible for central data audits and database maintenance.

PROCEDURES

The diameters and lengths of available EES ranged from 2.25 to 4.0 mm and 8 to 28 mm, respectively. SES were available in diameters ranging from 2.25 to 3.5 mm and in lengths from 8 to 33 mm. The patient treatment guidelines, including the periprocedural and post-procedural medication regimen, were carried out according to current best practice guidelines; they did not alter between the inclusion of the first patient into the SES cohort and inclusion of the last patient into the EES cohort. PCI and the use of stents were guided by angiography and in limited cases by intravascular ultrasound during the course of the study period. Balloon predilation was done at the discretion of the operator with a target balloon-to-artery ratio of 1:1. Stents were implanted with the goal of covering the complete lesion. If stent overlap was performed, the operator aimed to achieve an overlapping margin of at least 2 mm. High-pressure balloon post-dilation was performed in cases of incomplete stent expansion or stent overlap. Each patient, regardless of stent type implanted, received a loading dose of clopidogrel 300 mg to 600 mg during or immediately after the procedure and was prescribed aspirin once daily lifelong and clopidogrel for 12 months. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists were used at the discretion of the operator. Creatine kinase (CK), CK-myocardial band (CK-MB), and troponin were assessed regularly at baseline and 12 to 24 hr post PCI, in addition to a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Biomarkers were evaluated every six to eight hours in patients with signs of ischaemia until peak levels were identified.

DEFINITIONS

The primary endpoint comprised death, myocardial infarction (MI), and target vessel revascularisation (TVR) up to a maximum follow-up of three years. The secondary endpoints comprised the single components of the primary endpoint, in addition to cardiac death, target lesion revascularisation (TLR), and definite and definite or probable ST according to Academic Research Consortium criteria21.

Stent overlap was defined as the presence of ≥2 stents within a single treated lesion and an overlapping stent zone of at least 1 mm, as determined by angiography. Cardiac death, Q-wave MI, TVR, TLR and acute coronary syndrome were defined as previously described20.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We performed an analysis of clinical outcomes depending on the presence or absence of stent overlap. Among patients without overlap, we pre-specified two control groups: the first group comprised patients with multiple DES within a vessel without overlap, and the second group comprised patients with a single DES per vessel. Baseline characteristics were compared among the three patient groups or two stent types using chi-square tests for binary variables and analyses of variance for continuous variables. Clinical outcomes were compared among patient groups using full-factorial (patient group x stent type) Cox proportional hazard models (crude analyses). Thereafter, clinical outcomes were compared among patient groups using full-factorial Cox proportional hazard models, weighting each patient with the inverse probability of their actual full-factorial treatment (inverse probability treatment weighting [IPTW], adjusted analyses). All p-values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are two-sided. Analyses were performed using STATA version 12 software (StataCorp, Inc., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

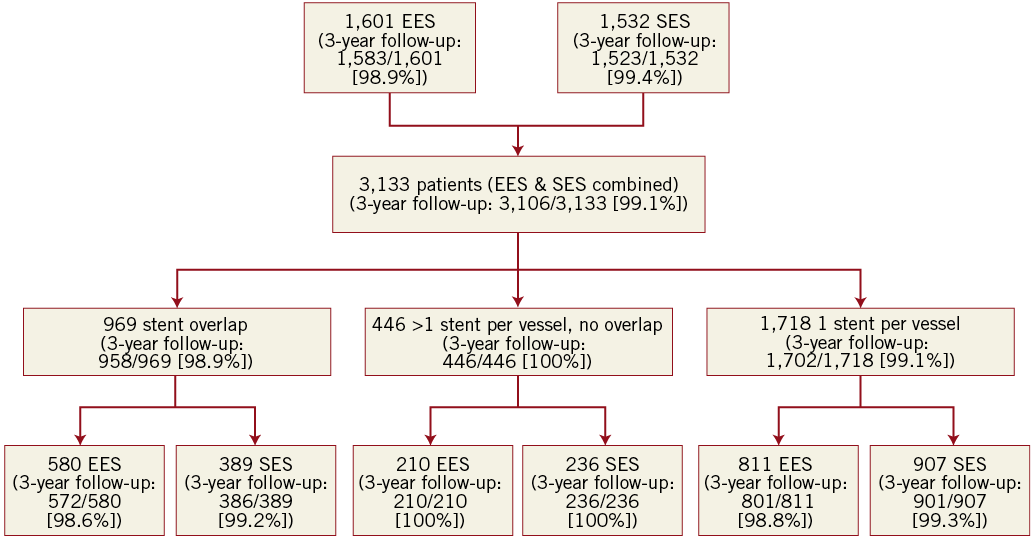

BASELINE CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

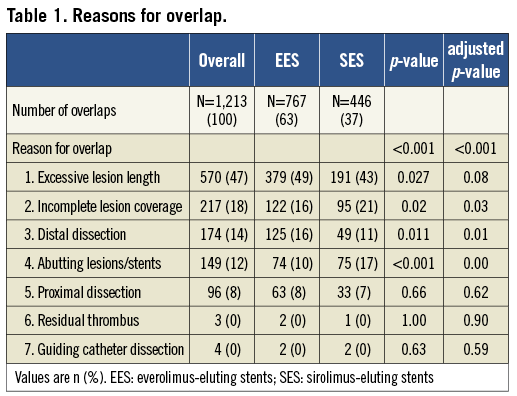

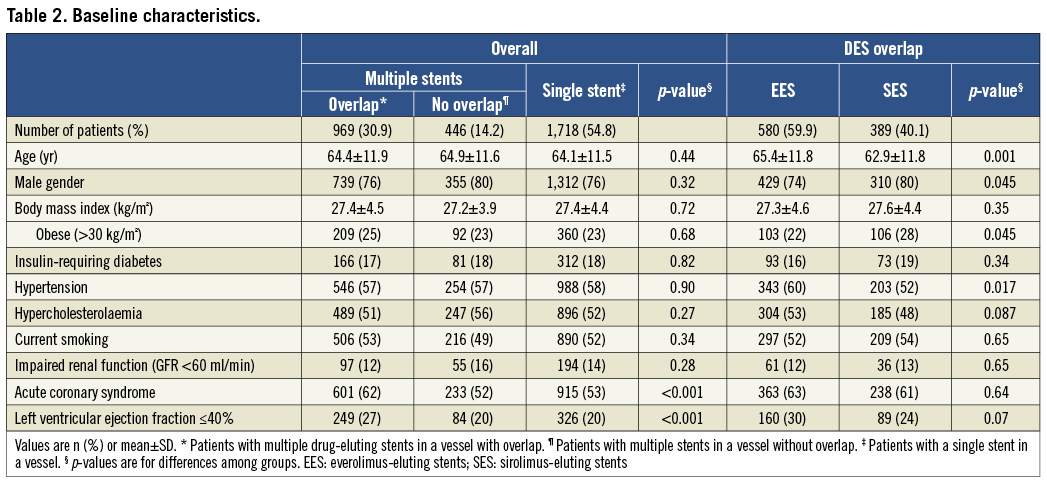

A total of 3,133 patients received treatment with SES (N=1,532) or EES (N=1,601) (Figure 1). The reasons for DES overlap are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences between groups in type of indication with more patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome in the DES overlap group and a lower ejection fraction in the group of patients without overlap (Table 2). Of the 969 patients with DES overlap, 389 patients were treated with SES and 580 patients with EES.

Figure 1. Patient flow chart and rates of successful 3-year clinical follow-up. EES: everolimus-eluting stents; SES: sirolimus-eluting stents

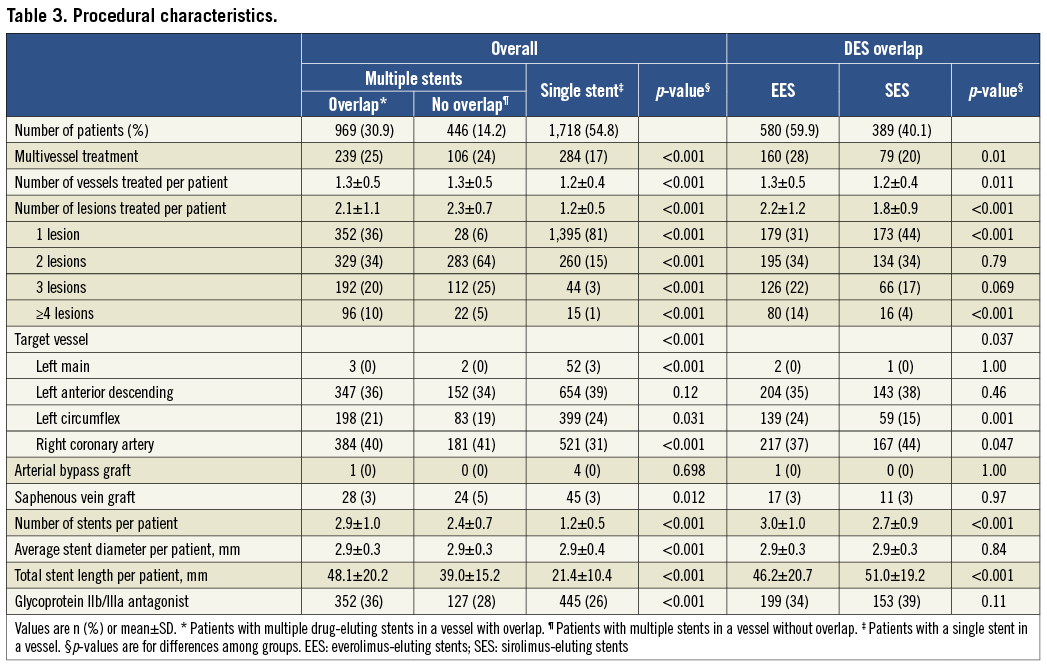

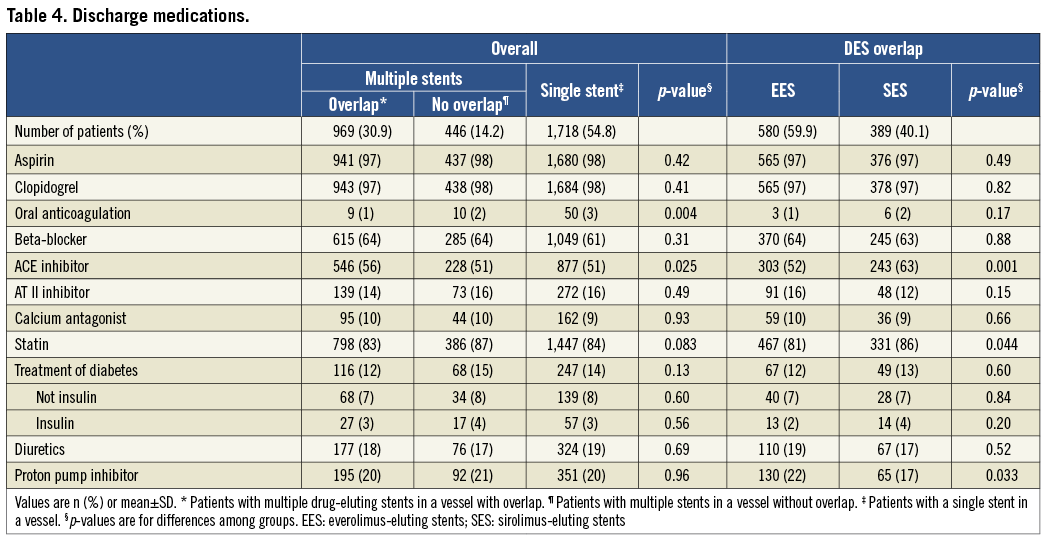

The procedural characteristics are listed in Table 3. When comparing patients with EES and SES overlap, patients with EES overlap appeared to have a greater overall degree of coronary complexity as indicated by more frequent multivessel treatment, more vessels and lesions treated per patient and a greater number of stents implanted per patient. Conversely, patients with SES overlap had a greater total stent length per patient despite having fewer stents implanted.

The medications at the time of discharge are listed in Table 4. There were differences in the use of oral anticoagulation and ACE inhibitors among patients with and without overlap.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

Clinical outcome data were complete for 3,106 (99.1%) patients at three years of follow-up.

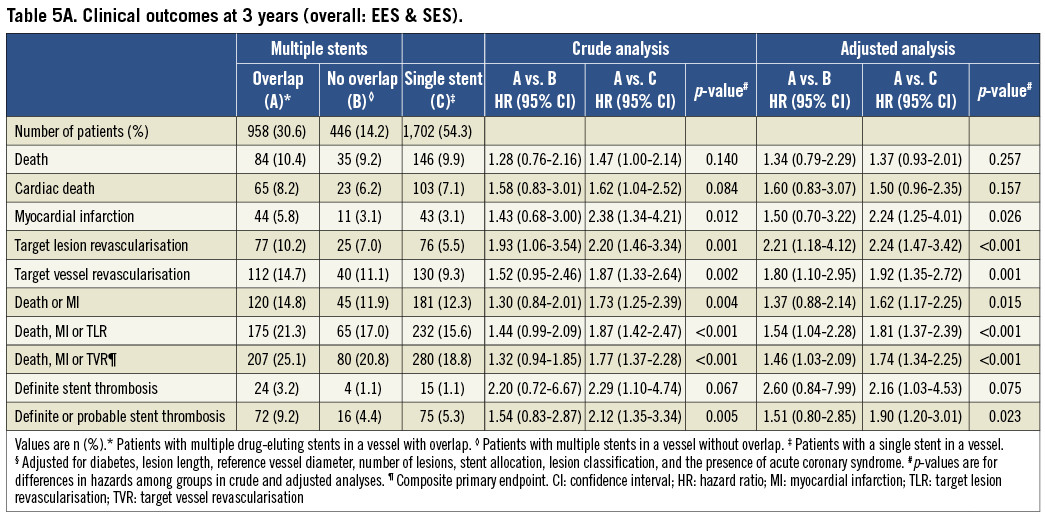

OVERALL (EES & SES COMBINED)

Overall crude and adjusted analyses of adverse events at three years of follow-up are summarised in Table 5A. Compared with controls, patients with DES overlap were more likely to experience the primary endpoint of death, MI or TVR in crude (p<0.001) and adjusted (p<0.001) analyses. The individual hazard ratio (HR) comparing DES overlap with multiple DES in a vessel without overlap was 1.32 in crude (95% CI: 0.94-1.85, p=0.11) and 1.46 in adjusted analyses (95% CI: 1.03-2.09, p=0.04). Similarly, the HR comparing DES overlap patients with a single DES in a vessel was 1.77 in crude (95% CI: 1.37-2.28, p<0.001) and 1.74 in adjusted analyses (95% CI: 1.34-2.25, p<0.001). Differences in rates of the primary endpoint were driven by a higher risk of MI (overlap vs. no overlap: 5.8% vs. 3.1%, adj HR=1.5, 95% CI: 0.70-3.22; overlap vs. single DES: 5.8% vs. 3.1%, adj HR=2.24, 95% CI: 1.25-4.01) and TVR (overlap vs. no overlap: 14.7% vs. 11.1%, adj HR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.10-2.95; overlap vs. single DES: 14.7% vs. 9.3%, adj HR=1.92, 95% CI: 1.35-2.72) compared with both control groups.

DEFINITE STENT THROMBOSIS

Compared with controls there was an overall trend towards higher rates of stent thrombosis in the DES overlap group (24 events [3.2%]) vs. 4 events [1.1%] vs. 15 events [1.1%]) but this did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in crude (p=0.07) or adjusted analyses (p=0.08).

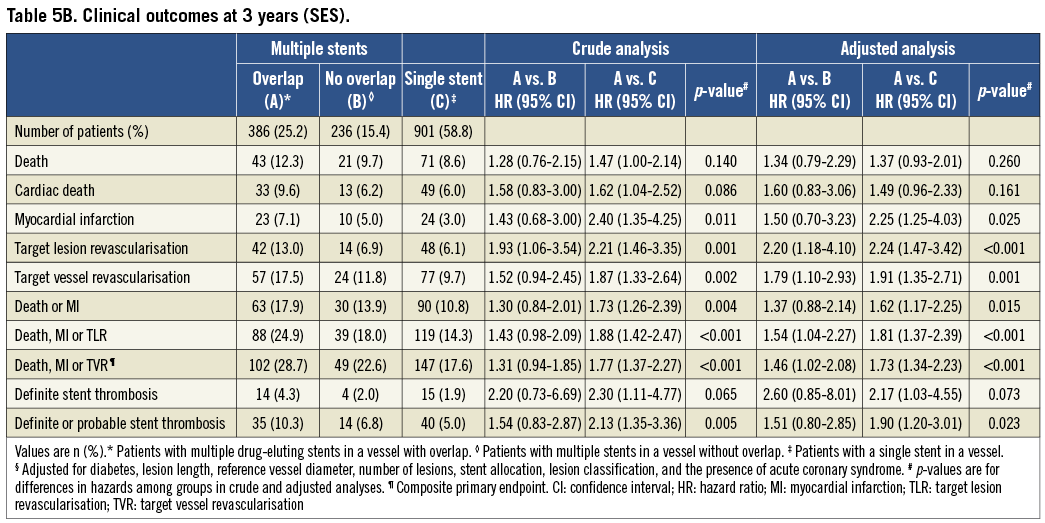

SES OVERLAP

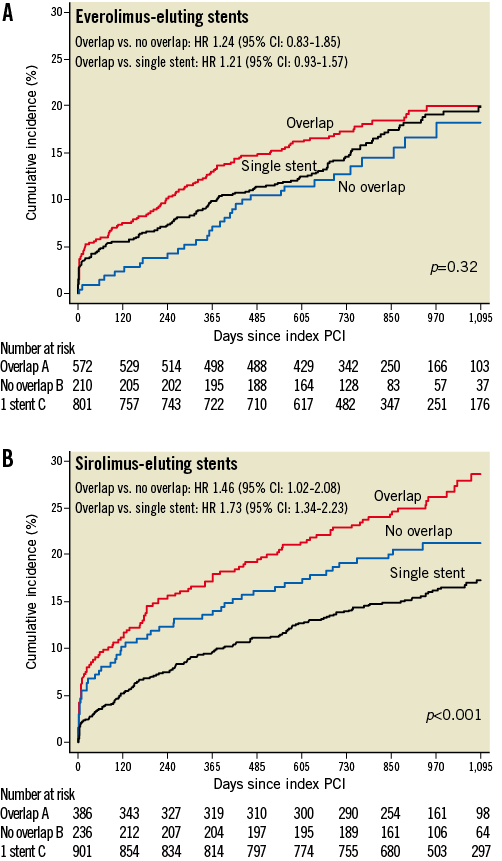

Clinical event rates at three years of follow-up in patients undergoing SES implantation are summarised in Table 5B and Figure 2. Compared with controls, patients with SES overlap were more likely to experience the primary endpoint of death, MI or TVR in crude (p<0.001) and adjusted (p<0.001) analyses. The individual HR comparing SES overlap patients with patients with multiple DES in a vessel without overlap was 1.31 in crude (95% CI: 0.94-1.85, p=0.12), but 1.46 in adjusted analyses (95% CI: 1.02-2.08, p=0.04). Similarly, the HR comparing SES overlap patients with a single SES in a vessel was 1.77 in crude (95% CI: 1.37-2.27, p<0.001) and 1.73 in adjusted analyses (95% CI: 1.34-2.23, p<0.001). The differences were largely driven by TVR (crude and adjusted analyses of TVR: p=0.002 and p=0.001, respectively) and MI (crude and adjusted analyses of MI: p=0.01 and p=0.03, respectively).

DEFINITE STENT THROMBOSIS

Compared with controls there was a trend towards higher rates of stent thrombosis in the SES overlap group (14 events [4.3%]) vs. 4 events [2.0%] vs. 15 events [1.9%]) which did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in crude (p=0.07) or adjusted analyses (p=0.07).

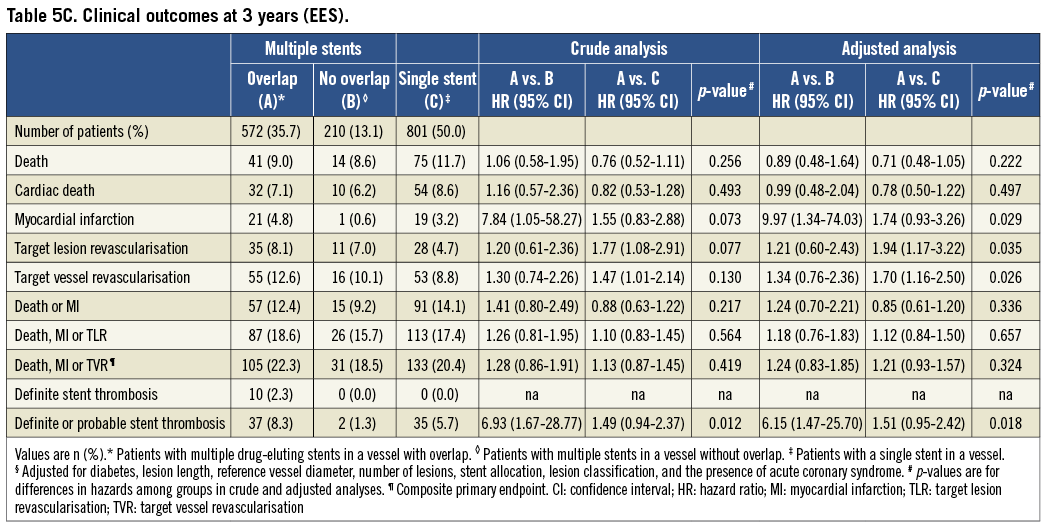

EES OVERLAP

Clinical event rates at three years of follow-up in patients undergoing EES implantation are summarised in Table 5C and Figure 2. There were no significant differences between patients with EES overlap compared with EES controls in the primary endpoint of death, MI or TVR in crude (p=0.42) and adjusted (p=0.32) analyses. The individual HR comparing EES overlap patients with patients with multiple EES in a vessel without overlap was 1.28 in crude (95% CI: 0.86-1.91, p=0.22), and 1.24 in adjusted analyses (95% CI: 0.83-1.85, p=0.30). Similarly, the HR comparing EES overlap patients with a single EES in a vessel was 1.13 in crude (95% CI: 0.87-1.45, p=0.36) and 1.21 in adjusted analyses (95% CI: 0.93-1.57, p=0.16).

Figure 2. Time-to-event curves for the composite primary endpoint. Kaplan-Meier cumulative event curves for the composite primary endpoint (death, myocardial infarction [MI] and target vessel revascularisation [TVR]) through three years among patients treated with everolimus-eluting stents (A) and sirolimus-eluting stents (B). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

DEFINITE STENT THROMBOSIS

Compared with controls there were no significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis in the EES overlap group (10 events [2.3%]) vs. 0 events [0%] vs. 0 events [0%]) in crude (p=ns) or adjusted analyses (p=ns).

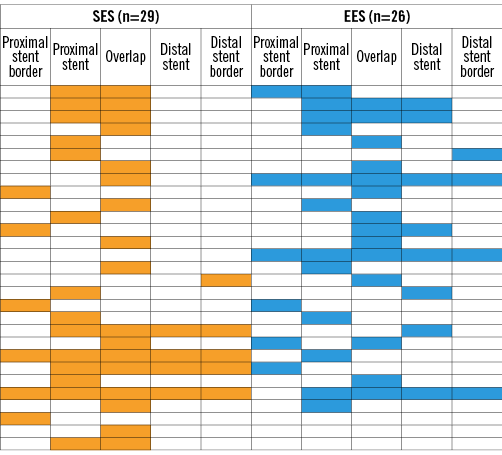

PATTERN OF RESTENOSIS AMONG PATIENTS UNDERGOING TLR

Seventy-seven patients with 77 lesions treated with either SES (n=42) or EES (n=35) overlap underwent TLR during the follow-up period. Angiograms obtained before TLR were available for 67 of the 77 patients. Of the 67 patients, 12 patients underwent TLR for stent thrombosis, of which seven occurred in patients with SES and five occurred in patients with EES. Of the remaining 55 TLR episodes related to in-stent restenosis, 29 occurred in patients with SES and 26 occurred in EES. Figure 3 presents the distribution of restenoses across the different zones of the treated lesions. Of the 55 in-stent restenosis lesions, 36 (65%) lesions were classified as focal, 4 (7%) lesions were classified as multifocal, and the remaining 15 (27%) lesions were classified as diffuse in-stent restenosis.

Figure 3. Pattern of restenosis in patients with overlapping sirolimus (yellow) and everolimus (blue) stents. The lesions of 55 patients with overlapping stents who underwent target lesion revascularisation within the follow-up period are shown. The figure shows a schematic representation of all 55 lesions, and the locations of binary restenosis represented by a yellow-coloured bar (overlapping sirolimus-eluting stents [n=29]) or a blue-coloured bar (overlapping everolimus-eluting stents [n=26]).

Discussion

To date, there are little published data on long-term clinical outcomes following newer-generation overlapping DES implantation. Using data from a prospective, unrestricted DES registry20, we found overall that patients with DES overlap were at an increased risk of the composite endpoint of death, MI and TVR as compared with non-overlapping DES controls during three-year follow-up. However, this finding was driven primarily by a higher incidence of the composite primary endpoint in the early-generation SES overlap patient cohort when compared with non-overlapping SES controls. Conversely, among patients treated with the newer-generation EES, rates of the composite primary endpoint were similar among patients with and without overlap. These findings are clinically relevant for several reasons. First, DES overlap is relatively common in real-world clinical practice. In this unrestricted DES registry, overlap was employed in almost one third of patients undergoing PCI, a figure consistent with previous studies1-4. Second, the increase in adverse long-term clinical outcomes associated with early-generation SES overlap compared with non-overlapping SES controls corroborates our previously published study14 in an entirely separate cohort of patients. The SIRTAX trial was designed to compare the safety and efficacy of the SES and PES22. Using data from this trial we had previously examined the impact of early-generation stent overlap on eight-month angiographic and long-term clinical outcomes and reported higher rates of major adverse cardiac events among patients with DES overlap as compared to controls14. Third, we were able to show that the impairment in long-term clinical outcomes associated with early-generation DES overlap is no longer apparent in patients treated with unrestricted newer-generation EES overlap. The mechanisms underlying the improved long-term clinical outcomes with EES overlap are unclear but may be related to the lower strut thickness resulting in less arterial injury and more rapid and complete endothelialisation, a biocompatible polymer less prone to hypersensitivity reactions, and a lower dose of the antiproliferative drug thereby causing less vascular toxicity at the site of overlap15-20. These improvements may be of particular importance at sites of overlap due to the higher drug and polymer concentration. Potential mechanistic explanations for the association of first-generation DES overlap with impaired clinical outcomes have come from both pathologic (animal and human) and imaging studies23-25. Finn et al, in an animal model comparing early-generation DES overlap with BMS overlap, reported delayed arterial healing, increased inflammation and fibrin deposition at the site of DES overlap23. A human autopsy study demonstrated that both endothelial coverage and a >30% ratio of uncovered struts to total stent struts were powerful histological and morphometric predictors, respectively, of ST24.

These findings may have important clinical implications for patients undergoing PCI who require overlapping DES for various clinical indications, because this study suggests that they are no longer at a higher risk of MACE compared to patients receiving non-overlapping or single stents. The lower risk of ST among EES-treated patients may also have important implications for the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Limitations

First, this study was not a randomised comparison of EES and SES and therefore the findings may have been subjected to bias. Second, there was a sequential enrolment period. However, results were obtained at a single institution and treatment protocols did not change during the enrolment period. Third, systematic angiographic follow-up was not performed. Fourth, the selection of control patients is inherently related to prognosis. Similar to our previous overlap study, we opted for comparing patients with stent overlap with two different groups: one group of patients with multiple DES within a vessel but no overlap and one group with implantation of a single DES only within a vessel. We present results from both unadjusted analyses and analyses adjusted for the most important confounding factors to ensure full transparency. Additionally, we compared earlier and newer-generation overlapping DES with controls from within their respective stent generational group rather than a direct comparison of overlapping SES versus overlapping EES to minimise any intergenerational bias. Finally, the SYNTAX score was not prospectively calculated in patients included in this registry and therefore worse clinical outcomes among patients with SES overlap might be related to underlying coronary complexity. However, based on indirect markers of coronary complexity, it appears that patients undergoing EES overlap had a higher degree of coronary complexity, yet there remained no significant differences in clinical outcomes between EES overlapping and non-overlapping groups.

Conclusions

DES overlap is associated with impaired clinical outcomes during long-term follow-up. Compared with early-generation SES, newer-generation EES appear to overcome this limitation and provide similar clinical outcomes irrespective of DES overlap status.

Conflict of interest statement

C. J. O’Sullivan is the recipient of a research grant from the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. G. G. Stefanini is the recipient of a research fellowship (SPUM) funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 33CM30-140336). M. Taniwaki is the recipient of a research grant from Abbott Vascular, Japan, and OrbusNeich. B. Meier has received educational and research support from Abbott, Cordis, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic, and has received consulting and lecture fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, and Medtronic. S. Windecker has received research grants from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Biosensors, Cordis, Medtronic and St. Jude. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.