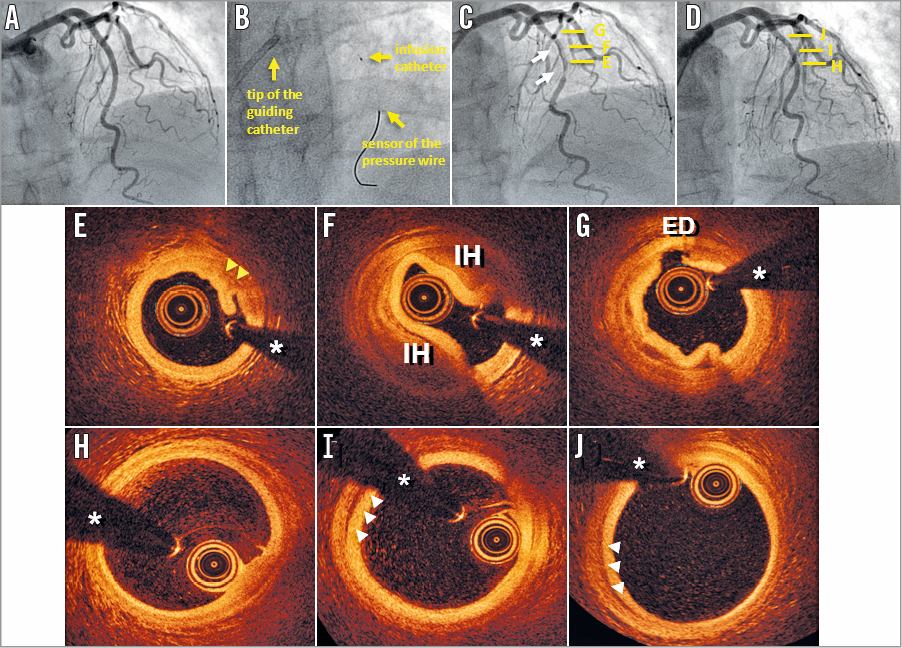

* denotes wire artefact

A 65-year-old woman with a previous history of hypertension was referred to our institution due to effort angina with a positive exercise stress test. Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries (Panel A). A vasospasm provocation test with methyl-ergonovine was negative. With the aim of assessing the state of the microvasculature, absolute coronary blood flow measurement by thermodilution was performed as previously described1-3. First, a pressure wire (Certus™; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) was progressed across the mid segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) without any difficulties. Then, a 2.52 Fr multipurpose infusion catheter (RayFlow®; Hexacath, Paris, France) was advanced to the proximal-mid LAD (Panel B). Finally, continuous infusion of saline was initiated and absolute coronary blood flow was calculated. Unexpectedly, a clear angiographic haziness, with lumen narrowing, was detected at this site in the control angiogram (Panel C, white arrows). To clarify this image better, optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed, revealing striking images, highly suggestive of localised but severe vasospasm. These images showed: 1) a thickened media and corrugated intima layer (yellow arrows) associated with lumen narrowing at the distal segment (Panel E), 2) a middle region depicting an intramural haematoma (IH) (Panel F), and 3) an entry door (ED) of a confined intimomedial dissection at the most proximal segment (Panel G). After intracoronary nitroglycerine administration, lumen narrowing readily resolved, with only mild lumen haziness persisting at the mid LAD. To elucidate a potential reason for this unexpected complication, the saline infusion pump was reviewed. This disclosed that, due to a technical mistake, the infusion flow rate was programmed at 120 ml/min (recommended rate ≤30 ml/min) with a maximum pressure limit of 600 pounds-force per square inch. Although the patient remained asymptomatic, she was eventually admitted for clinical observation. A control coronary angiography at 48 hours confirmed complete resolution of the angiographic abnormalities (Panel D). OCT at the most distal portion of the LAD showed an almost normal aspect (Panel H). However, at more proximal segments, OCT disclosed a very small residual IH with normal vessel lumen (Panel I, Panel J, white arrowheads). Cardiac biomarkers were negative and the patient was discharged uneventfully. At three-month follow-up she remains asymptomatic.

This case nicely illustrates that, when new invasive methods are introduced for the first time in the catheterisation laboratory, major attention to subtle details remains crucial in order to prevent potential complications. In our patient, high-pressure jets emerging from the side holes of the infusion catheter (as a result of the erroneous flow programming) probably induced an iatrogenic intimal tear and IH leading to severe associated vasospasm that, fortunately, resolved with conservative management. Furthermore, in this case OCT was instrumental in guiding the clinical decision-making process in our patient.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.