CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 50-year-old male with diagnosis of acute type A aortic dissection underwent surgical repair. Immediately after surgery the patient had transient ECG changes, a raise in serum cardiac markers and physical signs of heart failure.

INVESTIGATION: Physical examination, electrocardiography, echocardiography (transthoracic and transoesophageal), coronary angiography, intravascular ultrasound.

DIAGNOSIS: Type A aortic dissection.

MANAGEMENT: Surgical repair, coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention.

KEYWORDS: Aortic diseases, aortic dissection, blood vessel prosthesis implantation, coronary angiography, coronary diseases, angioplasty, transluminal, percutaneous coronary stents

Presentation of the case

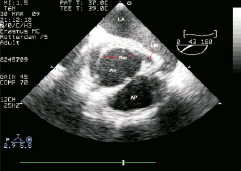

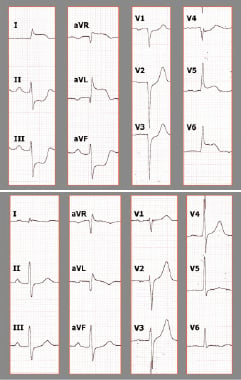

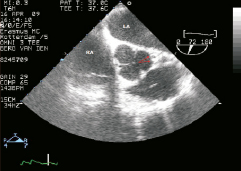

We present the case of a 50-year-old male, who had a background history of hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and peripheral vascular disease and a family history which included the death of a brother from an aortic dissection. He presented with sudden onset of chest pain, which radiated to the back and both shoulders, there was no dyspnoea or syncope. On admission to the emergency room, a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) indicated the presence of an intimomedial flap in the aortic root involving the supra-coronary portion and extending into the left main coronary artery (LM) (Figure 1, Moving image 1). The left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) was preserved, but there was severe anterior and lateral hypokinesia (Moving image 2). Following the diagnosis of Type A aortic dissection he underwent emergency surgical reconstruction of the proximal ascending aorta using a woven polyester graft Vascutek Gelweave Ante-flo nr. 26 (Terumo Cardiovascular Systems Corporation, Ann Arbor MI, USA) which extended from the supra-coronary portion, until the take-off of the right brachiocephalic trunk. On visual inspection both coronary ostia appeared free from dissection, however the aortic wall in the proximity of the right coronary artery (RCA) ostium appeared dissected, which was treated with surgical glue. Immediately after surgery, there was transient ST elevation in leads I, aVL, V5-V6, and ST depression in the inferior leads, together with changes in the electric axis (Figure 2). Twenty minutes later, the ST segment returned to baseline. Laboratory tests showed a haemoglobin of 6.6mmol/l (10.6 g/dl), and raised serum markers of myocardial damage (peak CK-MB 308 µg/l, peak TnI 14.4 µg/l).

Figure 1. Transoesophageal echocardiogram, plane of the aortic root at the level of left main ostium. Notice the dissecting flap, apparently extending into the left main coronary artery. LA: left atrium; Ao: aorta; AP: arteria pulmonaris; LM: left main

Figure 2. ECG recordings immediately after emergent surgery (A): ST elevation in I, aVR, aVL, V5-V6 is clearly recognisable, as well as ST depression in the inferior wall. All ST changes had normalised 20 minutes later (B).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How could I treat?

The Invited Expert’s opinion

In this case, the presentation of a patient treated for a (type A) dissection of the ascending aorta, two specific elements in the pre-operative assessment were stand out: the relative young age of the patient and the family history (in first-degree) of death related to a dissection of the aorta. An inherited disorder of the connective tissue (Marfan’s syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV) should be suspect.1 In these patient populations a cautious approach to the use of valve-sparing aortic root replacement surgery should be advocated!

Immediately following aortic root surgery, the patient developed new (transient) signs of myocardial ischaemia on the postoperative 12-lead ECG. The patient developed raised serum markers of myocardial damage and a new q in lead 1 and aVL. These findings are consistent with a perioperative myocardial infarction.

The high ST segment elevation in lead aVR points to a transmural ischaemia of the basal part of the septum through disturbance of a major septal branch blood flow (injury current directed toward the right shoulder) –that is, interruption of LAD blood flow, and may be considered an important predictor of acute LMCA (left main coronary artery) obstruction.2-5 The ST-segment elevation in leads aVL and I, V5-6 and the reciprocal ST segment depression in the inferior (II, III, aVf) leads may go along with this finding.6,7 Given the preoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) findings that indicated a potential extension of the intimomedial flap into the LMCA (Figure 1), and the valve-sparing surgical technique used, a residual dissection of this segment should be feared. This is a potential life-threatening condition –watchful waiting is not an option in this patient. Detailed (non-invasive!) imaging of the aorta and coronary tree –focussing on the LMCA– is mandatory. The differential diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome, due to rupture of a vulnerable coronary plaque, and perioperative coronary (air) embolism is less obvious, but should be taken into consideration.

The choice of the initial imaging modality often reflects availability rather than preference. In this event I would advise combining TEE and computed tomography (CT). TEE is accurate and can be performed quickly at the bedside with minimal risk, it will provide essential information on function and morphology of the aortic valve. CT should provide detailed imaging of the aorta and coronary tree and is required while considering early surgical reintervention.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

How could I treat?

The Invited Expert’s opinion

This is a patient who was operated on an emergency basis due to an acute aortic dissection. At surgery a rather classical ascending aortic dissection was observed, with a detachment of the intima at the level of the right coronary sinus of Valsalva implicating part of the right coronary ostium. After application of fibrin glue at this level to ensure no further dissection, and an adequate lumen of the coronary orifice, the surgeons proceeded to the implantation of a straight dacron tube from just distal of the sinotubular junction to the beginning of the aortic arch, the patient was satisfactorily weaned off extra corporal circulation and sent to the ICU. Haemodynamically stable for the first hours, he suddenly developed changes on the ECG with ST elevation in aVR and significant depression in the diaphragmatic leads. Those changes, although disappearing some time later, were followed by a moderate increase of troponin levels.

What to do? After this type of operation one possibility to explain these changes is an air embolism into the RCA. A bit late, perhaps, after surgery, but it may be due to the first mobilisation of the patient for physio, which displaced air bubbles from the LV through the aortic valve into the right artery. If these changes do not repeat themselves this could well explain the event. However, most commonly, when things may go wrong, they go wrong and we could have a further episode of the same characteristics. In this case, immediate transesophageal echo should be performed to visualise the aortic root. In the case echo is not able to give an adequate explanation, a different imaging tool would be required. AngioCT scan or angiography could well show a re-detachment of the intima, the most typical surgical complication at this level in this type of patient. The intima may be again dissected and induce an occasional occlusion of the RCA ostium and even, for further extension, of the left main. In fact, changes at avR may well be due to intermittent obstruction of the left artery.

Should the signs of an intimal flap be observed, a decision for surgical re-exploration has to be adopted without delay to re-attach the intima to the aortic wall, something often difficult to achieve, complex, as it may be to properly accomplish a Bentall procedure due to the fact that the friability of the tissue at the level of the buttons may become a serious and even lethal technical problem. CABG to the epicardial coronary arteries may be the only resource after occlusion of the proximal end.

Time is crucial to avoid irreversible myocardial damage of the left ventricle, which already had an insult during the first procedure. In consequence, decisions have to be taken promptly.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

Actual treatment and management of the case

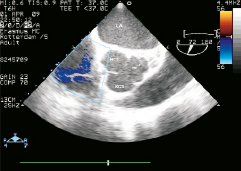

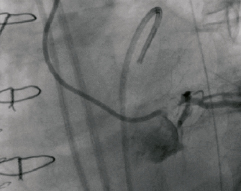

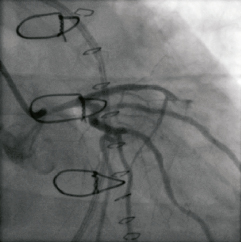

Post-operative recovery was hampered by the development of refractory heart failure which prevented extubation, hypotension which required inotropic support, and progressive deterioration in renal function. A repeat TEE showed severely depressed LV systolic function, with anterior and lateral akinesia (Moving image 3). Furthermore, a marked tethering phenomenon was inducing moderate mitral regurgitation (MR), and within the aortic root a small flap was clearly visible in the left coronary sinus (Figure 3, Moving image 4). On the 7th day post-surgery the patient become electrically unstable, requiring repeated external defibrillation, as well as hypotensive (blood pressure 80/40 mmHg) resistant to inotropic support. At this point a senior interventional cardiologist (PWS) became involved in the patient’s management and emergency coronary angiography was performed. In view of the recent aortic dissection, the surgeons advised against using the femoral arteries for vascular access and therefore the right radial artery was used. Initially during diagnostic angiography the ostium of the LM was not found, but following a forceful injection of contrast, a transient opening of the LM was observed, followed by a quick re-closure (Figures 4 and 5, Moving image 5 and 6). This finding suggested that the dissection flap had extended into the LM.

Figure 3. Transesophageal echocardiogram, plane at the level of the aortic valve. Notice the image suggesting the presence of an extension of the intimomedial flap in the left coronary sinus of Valsalva. LA: left atrium; NCS: non-coronary sinus; RCS: right coronary sinus

Figure 4. Left anterior oblique (LAO) projection. Forceful injection of contrast through a 5 Fr diagnostic JL catheter at the moment of the transient opening of the dissected left main.

Figure 5. Caudal right anterior oblique (caudal RAO) projection after forceful injection of contrast: Notice the severe narrowing of the left main, and the incomplete opacification of the left anterior descending (LAD). Indeed, the video shows a slower rather than incomplete opacification of the LAD.

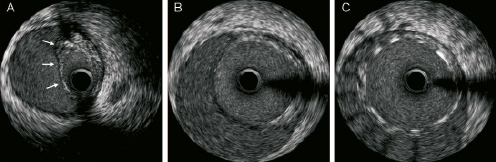

Figure 6. Mechanical IVUS pullback, after stenting of the left main (LM): the most distal frames (a), corresponding to mid and proximal LAD, still show a flap collapsing the true lumen at this level (arrows), whereas in the LM (b & c) the stent keeps the patency of the true lumen. Notice that the stent does not contact the dilated adventitia (c), resembling malapposed.

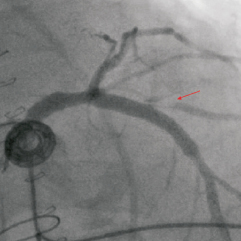

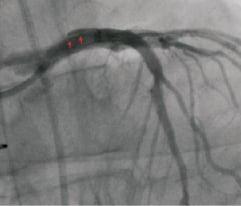

The patient was haemodynamically unstable, and therefore as the first step a 4.5×12 mm TAXUS Liberté stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was implanted into the LM. Post-stenting, mechanical intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) demonstrated a patent true lumen within the LM, and an extension of the dissection flap into the mid and proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Figure 6). It can be noticed here that the stent does not contact the dilated adventitia, but the intimo-medial flap (Figure 6C), seemingly malapposed. The LAD was stented with a Taxus Liberté 4.5×32 mm, and subsequent angiography demonstrated a patent LAD however, the dissection was now observed to extend into the 1st diagonal (Figure 7, Moving image 7). A Xience V 2.5×15 mm (ABBOTT Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was implanted in the diagonal, followed by final kissing balloon dilatation of the LAD-diagonal bifurcation.

Figure 7. Cranial anteroposterior (cranial AP) projection after stenting of the LM and proximal LAD. Notice how the ostium of the 1st diagonal branch appears clearly dissected (arrow).

In view of the findings on IVUS, the concern about an eventual stent malapposition in the LM stent led to post-dilatation with a non-compliant 6×15 mm balloon. Unfortunately, this resulted in rupture of the intimomedial flap within the LM (Figure 8, Moving image 8), opening a new wide communication between the true and false lumens. Contrast injected into the true lumen stained the coronary false lumen and the left coronary sinus of Valsalva. This complication was treated by placing a 4×16 mm covered stent (Jostent Graftmaster) in the LM. There was a good final angiographic result, and the stents within the LM were clearly identified on a post-procedural TEE (Figure 9). The blood pressure at the end of the procedure was 110/70 mmHg.

Figure 8. Cranial anteroposterior (cranial AP) projection after balloon post-dilation of the left main (LM) ostium. Reappearance of a new flap in the LM (arrows), and the reflow of the injected contrast into the aorta led to the suspicion of rupture of the intimomedial flap.

Figure 9. Transesophageal echocardiogram, plane at the level of the aortic valve and coronary ostia. The stented left main ostium can be discerned in the image (arrows). LA: left atrium; RA: right atrium

Over the course of the next few days increasingly severe aortic regurgitation was detected, which was presumed to be due to progression of the dissection into the right coronary sinus, such that it was affecting the cusps of the aortic valve. The patient underwent a further operation, and a Bentall tube replaced the aortic valve.

Discussion

Coronary mal-perfusion, which is a complication in 6.1% of TypeA acute aortic syndromes1, affects the RCA more commonly than the LM, in a ratio 4:1. Our case presents this infrequent complication, albeit already reported in the literature2. It is remarkable, however, that despite an upfront suspicion, and a thorough inspection of the aortic root during surgery, no involvement of the coronary ostia was identified. Nonetheless, soon after surgery, both electrocardigraphic and echocardiographic signs raised once again the suspicion of dissection of the LM. The fact that the aortic wall had been glued in the proximity of RCA, could initially have confused the physicians, and led them to suspect that the RCA was the cause of the patient’s instability post-operation. It is an interesting matter of discussion as to which diagnostic attitude should have been adopted at this point.

An aggressive approach could be advocated on the basis of the transient ECG changes, perfectly matching the segmental abnormalities in the contractility, and the pathologic image seen in the left coronary sinus of Valsalva on TEE, which is highly suggestive of the presence of a dissection flap at this point. This evidence could be considered enough to justify an aggressive and early intervention, given that the suspected complication could be potentially life-threatening. On the other hand, transient ischaemic ECG changes are commonly seen in the recovery of such patients because the intervention itself can jeopardise the myocardium. This is most notable when the patient is haemodynamically unstable, or if severe post-operative anaemia is present. Therefore, an initially conservative attitude seems also reasonable, provided that the progress of the patient can be closely monitored. This was the initial choice in this patient, until his clinical deterioration confirmed the suspicions. A third option, which sits midway between an aggressive and conservative approach, can be also considered: to perform a complementary non-invasive cardiac imaging study, other than the already performed TEE. Both cardiac magnetic resonance and multislice CT (MSCT) claim to be useful in coronary diagnosis. Furthermore, there are some case reports of MSCT in this specific scenario, detecting the extension of the dissecting flap into the RCA3. Diagnosis of LM occlusion by MSCT has been also reported in the literature4. The critical condition of the patient is an additional argument favouring the use of MSCT. It could have solved the question as to whether the LM was affected either by the dissection flap or by primary atherosclerotic disease, confirmed the diagnosis, and permitted a safer and quicker management of the patient.

Once coronary angiography had diagnosed the extension of the dissection flap into the LM, there were only two possible therapeutic options: stenting or surgical reintervention. In this critical situation with an unstable patient, stenting is most likely to be able to promptly treat the acute complication, and to stabilise the patient. Therefore we did not hesitate to opt for stenting, even though it could be argued that the procedure was considerably risky, and that the full extent of the dissection flap could not have been properly assessed, as the subsequent events would later confirm.

The IVUS images obtained after the deployment of the first stent in the LM are very illustrative of one of the lessons learned from this case. When coronary dissection occurs, the arterial media splits and the elastic adventitia is exposed to the arterial pressure, causing the adventitial layer to dilate disproportionately. IVUS shows how the stent placed in the LM is adequately expanded, well apposed to the intimomedial flap, but far away from the adventitial layer, thus falsely resembling malapposition. This is not a trivial issue, because stent malapposition is a known predisposing factor for stent thrombosis5,6, and this complication can be fatal when it occurs in the LM. There are technical limitations which reduce the accuracy of IVUS when assessing the stent apposition to the intimomedial flap. The artefacts induced by the stent, and the unpredictable acoustic impedance of the flap, make the interpretation of the images very difficult. In the near future it might be more appropriate to use other invasive imaging techniques like optical coherence tomography (OCT), which has a much higher resolution and better definition than IVUS. In our patient, the justifiable concern to avoid an eventual stent malapposition in the LM led to an excessive post-stent dilatation, which ultimately ended up by rupturing the flap.

At this point injection of contrast into the true lumen of the LM stained the left coronary sinus. Dissection of the sinus of Valsalva may appear as a complication of diagnostic or therapeutic cardiac catheterisation, and may be self-limited or life-threatening. Most of the reported cases affect the right coronary artery and its sinus7-13, and are satisfactorily solved by stenting the coronary artery or by conservative treatment7-9,11-13. MSCT7 or TEE11 have been employed to monitor the progress in these cases. When the dissection affects the LM, and its corresponding sinus, several cases have reported extensive aortic dissection, requiring surgical correction14,15. We cannot infer any valid conclusion from a collection of case reports, and moreover, in our patient, the staining of the sinus of Valsalva might not indicate iatrogenic dissection, given that an aortic flap existed primarily. Nevertheless, the patient’s progress confirmed the need for surgical intervention, because the un-sealed flap gradually destroyed the functional structure of the aortic valve, leading to severe aortic regurgitation. Regardless of these considerations, percutaneous intervention was performed and enabled the patient to overcome a life-threatening situation, but also to survive to have further surgical reintervention.

References

Online data supplement

Moving image 1. Transoesophageal echocardiogram, plane of the aortic root at the level of left main ostium. Notice the dissecting flap, apparently extending into the left main coronary artery.

Moving image 2. Transoesophageal echocardiogram: trans-gastric short axis view of the left ventricle, showing preserved global ejection fraction, with severe anterior and lateral hypokinesia.

Moving image 3. Transoesophageal echocardiogram: trans-gastric short axis view of the left ventricle, showing severely depressed ejection fraction, with anterior and lateral akinesia.

Moving image 4. Transesophageal echocardiogram, plane at the level of the aortic valve. Notice the image suggesting the presence of an extension of the intimomedial flap in the left coronary sinus of Valsalva.

Moving image 5. Left anterior oblique (LAO) projection. Forceful injection of contrast through a 5 Fr diagnostic JL catheter at the moment of the transient opening of the dissected left main.

Moving image 6. Caudal right anterior oblique (caudal RAO) projection after forceful injection of contrast: Notice the severe narrowing of the left main, and the incomplete opacification of the left anterior descending (LAD). Indeed, the video shows a slower rather than incomplete opacification of the LAD.

Moving image 7. Cranial anteroposterior (cranial AP) projection after stenting of the LM and proximal LAD. Notice how the ostium of the 1st diagonal branch appears clearly dissected.

Moving image 8. Cranial anteroposterior (cranial AP) projection after balloon post-dilation of the left main (LM) ostium. Reappearance of a new flap in the LM, and the reflow of the injected contrast into the aorta led to the suspicion of rupture of the intimomedial flap.