CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: An 84-year-old male with previous history of multiple surgical and percutaneous coronary revascularisations presented with unstable angina.

INVESTIGATION: Coronary angiogram, ECG, echocardiogram.

DIAGNOSIS: Severe three-vessel disease with only one graft patent. This graft is a right internal mammary artery connected to a radial graft and to a marginal. In-stent restenosis in the radial graft anastomosis to the marginal. Left ventricle dysfunction.

MANAGEMENT: Coronary revascularisation with a triaxial “grandmother, mother and child” system.

KEYWORDS: coronary revascularisation, in-stent restenosis, mother and child

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

An 84-year-old male with multivessel coronary artery disease and permanent atrial fibrillation (AF) on anticoagulation, also with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia, presented with unstable angina. He had an extensive history of coronary intervention including the following. 1) 1983 – coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) with saphenous vein graft (SVG) to the left anterior descending (LAD), the left circumflex (LCx) and the posterior descending arteries (PDA) for acute inferoposterior myocardial infarction (MI). 2) 1989 – repeat CABG for angina (previous grafts occluded) with left internal mammary artery (LIMA) to LAD, SVG to first obtuse marginal (OM1) and PDA. 3) 2002 – percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of saphenous graft to OM1 with two stents after presenting with unstable angina with diffuse native vessel disease and blocked grafts. 4) 2003 – CABG with right internal mammary artery (RIMA) extended with a radial graft to the OM1 for ongoing angina. 5) 2014 – admitted with angina (CCS grade III-IV). Angiography revealed severe stenosis of the RIMA radial graft to OM1 anastomosis. After a failed attempt at percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) via the right femoral route (144 cm standard PTCA balloons could not reach the target lesion with a 90 cm guiding catheter), a 2.5×18 mm Resolute stent (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was successfully implanted in the OM1, via the right brachial artery approach in a second attempt two days later. A 7 Fr internal mammary (IM) catheter, shortened by approximately 30 cm, was placed at the ostium of the RIMA and through it a 6 Fr GuideLiner® V3 catheter (Vascular Solutions, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was advanced into the RIMA followed by successful delivery of a 1.5×15 mm Sprinter® Legend balloon (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and a Resolute drug-eluting stent (Medtronic). 6) June 2015 – admitted with unstable angina. Angiogram showed in-stent restenosis (ISR) in the graft anastomosis to the OM1 which was successfully treated with simple balloon angioplasty after unsuccessfully attempting drug-eluting balloon (DEB) delivery (the same technical strategy of a shortened 7 Fr IM catheter plus a 6 Fr GuideLiner V3 was used).

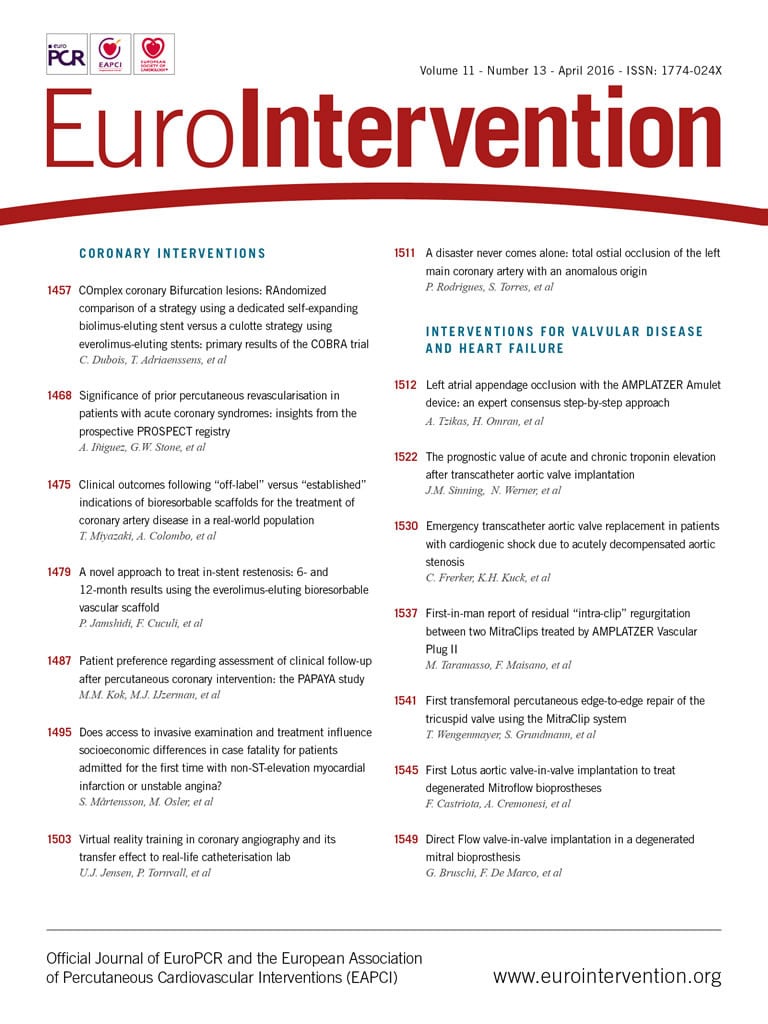

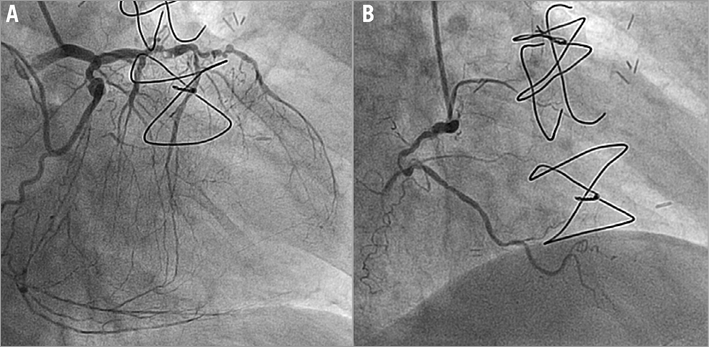

His current admission in August 2015 was for resting chest pain of 10 days duration which persisted in spite of nitrate infusion. The patient was asymptomatic in the intervening period between recurrences of coronary stenoses. ECG showed rate-controlled AF with no new evidence of ischaemia and normal cardiac biomarkers. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an EF of 35% with an apicoanterior aneurysm and an akinetic inferoposterior wall. There was preserved contractility in other segments with a mildly dilated left ventricle (end-diastolic volume 141 ml). An angiogram revealed that the LAD was diffusely diseased with 80% stenosis in the proximal and mid segments. The distal LAD showed chronic occlusion with retrograde filling from right coronary artery (RCA) collaterals, Rentrop II. The first diagonal (D1) was a small vessel with severe ostial stenosis (80%) and diffuse disease. The LCx revealed 80% stenosis in the proximal third and the OM1 had ostial occlusion (Figure 1A). The RCA showed 100% occlusion in the mid segment (Figure 1B) with retrograde filling from the septal branches (Figure 1A). The RIMA-radial graft, in turn, was observed to have 80% ISR in the radial graft anastomosis to the OM1, albeit with TIMI 3 flow (thus becoming the only vessel with good flow in spite of ISR) (Figure 2, Moving image 1, Moving image 2). His medications included dual antiplatelet therapy, an anticoagulant, two antianginals (calcium channel blocker and ranolazine intolerance), ACEI, two lipid-lowering agents and insulin.

Figure 1. Angiogram of native left (A) and right (B) coronary arteries.

Figure 2. Angiogram of right internal mammary artery extended with a radial artery graft (A) and radial graft anastomosis to obtuse marginal and DES in-stent restenosis (B).

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

The authors report an interesting case of recurrent in-stent restenosis (ISR) at an arterial graft anastomosis with an obtuse marginal branch in a patient with prior surgical and percutaneous coronary revascularisations. The case is complex for two key reasons: first, because of the clinical complexity of an elderly patient with multiple comorbidities and an aggressive coronary artery disease, who has already been treated three times with coronary artery bypass grafting, and second, because of the procedural technical challenges related to the complex access to the diseased segment.

In view of the patient’s clinical history, the subocclusive ISR within the drug-eluting stent (DES) previously implanted at the site of the graft anastomosis should be considered the culprit lesion of the unstable angina episode. Therefore, we would plan a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the graft anastomosis. We would select a right brachial access –this was successful on the occasion of the previous two PCIs– a short or manually shortened 6 Fr soft-tip internal mammary catheter, and a guide extension catheter. Prior to attempting any balloon dilatations, we would perform intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging with the aim of clarifying the mechanisms underlying ISR (i.e., to exclude a possible mechanical aetiology). In case of evidence of DES malapposition or underexpansion, we would perform a high-pressure dilatation with a non-compliant balloon, size based on the IVUS findings. In case of the absence of a mechanical ISR aetiology, we would dilate the lesion with a scoring balloon based on recent evidence of the superior angiographic effectiveness of scoring balloon compared with standard balloon alone predilation in the setting of ISR1. After predilatation, we would proceed to the implantation of a new-generation ultrathin-strut limus-eluting stent, which has recently been shown to provide the best angiographic and clinical effectiveness in ISR lesions2. Post-dilatation of the implanted DES with a non-compliant balloon would complete the PCI procedure, followed by an IVUS control of the result.

In addition to the ISR treatment, we would also consider performing a PCI of the proximal LAD and the first diagonal branch. Based on the information provided by the authors, the arterial graft to the LAD was known to be blocked since 2002. In view of an apicoanterior aneurysm shown by the transthoracic echocardiogram, we would not consider a revascularisation of the distal LAD. Conversely, improving the perfusion of the large second septal branch and of the first diagonal branch might be of clinical benefit for this patient.

Finally, in view of the coexisting permanent atrial fibrillation, we would discharge the patient on triple antithrombotic therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel and oral anticoagulation), with the recommendation to discontinue clopidogrel after one month3.

Conflict of interest statement

G. Stefanini received speaker/consultant fees from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, B. Braun, Biotronik and The Medicines Company. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

The treatment of patients presenting with “recurrent” in-stent restenosis (ISR) is always a challenge, as the long-term clinical and angiographic results of these “frequent flyers” can never be guaranteed3,4. This conceptual concern may occasionally be aggravated by technical considerations which pose additional difficulties in obtaining satisfactory acute results. All of these issues should be addressed in the case presented by Herrera-Nogueira et al. First of all, the technical difficulties associated with this very distal lesion should be overcome in order to optimise acute results. Second, if possible, the underlying substrate accounting for the recurrent episodes of focal ISR should be unravelled4. Finally, a “best-in-class” therapeutic strategy should be selected to tackle this vexing problem definitively3,4.

Before focusing on the culprit lesion, achieving a complete revascularisation might benefit this patient with severe systolic dysfunction. However, an attempt to revascularise the occluded right coronary artery could only be justified if myocardial viability is demonstrated in the currently akinetic inferior wall. Should this be contemplated, a retrograde approach, although very challenging, might be more attractive considering the large septal branches, even if previous treatment of the proximal lesion on the left anterior descending coronary artery is needed.

Regarding the long and winding “right-mammary-radial-artery road”, the authors previously solved the difficulties by selecting a brachial access, cutting the guiding catheter and using the extension of a GuideLiner V3 catheter (Vascular Solutions) to reach the lesion. The lengths of guiding catheters, balloons and stents from different companies are slightly different, and some extra long material is available. This should be checked in order to select an appropriate combination. Although using the same strategy which proved successful in the previous procedure may not appear too elegant, this remains practical and efficacious. Alternatively, we would discard the possibility of opening the occlusion of the marginal branch anterogradely, via the native circumflex coronary artery, as this patient has had surgery on this vessel on three previous occasions.

The second issue should be to unravel the potential mechanical causes triggering recurrent focal ISR4. In this regard, intracoronary imaging remains the best strategy, although the previously discussed problems of catheter lengths must be considered. From the images provided, it appears clear that the stent was placed in the true anastomosis (i.e., crossing from the graft to the native vessel). In some patients “hinge” segments (active kinking points) may explain recurrent focal ISR. This scenario might indeed be a possibility according to the moving images provided. In extreme circumstances, this could generate a “stent fracture”4. Most investigators would select a drug-eluting stent (DES) rather than a drug-eluting balloon (DEB), should a stent fracture be identified. The same applies in cases with a focal pattern of “edge” ISR, although, again, the images suggest a focal ISR within the stent body. Incidentally, DES provide excellent results in mammary conduits5. Finally, in patients with resistant localised stent underexpansion, ultra-high-pressure non-compliant balloons should be used4. Optical coherence tomography has much higher resolution than intravascular ultrasound but this technique may be hampered if the bends of this winding conduit prevent adequate distal contrast flushing. As an alternative to intracoronary imaging, modern fluoroscopic stent enhancement techniques may also disclose stent-related mechanical problems.

Finally, once underlying mechanical problems have been ruled out or tackled, what would be the intervention of choice for this patient? In patients with BMS-ISR and DES-ISR current guidelines suggest the use of DES or DEB (recommendation/evidence: I/A)3. A DEB would be very attractive in this patient with permanent atrial fibrillation requiring chronic anticoagulation. However, ensuring maintenance of the best possible late angiographic result would also be of paramount importance in this particular case. In this regard, the RIBS IV trial (in patients with DES-ISR)6 and the RIBS V trial (in patients with BMS-ISR)7 demonstrated the long-term angiographic superiority of everolimus DES over DEB. Accordingly, in this challenging setting, the powerful antiproliferative properties of novel-generation DES will probably swing the pendulum in this direction.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

How did I treat?

ACTUAL TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE CASE

“Grandmother, mother and child”

The following treatment options were considered to treat the DES-ISR: simple balloon angioplasty, drug-eluting balloon angioplasty, drug-eluting stent implantation, CTO native vessel angioplasty or repeat CABG.

After discarding a fourth CABG and a CTO native vessel attempt (due to a challenging lesion with a J-CTO score of 4 points and jailed by a previous stent) we chose PCI of the in-stent restenosis with a different DES (everolimus)8.

The treatment dilemmas at this point were the following:

1. Technical difficulty in gaining access to the lesion due to its length and tortuous approach.

2. Unavailability of appropriately sized (short) guide catheter to reach the lesion via the brachial approach.

3. Inadequate support with risk of balloon slippage during inflation.

With those problems in mind we designed a triaxial “grandmother, mother and child” system with the double objective of achieving a high support and an adequate length guide catheter system.

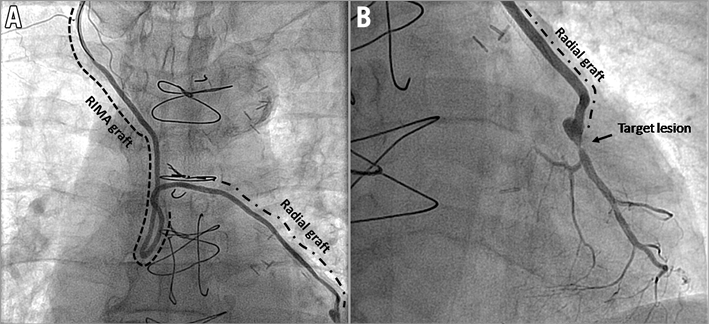

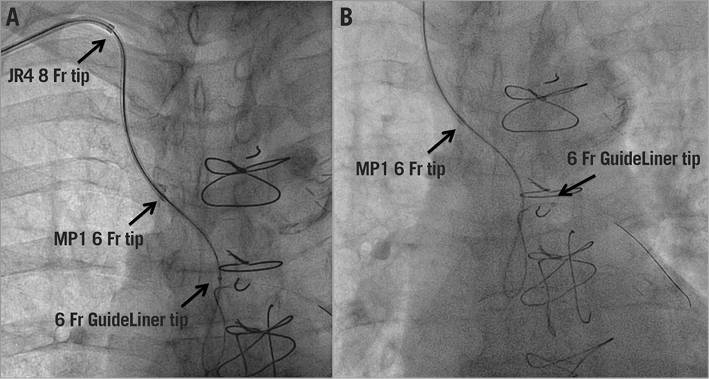

Design system (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Triaxial delivery system. Proximal portion (A), distal portion (B) and the whole assembled triaxial grandmother-mother-child system (C). A Judkins right 8 Fr guiding catheter (line) shortened and connected with a 7 Fr introducer (arrowheads), a Multipurpose 6 Fr guiding catheter (dashed line) shortened and connected with a 5 Fr introducer (arrowheads) and GuideLiner V3 catheter (dotted line).

Grandmother: an 8 Fr Judkins right guide catheter was shortened by around 40 centimetres and connected with a 5 centimetre segment of a 7 Fr introducer. The final catheter measured ~60 centimetres.

Mother: a 6 Fr Multipurpose (MP) guide catheter was shortened by around 20 centimetres and connected with a 5 Fr introducer. The final catheter measured ~80 centimetres.

Child: a 6 Fr GuideLiner inserted into the shortened MP.

Procedure

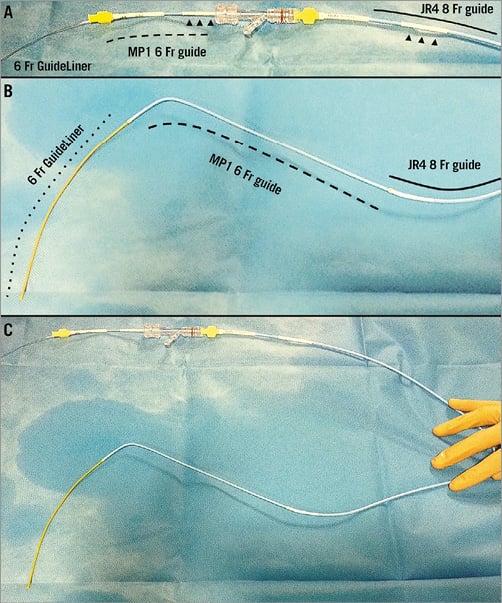

Initially, the RIMA was engaged with an internal mammary diagnostic catheter over the shortened 8 Fr guide and a 0.035” GLIDEWIRE® (Terumo Medical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was placed in the mid segment of the graft. Then, a diagnostic catheter was exchanged for a pre-assembled 6 Fr MP1 + 6 Fr GuideLiner V3 catheter (Vascular Solutions). This mother and child system was then advanced, the 6 Fr MP guide catheter was placed in the mid segment of the RIMA (Moving image 3), and the GuideLiner was advanced to the second bend of the graft (after the anastomosis RIMA-radial artery) (Figure 4, Moving image 4).

Figure 4. Fluoroscopic images of the system advancing into the graft (A) and the final position of the system (B).

The lesion was crossed with a SION guidewire (ASAHI Intecc, Aichi, Japan) and predilated with 1.5×10 mm Sprinter® Legend (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and 2.5×12 mm Emerge™ (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) balloons. A 2.5×12 mm SYNERGY™ DES (Boston Scientific) was advanced but could not cross the final bend in the graft anastomosis to marginal branch (Moving image 5). Finally, using a HIGH-TORQUE BALANCE HEAVYWEIGHT (BHW) guidewire (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as a buddy wire (Moving image 6), the stent was successfully implanted (Moving image 7) with a good angiographic result (Figure 5, Moving image 8). Although the whole system was partially occluding the flow, having the system pre-assembled allowed a fast PCI procedure with only mild chest discomfort during the procedure. Small injections of 2-3 ml of contrast were enough to guide the PCI with a final volume of 86 ml. There were no post-procedural complications. The patient remained free from angina and was discharged 48 hours post intervention. At two-month follow-up the patient was in NYHA functional Class II without angina.

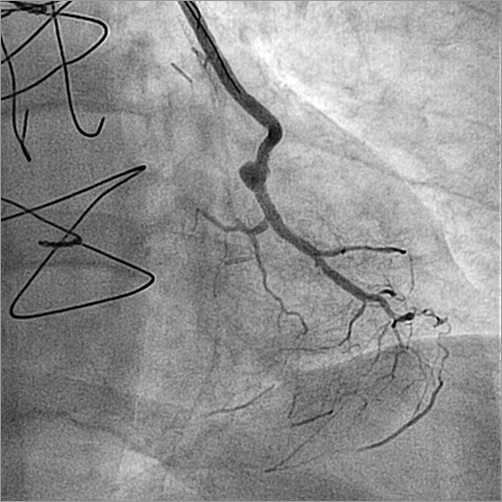

Figure 5. Final successful result after PCI.

Discussion

There are several discussion points including access site, selection of guide catheter with a long and safe extension and good support, and the type of device to implant in DES-ISR. We chose the brachial artery puncture site to shorten the distance to the vessel ostium, because in the first attempt the balloon did not reach the stenosis via the femoral route. The most important challenge was to create a long system which allowed us to advance with assurance (safety) throughout the graft and provide a high level of support to reach the stenosis. With this purpose, and based on the triaxial system often used in neuroradiology interventions9, we created the above-mentioned system with a “grandmother, mother and child”. Although a DEB could have been a good option in order to avoid a new stent layer, with similar results in short-term clinical outcomes and target lesion revascularisation compared to DES10, finally we preferred a DES implantation because the last attempt at angioplasty (June 2015) with a DEB (SeQuent® Please balloon; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) did not cross the stenosis. Moreover, recent studies have shown superior long-term clinical and angiographic results with EES compared with DEB in patients with DES-ISR2,6.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

Moving image 1. RIMA-radial graft with DES-ISR at the radial-OM anastomosis.

Moving image 2. Radial-OM anastomosis with DES-ISR.

Moving image 3. Advancing the mother and child system.

Moving image 4. Final position of the mother and child system.

Moving image 5. Attempt to advance stent into the DES-ISR site.

Moving image 6. Stent advanced into DES-ISR with buddy wire.

Moving image 7. Stent successfully implanted in the DES-ISR site.

Moving image 8. Final successful result after PCI.