Myocardial revascularisation procedures are among the most common invasive procedures performed1,2. The procedures, the clinical scenarios and the patients, for whom these procedures are carried out, are quite diverse. An expert panel of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) has written an expert consensus document reviewing the options when patients with myocardial revascularisation “fail”3.

The paper consists of different scenarios for revascularisation failure. The suggestions for the management of these distinct groups of patients are then described. The document is of excellent quality, and the clinical scenario approach makes it useful to clinicians. While treatment options exist for revascularisation “failure”, these frequently involve more complex intervention, with often modest long-term results. Thus, while a sound approach to revascularisation is highly desirable, it behoves us to recall the counsel of Benjamin Franklin, who stated that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”.

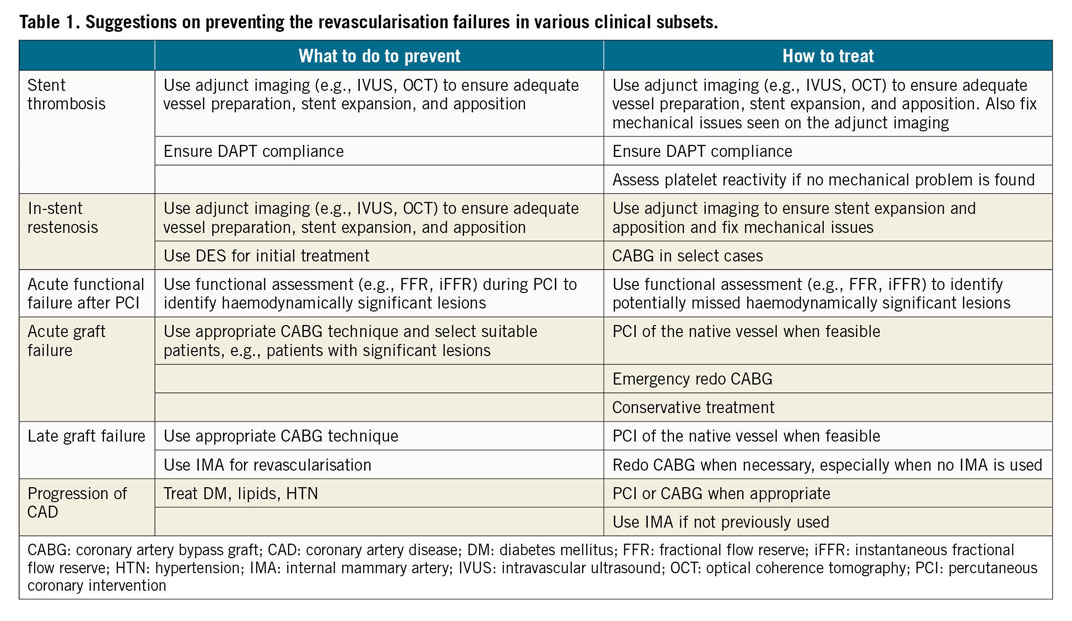

Importantly, as noted in the document, the majority of stent “failures”, particularly in the era of newer-generation drug-eluting stents, including both stent restenosis and thrombosis, are believed to be due to issues regarding the initial stent deployment. These factors include inadequate lesion preparation (particularly in cases of heavily calcified lesions), stent underexpansion, and stent malposition. Utilisation of intravascular coronary imaging (e.g., intravascular ultrasound [IVUS], optical coherence tomography [OCT]) has long been proposed to ameliorate unappreciated underdilation, although randomised study data supporting such routine use are sparse.

As with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), surgical graft failure within the first month is related mostly to graft spasm or suboptimal surgical technique4. Acute arterial graft failure may be related to technical issues regarding anastomosis of the internal mammary artery (IMA) to the coronary artery and is associated with a markedly higher rate of the composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), or repeat revascularisation5. The predictors of IMA failure include less severe left anterior descending artery (LAD) stenosis and additional grafting of the diagonal artery5.

In some cases, despite angiographically adequate revascularisation, patients experience little or no symptomatic improvement. As stated in the expert consensus document3, this may be the result of no functional assessment (e.g., fractional flow reserve [FFR], nuclear stress test) of the coronary anatomy before intervention. Without this, there may be either revascularisation of a non-haemodynamically significant lesion that is not the cause of the chest pain, or failure to appreciate the functional significance of other (perhaps “intermediate”) lesions subtending other coronary territories. Such cases of revascularisation “failure” (i.e., failure to relieve angina) could be prevented by prior functional assessment of such lesions, as is generally recommended (at least for stable chest pain) in both European and American guidelines6. Table 1 summarises the suggested methods used to prevent repeat revascularisation.

Many cases of what is ultimately labelled as myocardial revascularisation failure are related less to the treated lesion or lesions, and more to unabated progression of atherosclerosis, both in the target vessel and throughout the coronary tree. Neither a stent nor a vein graft alone is a substitute for aggressive secondary preventive measures, including smoking cessation, aggressive cholesterol treatment, and blood pressure lowering.

The expert consensus document on myocardial revascularisation failure3 is a welcome addition to the literature on the management of patients with coronary artery disease. We must, however, also remember that factors such as appropriate haemodynamic assessment of lesion significance, optimum lesion preparation and stent deployment in the case of PCI, surgical techniques and utilisation of arterial conduits, compliance with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), and aggressive secondary prevention measures can all decrease the incidence of myocardial revascularisation failure. In short, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.