The 2018 Guidelines on myocardial revascularisation1 represent the third iteration of a series of practice guidelines2,3 that are prepared jointly by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), with a special contribution from the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). The respective task forces, guideline committees and reviewers are empowered to craft a patient-centric and practical set of recommendations that integrate the ever increasing body of evidence in the field, technical advances and feasibility, procedure-related risks and long-term outcomes. Informed by the enlightened advice of their caring team, patients can then make contextualised decisions about their treatment choices and the combination of medical management and revascularisation approaches that works best for them.

The first Guidelines in 2010 set the stage and launched a new era of formal and irreversible collaboration between (interventional) cardiologists and surgeons which is exercised each week during local Heart Team conferences2,4.

The 2014 Guidelines3 have contributed to a better understanding of the growing prognostic impact of revascularisation procedures, beyond symptomatic relief, through iterative improvements in devices and procedures, highlighting the effective synergy between drugs and devices, as demonstrated in a companion network meta-analysis by Windecker et al5. This pivotal study initiated by the Guideline Task Force showed how technological advances from balloon angioplasty to stented percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents (DES) have a life-saving impact, modulated by the severity of the underlying disease. Myocardial revascularisation by coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or PCI of more extensive ischaemic disease resulted in greater prognostic benefit5.

The 2018 Guidelines1 have been equally impactful, revisiting the relative effect on mortality of contemporary CABG versus PCI from the results of a pooled analysis of individual patient data by Head et al6 and another companion, explanatory manuscript by Windecker et al7.

Four essential key messages of the 2018 Guidelines on myocardial revascularisation1 are summarised below.

Revascularisation ought to be complete

The decrease of residual stress-induced ischaemia to less than 5% after revascularisation reduced the risk of death and myocardial infarction (MI) in the COURAGE trial8. Complete revascularisation by anatomy is defined as the revascularisation of all epicardial vessels with a diameter of more than 1.5 mm and a luminal reduction of more than 50% diameter stenosis in at least one angiographic view. A meta-analysis of 89,883 patients enrolled in randomised clinical trials and observational studies using the same anatomical definition found a lower long-term mortality (relative risk [RR] 0.71), reduced rates of MI (RR 0.78) and repeat myocardial revascularisation (RR 0.74) by complete versus incomplete revascularisation9. The prognosic benefit was independent from the type of revascularisation. A post hoc analysis of the SYNTAX trial confirmed inferior long-term outcome after incomplete revascularisation, independently from the mode of revascularisation10. After PCI, a residual SYNTAX score of >8 was associated with significant increases in the five-year risk of death and of the composite of death, MI, and stroke, and any residual SYNTAX score >0 was associated with an increased risk of repeat intervention11.

Targets for revascularisation by PCI are best identified by combined anatomical and functional guidance

Functionally complete revascularisation is obtained when all lesions causing ischaemia are treated. With PCI, the FAME family of trials has demonstrated that fractional flow reserve (FFR) guidance decreases medium-term major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) versus angiographic guidance12.

The role of FFR guidance for bypass surgery is still a matter of debate. The recently reported FFR versus Angiography Randomization for Graft Optimization (FARGO) trial found that FFR-guided CABG had similar graft failure rates and clinical outcomes to angiography-guided CABG13. The FARGO trial does not provide definitive conclusions due to the limited power of the study (enrolment stopped prematurely at 58% of the planned target, low angiographic follow-up at 74% of enrolled patients) and does not apply to “state-of-the-art” arterial surgery (vein grafts, less sensitive to competitive flow, were used in 67% of cases). Not available to the 2018 task force, the prospective double-blind IMPAG trial14 showed a significant association (p<0.001) between preoperative FFR values and function of arterial anastomoses at six months. A preoperative FFR value of ≤0.78, indicative of a functionally obstructive stenosis, was associated with a low anastomotic occlusion rate of 3%.

Optimal CABG and PCI procedural techniques should be implemented

Complete revascularisation is recommended during surgical revascularisation (class I level B) with minimal aortic manipulation especially in the presence of aortic calcification (class I level B). Imaging of the aorta with computed tomography prior to surgery or epi-aortic ultrasound should be considered to identify atheromatous plaques and select the optimal surgical strategy (class IIa level C). Intraoperative graft flow measurements should be considered in order to assess the graft patency (class IIa level B). CABG should always use the left internal mammary artery (IMA) to the left anterior descending coronary artery (class I level B). The use of additional arterial graft(s) is highly recommended. The radial artery is superior to saphenous vein grafting in high-grade coronary artery stenosis (class I level B). Bilateral IMA should be considered in a patient with a low risk of sternal wound infection (class IIa level B). For harvesting of the IMA, skeletonisation is recommended in order to decrease the risk of sternal wound infection (class I level B). Endoscopic harvesting of venous conduits, in experienced hands, should be considered in order to reduce the incidence of wound complications (class IIa level A). With the open technique, “no touch” vein harvesting should also be considered (class IIa level B). These are some of the key elements of “best practice CABG”.

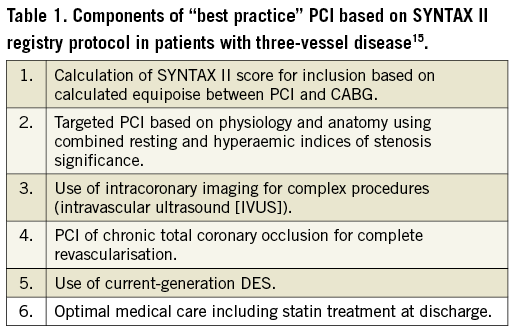

As to PCI, the components of “best practice” (Table 1) have been identified and have been shown to provide superior results at two years (13.2% MACCE) in the SYNTAX II registry15. Contemporary “best practice” PCI was non-inferior to CABG results: 13.2% vs. 15.1% MACCE at two years, when compared to matched historical CABG subgroups from the SYNTAX I randomised trial (p=0.42). Contemporary “best practice” PCI was superior to “historical” PCI results: 13.2% vs. 21.9% MACCE at two years, when compared to matched PCI subgroups from SYNTAX I (p=0.001). Although exploratory, these analyses do capture the latest progress in PCI results and should encourage operator teams to implement the components of “best practice” PCI through standardised procedural technique and clinical care.

Intervention decisional tree for patients with chronic coronary syndromes

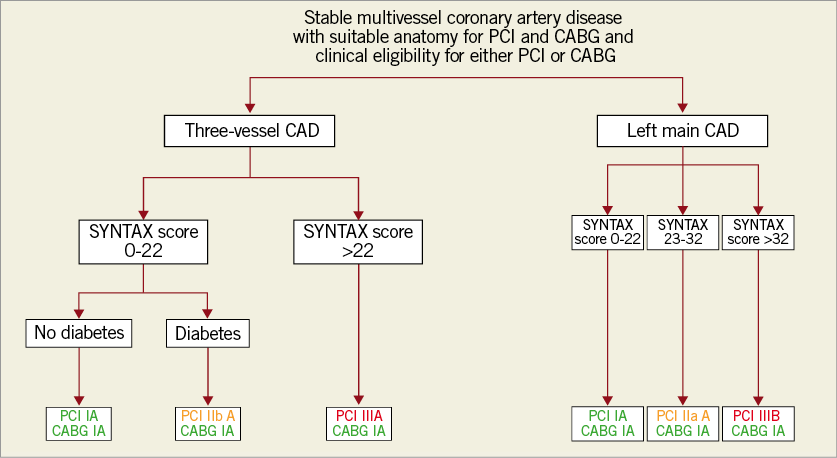

Based on a pooled analysis of data from 11,500 individual patients6, the evidence level for PCI has been increased to level A for multivessel and left main (LM) disease in several subgroups. CABG portends a significant survival benefit at a mean follow-up of 3.8 years, with a linear increase in the mortality hazard ratio with increasing anatomic SYNTAX score tercile. For LM stenting, the risk of mortality was not significantly different at a mean follow-up of 3.4 years. In patients with LM disease and a low SYNTAX score (0-22), MACE outcomes are similar for PCI and CABG, resulting in a class I A recommendation for both approaches. As to LM patients with a high SYNTAX score, the numbers are smaller, such that risk estimates and confidence intervals are imprecise, but suggestive of a trend towards better survival with CABG. For PCI in LM with intermediate anatomical complexity, the 2014 class IIa recommendation was maintained; a class III B was maintained for PCI in patients with a high SYNTAX score (>32). In patients with diabetes and triple-vessel disease, the recommendation for PCI is IIb A for scores 0-22 and remains III A for scores above 22. A simplified decision tree is shown in Figure 1, to be enriched with all other clinical and relevant variables for discussion by the Heart Team.

Figure 1. Algorithm to guide the choice of revascularisation procedure across major categories in patients with multivessel or left main coronary artery disease. Class recommendations correspond to the 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Windecker et al, reproduced with permission from the European Heart Journal7. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Following their August 2018 release at the ESC Congress in Munich, the Guidelines on myocardial revascularisation belong again to the group of five most cited and five most read manuscripts published in the European Heart Journal. Since then, a number of new trials have been published, as reviewed in the article that summarises “The year in cardiology 2018: coronary interventions”16. Considered together, these two essential manuscripts provide an up-to-date and robust basis for proper clinical decision making in the adequately informed, individual patient, until … experts from both ESC and EACTS again revisit the matter and come up with the 2022 issue of their joint revascularisation Olympics.

Conflict of interest statement

W. Wijns reports research grants from Terumo, Abbott Vascular and Biotronik to his previous institution (CV Research Center Aalst, Belgium); speaker fees from Biotronik; Steering Committee member and co-PI of trials supported by MiCell, Terumo, and MicroPort; Medical Advisor of Rede Optimus Research and co-founder of Argonauts Partners, an innovation facilitator. D. Glineur has no conflicts of interest to declare.