Abstract

Aims: Long-term health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in the elderly after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is unknown. We 1) compared HRQOL of elderly (≥70 years) with younger patients (<70 years) at 6, 12, 36 months post-PCI, and 2) examined whether predictors of impaired HRQOL 36 months post-PCI differed between older and younger patients.

Methods and results: A prospective cohort of 651 PCI patients (26.3% ≥70 years) completed the SF-36 at 6, 12 and 36 months post-PCI. Older patients experienced a poorer physical HRQOL at all time points and worse mental HRQOL with respect to vitality and role emotional functioning (all p-values<0.05). By 36 months, the HRQOL for the older patients worsened in five of the eight subdomains (all p-values<0.05). Younger patients did not experience enduring changes in HRQOL, with the exception of role physical functioning. Predictors of impaired HRQOL were generally different for the elderly (diabetes, previous PCI) compared to younger cohorts (smoking, previous bypass surgery, ACE inhibitors), although poor six-month HRQOL, anxiety and depression were common predictors for both groups.

Conclusions: Elderly PCI patients experience a deteriorating and poorer HRQOL than younger patients across three years. Contrary to younger patients, three-year HRQOL of elderly patients is irrespective of adverse events during outcomes.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a condition that manifests itself predominantly with older age. With greying populations worldwide, the number of elderly patients with CAD is increasing. However, most clinical trials exclude older individuals1-3. In the past, more than 50% of the CAD trials did not enrol any patients over the age of 752.

For this reason, little is known about the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in the elderly after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The few studies that have investigated HRQOL as a function of age have either not examined PCI in particular, or been limited by a relatively brief follow-up period4-10 or small sample size11,12. The results of these studies are also largely inconsistent, with some studies showing positive effects4,9, negative effects6,7,12 or even no effect8,11 of increasing age on physical HRQOL. Similarly, the association between mental HRQOL and age remains inconclusive.

As PCI is increasingly being performed in older patients, information on the long-term HRQOL after PCI in such older patients is clearly needed. Only with such information can older patients be counselled effectively following a PCI. The objectives of this study were, therefore, twofold: 1) to compare the HRQOL of elderly PCI patients (≥70 years of age) with that of younger patients (<70 years) at 6, 12, and 36 months post-procedure, and 2) to see if predictors of impaired HRQOL at 36 months post-PCI differed for older versus younger patients.

Materials and methods

PATIENTS

Between October 16, 2001, and October 15, 2002, 875 consecutive PCI patients were recruited into the psychological substudy of the RESEARCH registry13. Details and results of the study have been published elsewhere14. In brief, the aim of this single-centre study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) compared with bare metal stents. All consecutive procedures were included and no specific clinical or anatomical exclusion criteria were applied, so that patients represent those seen in clinical practice.

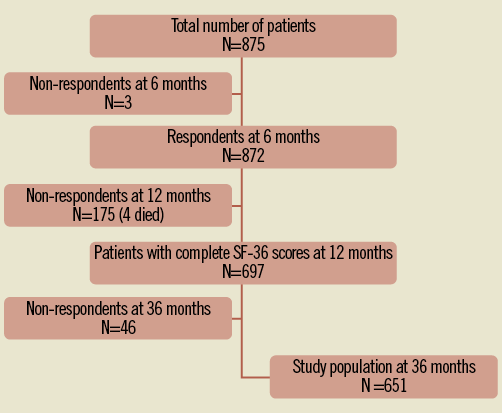

For the present study, 6, 12 and 36-month self-report questionnaires were sent by post to all surviving patients. A six-month assessment was chosen as a baseline to ensure that patients were in stable medical condition. A similar approach has been applied in other studies on PCI patients15. A reminder was sent to those who had not responded to the initial questionnaire. Only patients (N=651) who completed the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaires at all time points (i.e., 6, 12, and 36 months post-procedure) were eligible for inclusion in the current study (Figure 1). The overall response rate was 71%. Compared to non-responders, responders were more likely to use aspirin (96.6% vs. 93.3%; p=0.03) and less likely to have hypertension (30.1% vs. 37.5%; p=0.04) and diabetes (12.9% vs. 21.0%; p=0.003), anxiety and/or depression (32.4% vs. 51.3%; p<0.01). No other significant differences were found between responders and non-responders in terms of baseline characteristics.

Figure 1. Flowchart of attrition in the patient cohort.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected one month after PCI. Socio-demographic characteristics included age and sex. Clinical variables (i.e., risk factors, cardiac history and medication) were collected prospectively. Hypercholesterolaemia was defined as total cholesterol levels ≥240 mg/dL or statin use. Patients were regarded as having hypertension and diabetes if they were treated for the conditions. Renal impairment was indicated by creatinine clearance <60 mL/min.

HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE ASSESSMENT

The primary outcome was patient HRQOL at three years after PCI, which was measured by the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey. The SF-36 assesses eight self-reported aspects of HRQOL, including physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional functioning, and mental health16. Scoring of the SF-36 for the original eight scales was based on the methods of Ware et al17. The scores for all SF-36 subdomains range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating better wellbeing. The SF-36 has adequate reliability, with a median Cronbach’s α of 0.8518.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Patients were divided into two age groups: those <70 years of age and those ≥70 years of age. For descriptive purposes, discrete variables were presented as frequencies and compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were reported as the mean±SD and compared using the Student’s t-test for independent samples.

Univariable analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was used to evaluate the impact of age on HRQOL across the three time periods (i.e., 6, 12 and 36 months), with age (<70 years vs. ≥70 years) being used as the between-subjects factor and time as the within-subjects factor. Additionally, a sub-analysis was conducted for the following age groups: <60 years, 60-70 years, 70-80 years, and ≥80 years, to understand better the impact of age on HRQOL. A Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons of changes in HRQOL between different follow-up periods. Cohen’s effect size index was used to assess the clinical relevance of age in relation to HRQOL at 6, 12 and 36 months19. An effect size of 0.20 is considered small, 0.50 medium and ≥0.80 large. To investigate the effect of adverse events during the outcomes (i.e., MI, repeated revascularisation) on HRQOL, additional sub-group ANOVA for repeated measures was performed.

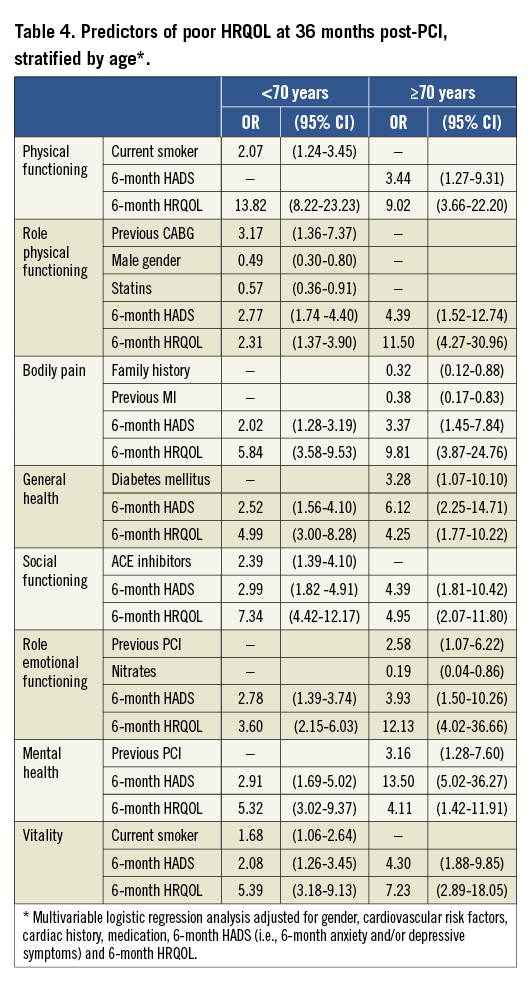

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent effect of dichotomous age on HRQOL, and to identify predictors of impaired HRQOL at three years in the elderly and younger cohorts separately. As advocated by others, we dichotomised the HRQOL domains to increase clinical interpretability20,21. The lowest tertile of the SF-36 scores was used to indicate poor HRQOL, with the other two tertiles representing good HRQOL. Since we were restricted by the total number of parameters in our multivariable model, the multivariate analyses were conducted in two steps. In the first step, all baseline characteristics were entered in the multiple logistic model and only those that were significant at p<0.05 were entered in the second step (i.e., gender, family history, current smoking, diabetes, previous MI, previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) or previous PCI and use of ACE inhibitors, nitrates and statins). Furthermore, all eight SF-36 subdomains were also adjusted for poor HRQOL at six months and six-month anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. Levels of anxiety and depression were assessed using the Dutch version of the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)22, where scores ranging from 0 to 7 indicated normal levels and scores ranging from 8 to 30 indicated anxiety and depression.

All statistical tests were two-tailed and a p-value of <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. For logistic regression analyses, odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The study protocol conforms to the ethical human research committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Every patient provided a written consent.

Results

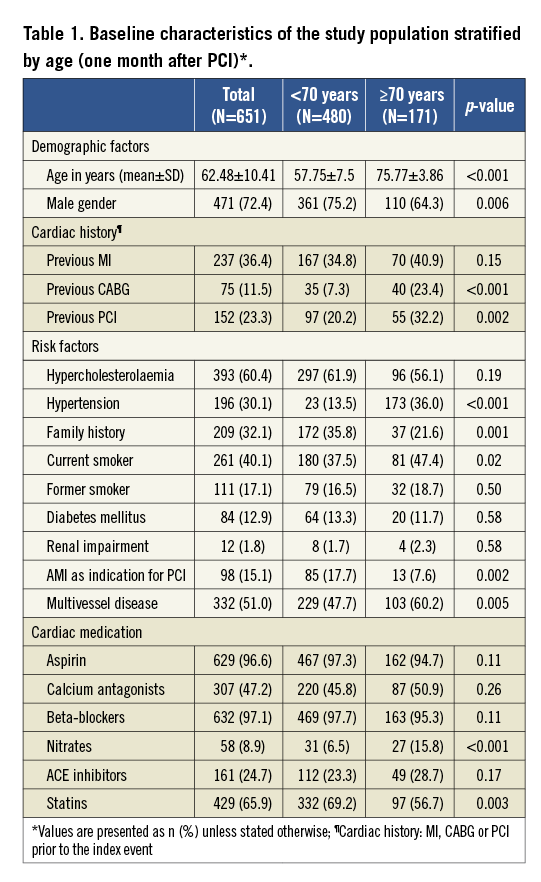

Of 651 patients enrolled in the study, 171 (26.3%) were ≥70 years old. Baseline characteristics of the study population at one month are presented stratified by age in Table 1. In general, older patients were more likely to be female, to smoke, to have hypertension, to suffer from multivessel disease, to have undergone a bypass surgery or PCI, and to use nitrates, as compared to younger patients. Older patients were less likely to have a family history of cardiac disease, to receive primary PCI, and to use statins. No other statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between the two groups.

HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE AT 6, 12, AND 36 MONTHS

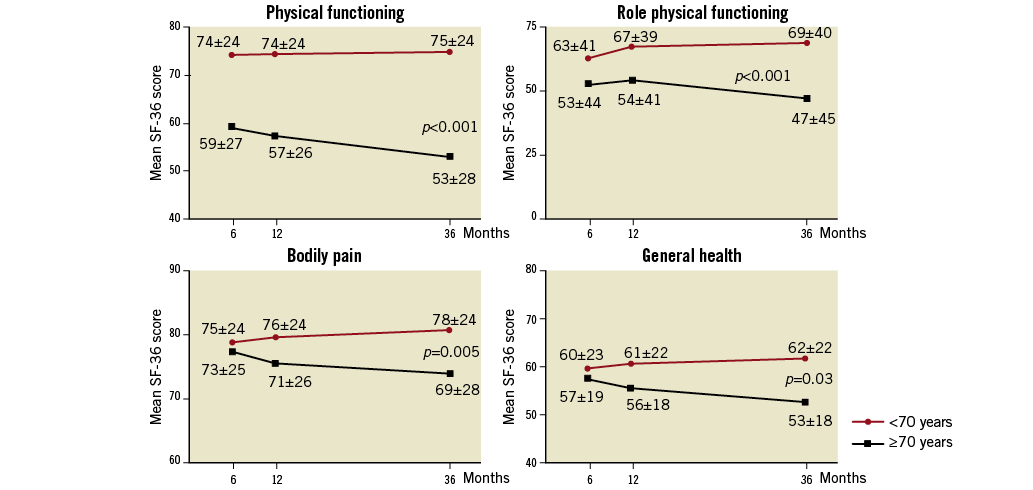

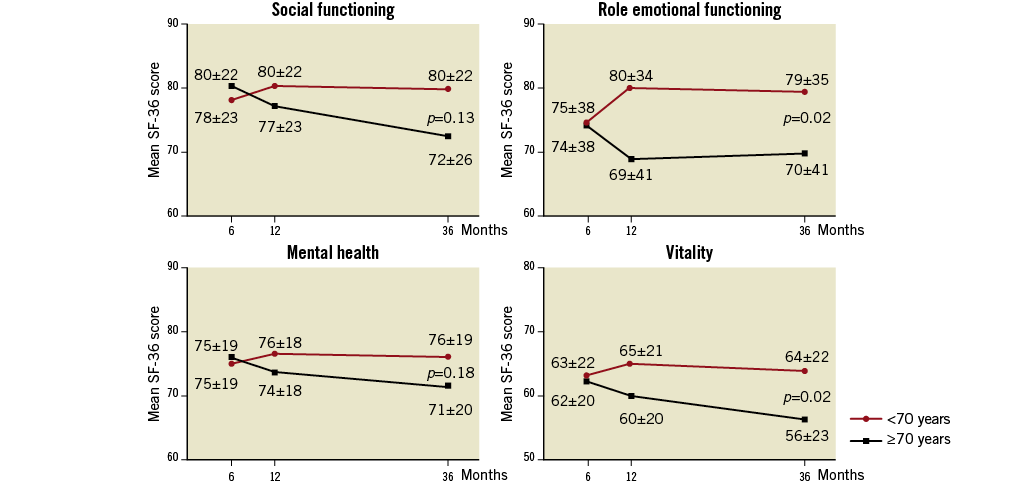

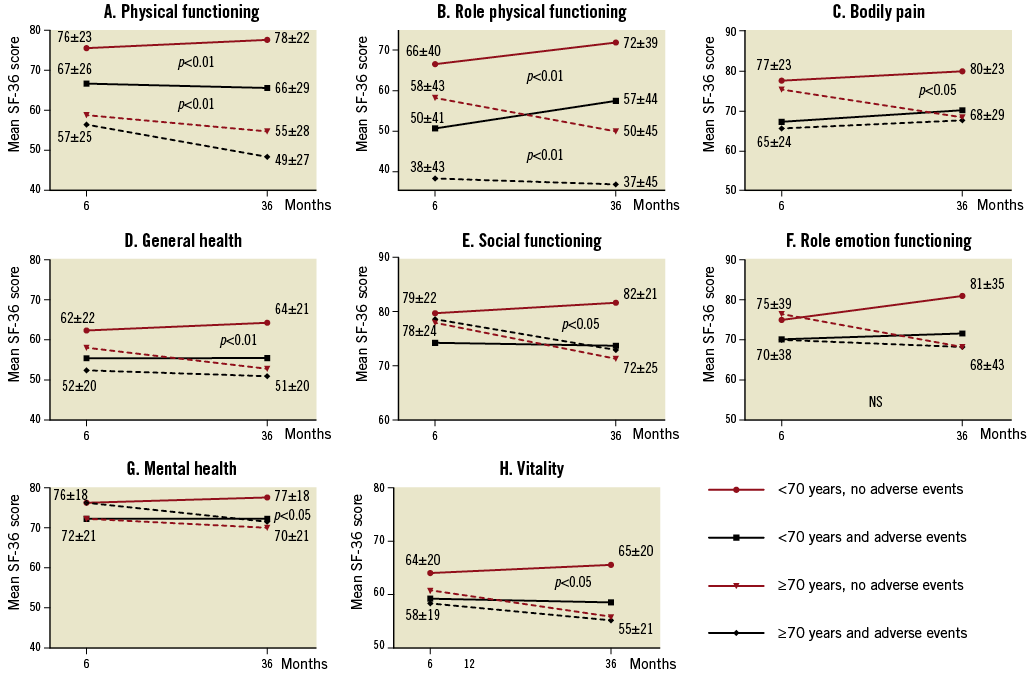

Unadjusted physical and mental HRQOL outcomes were compared between elderly (≥70 years) and non-elderly (<70 years) patients, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Based on mixed-design ANOVA, we found statistically significant between-group differences in all physical HRQOL domains (all p-values <0.05), with older patients experiencing poorer physical HRQOL at all time points (Figure 2). With regard to the four mental HRQOL domains (Figure 3), those ≥70 years of age again reported a worse HRQOL than those <70 years of age. However, the noted differences were significant only for vitality and role emotional functioning (all p-values<0.05).

Figure 2. Physical HRQOL domains (means and SDs) at 6, 12, and 36 months stratified by age. Univariable analysis of variance for repeated measures; a high score indicates better HRQOL, with a high score on bodily pain representing absence of pain. p-values for the between-group differences are listed.

Figure 3. Mental HRQOL domains (means and SDs) at 6, 12, and 36 months stratified by age. Univariable analysis of variance for repeated measures; a high score indicates better HRQOL. p-values for the between-group differences are listed.

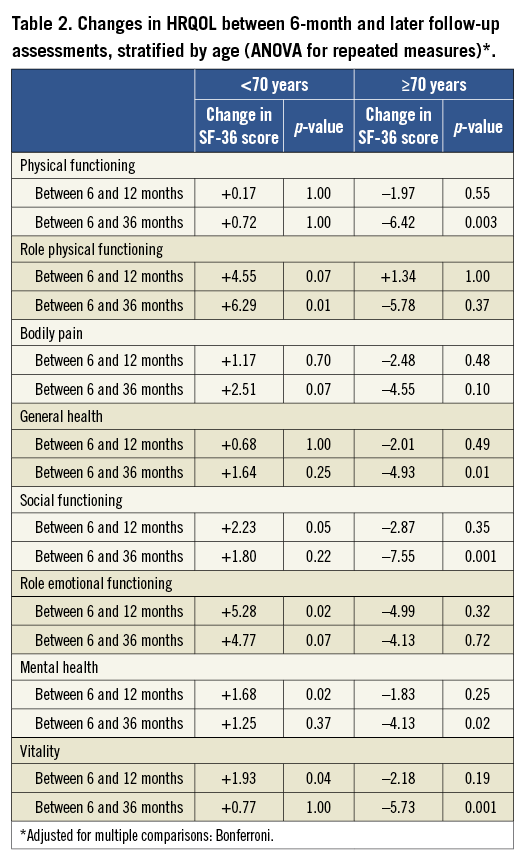

The effect of time was observed in most subdomains and was significant with regard to physical functioning, social functioning and vitality (p<0.05). In addition, the interaction effect for time by age was significant for all SF-36 subdomains, indicating that HRQOL scores changed over time and varied according to the age group. In all subdomains, the HRQOL of younger patients improved over time, whereas the HRQOL for the older patients worsened. Physical HRQOL of the younger patient group improved throughout the follow-up period (Table 2), but the increase was only significant for role physical functioning at 36 months (+6.29 points; p<0.05). Between six and 12 months, mental HRQOL scores of the younger cohort improved in all subdomains but this initial benefit disappeared by 36 months. By 12 months, both physical and mental HRQOL in the older cohort had worsened slightly. However, the decline in HRQOL was not significant. The downward trend continued over the follow-up period and, by 36 months, the decrease in SF-36 scores was observed in all domains and was significant for five domains: physical functioning (–6.42; p=0.003), general health (–4.93; p=0.01), social functioning (–7.55; p=0.01), mental health (–4.13; p=0.02) and vitality (–5.73; p=0.01). Taken together, the HRQOL of the older patients worsened by 36 months, whereas the younger patients did not experience enduring changes in HRQOL, except for improvement in role physical functioning.

To understand better the impact of age on HRQOL, an additional sub-group analysis was performed using four age cohorts: <60 years, 60-70 years, 70-80 years, and ≥80 years. Again, we found that older patients (70-80 years or ≥80 years) experienced poorer HRQOL than the younger PCI patients (<60 years or 60-70 years). These results corresponded with our analysis of two age cohorts (<70 years and ≥70 years) and no additional differences among the four age groups were found (data not shown).

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF THE INFLUENCE

OF AGE ON HRQOL AT 6, 12, AND 36 MONTHS

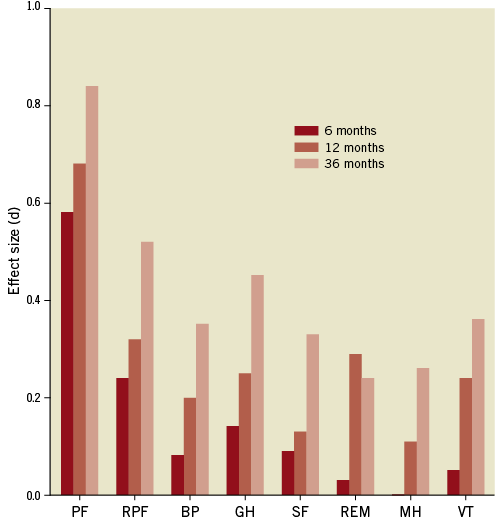

In order to examine the magnitude of the influence of age on HRQOL, Cohen’s effect size index (d) was calculated for all eight SF-36 subdomains, as presented in Figure 4. At baseline, the effect sizes for all but one category were small to negligible. Only in case of physical functioning was Cohen’s effect size moderate. However, at 12 and 36-month follow-up, the effect sizes were larger, indicating that differences in HRQOL between the two age cohorts increased over time.

Figure 4. Clinical relevance of the influence of age on HRQOL at 6, 12, and 36 months, as denoted by Cohen’s effect size (d). Cohen’s d: 0.2: small; 0.5: medium; 0.8: large. BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; MH: mental health; PF: physical functioning; REM: role emotional functioning; RPF: role physical functioning; SF: social functioning; VT: vitality

EFFECT OF ADVERSE EVENTS DURING THE OUTCOMES

ON HRQOL AT 36 MONTHS

As expected, younger patients without adverse events during the follow-up experienced the best HRQOL at three years (Figure 5). They scored significantly higher than any other studied cohort in seven out of eight SF-36 subdomains (p<0.05). However, younger patients with adverse events reported as poorly as all the older patients in six subdomains. Only in case of physical functioning and role physical functioning did younger patients with adverse events show a better 36-month HRQOL than the elderly.

Figure 5. HRQOL stratified by age and adverse events at 6 and 36 months.

In general, older patients scored poorly at 36 months, irrespective of adverse events during the outcomes.

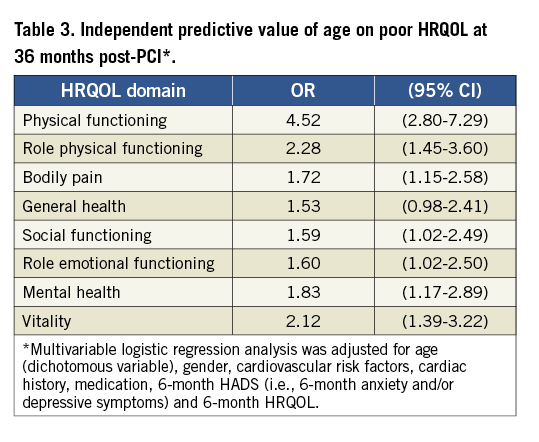

PREDICTORS OF HRQOL AT 36 MONTHS

In order to assess the independent effect of age on poor HRQOL at 36 months, multivariable logistic analysis was performed. As presented in Table 3, older age (≥70 years) was a significant predictor of impaired HRQOL in seven of the eight subdomains. It was a strong predictor especially for physical functioning (OR 4.52), role physical functioning (OR 2.28) and vitality (OR 2.12). As shown in Table 4, the predominant predictors of impaired HRQOL in the older cohort were diabetes, previous PCI, presence of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms at six months and poor HRQOL at six months. Independent predictors of better HRQOL in older patients included family history, use of nitrates and prior MI. In the younger cohort, smoking, history of bypass surgery, use of ACE inhibitors, presence of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms at six months and poor HRQOL scores at six months were significantly associated with impaired HRQOL at three years. Better HRQOL at three years was related to male gender and statins.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that, in contrast to younger patients, the HRQOL of patients ≥70 years of age worsened in all subdomains of the SF-36, whereas the HRQOL of younger patients remained stable or even improved by 36 months. Consequently, the differences between the groups increased during the three-year follow-up period, becoming clinically relevant for physical functioning, role physical functioning and general health, as indicated by Cohen’s effect size index. The three-year HRQOL of younger patients was negatively affected by adverse events during the outcomes. However, the three-year HRQOL of older patients did not significantly differ among the elderly, regardless of adverse events. Older patients, even without adverse events, performed as poorly as the young ones with events. Predictors of both impaired and improved HRQOL at 36 months were different for the elderly and the younger patients. The only common predictors in both groups were six-month anxiety and/or depressive symptoms and six-month HRQOL.

With regard to age-dependent HRQOL in cardiac patients, different results have been presented in the literature. Our findings that elderly patients experience worse physical HRQOL than younger patients were also found in previous studies in patients after AMI6, patients with CAD12 and after PCI7. However, poorer mental HRQOL among older PCI patients has not previously been reported. Several studies have reported results opposite to ours, finding that older age is a predictor of better rather than worse HRQOL4,8,10-12. This difference might be explained by a shorter follow-up period in these studies. An alternative explanation could be the use of the Physical (PCS) and Mental (MCS) Component Summary Scores instead of the eight individual subscales of the SF-36 in those studies23. Some authors have suggested that MCS and PCS inaccurately summarise subscale profiles24-27. For example, in a cross-sectional population study, using summary scores for comparison of an elderly with a younger cohort resulted in an incorrect estimation of mental health24. Even though the older group scored worse on all eight subdomains than the younger group, their MCS score turned out to be significantly better. Thus, we and others believe that the summary scores need to be interpreted with caution as they can produce results that would not be expected from the underlying subscales26-28.

The existing literature describes different time changes in HRQOL after PCI. While some authors reported improvements in HRQOL over the course of follow-up5, others noted no enduring changes29. To our knowledge, our findings that changes in HRQOL after PCI are age-dependent and vary between the younger and older groups have not been reported before. Previously, only one study compared HRQOL following PCI in elderly and non-elderly patients5 but, contrary to our findings, they did not find any differences in the recovery rate between the age cohorts. We can only speculate about the reasons for these contradictory results. A possible explanation might again be the use of summary scores in the previous study as MCS/PCS might yield inconsistent results.

A likely reason for deterioration in HRQOL of the older cohort could be anxiety and/or depression. Both anxiety and depression have previously been associated with impaired HRQOL21,30. Also in our study, the presence of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms at six months post-PCI was a significant predictor of poor HRQOL at follow-up, both in younger and older patients. However, in older patients, anxiety disorders and depression are often concomitant with physical conditions and therefore misdiagnosed as a normal part of the aging process. They remain undetected and undertreated, even though they are quite common in the elderly31-33.

Our study has certain limitations. We had incomplete information on New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and we did not include it in our analysis, which might have influenced HRQOL in elderly patients34.

The strengths of our study include the large study sample, the long follow-up period of 36 months, and the multiple assessments of HRQOL. In addition, our study population consisted of “real world” PCI patients, i.e., patients with all their comorbidities and to whom no anatomical or clinical exclusion criteria were applied. Almost 70% of our patients would not normally have qualified for inclusion in clinical trials14, even though they reflected a true population seen in daily clinical practice. This approach has facilitated generalisability of our results, as advocated by others35.

Conclusions

In conclusion, elderly PCI patients reported deteriorating and poorer HRQOL than their younger counterparts over a period of three years. Contrary to younger patients, three-year HRQOL of elderly patients was irrespective of adverse events during the outcomes. These findings should be taken into account in post-revascularisation counselling and treatment. It is important to inform elderly patients about the likely course of the disease in order to avoid expectations that cannot be fulfilled. Furthermore, anticipating this trend towards diminished HRQOL, physicians, nurses and other healthcare givers could tailor a treatment that aligns with the long-term needs of the older PCI patients. Consequently, elderly PCI patients with anxiety and depression, diabetes and a history of prior percutaneous intervention should receive extra medical attention in order to prevent deterioration of HRQOL.

Funding

No extramural funding was used to support this work. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study; all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper, and its final contents.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.