Abstract

The current article summarises more than 12 years’ experience in the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the Małopolska region (southern part of Poland). Data on the development phase of the STEMI treatment network, as well as the current status of interventional treatment of acute coronary syndromes in that region of Poland are provided.

Abbreviations

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Development of the network

The Małopolska region is one of Poland’s 16 administrative provinces, with Krakow as the capital city. This region encompasses approximately 3.2 million inhabitants (0.75 million in Krakow city) in a partially mountainous region, especially to the south (the Tatra Mountains).

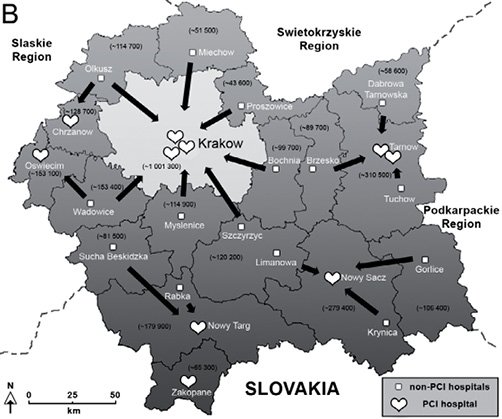

Until 1999, patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) were treated in the closest local hospital with either thrombolysis (hospitals without cathlab facility on site) or primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on a daily basis in the Institute of Cardiology in Krakow. In 1999, the Department of Interventional Cardiology of the Jagiellonian University Medical College in Krakow started a 24 hours/7 days PCI service for the population of the city of Krakow and surrounding areas for expected delays less than 90 minutes from the diagnosis of STEMI to PCI (Zone I; Figure 1A)1-3. Ambulance services and seven Krakow non-PCI hospitals were included in this network for the treatment of STEMI. Duty days were divided between the two cathlabs operating within the Department of Interventional Cardiology (one in the University Hospital and the other in the John Paul II Hospital).

From June 2001, in order to provide PCI as the optimal method of reperfusion therapy for all STEMI patients in the Małopolska region, a new programme for the treatment of STEMI was launched. Patients with STEMI presenting <12 hours after symptom onset were transferred directly for primary PCI if the expected transfer delay to PCI was less than 90 minutes (Zone I; Figure 1A) just as they used to be transferred from ambulances in Krakow and non-PCI hospitals1,2. However, for the remaining 22 remote non-PCI hospitals outside Krakow (up to 150 km) with expected transfer delays to PCI over 90 minutes (Zone II; Figure 1A) patients received a combination of reduced-dose fibrinolytic therapy (alteplase) and full dose of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (abciximab) plus unfractionated heparin before and during transfer. Patients were transferred to the Department of Interventional Cardiology in Krakow for immediate routine coronary angiography followed by PCI, if needed (facilitated PCI with reduced-dose fibrinolysis, pharmaco-invasive approach)1,2. Ambulance cars with doctors on board and experienced dedicated paramedic staff, as well as physicians at Emergency Rooms of non-PCI hospitals and cathlab staff were trained to reduce unnecessary delays in order to promote simple, routine procedure algorithms for patients with acute STEMI. The so-called Krakow Program for the Treatment of Myocardial Infarction was accepted and supported by local government and healthcare providers for that region. Reimbursement for study drugs (abciximab, alteplase) was made available. The programme continued from June 2001 to June 2003. Study design and results were published in the American Journal of Cardiology and in the International Journal of Cardiology. Our programme was the first large one reporting the safety and benefits of transportation with very long transfer delay (>90 minutes) for facilitated PCI with reduced-dose fibrinolysis in STEMI patients. In our patients, pharmacological treatment (combo therapy) was effective in overcoming the deleterious effects of long time-delay on outcome (with median over 150 minutes), with similar survival as compared to short-time transportation, despite a higher risk of severe bleeding complications during hospital stay (3.4% vs. 1.1% for facilitated and primary PCI, respectively, p<0.0001)1,2.

Figure 1. The map of the Malopolska region, Poland, showing the geographical distribution of primary PCI and non-primary PCI hospitals in 2001 (Figure 1A) and 2012 (Figure 1B). Figure 1A reproduced and modified with permission from Elsevier, originally published in International Journal of Cardiology 2010;139:218-27. White hearts: primary PCI centres; white squares: non-primary PCI hospitals; numbers in parentheses: approximate population of each administrative unit. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

From 2003 onwards the already well-performing STEMI network served as one of a few in Europe in the enrolment to the randomised CARESS-in-AMI study. Study drugs now included abciximab and reteplase for high-risk STEMI patients. The results of the CARESS-in-AMI study confirmed that in high-risk STEMI patients immediate transportation to a PCI centre after fibrinolysis is superficial to routine transfer only in patients with no signs of reperfusion4.

Years 2005-2011

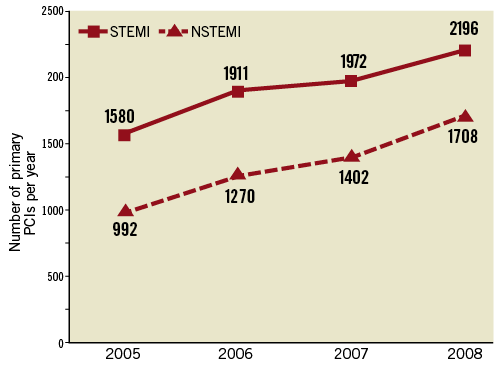

In 2005, two new PCI centres as local hub and spoke model (small network) in Tarnow and Nowy Sącz operating 24 hours/7 days were opened to provide a primary PCI service for a higher number of STEMI within the recommended time window from diagnosis to treatment (less than 90-120 minutes). The mechanical reperfusion rate (PCI) for STEMI patients presenting less than 12 hours from chest pain onset has risen from 12% in 2002 to 60% in 2006 in the entire Małopolska region2,3,5. However, in 2005 in the newly established networks in Tarnów and Nowy Sącz, these numbers were 78% and 88%, respectively, which puts it above the optimal European recommended level of reperfusion therapy for STEMI patients (as also recommended by the “Stent for Life” programme)3,5. It is also worth noting that the promotion of early reperfusion of STEMI by PCI in the region has led to an increase in the percutaneous treatment of NSTEMI patients, which is in line with current guidelines and the new universal definition of myocardial infarction (Figure 2). An additional centre in the mountainous southern part of the region was launched in 2007 in Nowy Targ. Then a primary PCI programme was started in Zakopane (2007), Oświęcim (2009), Chrzanów (2009), in an additional hospital in Tarnów (2010), and finally in one more centre in Kraków (2010) now covering almost 100% of the Małopolska region population with primary PCI services.

Figure 2. Number of primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in patients with ST-segment elevation (STEMI, solid line) and non-ST-segment elevation (NSTEMI, dotted line) myocardial infarction in the Malopolska region from 2005 to 2008. Data taken from the registry of PCI procedures of the Polish Society of Cardiology.

Acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel and unfractionated heparin were introduced as a standard therapy before transfer for primary PCI. However, PCI facilitation with abciximab for patients with estimated transfer delay of less than 90 minutes has been promoted in our STEMI network for some time6-9. A beneficial effect of such facilitation especially in early comers, high-risk STEMI patients (anterior wall myocardial infarction, diabetes, elderly) was observed in the EUROTRANSFER Registry (one-year mortality reduction after adjustment for covariates and propensity score in comparison to standard in-cathlab use of abciximab)6-10.

At the beginning of the year 2010 standardised protocols for transfer of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI were proposed by our team and accepted by the local government of the Małopolska region. Based on the new protocol, all STEMI patients are to be transferred by ambulance service directly to primary PCI centres bypassing emergency rooms of non-PCI community hospitals in order to decrease treatment delays. In the case of ambiguous diagnosis, the possibility of ECG teletransmission is available. NSTEMI patients are to be transferred to emergency rooms for initial assessment. The time window of 24 hours from symptoms onset to invasive diagnostics, especially in high-risk patients, was proposed. That protocol was finally published in the Kardiologia Polska (Polish Heart Journal) and accepted by the Polish Society of Cardiology as the standard of treatment for patients with acute myocardial infarction in Poland11.

Current status

As shown in Figure 1B, a primary PCI service is now available in the entire Małopolska region for the majority of the population (ten primary PCI centres operating 24 hours/7 days). Each centre now has its own network of co-operating non-PCI hospitals and ambulance services. Two PCI centres in the Institute of Cardiology in Krakow still serve as reference centres for the whole region in cases of complex PCI procedures, left main disease, advanced imaging techniques (IVUS, VH, OCT, cardiac MRI), as well as percutaneous aortic valve implantation. So even though the number of people at risk of STEMI for the Krakow city network is smaller, the number of procedures and their complexity are still high. Thrombolysis is scarcely used, mainly in bailout situations when a primary PCI service is for technical reasons unavailable, but only in early presenters up to two hours from chest pain onset, as recommended by the guidelines. In other cases patients can be transferred to the nearest available primary PCI centre with an acceptable delay.

In the case of ambiguous diagnosis, the possibility of ECG teletransmission was available in some local networks, but currently a systematic ECG teletransmission programme is being developed. A centre of coordination for acute myocardial infarction treatment in the whole Malopolska region was proposed as a joint initiative of local government, regional emergency medical services and the Institute of Cardiology of the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. The centre will be based on: 1) optimisation of transportation time, by selection of the nearest cathlab with the shortest transfer delay (based on GPS system); 2) ECG teletransmission which will facilitate the initial diagnosis; 3) information on cathlab technical failures and current availability of coronary care unit beds which will be taken into consideration during cathlab selection. The coordination centre will bring about a shortening of first medical contact to balloon time.

According to the statement of the Polish Society of Cardiology led by Dariusz Dudek, a new model of modern P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel, ticagrelor) initiation in the cathlab for STEMI patients instead of clopidogrel use, the so-called Model B, was introduced in the Małopolska region12.

Currently in the Małopolska region we perform about 2,300 PCI in STEMI and about 2,500 PCI in NSTEMI patients per year (the number of STEMI per million inhabitants per year in our region is about 700-750). Our idea was that each centre has to perform at least 250 STEMI cases per year in order to maintain high quality and efficacy standards. This could be achieved if one creates a STEMI network that covers a minimum population of approximately 300,000 to 500,000 inhabitants. It is worth noting that the staff of the Institute of Cardiology in Krakow are also responsible for the maintenance and training in the peripheral PCI centres in the Małopolska region. In our opinion, this is crucial for the success and similar high-level performance of each network and PCI centre.

Quality control measures

Registries are valuable tools for the assessment of current epidemiology and treatment patterns on an unselected patient cohort. We believe they are crucial in order to maintain high quality and efficacy standards. From June 2001 to June 2003, a central database of all STEMI patients treated by PCI in the Małopolska region was run in the Department of Interventional Cardiology in Krakow1,2. Simultaneously, a constant registry of all acute coronary syndrome patients treated in non-PCI hospitals in the Małopolska region was undertaken. Initially a paper registry, in 2005 it turned into a short-period reporting web-based registry. From 2002 to 2006, we gathered data for almost 4,000 patients in our region for a population of 3.2 million people2,3,5. Currently, we are responsible for two on-going registries: one is a constant registry of all PCI procedures of the Polish Society of Cardiology, while the other is our own internal registry of all PCI procedures in patients with acute coronary syndrome admitted to our cathlab. They are both web-based and include important data concerning time delays. Monitoring of time delays really tells the truth about the efficacy of a STEMI network, so it is vital to implement such a measure in every cathlab responsible for STEMI treatment3.

Our scientific activities are summarised twice a year during international workshops organised by the Department of Interventional Cardiology of the Jagiellonian University in Krakow: the New Frontiers in Interventional Cardiology (NFIC) every December since 1999 and Peripheral Interventions in Krakow (PINC) every June since 2004. For more information visit websites: www.nfic.pl and www.pinc.pl.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.