Introduction

In general, guidelines reflect scientific evidence already acquired and follow, rather than anticipate, new developments in diagnostic and therapeutic practice. This applies to STEMI guidelines. Failure to apply the guidelines is rarely caused by the lack of knowledge of their content. Resistance is invariably due to scepticism as to the true advantage of the treatment proposed, financial concerns or organisational difficulties. In the last 10 years the guidelines surrounding STEMI treatment have evolved from a list of drugs able to respond to the various needs of STEMI patients (from pain relief to haemodynamic stabilisation and antithrombotic treatment) to an integrated strategy describing in detail the response to this primary cardiovascular emergency (from the first diagnosis and treatment in the ambulance to rehabilitation and secondary prevention). This article reports the key messages of the guidelines addressing STEMI treatment in the past 10 years and reviews how these messages have informed key changes in clinical practice.

Primary angioplasty is the preferred treatment if performed by an experienced team <90 minutes after first medical contact

The first ESC guidelines clearly indicating that primary angioplasty was the treatment of choice when timeously performed by an experienced team were published in 20031. Retrospectively, we might ask ourselves whether these guidelines were timely enough since the first two large randomised trials using streptokinase2 or rtPA3 were published 10 years before, followed by a compelling meta-analysis of more than 3,000 patients showing advantages in mortality4. We must remember that at the time there was still heated discussion on the value of third-generation fibrinolytics and questions resulting from poorly interpreted registry data. The 2003 guidelines should be considered highly innovative because they gave the strongest possible recommendation (Class I, Level of Evidence A) to a practice that many still felt to be inapplicable in most situations. Also, in countries with advanced health services, it is seen as a distraction or an excuse to delay or prevent the application of fibrinolysis, as well as the other treatment readily available everywhere within minutes of diagnosis. With minimal changes in subsequent updates this guideline has become the cornerstone of STEMI treatment (Figure 1). We must thank Professor van der Werf and his co-authors for having given official approval to a therapy still felt by many at the time to be experimental or not practically applicable. This guideline faced the dilemma of defining an acceptable time delay in order that PCI remained superior to fibrinolysis. The issue is complicated by the basic knowledge that a minimal delay in the first hours after symptom onset causes much greater damage than the same delay after six or nine hours. A wrong interpretation of some early PCI trials suggested similar mortality irrespective of the time delay after symptom onset when PCI was used, a very different outcome than after fibrinolytics which also become less effective on old thrombi. More recently this mistake has been corrected based on the evidence of a worsening outcome according to the time delay between symptoms onset and PCI, more evident in high-risk patients5. The 2008 guidelines have identified a cohort of patients with large anterior infarctions and low bleeding risks in which a lower threshold (no more than 90 min delay) should be used, while the general time delay has been prolonged to two hours including also the delay between first medical contact and the transport to the hospital door6. Despite its clear formulation, the application of primary angioplasty has been very slow, to the point that an Immediate Past President of the ESC, Jean Pierre Bassand, felt the need to create a task force for promoting its implementation. The results of the survey, conducted in 2005, observed a large gap between guideline recommendations and clinical practice, with none of the large European countries having greater than 50% application of primary angioplasty, a treatment that looked suitable for small well-organised countries such as Netherlands, Belgium, Czech Republic or Switzerland but impractical elsewhere7. This was the driving force behind the first Stent for Life Initiative, and a repeat survey led by Petr Widimsky in 2008 showed that Germany, Poland, Sweden, Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia and others had come on board and great progress had been made in France and Italy8. No data could be obtained on the quality of the PCI performed and, in particular, in respect of the 90 min door to balloon time suggested at the time. A large on-going survey has been repeated, coordinated by Dr Kristensen on behalf of the SFL group, and data are expected to be reported in Munich at the ESC Congress. What can we expect based on current knowledge? A major increase in penetration of primary angioplasty will emerge, probably showing the fastest pace of progress since the introduction of primary angioplasty. The biggest positive surprise is certainly the UK and, since this is specifically addressed in a subsequent article9, we will not express more than admiration for a stunning performance moving from <40% in 2006 to >90% PCI in 2011. The UK has a unified national health care system and decisions taken in Whitehall apply to the entire country, a situation very different from Italy or France where patchy application mirrors different regional directives. Hospitals in the UK respond to authorities with the power to decide which hospital should perform PCI and regulate patient transfer accordingly. The UK had already developed an excellent system to administer timely fibrinolysis based on dedicated nurses in A&E. The system has immediately worked equally well when these resources have been allocated upstream, in the ambulance, with the personnel performing and interpreting the ECG and informing the closest primary PCI centre of the arrival of a STEMI patient. Thirdly, as indicated by Ludman et al in a separate chapter of this supplement, auditing was fully implemented via the MINAP ACS and BCIS PCI databases, offering the advantage of constant monitoring of quality indicators such as time delays and outcomes such as mortality. This advantage is shared with Sweden and it is interesting to know that data from both countries indicate impressive mortality benefit after the implementation of the universal primary PCI programme, together with cost reduction mainly generated by shorter hospital stay and immediate patient triage. Equally impressive results have been achieved in most of the 13 countries participating in the SFL Initiative. It is obviously impossible to distinguish the natural process of diffusion of a new therapeutic treatment from the additional push the participation of SFL gave to the programme. In Italy and Spain wide regional differences remain, with large regions such as Lombardy in Italy and Catalonia in Spain close to universal application of primary angioplasty and others still far behind (Figure 2). A similar situation may be said to exist in France with the additional complication in interpreting figures indicating that pre-hospital thrombolysis is still occasionally applied within this country, where it is seen not as an alternative but as a preparation for angioplasty. Characteristics specific to France are the reluctance of the SAMU, the very efficient equipped ambulances with an anaesthetist on board, to play a passive role simply shipping the patient to the closest angioplasty centre where mechanical recanalisation is performed. The results of CAPTIM10, at odds with all the other thrombolysis vs. primary PCI randomised comparisons because they saw superiority of thrombolysis within two hours from symptoms onset, must be interpreted in the context of a very atypical 80% use of angioplasty in the hours after fibrinolysis. Unlike in ASSENT IV11 there were no signals of higher morbidity and mortality when PCI immediately followed the administration of lytics, possibly because of the timely use with fibrinolysis of dual antiplatelet treatment. Unlike almost all the other trials of facilitated PCI (FINESSE12, etc.) there was no excess of bleeding, possibly because of the frequent adoption of a radial approach. However, the real surprise comes from the other countries participating in the SFL programme, starting from a very low penetration and expected to be limited by an insufficient number of 24/7 primary PCI centres and equipped mobile units for pre-hospital diagnosis. Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey have made impressive steps forward thanks to the ability of their countries’ champions to make primary angioplasty an absolute priority in receiving ample resources to meet their goals.

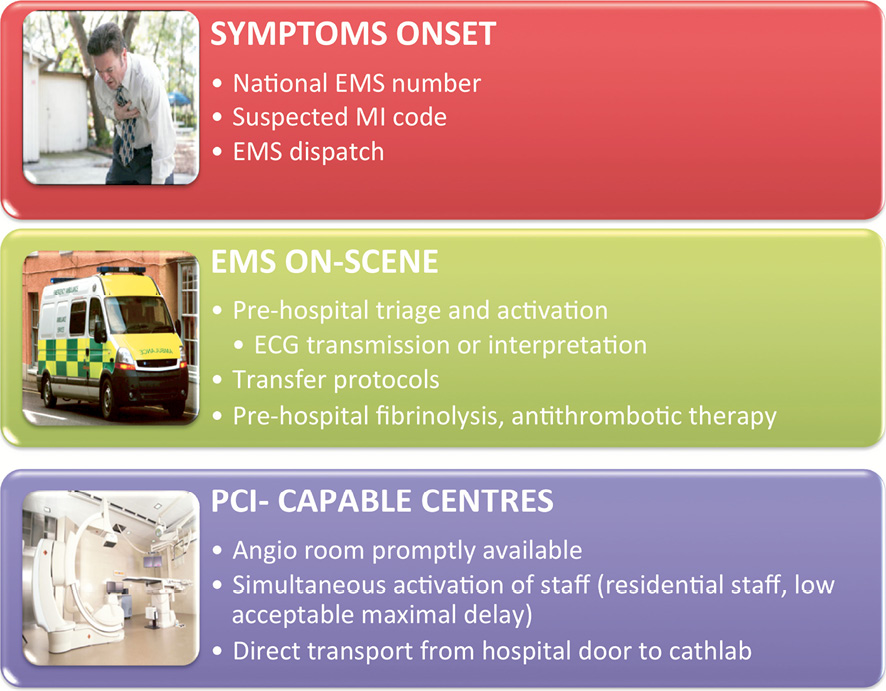

Figure 1. Various steps to accelerate prompt delivery of care in the patient’s house, the ambulance and the hospital.

Figure 2. A poster that is part of a national UK campaign to promote awareness of the importance to call 999 (unified number for emergencies) in case of chest pain.

Implementation of a well-functioning network based on pre-hospital diagnosis and fast transport to the closest available primary PCI capable centre

The process of integration between EMS and 24/7 hospitals to provide seamless delivery of care throughout a geographical area irrespective of the time of day or the day of the week was already strongly advocated in the 2008 STEMI Guidelines6 (Figure 3). This point has acquired the dignity of a specific recommendation, though only in the 2010 ESC Myocardial Revascularisation Guidelines13 and in the latest update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI STEMI guidelines14. Again a Class 1 Level of Evidence A was indicated, based on large series showing how individual changes in service organisation have impacted on morbidity and mortality. The principle is the identification of a geographical area where delivery of care for STEMI patients is provided by a single EMS system connected to well identified 24/7 primary centres. The practical application of this recommendation reveals enormous differences from country to country and region to region in terms of the size of population served, the organisation of EMS service and modalities offered by the primary angioplasty service.

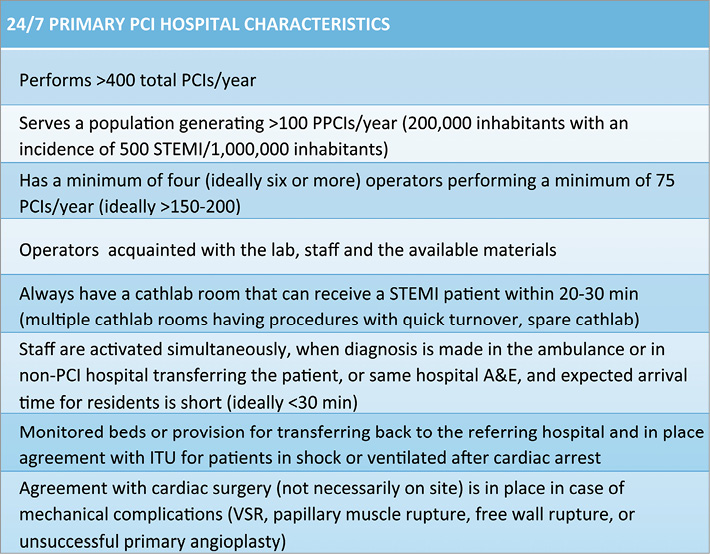

Figure 3. Optimal characteristics of a primary PCI centre.

FIRST MEDICAL CONTACT

An unified telephone number for emergency calls with an operator constantly available and competent to identify symptoms possibly related to acute myocardial infarction is the first essential requirement for timely delivery of PPCI. In Europe there is large variability in the education of the public to use such emergency services which is crucial to ensuring the smoothest and most rapid access to primary angioplasty. Occasionally patients rely on their GP and waste precious time waiting for him to be available to give advice or come to see them. More often, relatives or neighbours believe that by bringing the patient directly to A&E they may speed up diagnosis and treatment. This is not only a dangerous exercise because of the possible complications arising on route, but also hardly the best way to get the full attention of overcommitted staff in crowded A&E immediately and certainly bound to lead to delays when compared to the “ideal” path described below. The operator on the line will probably have the most difficult job in the many steps leading to a successful recanalisation: they must identify from the broken voice of a moved relative or from the words of an old patient trying to minimise the severity of his/her symptoms to the outside world the symptoms of an acute cardiac ischaemic syndrome. Constrictive chest pain with classical irradiation lasting more than 10 minutes is not the way symptoms always manifest. As shown in the article by Chieffo et al15, old women often only complain of the dyspnoea secondary to left ventricular failure and a significant number of patients have pain limited to the jaw or the epigastrium and/or profuse vomiting and diaphoresis. All these symptoms, especially when they develop in a patient in an age group at risk or in a patient with clear risk factors for CAD or with known cardiac pathology, should trigger the dispatch of an ambulance with the equipment and personnel able to perform and interpret/transmit an ECG, perform resuscitation, transfer him/her if needed to the closest primary PCI centre available, not stopping in the A&E but bringing the patient directly to the cathlab.

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SYSTEM

A subsequent chapter (Goldstein et al, this issue EuroIntervention) deals with the monumental task of the organisation of an efficient yet affordable emergency system. The guidelines stress the word “integration” which means that the intensive care specialists, nurses and drivers of the ambulance offering the first physical contact with a doctor or a paramedic after the phone call, should act as if they are working as part of a team involved in a very special diagnosis and treatment, facing one of the relatively few medical emergencies where a timely and appropriate treatment can make the difference between life and death. After having checked vital signs and pressure, when there is suspicion of a STEMI, the first priority is that an ECG should be done immediately and an interpretation obtained either directly by the ambulance personnel using clear thresholds of abnormality to trigger a primary PCI call, or via teletransmission to a dedicated specialist who will give feedback. There is more than one way of fulfilling this task. There are advantages to having an expert central operator coordinating the entire metropolitan area because he/she is aware of any possible unusual circumstances (road blocks, unavailability of the closest centre engaged in other calls) and may be able to suggest transfer to a different primary PCI centre. If the ambulance personnel have appropriate background knowledge, attendance at a well-structured training course on ECG interpretation targeted at the recognition of ST-segment elevation is a simple but appealing alternative and ensures the full attention of the ambulance crew towards this demanding choice. The experience in London has been that courses organised and repeated in the main PPCI hospitals have achieved their educational goal in helping to create the team approach and the push for the expertise these sick patients desperately need. A correct STEMI diagnosis of 94%, as achieved in London, is even more valuable when you consider that most of the other diagnoses (pericarditis, aortic dissection, etc.) still require urgent cardiological input. Besides pain control, many other treatments can be started in spacious modern well-equipped ambulances (provided protocols are well defined and the ambulance personnel are authorised to administer drugs). While nobody will argue about aspirin, decisions on the association of clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor and the use of pre-hospital thrombolysis when the anticipated delay is greater than two hours are obviously dependent on the duration of the transfer.

24/7 PRIMARY ANGIOPLASTY HOSPITAL

In principle, the population served must be sufficient to maintain the competency of the primary angioplasty centre. The absolute number is as important as the annual incidence of STEMI. There has been a progressive, and at times rapid, decrease in the incidence of STEMI attributed to better control of risk factors16,17. The decline of STEMI is quite a recent phenomenon and is probably related to the almost complete disappearance of the smoking habit in the high-risk groups in some European countries. Early recognition and treatment of new onset angina and NSTEMI are probably equally responsible but more difficult to quantify. Epidemiology of ACS is outside the scope of this paper but it is important to realise that these rapid changes require equally rapid adjustments. A gross estimate of 1,000 STEMI per million inhabitants was initially used as the average European prevalence to set the goal of the Stent for Life Initiative to offer primary angioplasty to at least 600 patients out of a million inhabitants served. This estimate is probably applicable only in some Eastern European countries, such as Ukraine or Russia, while even Northern European countries with a historically very high prevalence of CAD see only pockets of epidemics in more deprived areas while densely populated regions, such as South East England, are down to 500-600 STEMI cases/million/year. The rapid rise of obesity and diabetes limits the contraction of CAD and determines a change in the groups at risk, with women >70 years old becoming a more frequent target. Assuming an average STEMI population of 500 patients/million inhabitants, which is probably closer to the current incidence in many European countries, a single hospital providing service should not have fewer than 250-300,000 inhabitants in the served territory, barely able to provide 125-150 STEMI cases per year in some lucky areas of Southern Europe, such as Catalonia or some regions in Southern France. In rural or mountainous areas lower numbers can be considered as an acceptable choice. The ESC Guidelines do not indicate minimum numbers to maintain the competency of hospital and operators: this is probably a reflection of the extreme geographical variations across Europe which make it difficult to set meaningful thresholds13. The US ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines14 are of help but their targets are also very loose, with a minimum of 36 primary PCI/year to maintain competency as a centre. More importantly, they reaffirm that a primary PCI centre should have a reasonable volume of at least 400 PCIs/year with each operator performing a minimum of 75 PCIs/year. These are numbers nobody can argue with: a PCI centre with a volume below 400 cases/year makes no sense economically and is unlikely to offer adequate safety to patients when its personnel is exposed to an average of <8 PCIs/week, especially when the patient in question has an occluded artery that requires rapid recanalisation and is prone to arrhythmias and haemodynamic complications. Also, the number per operator of 75 PCIs/year (all PCIs, not only primary angioplasties) fits well with these calculations because you need a minimum of four to six operators to maintain a sustainable rota and 400-450 PCIs are sufficient to maintain this level if evenly split among the operators. If this is a meaningful general rule, exceptions have to be accepted and sometimes encouraged. The operators’ and possibly the paramedics’ competency can be maintained performing angioplasties in a different centre and one may accept a centre with a suboptimal number of 75-100 primary angioplasties/year if this is the only solution to ensure a timely offer of primary angioplasty in a homogeneous, sufficiently remote region and if this is compatible with the economic resources available for the health system. However, where possible, and this includes all the urban/metropolitan areas of Europe and probably two thirds of its population, there should be a move in the opposite direction to encourage the development of large primary angioplasty hubs with 300-500 patients/year. Evidently, there are no possible randomised trials comparing outcomes in low-volume and high-volume centres but all data coming from matched comparisons suggest success increases and complications fall in larger-volume centres. Obviously there is an inherent cost in maintaining an on-call service which is relatively inactive and this also plays a role in suggesting limiting the number of active primary PCI centres. There are challenges too in running high-volume centres smoothly. An impersonal service, where the operator is seen only during the acute treatment and not thereafter, and occasional excessive pressure to re-transfer or discharge the patient are potential drawbacks to consider. Much more difficult to accept is that the hard work of the EMS in bringing the patient speedily for primary angioplasty is wasted as a result of unacceptable delays in accessing the cathlab because there may be several simultaneous cases of primary angioplasty, a problem likely to occur especially at nights or during weekends if only one lab is used for primary angioplasty. A good balance can be maintained when various centres are active within the same metropolitan area and there is a central allocation unit able to allocate patients to the nearest hospital with a cathlab available to begin angioplasty immediately. There is great creativity in the way the primary angioplasty service is organised across Europe and the solutions are more often a compromise to satisfy all of the hospitals involved, not necessarily offering the most efficient and especially the most cost-efficient solution. In most European cities, all centres able to offer a round-the-clock service are allowed to offer primary angioplasty. The advantage is that ambulances are spoilt for choice and can shorten the drive to the hospital and the competition creates an incentive to raise standards; the disadvantage is that this often drives numbers below the minimum acceptable figures indicated above, a solution possibly acceptable in remote areas but not in the heart of a large city. Rotation of the hospitals on call for providing service is a possible alternative to maintain all hospitals involved, but is applicable only when the hospitals in question are strategically placed to meet the needs of the population and does not necessarily solve the problem of insufficient experience inherent in some of the participating centres. In order to keep a 24/7 service active, centres may need to attract operators not routinely working in the hospital, which may create difficulties dealing with acute cases in a foreign environment.

PROVISIONS AFTER ANGIOPLASTY

Primary angioplasty has drastically changed the treatment and prognosis of STEMI patients. The risks of acute arrhythmias and late ventricular tachycardia, mechanical complications, pericarditis and Dressler’s syndrome, haemodynamic compromise, recurrence of angina or reocclusion have all become rare events. Patient triage is performed during primary angioplasty and patients with multivessel disease are identified and scheduled for further treatment. The use of the radial approach and the elimination of the most aggressive antithrombotic and antiplatelet cocktails, substituted by weight-adjusted doses of less dangerous drugs, potentially allow rapid transfer after PPCI. Transfer is an absolute must in some units with very limited bed capacity. Transfer can be positive when it offers access to departments where the patient completes uptitration of beta-blockers and ACE-inhibitors, and receives detailed instructions on diet, pressure and cholesterol control, and the importance of physical activity. Transfer can help to balance patient flow, compensating hospitals that have accepted not to promote PPCI facilities because they are redundant for the territory in question or that have transferred the patient after having performed diagnosis. Conversely, staying in the same unit where angioplasty was performed, speaking with the operator, receiving reinforcement messages on the importance of double antiplatelet treatment can work equally well or better if the situation allows. The important message to convey is that the stent is only the first of a series of measures to implement in order to transform the risk profile. Again, multiple models have been developed, but it is essential that the patient should not be transformed into a postal package to be moved when and where convenient but that the patient’s wellbeing should remain the centre of daily decision.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.