Abstract

The UK had previously established a comprehensive strategy for in-hospital nurse-led thrombolysis for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, with a growing use of pre-hospital thrombolysis by paramedical staff in the ambulance services. The National Infarct Angioplasty Project was sponsored by the government and examined the introduction of primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty (PPCI) in a variety of urban, rural and mixed communities. The project found that PPCI could be delivered within acceptable timelines, would be cost-effective, and could be delivered to the majority of the population. A project was therefore undertaken in England to transform services. There has been a rapid change and by 2012/13 over 95% of eligible patients received PPCI. Survival of patients with STEMI has improved over time and length of stay in hospital halved. However, nearly a quarter of STEMI patients do not receive reperfusion therapy (often because of late presentation) and additional work is needed to minimise delays to treatment. There are unexplained differences between regions in numbers of PPCI procedures per million population, and there is also variance between centres in the proportion of patients who are in shock or on a ventilator. Additional research is needed to ensure a consistent approach for these sick patients, who might have the most to gain from early treatment. The national audit programmes have been instrumental in measuring the changes in strategies, monitoring performance and highlighting the associated improvements in outcomes. A new risk model is being developed to allow a more comprehensive comparison of outcomes in different hospitals.

The National Infarct Angioplasty Project (NIAP): the basis for change

Changes in healthcare systems can happen piecemeal or can be managed in a coordinated fashion. Following publication of the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease in 2000 a national reperfusion strategy for England and Wales was adopted, focusing on prompt and comprehensive delivery of thrombolysis for all eligible patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)1. However, following early experience and published evidence of the clinical benefits of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI)2-5, centres in the UK began changing the care they provided to their local populations. In some cases PPCI was provided only to patients with a contraindication to thrombolysis or for those in cardiogenic shock, but with a growing use in other patients. This was challenging to healthcare commissioners. While some argued that PPCI should become the default treatment for all STEMI, others believed that the UK’s experience in providing timely nurse-led thrombolysis on arrival at hospital and the increasing provision of paramedic-initiated pre-hospital thrombolysis made the benefits uncertain. The Prime Minister’s Development Unit and the Department of Health (DoH) agreed to support the National Infarct Angioplasty Project (NIAP) in association with the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS) and the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS). The project has been described in more detail elsewhere6.

In brief, a Working Group was established which included all relevant stakeholders (including ambulance services). A specific database was developed adding a number of key variables to the data sets already used by the BCIS (which collects data on all patients undergoing PCI in the UK) and the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) that collects data on patients suffering acute myocardial infarction in England and Wales7,8. Seven PCI centres representing varying models of service delivery to urban, rural and mixed communities were allocated extra funds for data collection, but not service delivery. Data were also collected from surrounding referral centres to ensure that patients treated with thrombolysis were included. All patients presenting with STEMI were included over a one-year period with one year of follow-up. Interim and final reports were produced for the DoH and a cost-effectiveness analysis was undertaken9-13.

The project found that PPCI could be delivered with acceptable treatment times and that, as long as treatment delays were minimised, PPCI was cost-effective (albeit more expensive than thrombolysis) in an English healthcare setting. These findings were consistent with previous studies on cost-effectiveness of PPCI14-16. PPCI was associated with fewer complications, better outcomes and a shorter length of hospital stay. The service was evaluated favourably by patients. Shortest treatment times were achieved following direct admission of patients to the cardiac catheter laboratory, whereas admission via an Accident and Emergency Department or even via Coronary Care Units created avoidable delays. Initial presentation of patients to a hospital without PPCI capability with subsequent transfer to a PPCI centre created the longest delays. Using isochrone mapping techniques it was estimated that 95% of the UK population lived sufficiently close to a PCI centre for PPCI to become the preferred treatment and it was believed that a national roll-out could be achieved within three years.

However, there remained considerable challenges to be overcome to provide such a service redesign on a national scale, ensuring continuously available (24/7) on-call PPCI services and deciding which centres should be designated as “Heart Attack Centres”. Chosen centres would be required to deal with a regional referral base and to have in place appropriate clinical pathways to enable non-PCI district hospitals to participate in clinical follow-up and continuing care of patients – an integration of “patient-centred” care across different hospitals. There was the additional need to persuade Accident & Emergency Department personnel and non-interventional cardiologists to accept a major reconfiguration of services to achieve potential improvements in outcomes. One observation of NIAP was the considerable demographic differences between participating hospitals in the patients treated, especially with regard to age, ethnicity and key risk factors such as diabetes. This was not a result of treatment bias, but rather a reflection of differences in local demographics. Such differences may influence unadjusted outcomes following reperfusion.

Implementation of a national service

The NIAP demonstrated the importance of designing a national service that maximised the potential for patients diagnosed with STEMI being transported directly to a cardiac catheter laboratory. This had already been highlighted by European colleagues and was reinforced in subsequent studies17,18. In the UK, there is a national publicly-funded ambulance service, staffed by trained paramedics rather than physicians. The previous development of pre-hospital thrombolysis services had already necessitated training of paramedics in the performance and interpretation of 12-lead electrocardiograms and in the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes. However, a great deal of regional work was needed to implement changes in systems. It was recognised that the hospital services needed a central point of contact to activate the “PPCI pathway”. There needed to be the capacity to activate the pathway at any time, by whichever service had made the diagnosis, so as to provide immediate care for patients diagnosed in the community, those who self-presented to hospital, and those who suffered a STEMI while already in hospital for another reason (e.g., NSTEMI ACS or a postoperative event). Where PPCI services could not be established, or when they could not be offered in a timely fashion, pre-hospital thrombolysis remained the preferred strategy, with the subsequent referral of patients for an invasive strategy, either rescue angioplasty or angiography and PCI if indicated after successful thrombolysis.

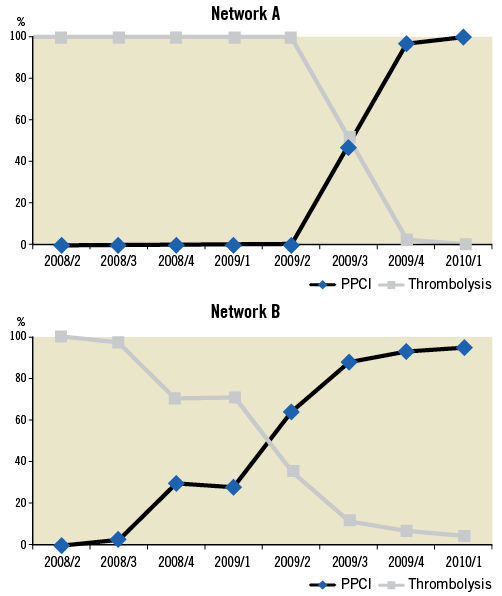

The ability to change whole systems of care in order to introduce a new treatment strategy was helped by the existence of Regional Cardiac Networks, which provided a forum for discussion between local healthcare commissioners and those delivering primary, secondary and tertiary care services. These were coordinated by a DoH organisation called NHS Improvement which promoted the development and sharing of best practice and allowed for cross-boundary discussions. A National Clinical Lead for PPCI (J.M. McLenachan) was appointed in 2008 who, working with a National Improvement Lead, advised each region on how best to change from the current service to one providing PPCI as the default treatment. Many hurdles were overcome during the subsequent three years. Some regions implemented slow but progressive evolutionary change, rolling out the service from one area to another over time (e.g., Network B, Figure 1). Other regions made an almost overnight revolutionary change from thrombolysis to PPCI, having worked hard to develop a consensus prior to implementation. The project was given wide coverage at national society meetings, in national and local media, and a guidance document was published by NHS Improvement to help the transition19.

Figure 1. Reperfusion therapy given: change from thrombolysis to PPCI in different Cardiac Networks.

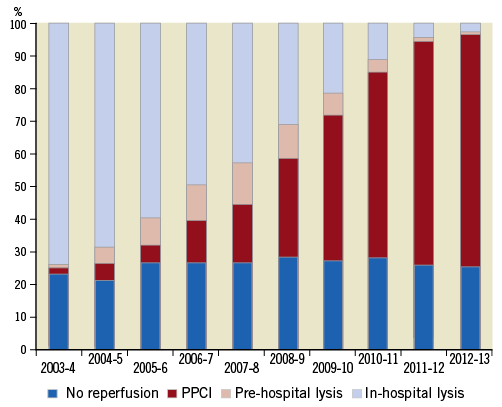

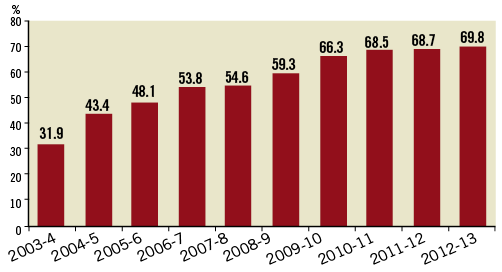

A fundamental shift in direction was achieved. This has been supported and monitored by the national clinical audit programmes. Figure 2 shows the use of reperfusion therapy in STEMI between 2003 and 201220.

Figure 2. Management of patients with STEMI in England and Wales (data from MINAP)20.

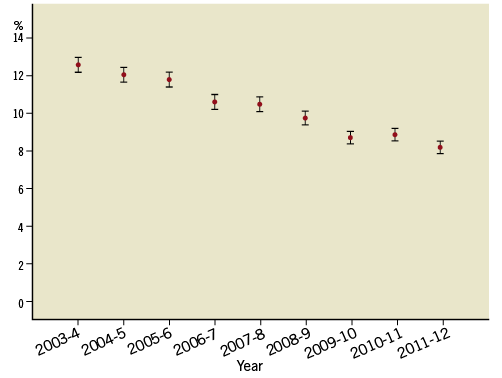

This shows a remarkable change compared with a previous European survey21, with PPCI becoming the dominant reperfusion management by 2009/10 and now being almost the exclusive treatment provided in the UK. Interestingly, the proportion of patients who receive no reperfusion therapy remains at around 25%. Moreover, the introduction of PPCI has been associated with a substantial fall in the median length of stay in hospital for patients with STEMI: six days (interquartile range [IQR] 4-10) in 2003/4 vs. three days (IQR 2-5) in 2012/2013. In parallel with this change, the survival of patients with STEMI has improved over time (Figure 3)22,23.

Figure 3. 30-day mortality (with 95% CI around the point estimate within each year) for all patients with STEMI in England and Wales (data from MINAP)23.

In spite of these changes there remain some unresolved issues.

A continuing role for thrombolysis?

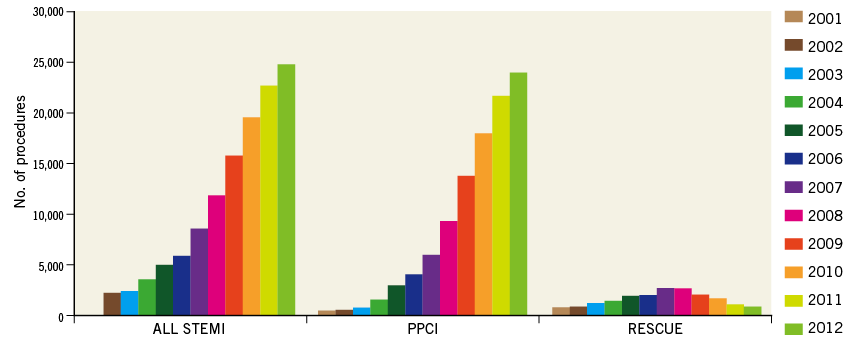

There has been some debate about the interpretation of the evidence base underlying national and international guidelines. This has concerned analysis of the PPCI-related delay (i.e., the delay between the start of a PPCI procedure and the time when the same patient might have been treated with thrombolysis). Although there has been debate about the separate times when patients first call for help or present themselves and the time of “first medical contact”, the impetus is to minimise treatment delays24-27. In the UK, the most recent guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that PPCI should be used if it can be delivered within 120 minutes of when thrombolysis could have been started28. Previous reports have suggested an interval between a call for help and the start of thrombolysis of about 30 minutes, and so this has been translated into a requirement to provide PPCI if it can be delivered within 150 minutes from the first call. The Strategic Reperfusion Early After Myocardial Infarction (STREAM) trial compared thrombolysis (with either rescue PCI or follow-on angiography) with PPCI in patients presenting within three hours who could not receive PPCI within an hour29. Some have interpreted the results of STREAM as supporting the use of a “pharmacoinvasive” approach for these patients, whereas others have suggested that there is no clear advantage of thrombolysis in this cohort and that, as it may be associated with an increased risk of stroke, it is pragmatically simpler and safer to have a single policy of PPCI for all eligible patients. In the UK, most patients lived close enough to a centre that could provide PPCI and, in those remaining rural regions, where travel times were long, the development of new PPCI services has meant that only a small proportion of patients now receive thrombolysis. For those who do not receive PPCI and who are treated with either thrombolysis or no reperfusion treatment, there has been a gradual increase in the subsequent use of early angiography (Figure 4), but unsurprisingly the absolute number of patients undergoing rescue PCI has fallen over time (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Growth in the use of angiography for patients receiving thrombolysis or who receive no reperfusion therapy for STEMI (data from MINAP)20.

Figure 5. Growth in PPCI and fall in use of rescue PCI over time (data from BCIS)30.

Patients who do not receive reperfusion therapy

As mentioned above, the shift from thrombolysis to PPCI has not changed the proportion of patients who receive no reperfusion therapy for STEMI (Figure 2). This is an area undergoing additional work, to determine whether there are missed opportunities. Most of these patients do not receive treatment because of a significantly delayed presentation or major contraindications to reperfusion treatment. The NICE guidelines recommend treatment within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms, and PPCI should also be considered for those who present later than this if there is evidence of continuing ischaemia28. In some patients reperfusion therapy is deemed inappropriate because of comorbidities such as disseminated cancer or dementia, or additional medical problems such as active bleeding. A few patients are deemed too sick to be likely to gain benefit. Some patients refuse treatment. The use of angiography has also identified a number of patient groups who do not go on to receive immediate reperfusion therapy, for example those without an occluded vessel, those where a small side branch is occluded, and those with a different pathogenic mechanism (e.g., Takotsubo syndrome). These patients will all be classified as having “no reperfusion” even though reperfusion therapy is deemed unnecessary. Nevertheless, there are some patients where there are inappropriate delays in diagnosis or additional delays to treatment, and so a continuous review of all such patients is recommended to ensure all appropriate patients receive treatment. Additional work is being done to track fully the entire cohort of patients for whom the clinical pathway is activated but where PPCI is not undertaken.

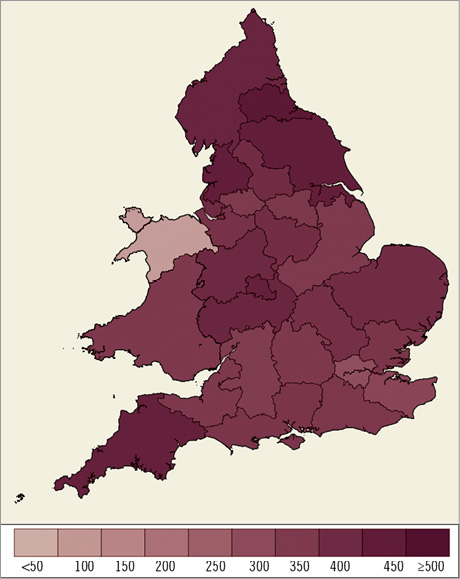

Geographical variance in treatment

Although there has been a trend towards a more consistent level of reperfusion across the country, the MINAP has reported a continuing variance across the country that is poorly understood (Figure 6). National figures suggest that the incidence of STEMI in England and Wales is about 500/million population but it is known that the incidence is higher in some parts of the country (e.g., the north) than others. Further research is needed to understand these differences, partly to identify areas where greater work is needed on primary and secondary preventive strategies to help reduce the number of cases, but also to identify areas where additional change is needed to ensure a more consistent continuous availability of best care.

Figure 6. Number of PPCIs per million population for local area teams 2012/13 (reproduced with permission from MINAP)20.

Challenges for commissioners

Following the last General Election in the UK in 2010, the administration of the NHS changed. Each country now has devolved responsibility for the commissioning of health care. In England, clinical advisors have been asked to develop a service specification for PPCI centres, and they have supported the European Society of Cardiology guidelines which recommend that all PPCI centres should be 24/7 centres24. However, in the implementation phase to roll out PPCI in the country, regions developed different models. Some used only 24/7 centres, while others allowed some centres performing daytime-only PCI to perform PPCI with a change in local protocol for direct referral to a 24/7 centre out-of-hours. There are insufficient data available to determine whether outcomes are improved or worsened by such models, with several competing factors. On the one hand, local delivery of PPCI during ordinary working hours may reduce CTB and DTB times, as long as those centres are organised appropriately to minimise these times, but then patients treated out-of-hours are potentially disadvantaged by longer treatment times. Larger centres may have a better infrastructure to deal with the sickest patients (those in shock or on a ventilator). Previous volume-outcomes studies in PCI suggest better outcomes in larger centres and better outcomes with more experienced operators31-33, but there are no studies in contemporary PCI, and it is difficult to determine a precise minimum level of activity where outcomes might be jeopardised. These issues have been recognised in the latest guidance from NICE28. Additional research is needed to help shape policy decisions.

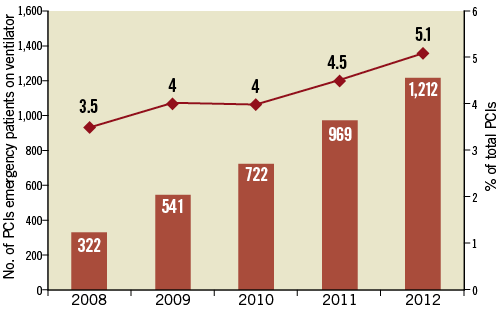

Treatment of patients with cardiogenic shock and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

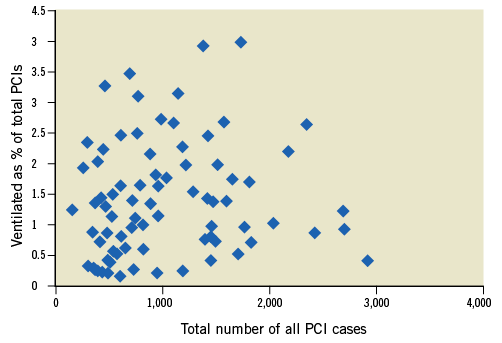

The NICE guidance in 2013 also reviewed the evidence for PPCI in the setting of cardiogenic shock and those who had suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest28. Although the level of evidence was not strong, the guidelines recommended that urgent angiography and follow-on PPCI should be offered to those in shock who present within 12 hours and should also be considered for those who develop shock beyond 12 hours. For those who remained unconscious after a cardiac arrest, the guidelines group noted a lack of appropriate evidence, recommended additional research for this cohort, but concluded that there was no reason to treat these patients differently from other patients suffering STEMI: that the decision to offer angiography should be influenced by criteria other than the unconscious state. There has been a gradual rise in the number of patients treated whilst on a ventilator but data from BCIS have revealed considerable variation in the proportion of patients who are treated for shock and after an out-of-hospital arrest (Figure 7, Figure 8). This variation seems inexplicable by epidemiological differences, and points to varying hospital thresholds for treating these patients.

Figure 7. Growth in PCI for patients on a ventilator (data from BCIS)30.

Figure 8. Variation in number of ventilated patients treated between centres (2012 data from BCIS)30.

National audit of systems of care

Both BCIS and MINAP provide annual public reports and have collaborated to provide feedback systems to every PCI centre on a range of measures. Most important amongst these are the measurement of call-to-balloon (CTB) times and the door-to-balloon (DTB) times for those centres providing the PPCI service. In addition, a separate report is provided for the time delay from presentation at the first hospital for those who are transferred for PPCI. The hope is that the continuous feedback of these data provides the impetus for optimising the care pathway and providing slicker and faster treatment. Audit becoming an important facet of quality improvement, initial targets were for 75% of all patients receiving PPCI to have a CTB time of less than 150 minutes, and for 75% to have a PPCI centre DTB time of less than 90 minutes. The national audit has revealed that the best centres have a median DTB time of less than 30 minutes, and so there are internal discussions to determine whether the national targets should be tightened to try to ensure best practice across the country. Further research is needed to determine whether such national targets will improve outcomes significantly or whether there is a plateau in what might be achieved on a national scale.

In England, there is now a demand that the results of individual operators be made publicly available. Currently, we have been utilising the North West Quality Improvement Programme risk model to compare actual with predicted results, looking at a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events up to the point of hospital discharge34. This relies on the accuracy and completeness of data regarding these adverse outcomes that are collected by each hospital. Given the need to recalibrate this model to fit contemporary PCI, and a desire for independent validation of outcome data, BCIS decided there was a potential advantage in developing a risk model that only assessed mortality because all deaths can be identified from nationally collected statistics –this work continues.

Techniques used in PPCI

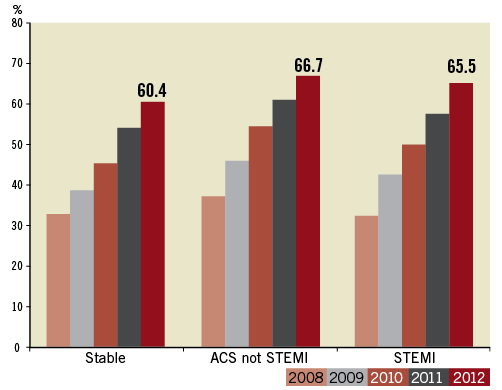

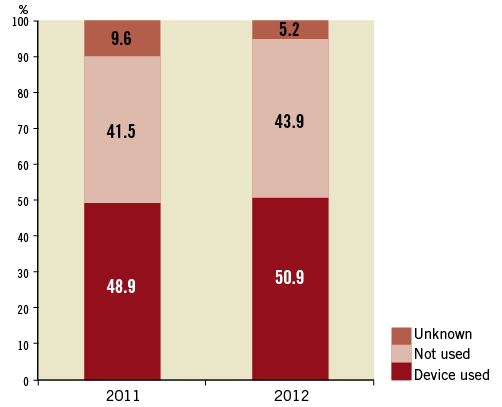

As concerns about the safety of drug-eluting stents have diminished, especially with the latest generation of devices, there has been a gradual increase in their utilisation, with nearly 70% use in PPCI in 2012. The NICE guideline reviewed the evidence on the use of radial access28. Although there is evidence to suggest better outcomes and less bleeding, NICE recommended additional research, and the guidance stated that the radial (in preference to femoral) arterial access should be considered. BCIS has recorded a gradual increase in the use of the radial artery approach for PPCI (Figure 9) although there is still considerable variation among centres. Similarly, NICE reviewed the use of thrombus extraction devices. The guideline group felt that there was some evidence of benefit and little evidence of harm, but that the overall benefits were uncertain28. This uncertainty remains after the early results from the Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Scandinavia (TASTE) trial35. The NICE recommendation is that a thrombus extraction device should not be used routinely but could be considered. In spite of continuing uncertainties, cardiologists have performed thrombus extraction in a relatively large proportion of patients (Figure 10). Longer-term outcomes from TASTE and the future results of other trials such as the Thrombectomy with PCI versus PCI alone in patients with STEMI undergoing PPCI (TOTAL) trial may further influence usage36.

Figure 9. Growth in use of the radial approach in PPCI (data from BCIS)30.

Figure 10. Use of thrombus extraction devices during PPCI in the UK (data from BCIS)30.

Adjunctive pharmacology in PPCI

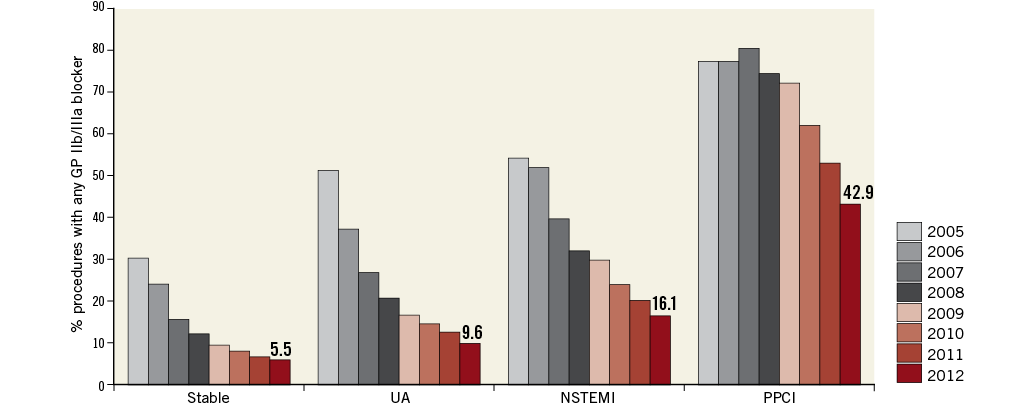

In line with trial results and national and international guidelines, there has been a growth in the use of prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients undergoing PPCI, but there are many centres still routinely using clopidogrel. The use of bivalirudin has increased and the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors has reduced (Figure 11). There is, however, considerable variation among centres. The impact of the How Effective are Antithrombotic Therapies in Primary PCI (HEAT-PPCI) trial on choice of therapy has yet to be determined37. The variation in use suggests that there are different interpretations around the evidence base for each class of drug. Additional research is needed to determine whether one strategy is better than another, or whether we now have a number of equally effective strategies, in which case choice will be determined predominantly by cost.

Figure 11. Fall in use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in PCI in the UK (data from BCIS)30.

Continuing need for secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation

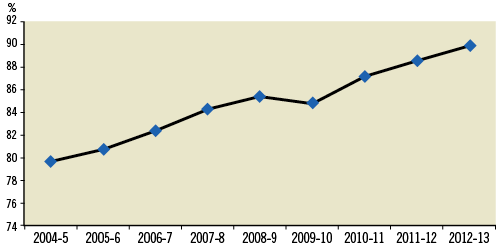

Concern was expressed in the NIAP evaluation that the shorter lengths of stay associated with PPCI would result in fewer patients starting appropriate secondary preventive medications during the index admission, and that transfer back to local primary and secondary care services might result in a failure to up-titrate doses of drugs. Much work has occurred at regional level to ensure that these opportunities would not be lost, and indeed evidence from MINAP suggests that there has been a continuing improvement in this aspect of care for all patients suffering a heart attack (Figure 12). Although there are continuing debates about the impact of cardiac rehabilitation on mortality, there is good evidence for a reduction in anxiety levels, a reduction in hospital readmissions and a more rapid return to normal life. There was a similar concern that patients would miss out on a referral to a cardiac rehabilitation service following the introduction of PPCI. The NICE guidance recommends appropriate secondary prevention approaches including cardiac rehabilitation for all patients whether they have received reperfusion therapy or not38,39.

Figure 12. Use of appropriate secondary preventive medication following a heart attack (excludes deaths, refusals, contraindicated therapy and transfers) (data from MINAP)20.

Conclusions

The NIAP was a collaborative project between the UK government and national professional societies to examine the feasibility of a change from thrombolysis to PPCI as the preferred treatment for patients with STEMI. It showed that a wholescale change could be supported and was likely to be cost-effective. A national implementation process was put in place to change strategies. Given the challenges faced, the speed of implementation that occurred when government, having reviewed evidence and feasibility, supported clinical leaders and practising clinicians is perhaps remarkable. More than 95% of patients who are eligible are now treated with PPCI, with thrombolysis being used in a small number of patients where PPCI cannot be delivered within the nationally agreed timescales. It is likely that this change has had a significant beneficial impact on outcomes for patients.

Continuous monitoring of activity has shown that there remains room for improvement, with too much inconsistency in treatment times. Feedback mechanisms are in place and it is hoped that these will have a favourable impact on performance. The national data collection exercise also tracks the use of new adjunctive pharmacotherapies. However, there are continuing uncertainties about many aspects of care, and additional research is needed, in particular, to ensure that patients at the very highest end of the spectrum of risk are treated in a consistent manner. These include patients with cardiogenic shock, those who have suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and those who require ventilation prior to PPCI. A deeper understanding is required of volume-outcomes relationships in contemporary PPCI and the impact of different models of service (especially 24/7 vs. non-24/7). This will further influence national and regional policies for service provision.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.