Abstract

In 2004 in the United Kingdom (UK), the infrastructural and organisational changes required for implementation of primary PCI for treatment of STEMI were unclear, and the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of a changed reperfusion strategy had not been tested. In addition, any proposed change was to be made against the background of a previously successful in-hospital thrombolysis strategy, with plans for greater use of pre-hospital administration.

A prospective study (the “National Infarct Angioplasty Project - NIAP”) was set up to collect information on all patients presenting with STEMI in selected regions in the UK over a one year period (April 2005 - March 2006). The key findings from the NIAP project included that PPCI could be delivered within acceptable treatment times in a variety of geographical settings and that the shortest treatment times were achieved with direct admission to a PPCI-capable cardiac catheter laboratory.

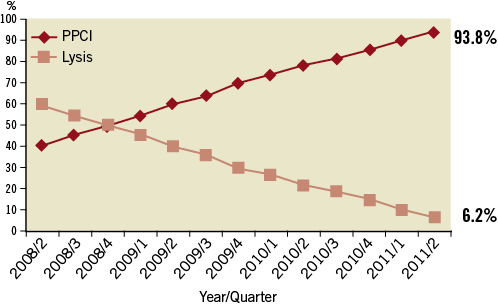

The transformation from a dominant lytic strategy to one of PPCI across the UK was achieved both swiftly and consistently with the help of 28 cardiac networks. By the second quarter of 2011, 94% of those STEMI patients in England who received reperfusion treatment were being treated by PPCI compared with 46% during the third quarter of 2008.

Abbreviations

BCIS: British Cardiovascular Intervention Society

BCS: British Cardiovascular Society

CHD: coronary heart disease

CTB: call-to-balloon

DoH: Department of Health

DTB: door-to-balloon time

EAPCI: European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions

ECG: electrocardiogram

ESC: European Society of Cardiology

MINAP: Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project

NHS: National Health Service

NIAP: National Infarct Angioplasty Project

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

PHT: pre-hospital thrombolysis

PPCI: primary PCI

SDO: Service Delivery and Organisation

STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction

UK: United Kingdom

24/7: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) had been used by individual centres for the treatment of acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) for many years, but it was not until the DANAMI-2 and PRAGUE-1 & 2 trials (and the ensuing meta-analysis by Keeley et al) that primary PCI (PPCI) became more widely acknowledged as the preferred method of reperfusion1-4. Trial evidence had demonstrated the benefits of PPCI over using thrombolysis, but in the UK the infrastructural and organisational changes required for implementation were unclear, and the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of a changed reperfusion strategy had not been tested. In addition, any proposed change was to be made against the background of a previously successful in-hospital thrombolysis strategy, with plans for greater use of pre-hospital administration5,6.

By 2004, London had already changed its reperfusion strategy for STEMI and was undertaking PPCI 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (24/7), but outside the capital city provision of PPCI was patchy. The Department of Health (DoH) agreed to allocate £1m towards a prospective study (the “National Infarct Angioplasty Project - NIAP”) aimed at investigating the feasibility of national roll-out of PPCI services. At the same time, the National Health Service (NHS) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme awarded a grant to the School for Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, to evaluate issues of cost-effectiveness, patient experience and feedback from the workforce of centres delivering PPCI.

The National Infarct Angioplasty Pilot Project

In 2004, a Working Group was set up with representation from the DoH, the British Cardiovascular Society (BCS), the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS), the NHS Coronary Heart Disease Collaborative, the ambulance services, and a health economist. A dataset was produced, based on the already available national datasets of the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) and BCIS, and a selection process resulted in seven centres being asked to participate in the project (Appendix), reflecting different geographical areas of England. Central funding was provided to participating centres for data collection, but the costs of service delivery were met locally. Centres were selected to represent a number of different service delivery models, ranging from urban, to rural, to mixed populations, and to include PPCI services which required inter-hospital transfers for some cases. The aim was to collect information on all patients presenting with STEMI in the designated regions over a one-year period (April 2005 - March 2006) and there was an additional minimum of one-year follow-up. Patients treated with thrombolysis at additional designated hospitals were also included to ensure that contemporary data on a cohort treated with thrombolysis were available. Analysis of the data was performed in 2007 and the interim and final reports published in 2008, with subsequent publications from the University of Sheffield7-11.

Data were collected on 2,245 patients: 795 (35%) had presented to a hospital without PCI facilities, and 1,450 (65%) had presented to a PCI centre. The age range of the female patients (29% of the cohort) was 34-100 years (mean 70.5, median 72); for males it was 25-104 years (mean 61.5, median 61). These data were very similar to the demographics of the entire MINAP population (all STEMI patients in England & Wales) collected during the same time period, and so there was little suggestion of a selection bias. It was of note that there were considerable demographic differences between centres, with some serving an older population and others having a greater proportion of ethnic minorities. Of the patients presenting to the centres without PCI facilities, 58% were transferred for PPCI, 29% had thrombolysis as their primary reperfusion strategy and 13% received neither form of therapy. Of those presenting to the PCI centres, 69% received PPCI, 16% thrombolysis and 15% neither. Reasons for not providing PPCI for all patients in the PCI centres included the fact that not all centres had a 24/7 PPCI service at that time. Some did not have sufficient staff to provide the service at weekends and some centres in their early experience used thrombolysis outside of normal working hours.

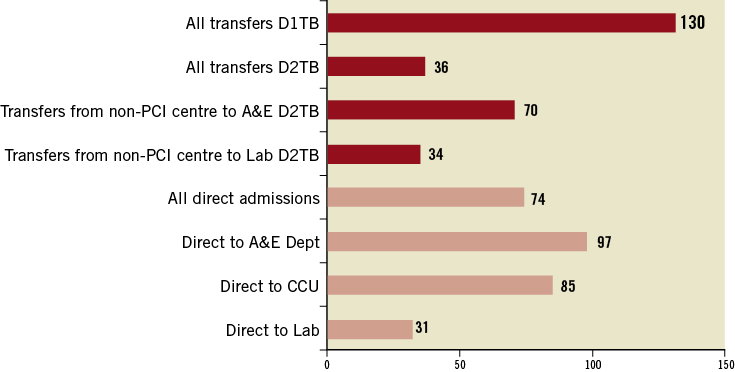

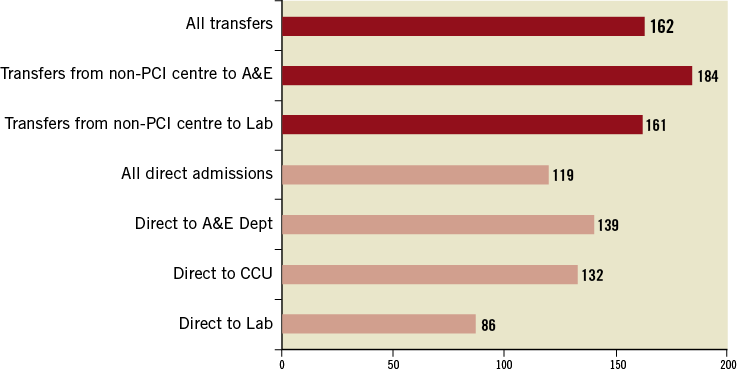

Of the 2,245 patients, 94% were out-of-hospital at the time of onset of symptoms and 80% of these were brought to hospital by ambulance. No clinical complications occurred in 93% of all ambulance journeys, and in the rest the most common problem was a ventricular arrhythmia from which all were resuscitated. The door-to-balloon (DTB) and call-to-balloon (CTB) times of those patients receiving PPCI are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. As with other experiences in Europe12,13, it quickly became clear that the optimum service for PPCI was to take patients directly to the catheter laboratories of the PPCI centres, with ambulances bypassing non-PPCI centres and also bypassing the emergency departments and coronary care units of the PPCI centres. When a target DTB time of less than 90 mins was tested, it was clear that this could only be achieved with direct admission and transfer to the catheter laboratory in PPCI-enabled centres: 98% of PPCI procedures fell within this time interval, but this dropped to less than 60% of patients if patients were delayed by being assessed in emergency departments or coronary care units first, and to less than 20% when an inter-hospital transfer was required.

Figure 1. Median door-to-balloon times (minutes) in the NIAP project7. CCU: coronary care unit; A&E: Accident & Emergency; Lab: catheter laboratory; D1TB: time from arrival at door of non-PCI centre (door 1) to balloon inflation of transferred patients; D2TB: time from arrival at door of PCI centre (door 2) to balloon inflation for transferred patients.

Figure 2. Median call-to-balloon times (minutes) in the NIAP project7. CCU: coronary care unit; A&E: Accident and Emergency; Lab: catheter laboratory.

The use of PPCI was associated with a significant reduction in the median length of hospital stay for all patients (4 days, vs. 6 days for patients treated with thrombolysis). This was seen across all age groups, and is consistent with equivalent data from the MINAP database for the same time period. PPCI services during the NIAP project were in the early stages of development, but nevertheless in-hospital mortality was in keeping with contemporary reports: PPCI 4.4%, thrombolysis 6.6%, and 16.9% for those patients not receiving any reperfusion therapy.

Although there had been previous publications on the cost-effectiveness of PPCI, these had either not been applied to a UK healthcare setting or only included short-term costs14,15. Following an analysis of cost-effectiveness in relation to timing of reperfusion based on available trial data, a similar analysis was performed using data collected in the NIAP project11,16. The conclusion from the latter study was that PPCI is cost-effective if delivered in a timely manner, but that both the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were diminished with increasing delays.

The key findings from the NIAP project were as follows7,8:

– PPCI could be delivered within acceptable treatment times in a variety of geographical settings

– The shortest treatment times were achieved with direct admission to a PPCI-capable cardiac catheter laboratory

– Longer times to treatment occurred if the patients were first assessed in an emergency department, a coronary care unit, or at a local (non- PPCI) hospital

– Longer times to treatment were associated with higher mortality rates

– PPCI was more expensive than thrombolysis but was both clinically effective and cost-effective when delivered within 120 minutes of a patient calling for professional help

– Although not a randomised trial, PPCI was associated with few complications, a low recurrence of reinfarction, a low incidence of stroke and a low mortality rate

– There was a high level of patient satisfaction with PPCI9

– Staff working in PPCI teams preferred starting with a 24/7 service at the outset rather than incremental change10.

In the evaluation of the patient and carer experiences, although most were satisfied with the delivery of the PPCI service, there were concerns about the quality of information and patient education at the point of discharge, and also concerns that patients were not being offered full cardiac rehabilitation programmes9. Multi-skilling and working across established professional boundaries were advantages in relation to developing the workforce. Auditing of the clinical pathways was a key component of successful service delivery. However, to ensure sustainability, differences in both pay and rest periods for those undertaking significant amounts of out-of-hours work would have to be addressed10.

The NIAP project concluded that the vast majority of patients presenting with STEMI in England and Wales could be treated by PPCI within appropriate treatment times. In the foreword to the final NIAP publication, a government minister commended the feasibility project and said that a faster pace of change was needed, with a rapid expansion of PPCI throughout England. The National Health Service was charged with the task of rolling PPCI out to cover 95% of the population of England within a period of three years (2009-2011) although it was accepted that there would be logistical challenges in some parts of the country. It was felt that hybrid services, those delivering PPCI in hours and thrombolysis out-of-hours, were not satisfactory and that services should be set up to perform PPCI in a timely fashion 24/7. It was also recommended that PPCI should be carried out in centres with a sufficiently high volume of procedures to maintain and develop the skills of all staff delivering the service. Where timely delivery of PPCI could not be achieved (usually due to matters of local geography), pre-hospital thrombolysis was the preferred alternative reperfusion strategy, and patients treated in this way should subsequently be investigated with coronary angiography, in keeping with the contemporary European Society of Cardiology guidelines for PCI17.

From NIAP to national implementation of PPCI - role of NHS Improvement and the Cardiac Networks

To transform reperfusion services for an entire country from one dominated by thrombolysis to one of PPCI was a major challenge. However, several of the important building blocks for an effective PPCI service were already in place in 2008. These included the following:

A STATE-FUNDED AMBULANCE SERVICE

The United Kingdom has a state-funded ambulance service. Private ambulances are rarely, if ever, used to transport acutely ill patients. Ambulances in England are staffed by highly trained paramedics, but not by doctors. Traditionally, the responsibility of the ambulance personnel has been to transport the patient to the nearest general hospital. PPCI represented a challenge because the patient had to be taken safely to the nearest PPCI centre which sometimes meant driving past one or more local hospital(s). However, the concept of specialist centres for specialist care was quickly embraced by the ambulance personnel and the public, and is now being widened to cover other emergency conditions including major trauma and stroke services.

ESTABLISHED PRE-HOSPITAL DIAGNOSIS

In the 1990s, awareness that early administration of thrombolysis was associated with better outcomes led to the organisation of pre-hospital thrombolysis (PHT) services in some parts of England and Wales. The paramedic ambulance personnel were trained in electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation, and guidelines were drawn up for the administration of fibrinolytic agents in ambulances en route to the nearest hospital. Pre-hospital diagnosis of STEMI was therefore normal clinical practice in many areas prior to the introduction of PPCI18.

A CULTURE OF NATIONAL DATA COLLECTION AND NATIONAL AUDIT

The publication of the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in 2000 set standards for the treatment of patients with CHD19. These included performance targets for the administration of fibrinolysis to ensure patients received treatment without undue delay. Targets were set for the “door-to-needle” time, this being the time interval between the arrival of the patient at the door of the emergency department and the initiation of fibrinolysis. Latterly this target time was set at 30 minutes. These times were recorded and entered into the national MINAP database which published annual results18. Other data collected included the percentage of patients presenting with myocardial infarction treated with appropriate secondary prevention therapy, such as aspirin, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and statins. The setting of standards, and the subsequent collection and publication of data for individual hospitals, brought about a marked improvement in the treatment of STEMI patients between 2000 and 2008.

NHS IMPROVEMENT AND THE CARDIAC NETWORKS

Regional cardiac networks (n=28) had developed over the preceding five to ten years, which encouraged discussions and joint working between local commissioners of healthcare and representatives from primary, secondary and tertiary services. The 28 cardiac networks (or cardiac and stroke networks) in England operate under the umbrella of the parent organisation, NHS Improvement. NHS Improvement is a national, government-funded organisation, the aims of which are “to achieve sustainable effective pathways, to share improvement resources and learning, to ensure value for money and to improve the efficiency and quality of NHS services.” Its aim was to encourage collaboration between the networks.

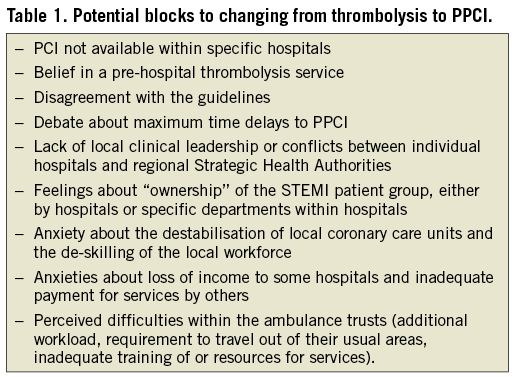

Following the announcement that PPCI would be rolled out to cover 95% of the population over a period of three years, there was discussion as to how this might be achieved. It was clear that any PPCI service had to operate 24/7. It was equally clear that for all hospitals providing a PCI service to move to a 24/7 PPCI service would be difficult and inefficient. The clinical networks were tasked with implementing the roll-out. The NHS Improvement programme appointed a National Clinical Lead and National Improvement Staff Member for PPCI, who travelled around the regions advising on how services could be implemented, taking into account the relevant local factors. A number of potential blocks to change had to be overcome (Table 1).

Timing of PPCI

The superiority of PPCI over thrombolysis is beyond doubt if the time to treatment is the same for both forms of reperfusion. However, PPCI usually involves a longer delay to treatment than thrombolysis, which is particularly the case in areas with a pre-hospital thrombolysis programme. The issue to be addressed in the setting of national guidance, therefore, was as follows: –at what time delay are the clear advantages of PPCI over thrombolysis lost? This has been the source of much debate. Initial recommendations were that PPCI should be carried out with a delay of no more than 90 minutes from first medical contact (FMC)20. In England, the time being routinely monitored is the call-to-balloon (CTB) time. The “clock” for the CTB time starts whenever the telephone call from the patient (or relative) connects with the ambulance control centre. The first contact between the patient and the paramedic will be a number of minutes later and the first contact between the patient and any doctor will occur when the patient reaches hospital. The most recent review of data published at that time suggested that PPCI remained the optimal treatment for STEMI patients provided the PCI-related delay (i.e., the delay from the time the patient would have received lysis to the time of the PCI procedure) did not exceed 80-120 minutes [21]. In the era of fibrinolysis, the target times in the UK were: call-to-needle less than 60 minutes, and door-to-needle less than 30 minutes. In setting up PPCI services, therefore, it was agreed, after much discussion, that patients should be treated by PPCI unless the CTB was likely to exceed 150 minutes. This was then introduced as a national service standard, for the purpose of assessing quality of patient care.

Transforming the clinical pathway

Different cardiac networks faced different challenges. In some rural areas, with longer transport times, decisions had to be made about whether all patients should be transferred for PPCI or whether a pre-hospital thrombolysis service should continue for those patients more than 90-100 minutes drive from the PPCI centre. In other networks, there were issues about whether some smaller hospitals should provide a limited hours PPCI service (9.00 am to 5.00 pm Monday to Friday) with out-of-hours patients travelling to the more distant centres, or whether all PPCI patients should be transferred directly to the 24/7 centre. Some issues were common to all networks:

– all networks had to develop pathways for patient referral and transfer to ensure the shortest possible CTB and DTB times

– all networks had to resolve local issues relating to 24/7 staffing of the service by medical, nursing, technical and radiography staff

– all had to reach agreement with the non-PPCI hospitals in the network about whether those patients treated by PPCI should spend their entire hospital stay in the PPCI centre or whether they should be transferred to their local hospital after their PPCI procedure.

Different networks reached different solutions. To assist each network in developing a local implementation plan, resources were provided by NHS Improvement. NHS Improvement hosted a number of national meetings that brought together the clinical leads of the 28 networks. The purpose of these meetings was to reflect on progress and to share successful experiences. NHS Improvement also published two documents to aid the networks in developing their strategy: “A Guide to Implementing Primary Angioplasty” (June 2008) and “National roll-out of Primary PCI for patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: an interim report” (September 2009)22,23. In addition, NHS Improvement provided bespoke advice to individual networks as requested and provided expert opinion to local network meetings when invited to do so. In this way, each network developed its own local implementation plan, tailored to its pre-existing infrastructure, to allow them to commission this new service in line with national strategy. Attention was also paid to the programme at the national BCS and BCIS specialist society conferences.

Importance of secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation

Primary PCI is a major step forward in the management of patients with ST-segment elevation MI. However, the speed of treatment can leave patients bewildered and confused about exactly what has happened to them24. Patients may see their heart attack as an acute event from which they have been “cured”. Access to cardiac rehabilitation services is crucial to allowing patients, and their carers, to understand that they should return to a fully productive life but to understand also that coronary artery disease is a chronic condition and that lifestyle modification and compliance with prescribed medication will greatly reduce the risk of further adverse events. A vital part of each network’s pathway, in keeping with the findings from NIAP, was to ensure that all PPCI patients were offered timely access to cardiac rehabilitation services.

Results

THE NATIONAL PICTURE

Figure 3 summarises the increase in PPCI, and the consequent fall in the use of thrombolysis, in England between the second quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2011. The numbers are percentages of all those patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction who underwent reperfusion treatment. Patients who did not receive reperfusion treatment, for whatever reason, are not included. During the third quarter of 2008, around the time of the publication of the NIAP report, 45.8% of those STEMI patients who received reperfusion treatment were being treated by PPCI. The remaining patients (54.2%) were treated with thrombolysis, either in-hospital or pre-hospital. By the second quarter of 2011, a dramatic shift towards PPCI had occurred with 93.8% of patients now being treated with PPCI.

Figure 3. The change from thrombolysis to PPCI in England and Wales 2008-2011. Percentages of all those patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction who underwent reperfusion treatment between the second quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2011. Patients who received no reperfusion treatment are not included.

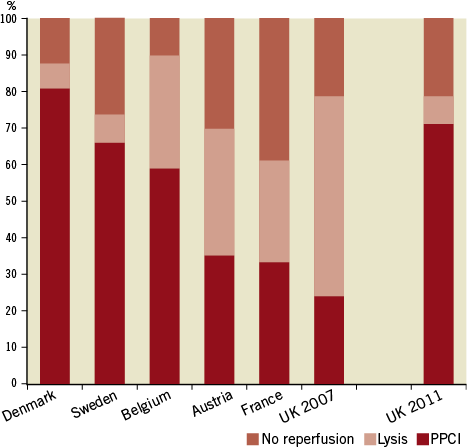

International comparisons are difficult because of differences in the completeness of data collection in different countries. However, an analysis of PPCI rates in Western Europe published in the European Heart Journal showed that the United Kingdom, in 2007-8, was lagging behind many European countries in the development of PPCI services25. Figure 4 shows the PPCI rates for a number of European countries from 2007-8 with the figures for England for both 2007 and 2011, showing the very marked improvement in just three years.

Figure 4. Thrombolysis and PPCI in European Countries 2007/8 vs. UK 2011. Data adapted from reference 25.

PPCI ROLL-OUT BY NETWORK

Figure 3 shows a steady rise in PPCI over the period of three years: this might suggest that the national roll-out of PPCI proceeded at a constant pace throughout England. This was not the case. Some areas, notably the London cardiac networks, were already delivering close to 100% PPCI prior to 2008. Most other areas had a lysis-based strategy with only occasional ad hoc PPCI. The challenges faced by the 28 cardiac networks were very different, and depended on pre-existing infrastructure, pre-existing clinical practice and local geography. As a result, PPCI services were planned and developed at very different rates up and down the country.

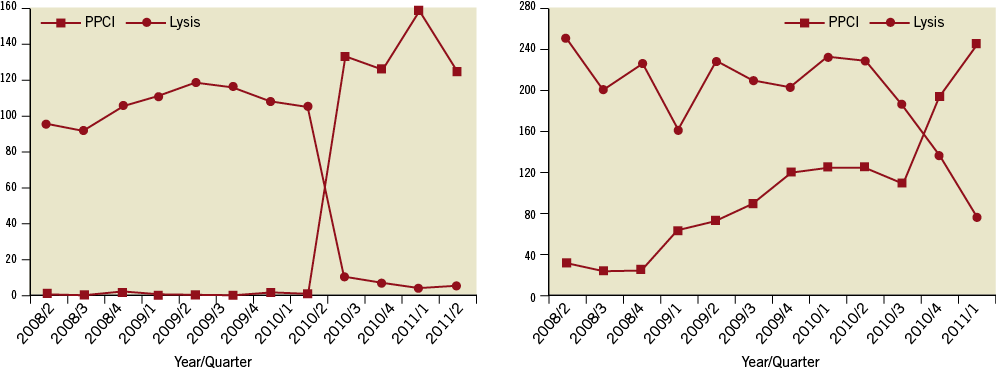

Kent, for example, in south-east England, had no 24/7 PCI centre. Historically, patients from Kent requiring emergency out-of-hours PCI were transferred to a London centre. The development of a 24/7 PPCI service for Kent, therefore, required the co-operation and collaboration of interventional cardiologists from different hospitals to agree which hospital should become the 24/7 PPCI centre. The interventional cardiologists then agreed to contribute to the out-of-hours and weekend rota of the 24/7 centre even though this was not their normal place of work. The Kent 24/7 PPCI service started in April 2010 and resulted in an almost instantaneous switch from lysis to PPCI for the county population (Figure 5). In other cardiac networks, the changeover was more gradual.

East Midlands is one of the largest cardiac networks in the country, covering a population of around three million. The network includes two cardiac surgical centres (Leicester and Nottingham) and a number of large district hospitals (Derby, Lincoln, Northampton and Kettering), many of which were already providing a daytime PCI service. In this network, there was competition to provide PPCI services with a potential for too many provider hospitals. The commissioners of healthcare then undertook a major consultation exercise with all of the potential 24/7 PCI centres and issued a report stating which centres would be commissioned to provide PPCI services. If a centre was not commissioned to perform PPCI, then it would receive no income for any procedures carried out. The activity graph for East Midlands (Figure 5) shows that the rate of change as different centres came on-line at different times was very different to Kent. Nevertheless, by the second quarter of 2011, PPCI had become the dominant reperfusion strategy for STEMI patients in East Midlands.

Figure 5. Number of STEMI patients treated by PPCI and by lysis in Kent (left panel) and East Midlands (right panel) for each quarter from the second quarter of 2008 until the second quarter of 2011

OUTCOMES: ARE WE MAKING A DIFFERENCE?

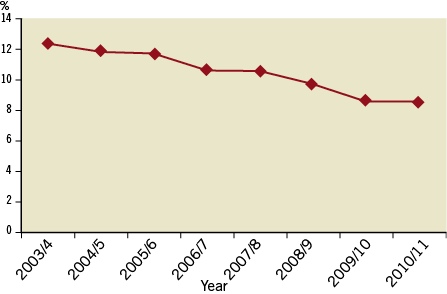

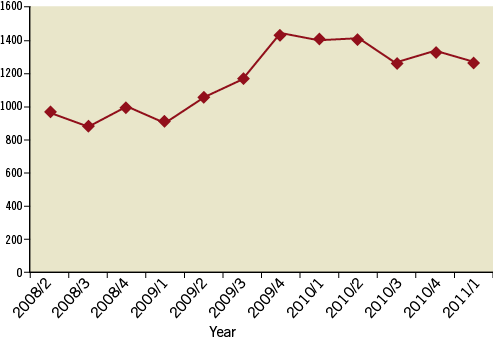

Figure 6 shows the changing 30-day mortality for all patients having ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction over this time period26. Mortality data are obtained from the Medical Research Information Service by the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) and are published in the annual MINAP Public Report. The graph demonstrates that 30-day mortality for STEMI has fallen from around 12.4% in 2003-4 to around 8.6% in 2010-11. It is clear that many different factors will have contributed to the falling mortality, but the switch to PPCI may have been a significant factor from the time of recruitment to the NIAP study in 2005, publication of the NIAP study in 2008 and the NHS Improvement led roll-out programme between 2008 and 2011.

Figure 6. Change in 30-day mortality in England between 2003/4 and 2010/11 amongst patients presenting with STEMI (all-comers)26.

PATIENTS WHO DO NOT RECEIVE REPERFUSION THERAPY

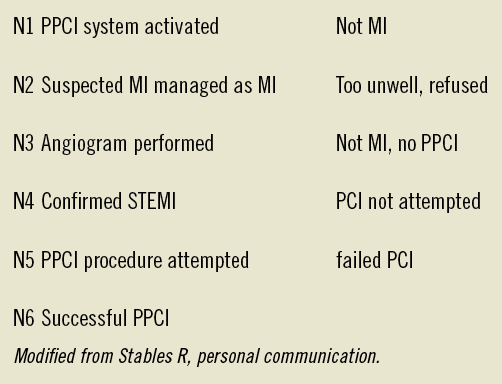

Some patients who are initially thought to be having an ST-segment elevation MI do not receive either PPCI or thrombolysis. Figure 7 shows the proportion of patients in this category and demonstrates a small rise in the numbers from around 25% in 2008 to almost 30% in 2011. It is not clear whether it was clinically appropriate that those patients did not receive reperfusion therapy or whether there were missed opportunities for PPCI or lysis. There are a number of justifiable reasons why patients who have a final (discharge from hospital) diagnosis of ST-elevation MI might not receive reperfusion therapy (e.g., late presentation). Two on-going audits should help in clarifying whether the differences between networks are attributable to differences in clinical practice or to differences in data collection and coding, and whether the decision not to give reperfusion treatment to this group of patients was clinically appropriate or not. These comprise:

– an audit at network level of all “PPCI pathway activations.” This audit is summarised in Figure 8. The audit will capture the reasons why patients may present as a probable STEMI, and hence be referred to as “pathway activations”, but not ultimately receive a successful PPCI procedure;

Figure 7. Change in number of patients receiving no reperfusion therapy 2008-2011 (source MINAP).

Figure 8. Prospective audit of reasons why patients who are referred for possible PPCI do not receive successful PPCI.

– a retrospective audit of patients who have a discharge diagnosis of ST- elevation MI from MINAP but who did not receive PPCI or lysis.

Although the transformation of reperfusion services in the UK has been rapid and effective, analysis of the data at our disposal suggests that there are still significant improvements to be made in some regions, and this will help deliver better outcomes for patients.

Conclusion

Primary PCI is the optimum reperfusion strategy for patients with ST-elevation MI. The National Infarct Angioplasty Project, co-sponsored by the DoH, BCS and BCIS, followed by the PPCI roll-out programme (2008 and 2011) organised by NHS Improvement and the 28 cardiac networks in England, achieved a change in clinical practice that was both swift and consistent across the country. By the second quarter of 2011, 94% of those STEMI patients in England who received reperfusion treatment were being treated by PPCI compared with 46% during the third quarter of 2008. Thrombolysis is still used for a small minority of patients living in remote parts of the country where the estimated transfer time to a PCI programme would be outside that recommended.

This change in practice has been associated with a reduction in mortality and shortened hospital stays. At a time when individual hospitals may be competing for patients with neighbouring hospitals, the role of the cardiac networks has been pivotal in ensuring that the patient pathways developed have been safe and sustainable. Networks can have a major role in the development of other services for patients, particularly specialist services that will not be provided by every acute hospital. These services require close co-operation across networks to ensure the rapid, safe and appropriate transfer of patients between hospitals.

The need to improve reperfusion services has been an international challenge, as exemplified by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Association for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) sponsored “Stent 4 Life” campaign and the Door-To-Balloon Alliance promoted by the American College of Cardiology27-29. The UK experience has paralleled similar processes in other European countries30.

Appendix

Participating centres in the NIAP project.

South Tees PPCI Service: The James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough; University Hospital of North Durham, Durham

West Yorkshire PPCI Service: Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds

Greater Manchester PPCI Service: Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester; Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester

Exeter PPCI Service: Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter

West London PPCI Services: Hammersmith Hospital, London; St Mary’s Hospital, London; Harefield Hospital, London

East London PPCI Service: The London Chest Hospital, Barts and The London NHS Trust

South East London PPCI Service: King’s College Hospital, London