Abstract

This article describes the development of the p-PCI network in Bulgaria. Even though interventional treatment of STEMI in the country was introduced around 1990, it was not performed on a regular basis which made it largely inefficient. The paper tracks the network evolution with all the problems encountered and the solutions undertaken until the present moment. Historically, all the important factors concerning the implementation, such as spreading of PCI centres, networks and infrastructure, training and certification, emergency medical service, public awareness campaigns, 24/7 work, reimbursement, etc., are reviewed. Finally, the current increase of the percentage of STEMI patients treated by p-PCI and the decrease of overall STEMI mortality rates are shown, clearly demonstrating the huge value of the SFL know-how and contribution.

Introduction

Bulgaria is a country located in south-eastern Europe. It has an area of 110,879 km2 and a population of 7,037,935. Bulgaria is a very mountainous country due to its location in the Balkan peninsula. The country has a bad infrastructure, as the roads are in poor condition and there are few highways.

Bulgaria has the highest rates of cardiovascular (CV) mortality in Europe1. The main reasons are the typical Bulgarian cuisine which is abundant in fats, poor medical awareness, and low GDP. All these make the successful treatment of cardiovascular diseases, especially the acute forms, a great challenge.

Reducing cardiovascular mortality is a major priority for the Ministry of Health. Although choosing the most appropriate therapeutic approach is important, far more important is the perfect organisation of the healthcare delivery process in order to reach everyone who needs treatment. Historically, great reforms in the healthcare system began immediately after the transition to democracy and the introduction of free-market capitalism. The first step was the establishment of the National Health Insurance Fund which defined that health care continues to be paid by the government’s health insurance system2 but reorganises the payment process. This was supposed to improve overall organisation and efficiency, since now reimbursement payments are based on services performed (fee per service), rather than budget based, as they were before. Even though interventional treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was introduced around 1990 (during communist rule), it was performed only in a few places and not on a regular basis which made it largely inefficient. Gradually, more 24/7 PCI centres spread around the country. The more p-PCIs were performed, the lower the STEMI mortality. After some serious attempts to enlarge the p-PCI network and more particularly the inclusion of Bulgaria in the SFL Initiative (2009), the overall STEMI mortality dropped significantly to 10.4% (2010). This was also the result of meticulously following the “guidelines” for setting up a national PCI network3.

Further on in the article the main factors relating to the development of p-PCI networks are presented.

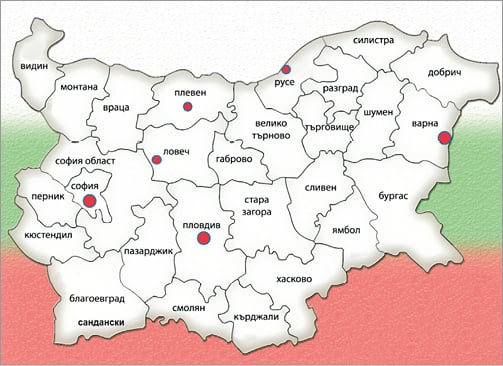

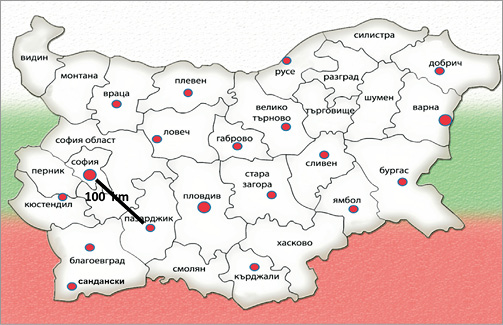

Development of PCI centres map

As mentioned before, p-PCI for STEMI treatment in Bulgaria was introduced around 1990, but а target programme for interventional treatment was implemented only in 2001. Initially, it started in the capital city Sofia and then it spread to the second and the third largest cities in Bulgaria (Plovdiv and Varna). In 2008 there was a concentration of catheterisation laboratories only in a few big cities. This was largely due to the lack of qualified medical staff in the smaller cities of the country. However, after the initiation of training programmes and the subsequent improvement of the skills of healthcare professionals, more PCI centres were established and in the next couple of years most regional cities had at least one. Currently, all those centres provide healthcare services 24/7 which is a requirement of the National Insurance Health Fund in order to be eligible for reimbursements for the PCI procedures performed. Note that the distances in Bulgaria are not too large, so that there is good coverage for STEMI treatment throughout the country as shown by the current PCI cathlab map. Despite these developments, however, there are two regions that are still barely covered by PCI centres (Smolqn and Vidin) where “facilitated” PCIs are performed. The main reasons for this are the mountainous landscape and the lower standard of living in these regions. The result of all these reforms in the organisation of STEMI treatment was an increase in the number of centres from 21 concentrated in several cities (2008) to more than 35 evenly distributed throughout the country, all providing 24/7 service. (Figure 1 and Figure 2)

Figure 1. Map of 24/7 PCI centres in 2008.

Figure 2. Map of 24/7 PCI centres in 2012. For reference on the map a distance of 100 km is shown.

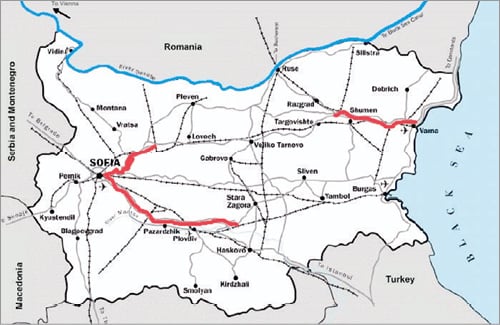

Networks and infrastructure

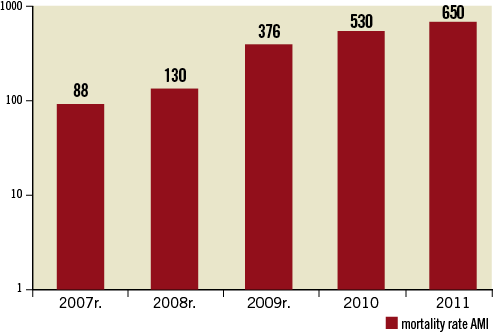

Bulgaria is notorious for its bad infrastructure. The government is taking steps to improve this situation and at the end of 2012 the long awaited completion of the Trakia highway is expected. The improvement of the infrastructure along with the straightforward protocol for transportation of STEMI patients to the nearest 24/7 cathlab has increased the number of patients undergoing p-PCI. This strict regional protocol, approved by the Ministry of Health, stipulates that all STEMI patients should be transported to the nearest cathlab, bypassing the non-PCI centres and thus providing the fastest access to p-PCI for everyone in need. (Figure 3 and Figure 4)

Figure 3. Bulgaria road map, 2008. Shown in red are the completed parts of the two major Bulgarian highways.

Figure 4. Bulgaria road map, 2012. Building of the Trakia highway has made great progress. The inset shows the time of completion for the three remaining lots.

Emergency medical service (EMS)

The EMS in Bulgaria is a structure independent from hospitals. In big cities the EMS teams comprise a physician and a driver, while in small cities and remote villages there are paramedics instead of the physicians. In the past, most of the teams were not well qualified and not well paid. In addition, the ambulances did not have all the necessary equipment. These factors made employment in the EMS undesirable and also instilled a negative opinion regarding the emergency service in the people. Recently, the situation has changed due to increased target EMS funding (the government defined EMS as a priority) and there is a slow but consistent improvement, both in the quality of the provided service and in public opinion. Nowadays, the ambulances are fully equipped and the teams undergo continuous training. The government has also approved a large project for equipping the ambulances throughout the country, and particularly in remote, mountain regions where paramedic teams predominate, with telemedical ECG devices. Some of the first regions to be using such ECG transmitting devices, such as Russe, showed improved recognition of STEMI and shorter time from onset-to-door.

Training

Training and certification of interventional cardiologists rapidly improved after 2009. In 2008 there were only 41 certified interventional cardiologists working in cathlabs. A year later a special course of training, approved by the Ministry of Health, was introduced and since then it has been constantly providing qualified staff for the needs of all PCI centres.

Public awareness campaign

Famous for its unhealthy lifestyle, it was very important for the Bulgarian population to identify and clarify the greatest “heart killers”. The huge value of prevention, the advantages of early diagnosis and treatment, and the severe risk of disability and mortality as a result of neglecting medical advice, should be clearly publicised and understood. The cardiologists’ society in Bulgaria has constantly been stressing (throughout the media) the “proper” lifestyle, condemning all the factors increasing the risk of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. However, so far these activities have been sporadic and there has not been a large-scale, integrated campaign with great media outreach. The Bulgarian SFL steering committee appreciated the importance of such a campaign based on the example of practice in the Netherlands. So finally, at the end of 2011, with the strong support of SFL, a true, integrated, public awareness campaign was created –“Act now, save a life”. It included TV and radio spots, interviews, billboards, press conferences, the launch of the internet site http://spasijivot.com/ (in translation savealife.com), the creation of a Facebook page, and other such activities. This campaign was targeted to virtually every member of Bulgarian society and had the mission to educate people about their cardiovascular status and associated risks. This campaign certainly had a great impact on Bulgarian society; however, the long-term effects are yet to be seen.

PCI registry

A national PCI registry was introduced in November 2011. When fully implemented, it will provide precious “real-life” actual information about the number, the treatment and the evolution of all STEMI patients. The aim of the registry is for it to be used by the government as a quality and quantity control of the treatment.

Politics

The Ministry of Health, urged on by the Cardiological Society and especially the SFL Steering Committee, has also contributed to the good results in recent years. The Ministry approved the new STEMI guidelines, the protocol for AMI patients’ transportation directly by EMS to p-PCI hospitals and from non-PCI centres to hospitals with p-PCI, as well as the pre-hospital fibrinolysis to be performed only in districts without PCI facilities, whereas an angiogram should be carried out for all patients within 24 hours. The Ministry has also supported the training and certification programme, and the necessary condition that cathlabs get reimbursement only if they ensure 24/7 coverage all year round. Trying to improve EMS (increased budget as a priority) and a large-scale telemedicine ECG transmitting project also help to develop better local networks. Frequent Ministry changes and decreasing payment for the AMI treatment, are, however, obstacles to this favourable direction.

Gain

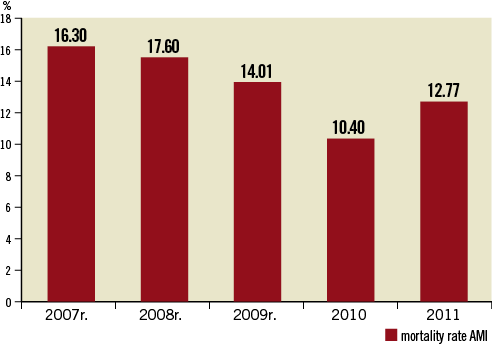

The creation of PCI centres evenly distributed throughout Bulgaria, the training and certification of interventional cardiologists providing 24/7 service in the centres, the improvement in EMS, and the establishment of the transportation protocol to the nearest cathlab, as well as the implementation of an effective local network, have led to the increase in the percentage of STEMI patients treated with PCI (14% in 2008, 25% in 2011). The number of p-PCI/million increased dramatically from 240 in 2008 to more than 600 in 2011. These factors resulted in a decrease in overall STEMI mortality. (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7)

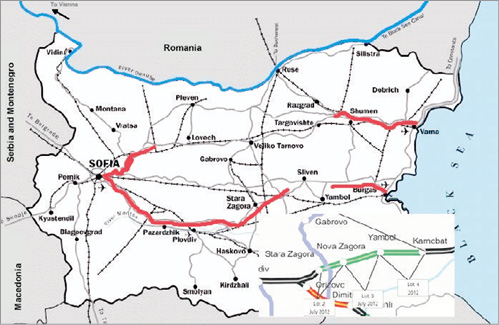

Figure 5. Number of p-PCI/million in Bulgaria for the period 2007-2011.

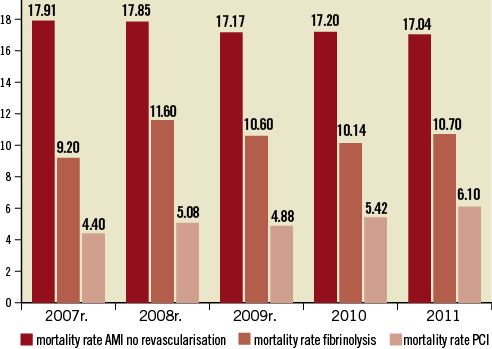

Figure 6. Mortality in AMI patients with no revascularisation, in patients with no fibrinolysis and in patients with PCI, for the period 2007-2011.

Figure 7. Overall STEMI mortality for the period 2007-2011.

The progress of the SFL Initiative led to an increased number of AMI patients undergoing p-PCI with a significant decrease of total AMI mortality from 16.3% to 12.7 % for the period, while p-PCI AMI mortality remains unchanged around 5%.

Issues

Despite the great progress made in p-PCI network development, there are still some issues to be resolved.

The decreasing payment for PCI procedures is quite an unfavourable trend, originating from budget cuts caused by the global financial crisis. This makes working with top shelf materials harder and further decreases staff motivation.

The negative campaign in the Bulgarian media towards interventional cardiology is a dangerous pitfall, as it discourages a lot of patients from undergoing PCI during STEMI.

The patients’ poor awareness of STEMI symptoms still hinders the timely first medical contact and prolongs the onset-to-door times.

Perhaps these are the main reasons for the slight increase of the mortality rate from 10.4% in 2010 to 12.77% in 2011.

Conclusion

Interventional treatment of STEMI in Bulgaria has a long history. In order to reach the patients in need, extremely strict organisation is required. In the last few years, a lot of organisational and legislative steps have been taken to facilitate interaction between patients, GPs, EMS, non-PCI and PCI centres and this has created effective local and national primary angioplasty networks. What really made all these changes effective was the mutual participation and engagement of all the involved parties - the Ministry, the SFL Steering Committee, the Bulgarian societies of Cardiology and Invasive Cardiology, the National Health Insurance Fund, and patient organisations.

All those factors contributed to a decrease in total AMI mortality – the most important indicator of effective efforts. Nevertheless, some issues still need to be resolved to decrease mortality to minimal levels.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.