Abstract

A national programme for PPCI in STEMI patients was started in Romania in August 2010, based on an integrated and well-trained pre-hospital emergency medical system. Ten national centres experienced in PPCI were organised in a 24/7 system in five regional networks, in order to assist STEMI patients from areas offering PPCI within the first two hours after the first medical contact. For centres located further away, a strategy of local thrombolysis followed by transfer to the closest PCI centre was recommended. The total number of PPCI procedures increased from 1,289 in 2010 to 4,209 in 2011. The percentage of PPCI increased from 25.0% in 2010 to 49.32% in 2011. From 40 PPCI/million inhabitants in 2009, we reached 64/million in 2010 and 210/ million in 2011. In the Bucharest area there were 640 PPCI/ million in 2011. The global in-hospital mortality decreased from 13.5% in 2009 to 9.93% in 2011. In 2011 in-hospital mortality was 4.39%, 8.32% and 17.11% for PPCI, thrombolysis and no-reperfusion, respectively. In-hospital mortality was 7.28% in the PCI centres but 14.20% in centres without PCI facilities. The national programme for PPCI had a major impact on STEMI in-hospital mortality in Romania.

Abbreviations

PPCI: primary percutaneous coronary intervention

RO-STEMI: Romanian registry for ST-elevation myocardial infarction

SFL: Stent for Life Initiative

STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Introduction

Romania is the ninth largest country of the European Union (EU) by area (238,400 square kilometres), and its 19 million inhabitants represent the seventh largest population of the EU1. Bucharest, Romania’s capital, is the sixth largest city in the EU, with about two million inhabitants and it has one of the “top 3” population densities (above 5,000 per km2) in the EU, alongside Hauts-de-Seine (France), and Bruxelles-Capitale (Belgium)2.

Before 2009, Romania based its STEMI patient reperfusion strategy on in-hospital thrombolysis. Approximately 40% of patients were treated with thrombolytics. Only a small number of patients (below 5%) were treated by primary angioplasty and more than 50% of patients did not receive any reperfusion procedure at all. As a consequence, in-hospital mortality remained high (around 13.5%) for the period 2000-20093.

The main barriers to a large-scale implementation of the interventional treatment of STEMI patients in Romania included poor reimbursement for PCI procedures, few catheterisation laboratories (only 16 state hospitals with invasive facilities and trained personnel and six other new public hospitals with cathlabs, but not trained in PPCI), a low number of trained interventional cardiologists (only 35 with accreditation), poor personnel motivation due to very low income, poor infrastructure, the existence of large mountainous rural areas, and poor public education regarding STEMI symptoms and the importance of rapid request for help from the emergency medical system.

In October 2009, a joint team of experts from the Romanian Society of Cardiology and the Health Ministry initiated a national programme for the interventional treatment of STEMI patients. Their efforts were based on the data provided by the Romanian registry for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (RO-STEMI). The RO-STEMI data provided a realistic picture of the STEMI challenges throughout the country, including demographic characteristics, time lags between STEMI onset and in-hospital treatment, types of in-hospital treatment, in-hospital outcomes, complications and mortality. Based on these data, the joint team was able to estimate the “STEMI load” for the near future, as well as the costs for a national programme for PPCI in STEMI patients.

In August 2010, a pilot project consisting of five regional STEMI networks was launched. The real-life implementation of this programme of regional networks was possible thanks to the direct involvement of the Health Ministry, which founded a national programme specifically designed for STEMI patients.

In August 2010, Romania also joined the Stent for Life (SFL) European Initiative, promoting widespread use of PPCI as a main treatment strategy for STEMI patients. The Romanian SFL Initiative consists of co-operation between the Health Ministry and the Romanian Society of Cardiology. Representatives from the Health Ministry and the Romanian Society of Cardiology are part of the SFL Romanian steering committee.

Aims

The aim of this report is to present the impact of our national programme on interventional treatment in STEMI patients. In this respect, we present the RO-STEMI data accumulated over the last decade (2002-2011).

Methods

ORGANISING A NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR INTERVENTIONAL TREATMENT IN STEMI

The aim of the national programme was to treat all patients interventionally within the first 12 hours after STEMI onset and within two hours of the first medical contact. This programme was based on the following components:

A DETAILED WRITTEN PROJECT FOR PPCI

A specific project concerning the interventional treatment of STEMI, based on the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines, was written by experts from the Romanian Society of Cardiology. In this project the costs of PPCI were calculated in detail according to the hospitals’ tender prices. This project also defined the criteria for entry of invasive centres to the national programme according to their performance, and emphasised the role of co-operation between the pre-hospital emergency system and the PPCI centres in order to decrease the time from first medical contact to reperfusion. The Romanian Society of Cardiology project was presented to the Health Ministry in October 2009.

BUDGET

An estimation of the number of STEMI patients/year and of the costs of their treatment by PPCI was performed based on the RO-STEMI registry data. The main problem encountered was that the insurance reimbursement was not covering the basic cost of PPCI, which meant that hospitals did not apply this treatment routinely. Even thrombolytic therapy was not performed routinely in some centres, as a result of low reimbursement. The solution implemented by the Health Ministry for the national PPCI programme was to create a special state budget covering the costs of equipment (including stents) used for PPCI. Social Insurance reimbursement would be used only to cover basic hospitalisation costs and the medications given to the patient.

THE NATIONAL PRE-HOSPITAL EMERGENCY MEDICAL SYSTEM

Romania has developed an integrated three-tier pre-hospital emergency system, involving the collaboration of the Health and the Interior Ministries. The pre-hospital emergency response involves:

a. Fire-department-based first responders using ambulances or other vehicles equipped with medical response equipment, including automated external defibrillators (funded by the state budget);

b. The National Ambulance Service, running emergency medical teams with nurses or general practitioners specially trained in pre-hospital emergency care (funded by the State Social Insurance Company);

c. Integrated mobile intensive care units (MICU) functioning as a partnership between the fire departments and the hospital emergency departments. Such teams also use rescue helicopters in partnership with the Ministry of Interior aviation squad (funded by the state budget);

d. The emergency departments, considered part of the hospital care system, but funded separately by the state budget.

Over 900 ambulances manned by firefighters or ambulance nurses are equipped with telemedicine equipment allowing real-time data transmission, involving the monitoring of ECG, pulse-oxymetry, (non-invasive) blood pressure, and 12-lead ECG. All these ambulances and four helicopters are connected to a national coordinating centre. The physicians in charge at the centre direct STEMI patient transfer to the closest emergency hospital trained in reperfusion therapy, in the shortest time possible. The telemedicine system also interconnects the emergency departments of regional and local or county hospitals. This system connects all resuscitation/trauma rooms to the regional hospital by real-time video and audio transmission of ECG and other parameters, allowing specialist physicians to give advice to their colleagues from the field or from the connected hospitals, and help decide concerning patient transfer using helicopters, ground MICU or emergency ambulance.During the first eight months of 2011, in the Bucharest and suburban area alone, fire department and ambulance service emergency response teams performed over 16,000 real-time data transmissions for different categories of patients, including patients with chest pain, leading to the identification of over 300 STEMI patients and allowing them to be directed to PPCI centres.

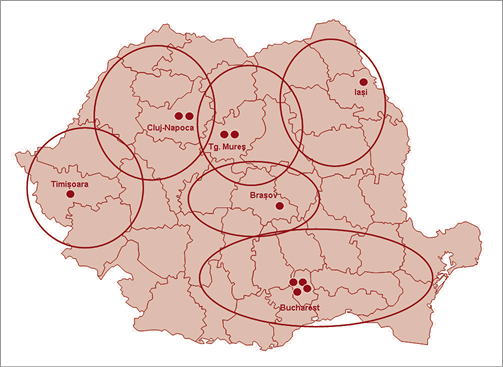

THE STEMI PPCI NATIONAL NETWORK

At the time when our programme was being organised, Romania had ten state centres experienced in PPCI. These centres were organised 24/7 to assist STEMI patients from areas offering PPCI within the first two hours of the first medical contact. All ten centres were also University centres able to train personnel locally. Four of them were organised in Bucharest, to cover the three million people living in the capital and the surrounding counties. These sites functioned by a rota system (two days/week for three centres and once a week for the fourth one). Four state centres were organised in Transylvania (two in Cluj-Napoca and two in Târgu-Mureş, both cities by rota), one in Timişoara and one in Iaşi. Not included in the state national programme, there was also a trained private hospital, located in Braşov, approximately in the middle of the country, also covering an important area (Figure 5). For centres situated too far from PPCI centres, a strategy of local thrombolysis followed by transfer to the closest network PPCI centre was recommended. According to protocol, all STEMI patients received aspirin, a loading dose of 600 mg clopidogrel and an IV bolus of unfractionated heparin (60 IU/kg body weight) or enoxaparin (30 mg IV) before their transfer to the PPCI centre.

THE STEMI PPCI NETWORK PERSONNEL

In the ten participating centres there were 35 cardiologists trained in PPCI, but not all of them had formal certification allowing them to practice PPCI. For these cardiologists the Health Ministry ensured:

– the legal framework for training and taking the certification examination in the subspeciality of interventional cardiology

– the legal framework for instituting 24 hours/day paid on-call schedules.

In each PPCI centre, the administrative department also organised the nursing teams for coverage of the cathlabs for PPCI on a local basis.

MONITORING THE PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION BY THE ROMANIAN REGISTRY FOR ST-ELEVATION MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (RO-STEMI)

The RO-STEMI registry was started in 1997 by the Romanian Society of Cardiology. For the period 1997-1998, this registry was dedicated to thrombolysed patients alone. Between 2000 and 2010, data for all STEMI patients, whether treated by reperfusion strategy or not, were registered on a computerised central database (Microsoft Office Access 1985-2003, Microsoft Corporation). The information was encoded. Data from 469 and 231 patients, respectively, existing in two other small regional registries were also registered on the central database.

A new on-line database was created in 2011 and became available on November 1, 2011. For 2012, the Romanian Society of Cardiology obtained unrestricted financial support for the RO-STEMI registry from the Astra-Zeneca Company. All PPCI centres are required to provide a monthly report of all procedures performed according to the programme and to register their STEMI patient data in the RO-STEMI database. As for the non-PPCI centres, for 2010 and 2011 these reported: a) the annual number of STEMI patients and STEMI mortality for patients treated by thrombolysis or without reperfusion procedures; b) all data from STEMI patients admitted for two months (February and November for 2010, and November and December for 2011). These data were registered on the central database.

STATISTICS

All data were exported to an EXCEL database and analysed using the SPSS 15.0 for Windows programme (LEAD technologies, Inc.). The frequency of a given RO-STEMI variable was evaluated strictly only in patients for whom the existing data had been validated, using the formula X = n / (total patient number - patients ND), where X signifies frequency, n= the number of patients fulfilling the criterion, and ND, “no data” (i.e., when it was not known whether the criterion was fulfilled or not). The results are presented as proportions, mean±SD, and median. For the comparison of mean values, we used the t-test and, for comparison of the proportions, we used the chi square test. Statistical significance was considered to be present for p<0.05.

Results

This report presents data included in the RO-STEMI registry for the last decade (2002-2011).

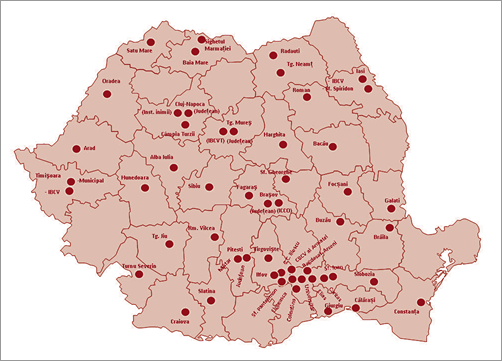

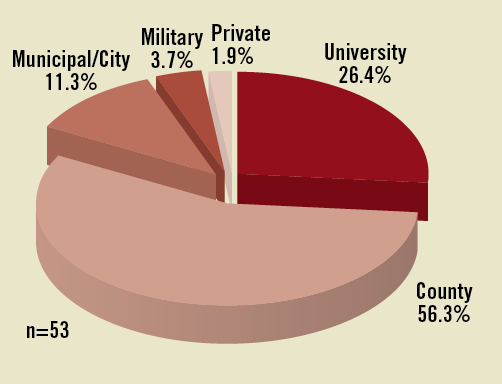

PARTICIPATING CENTRES

The data analysed in the current report originate from 53 sites co-vering the national territory, as shown in Figure 1. Sites included 14 traditional university hospitals (26.4%), 30 county hospitals (56.3%), six municipal or city hospitals (11.3%), two military hospitals (3.7%), and one private hospital (1.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Centres of the Romanian registry for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (RO-STEMI).

Figure 2. The distribution of RO-STEMI centres.

PATIENTS

From January 1st, 1997, to December 31st, 2011, we gathered data regarding in-hospital mortality by procedure (PPCI, thrombolysis or non-reperfusion) for 33,199 STEMI patients. Complete data on demographics, coronary risk factors, infarction location, Killip class on admission, time to admission, time to treatment, in-hospital therapy, STEMI complications and complications of treatment were recorded for 21,948 patients. This report presents data recorded for the last decade (2002-2011). For this period we had data on in-hospital mortality from 30,923 patients and complete data from 21,948 patients (70.97%).

PATIENT AGE AND GENDER

Of the 21,948 patients with complete data, 15,027 (68.47%) were males and 6,921 (31.53%) females. The mean age for females was 68±12 years, eight years higher than for men (60±12 years, p<0.0001).

TRANSPORTATION TO THE HOSPITAL

Eighty-four per cent of RO-STEMI patients arrived at hospitals via the emergency pre-hospital medical system (dedicated ambulances or helicopters). The remaining 16% of patients arrived by private or public transportation.

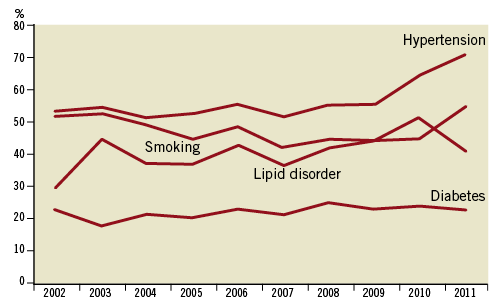

MAIN RISK FACTORS

Hypertension was the most frequent coronary risk factor in RO-STEMI patients, with an incidence of about 55% in 2002-2009. The prevalence increased to 65% in 2010 and to 71% in 2011. Smoking was the second most prevalent risk factor, at 45% for the last decade. Lipid disorders came third, at around 40% in the period 2002-2007. Between 2007 and 2011, however, we noticed a trend towards an increased prevalence of lipid disorders, peaking at 54.70% in 2011. Diabetes prevalence was constant, affecting 22% to 24% of STEMI patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The main coronary risk factors of RO-STEMI patients for the period 2002-2011.

ANTERIOR/NON-ANTERIOR MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

STEMI was anterior (large anterior, anterior, anteroseptal, or high lateral) in 51.63% of patients, and non-anterior (posteroinferior, inferior, true posterior or posterolateral) in 48.37%.

KILLIP CLASS ON ADMISSION

Sixty-eight per cent of the RO-STEMI patients were in Killip class I on admission, 17.65% in Killip class II, 7.93% in Killip class III and 6.06% in Killip class IV.

THE ONSET-TO-ADMISSION TIME

The median of the onset-to-admission time was 210 minutes for the patients admitted between 2002 and 2005, 262 minutes for 2006-2009, and 326 minutes for 2010-2011. A progressive increase of the time-to-admission time correlated with the constant numeric increase of patients sent for PPCI. The median onset-to-admission time for patients treated with thrombolysis, PPCI or without reperfusion increased from 155, 260 and 600 minutes, respectively (2010) to 253, 300 and 617 minutes, respectively (2011).

THE DOOR-TO-BALLOON AND DOOR-TO-NEEDLE TIME

The median door-to-balloon time was 55 minutes and the median of the door-to-needle time was 30 minutes in the RO-STEMI patients for all STEMI patients admitted within the last decade.

THERAPY

PRIMARY ANGIOPLASTY/THROMBOLYSIS/NON-REPERFUSION THERAPY

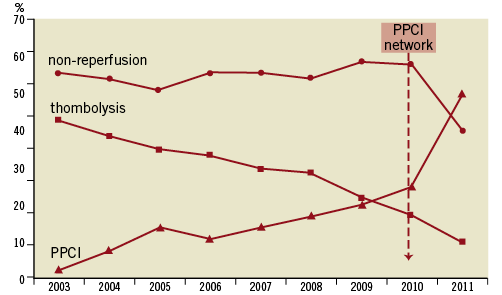

Figure 4 shows STEMI patient distribution by type of therapy: primary angioplasty, thrombolysis, and non-reperfusion therapy. The first PPCI-treated patients were enrolled in the RO-STEMI database in 2003. A slow increase of the percentage of PPCI, from 2% to 20%, was recorded between 2003 and 2009. The percentage of patients treated by thrombolysis decreased from 42% to 22% within the same time frame. However, the percentage of patients receiving neither PPCI nor thrombolysis remained practically unchanged for this period (approximately 55%).

Figure 4. Distribution of primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PPCI), thrombolysis nd non-reperfusion therapy in RO-STEMI patients for the period 2003-2011.

Figure 5. Regional networks for interventional therapy in STEMI patients.

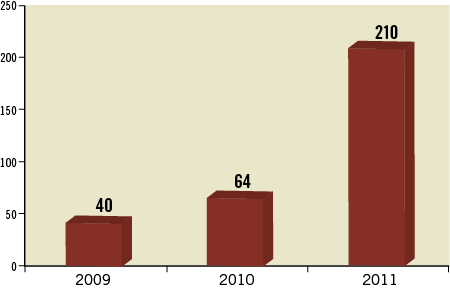

The percentage of PPCI-treated patients increased from 20.0% in 2009 (40/million inhabitants) to 25.0% in 2010 (total 1,289, or 64/million inhabitants) and 49.32% in 2011 (total 4,209, 210/million inhabitants, Figure 6). In the three million inhabitants of the Bucharest area, a total of 1,920 PPCI procedures were performed in 2011 (640 PPCI/million).

Figure 6. Number of primary PCI per million inhabitants in 2009, 2010 and 2011.

The percentage of patients treated by thrombolysis decreased from 17.14% in 2010 to 10.27% in 2011. Globally, 59.59% of our STEMI patients were treated by a reperfusion procedure in 2011 (Figure 4). 2011 was the first year when the percentage of non-reperfused patients decreased significantly compared with the previous years, from around 55% to 40%.

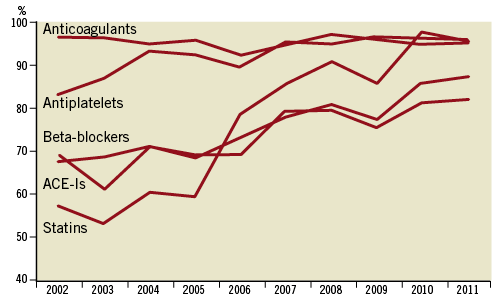

ANTICOAGULANTS

Anticoagulants were used in more than 95% of STEMI patients for the last decade, with a gradual switch from unfractionated heparin (UFH) to enoxaparin (Figure 7). A new trend was noted after 2006: a combination of UFH (administered in the CCU) and enoxaparin (after transfer to the cardiology ward); 28.70% of STEMI patients (in 2010) and 27.21% (in 2011) received this drug combination.

ANTIPLATELETS

The percentage of STEMI patients receiving antiplatelet therapy increased from 83% in 2002 to 95% in 2007 and remained relatively constant until 2011. Aspirin was the only antiplatelet agent administered until 2002. Starting that year, the use of dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) increased rapidly. Thus, 88.79% of STEMI patients (in 2010) and 93.92% (in 2011) received dual antiplatelet therapy (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Dynamics of concomitant medication in RO-STEMI patients for the period 2002-2003.

ANGIOTENSIN CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORS (ACE-IS), BETA-BLOCKERS AND STATINS

An increase in ACE-I and beta-blocker use was seen between 2002 and 2011, from 68% (for both types of drugs) to 87.17% (for beta-blockers) and 81.95% (for ACE inhibitors). The most spectacular increase was seen in the use of statins, from 32.45% in 2002 to 95.0% in 2011 (Figure 7).

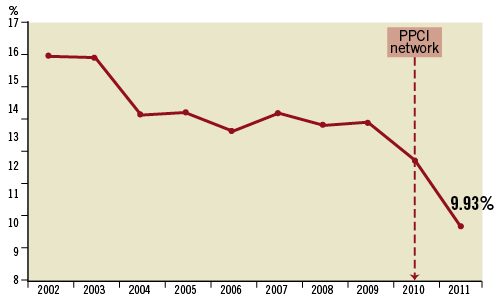

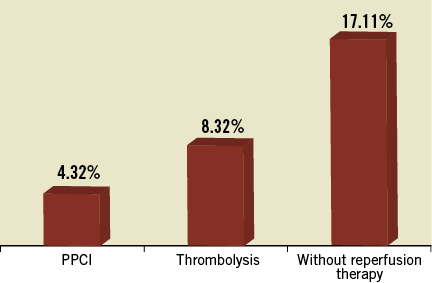

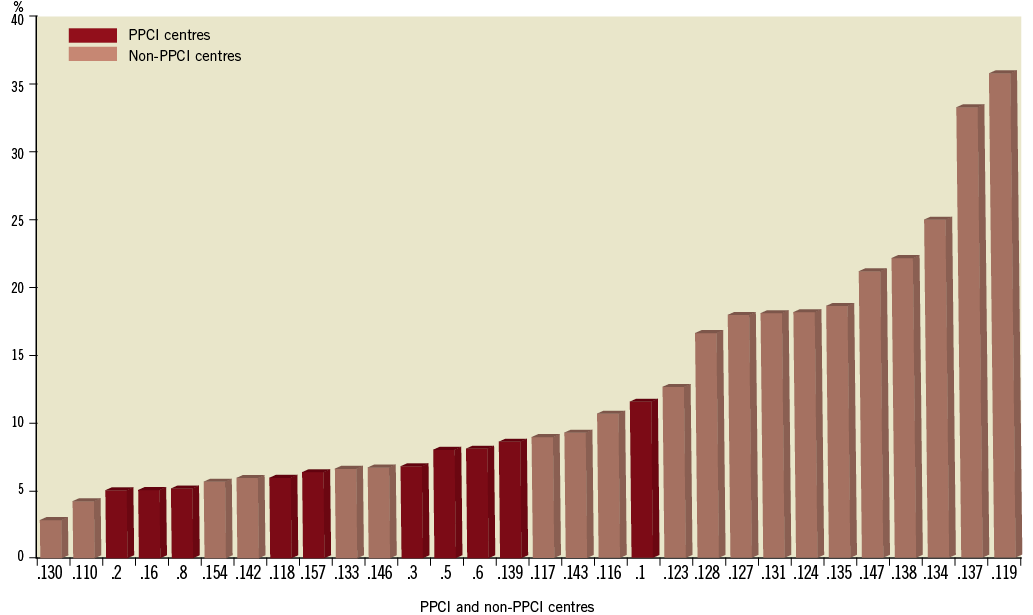

IN-HOSPITAL MORTALITY

Global in-hospital mortality decreased from 15.9% in 2002 to 13.8% in 2004, a trend explained by an increased use of thrombolytics. From 2004 to 2009, the in-hospital STEMI mortality remained unchanged, at around 13.5%. After 2009, the global in-hospital mortality decreased to 12.2% in 2010 and to 9.93% in 2011 (p<0.001 for 2011 as compared to 2009) (Figure 8). For 2011, the in-hospital mortality was 4.39%, 8.32% and 17.11% for STEMI patients treated by PPCI, thrombolysis or without reperfusion therapy, respectively (Figure 9). However, mortality decrease was not homogeneous. Globally, the in-hospital mortality was 7.28% in PPCI centres (including patients non-reperfused due to late admission), but 50% higher (14.20%) in centres without PCI facilities. An in-hospital mortality gradient was seen between PPCI centres and non-PPCI centres with high use of thrombolysis on the one hand, and centres with a high percentage of patients on non-reperfusion therapy on the other (Figure 10).

Figure 8. In-hospital mortality in RO-STEMI patients for the period 2002-2011.

Figure 9. In-hospital mortality in 2011 in RO-STEMI patients treated by PPCI, thrombolysis and without reperfusion therapy.

Figure 10. In-hospital mortality in 31 RO-STEMI centres.

Discussion

This is the first synthesis of the RO-STEMI data performed after the start of our national programme for interventional treatment in STEMI patients (August 1st, 2010). These data show the major impact of this programme in Romania. The current use of telemetry, in an integrated national pre-hospital emergency system, resulted in identification of more than 300 STEMI patients in the field and in sending these patients directly to the PPCI centres. In practice, 50% of STEMI patients were treated by PPCI in 2011, representing a 60% increase as compared to 2009, and a 50% increase as compared to 2010. Thrombolysis was administered in 10.27% of patients treated in 2011, the first year when the percentage of non-reperfused patients decreased (from 55% in 2010 to 40% in 2011). From only 40 PPCI/million inhabitants in 2009 we increased to 64/million in 2010 and 210/million in 2011. In the Bucharest area and surrounding counties there were 640 PPCI/million in 2011, close to the SFL target.

The major impact of the programme consisted of a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality. In 2011, when the programme was fully implemented, the global in-hospital mortality was 9.93%, significantly lower compared with the 13.5% mark which had remained virtually unchanged since 2004.

Interestingly, the number of non-reperfused patients failed to decrease in the second half of 2010, immediately after the programme onset. There are two possible explanations: 1) it took three months for non-PPCI centres to cross the psychological barrier of being required to send STEMI patients to the PPCI centre instead of treating them in the local hospitals; 2) in practice, the first months of the programme only saw substantial changes in centres previously experienced in reperfusion therapy (thrombolysis), who now started a gradual switch to PPCI. Thus, these centres had had very low rates of non-reperfusion therapy use anyway, now only making the transition to a more effective reperfusion strategy (PPCI).

After full programme implementation, an opposite tendency was noted in cardiologists at non-PPCI centres. An ever-increasing preference for transfer to PPCI centres became apparent, and this not only from areas enabling PPCI within the first two hours after the first medical contact. This explains an increase in the median onset-to-admission time from 260 minutes in 2010 to 300 minutes in 2011 in PPCI-treated patients. Pre-transfer thrombolysis in patients initially admitted to non-PCI centres located far from a PPCI centre was administered less frequently than expected.

Conclusions

Within the last decade important changes in STEMI therapy have been seen in Romania (increased use of dual antiplatelet therapy, beta-blockers, ACIs and statins; switching from unfractionated heparin to enoxaparin). Implementation of a national programme for interventional therapy in STEMI patients in August 2010 was followed by a 60% increase of PPCI in 2011 as compared to 2009 (a 50% increase as compared to 2010). Sixty per cent of STEMI patients were treated with reperfusion procedures in 2011 (50% by PPCI and 10% by thrombolysis). The programme had a major impact on in-hospital mortality, which decreased from 13.5% in 2009 to 12.2% in 2010, and to 9.93% in 2011. The impact on mortality was, however, inhomogeneous: the in-hospital mortality decreased in the PPCI centres (7.28%) but remained high (14.20%) in the non-PCI centres.

The near future

Based on the conclusions of this first report, we identified the following ways to improve the national PPCI programme in the near future:

– Commencing a programme of interventional cardiology training for young cardiologists, to start in March 2012

– Switching to new-generation equipment in the ten PPCI centres already involved in our programme (scheduled for 2012-2013)

– Opening of four new invasive centres in the areas still uncovered by this procedure (scheduled for 2012-2014)

– A public campaign of education of the general population in regard to early recognition of acute coronary event symptoms and to awareness of promptly calling the emergency medical system if needed. For this latter goal, we have recently received an important grant on behalf of the SFL Initiative.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Dr Gabriel Adelam for his contribution in the editing of this report.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.