Abstract

Aims: We sought to assess if bivalirudin use during balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) would affect clinical outcomes compared with heparin.

Methods and results: We compared the outcomes of consecutive patients who underwent elective or urgent BAV with intraprocedural use of bivalirudin or heparin at two high-volume centres. All in-hospital events post BAV were adjudicated by an independent, blinded clinical events committee. Of 427 patients, 223 patients (52.2%) received bivalirudin and 204 (47.8%) received heparin. Compared with patients who received heparin, patients who received bivalirudin had significantly less major bleeding (4.9% vs. 13.2%, p=0.003). Net adverse clinical events (NACE, major bleeding or major adverse cardiovascular events [MACE]) were also reduced (11.2% vs. 20.1%, p=0.01). There was no significant difference in the rates of MACE (mortality, myocardial infarction or stroke, 6.7% vs. 11.3%, p=0.1), or vascular complications (major, 2.7% vs. 2.0%; minor, 4.5% vs. 4.9%; p=0.83). After multivariate analysis controlling for vascular preclosure, the use of bivalirudin remained independently associated with reduced major bleeding (OR 0.37; 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.84; p=0.02) while the association was attenuated in propensity-adjusted analysis (OR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.18 to 1.07, p=0.08).

Conclusions: In this registry of patients with severe aortic stenosis, bivalirudin as compared to heparin resulted in improved in-hospital outcomes post BAV in terms of reduced major bleeding, similar MACE and reduced NACE. If verified in a randomised study and extended to the transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) population, these results might indicate a potential benefit for patients undergoing such procedures.

Introduction

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) for severe aortic stenosis results in improvement (albeit transient) of aortic valve haemodynamics and clinical condition, and its role has traditionally been palliative in patients at prohibitively high risk for surgical aortic valve replacement1-4. While BAV alone has not been demonstrated to improve survival5, the emergence of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for high surgical risk or inoperable patients has created interest in the performance of BAV as a bridging therapy6-9. However, the high prevalence of comorbidities in these patients and the large arterial sheaths required for BAV contribute to an increased risk of bleeding and vascular complications8,10,11. Intravenous unfractionated heparin for anticoagulation during BAV has been the standard of care to avoid thrombosis of the intravascular equipment and to attenuate thrombotic microemboli to the brain and elsewhere. The practice of reversing heparin with protamine at the end of the BAV procedure has been variable and has not been studied systematically, in part due to the possible bidirectional clinical effects: heparin reversal might protect from bleeding but might otherwise increase the thrombogenic milieu.

The use of the direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin (Angiomax; The Medicines Company, Parsipanny, NJ, USA) for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has been associated with significant reductions in the rates of both access and non-access-site bleeding compared to heparin with glycoprotein inhibitors12-17. The comparative role of bivalirudin versus heparin in the setting of BAV has not been investigated, but may be theoretically appealing due to the fast reversal of bivalirudin activity and the performance of BAV with substantially larger arterial sheath sizes than those used during PCI.

We therefore compared in-hospital outcomes according to anticoagulation with heparin versus bivalirudin in patients with severe aortic stenosis who underwent elective or urgent retrograde BAV at two high-volume centres in the United States.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all consecutive patients who underwent elective or urgent retrograde BAV with the use of bivalirudin or heparin at the Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA (1/1/2005 to 31/12/2010), and at the University of Miami Medical Center, FL, USA (6/11/2010 to 28/7/2011). In addition to medical record review, all angiograms were examined by an interventional cardiologist blinded to the anticoagulant used. Only the first BAV was included for patients who had more than one BAV during the study timeframe. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both centres.

BAV TECHNIQUE

A stable operator team (i.e., same operators for all BAV) performed the BAV procedures in both centres; both teams consisted of experienced operators with established interventional practice and significant BAV experience in the respective centres before this study.

At Mount Sinai, BAV was performed via femoral arterial access unless precluded by severe peripheral vascular disease, in which case brachial arterial access was used (n=1). Until June 2008, patients routinely had two arterial access sites to allow simultaneous measurement of the transaortic gradient. Subsequently, single arterial access and transaortic measurement via a dual lumen pigtail catheter became standard clinical protocol. Femoral angiography was performed routinely prior to placing the large arterial sheath. Following angiography, the use of the “preclosure” technique with one or two Perclose ProGlide (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) devices, deployed before insertion of the large sheath18, was at the operator’s discretion. Placement of a transvenous right ventricular (RV) pacemaker for rapid ventricular pacing at the moment of balloon inflation was also at the operator’s discretion, with the pacing wire inserted through the same venous sheath after baseline right heart catheterisation.

Either bivalirudin or heparin was used per operator preference after 2007. The standard dose of bivalirudin included a 0.75 mg/kg IV bolus followed by 1.75 mg/kg/hr infusion in patients undergoing BAV and PCI, a bolus only for BAV alone, and reduced doses (0.375 mg/kg bolus) in BAV patients deemed at high bleeding risk as judged by the operator. The unfractionated heparin bolus was 40-50 IU/kg IV. Protamine was not routinely used among patients receiving heparin, being reserved for those patients for whom there was a specific concern regarding developing bleeding at the end of the BAV procedure.

In general, the University of Miami clinical centre followed the same aforementioned approach to BAV. Patients received anticoagulation with either bivalirudin or heparin at the operator’s discretion before BAV. All patients who received bivalirudin had both a bolus (0.75 mg/kg) and an infusion (1.75 mg/kg/hr) which was discontinued at the removal of the final BAV balloon. All BAV procedures were performed using rapid right ventricular pacing at a rate of 180-200 bpm and non-compliant balloons. Of note, in all combined procedures BAV was performed before PCI.

At both centres, access-site haemostasis was achieved with manual compression when the ACT level was <180 seconds if the preclosure technique was not used, as per operator preference. Blood transfusions post procedure were ordered at the physician’s discretion. In general, patients were transfused for active or overt bleeding associated with haemodynamic instability or, in the absence of symptoms, if the haemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL. All patients enrolled from Mount Sinai in the current analysis underwent BAV for palliation of symptoms alone, whereas 16 patients from Miami had BAV as a bridge to TAVI. None of these patients underwent TAVI in the same admission as BAV (mean time from BAV to TAVI, 108 days).

STUDY ENDPOINTS AND DEFINITIONS

The primary endpoint was major bleeding, defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type ≥319. BARC type 3 bleeding includes bleeds that are evident clinically, or by laboratory or imaging results, which require blood transfusion, surgical intervention or intravenous vasoactive drugs; overt bleeds with a haemoglobin drop ≥3 g/dL; bleeding that causes cardiac tamponade; and intracranial or intraocular bleeds that compromise vision. BARC type 4 (CABG-related) bleeding was not applicable to this study. BARC type 5 bleeding describes bleeds that directly result in death with no other cause. Bleeding events were also defined using the TIMI, GUSTO and VARC definitions20-22.

Vascular complications, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), acute kidney injury and the individual components of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE, composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke) were defined according to Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) criteria22. Net adverse clinical events (NACE) included MACE or major bleeding (BARC type ≥3). All in-hospital events were adjudicated (using source documents) by an independent clinical events committee blinded to the antithrombotic agent administered.

Patients were considered frail if they had moderate or severe dementia, were bedbound, a nursing home resident or dependent for all activities of daily living. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from the serum creatinine using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula23. One-year mortality was ascertained from the social security death index.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for cell sizes <5. Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median (interquartile range) and were compared using the Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, respectively. The independent association between bivalirudin use and major bleeding was determined using stepwise multivariable logistic regression with entry/exit criteria of 0.2 and 0.1, respectively. Candidate variables were bivalirudin (vs. heparin), age, gender, warfarin, frailty, anaemia, use of preclosure, peripheral arterial disease, eGFR, concomitant bleeding, year of procedure, prior BAV, the number of arterial access sites used and the logistic EuroSCORE. In addition, we assigned propensity scores to all patients using a logistic regression model with bivalirudin vs. heparin use as the dependent outcome. Separate propensity score-adjusted analyses were then performed to account further for the baseline differences between bivalirudin and heparin groups24,25. Pre-specified subgroup analyses were performed in the following groups: age and EuroSCORE above and below the median; sex; eGFR above and below 60; presence or absence of diabetes, anaemia, peripheral arterial disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter, frailty, or prior CABG and access-site “preclosure” vs. manual compression. Formal testing for multiplicative interaction was performed between each subgroup and the main effect of bivalirudin vs. heparin use on the outcome of major bleeding.

A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered significant for all statistical comparison. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 11.2 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

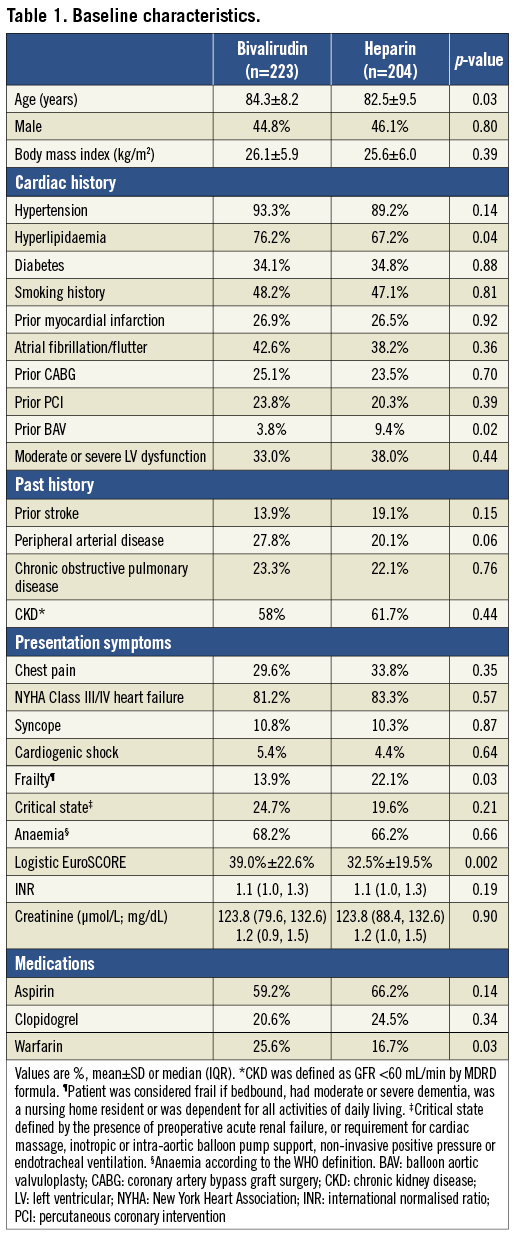

Among 427 BAV patients studied, 223 patients (52.2%) were anticoagulated with bivalirudin and 204 patients (47.8%) with heparin during the procedure. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics. Compared to the heparin group, patients in the bivalirudin group were older, and were more likely to have hyperlipidaemia and to be on warfarin.

A higher proportion of patients who received bivalirudin were in a critical state pre-BAV, with acute renal failure or requiring cardiac or respiratory support. The logistic EuroSCORE was higher in the bivalirudin group whereas patients treated with heparin were more likely to be frail.

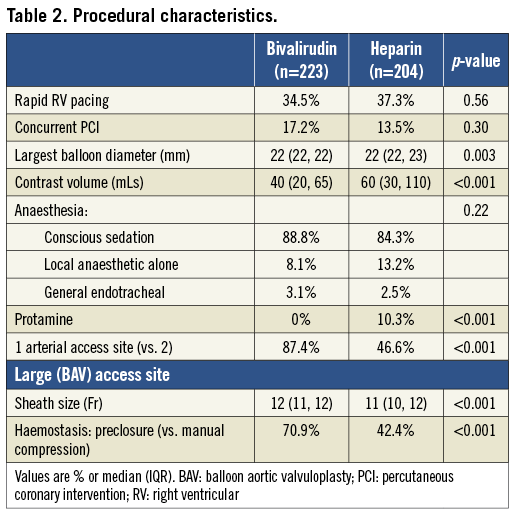

Patients who received heparin received greater contrast volume and had more frequent use of bilateral femoral arterial access (Table 2). Patients who received bivalirudin had larger diameter arterial sheaths and higher use of the arterial preclosure technique for haemostasis of the large bore access site using a vascular closure device. The types of anaesthesia used were similar between the groups.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

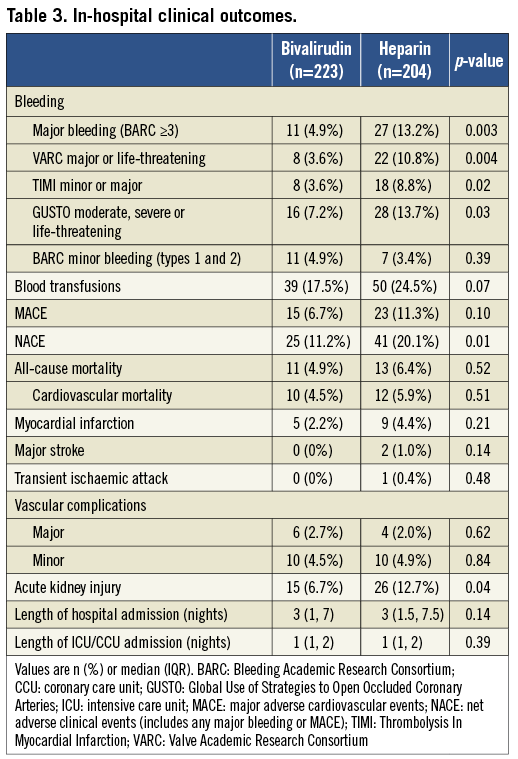

Patients who received bivalirudin compared with heparin had significantly reduced in-hospital major bleeding (Table 3). Among all major bleeds in this study (BARC ≥3, n=38), the majority (n=24, 63.2%) were attributable to the access site while 14 (36.8%) occurred elsewhere. Compared to heparin, bivalirudin was associated with a reduction in both access (3.6% vs. 7.8%, p=0.06) and non-access-site bleeding (1.3% vs. 5.4%, p=0.02), respectively. Non-access-site bleeds included pericardial (n=5), gastrointestinal (n=3), genitourinary (n=1) and five of unknown or unclear source. There was a trend towards more frequent blood transfusions with heparin versus bivalirudin. There was no significant difference in minor bleeding (BARC types 1 and 2) between the groups. Only four of the major bleeds occurred at the secondary access site (i.e., the small femoral arterial sheath), one in a patient who received bivalirudin and three in patients who received heparin; none of these patients had device closure attempted at this site. Inclusion of these events did not impact on the overall result.

Patients who received bivalirudin compared with heparin had significantly lower in-hospital NACE with no significant difference in the rates of MACE, transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or vascular complications. There was increased acute kidney injury in patients in the heparin group. One-year mortality was similar in the two groups.

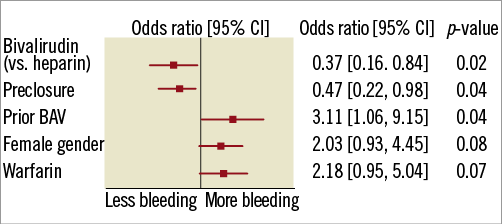

After multivariate analysis, the use of bivalirudin remained significantly associated with reduced major bleeding (Figure 1). Results from the propensity score-adjusted analysis were consistent with the overall findings of lower bleeding risk with bivalirudin vs. heparin use (OR 0.44; 95% CI: 0.18 to 1.07).

Figure 1. Independent predictors of major bleeding. BAV: balloon aortic valvuloplasty; CI: confidence interval

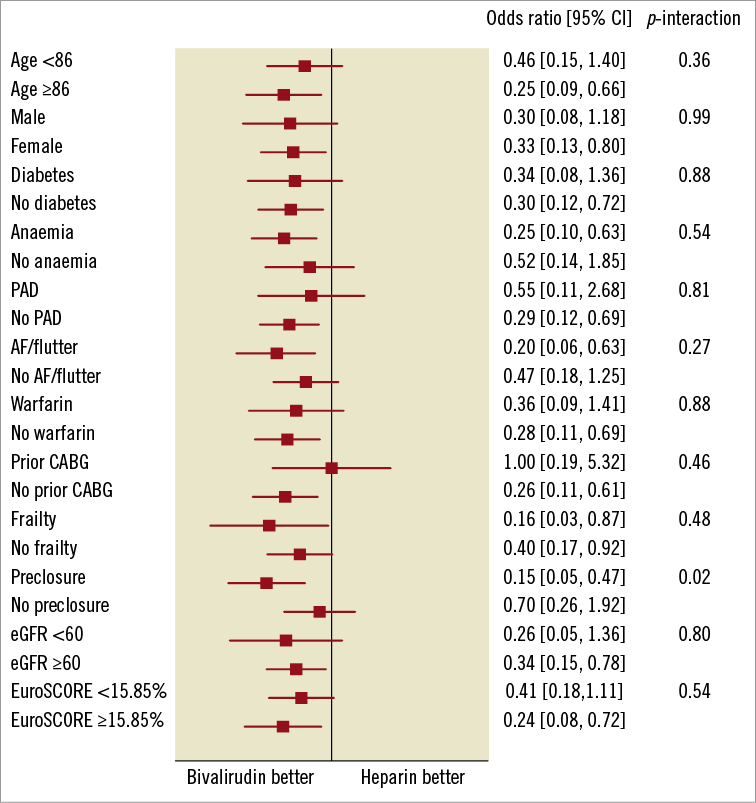

The effect of bivalirudin compared with heparin on major bleeding was similar for all the pre-specified subgroups with the exception of arterial access preclosure; bivalirudin yielded particularly better results in patients selected for closure (p interaction 0.02; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Subgroup analyses of major bleeding. AF: atrial fibrillation; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; PAD: peripheral arterial disease

At one-year follow-up, the all-cause mortality rate was similar between the two groups (bivalirudin group 32.7% vs. 34.5% in heparin group, p=0.65).

Discussion

In the present registry, we found that the use of bivalirudin compared with heparin during BAV was associated with a large reduction in major bleeding events during hospitalisation. The reduction in bleeding was evident not only by the BARC definition, but also by TIMI, GUSTO and VARC bleeding definitions. While the magnitude of effect was similar, results were attenuated following propensity adjustment. Rates of in-hospital MACE, individual components of MACE (death, MI, stroke), TIA and vascular complications were not significantly different between the two groups. Consequently, the net adverse event rate (a combination of bleeding and MACE events) was lower with bivalirudin.

Additionally, there was a positive interaction between the use of bivalirudin and preclosure, with most benefit in reducing bleeding complications in this frail elderly cohort undergoing BAV with large bore sheaths seen with the combination of both bivalirudin and preclosure. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the outcomes of BAV using bivalirudin.

Our findings parallel the results of PCI trials, in which the use of bivalirudin compared with heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) resulted in a relative reduction in 30-day rates of major bleeding by approximately 40%, with no significant difference in composite ischaemic study endpoints12-14. Use of GPI is not indicated in BAV and anticoagulation is usually achieved with heparin alone. Despite this, we found a marked difference in bleeding events, which may reflect the high bleeding risk inherent in the older BAV population, as well as in the procedure itself.

One concern regarding the use of bivalirudin has been the lack of an antidote if required for acute bleeding. However, two registry studies failed to show that patients who had coronary perforations during PCI had worse outcomes with bivalirudin compared with heparin26,27. Pooled results from three randomised trials also showed no significant difference in results post coronary perforations in patients receiving bivalirudin vs. heparin plus GPI28. Similarly, in our study, bivalirudin was not associated with an increase in the severity of bleeding events. This may be attributable to bivalirudin’s short half-life and the gradual elimination of its activity, as well as to delayed or imprecise reversal of heparin with protamine.

We found that the rates of in-hospital bleeding among patients receiving heparin were lower than the 24-hour bleeding rates reported in older BAV registries10,11. This was in spite of the use of a more inclusive definition of major bleeding, the older age of patients, and higher prevalence of diabetes and peripheral arterial disease in the current registry. A better understanding of bleeding risks, better vascular access technique, use of weight-adjusted anticoagulant dosing and vascular preclosure, may account for this reduction in bleeding rates. In addition, the risk profile of our study population, similar to a more contemporary BAV registry8, likely reflects a broader temporal change in clinical practice. With the improved safety of BAV, and more recently the new indication for BAV as a bridge to TAVI, patients at increasingly higher risk are being considered for treatment with BAV9.

Despite the difference in bleeding rates in the two groups, there was no significant difference in mortality whether bivalirudin or heparin was used during BAV. This may be explained by the poor prognosis of severe aortic stenosis. Previous studies in BAV have not demonstrated any survival benefit with BAV compared with the natural history of severe aortic stenosis1,5,21,29. The high rate of one-year mortality observed in our study is consistent with rates reported in previous registries1,3,5,8. It may be that strategies to reduce complications of BAV, such as the use of bivalirudin instead of heparin, may, at best, only reduce procedural morbidity and improve quality of life. In contrast, blood transfusion post TAVI has been associated with increased 30-day and one-year mortality30. Whether or not there is any associated mortality benefit with bivalirudin use in patients undergoing BAV as a bridge or with concomitant TAVI merits further investigation.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study and, while we attempted to adjudicate all events from source files, our findings are exploratory and should be considered hypothesis-generating. We only collected demographic data that were available in the hospital chart. As there was inadequate information to quantify patient frailty according to published frailty scoring systems, we used surrogate variables of severe impairment in mobility, activity and cognition to classify a patient as frail. There may be selection bias in the choice of antithrombotic agent, with operators using bivalirudin in patients deemed at higher risk for bleeding. Notably, selection of anticoagulation regimen was done pre-procedurally, whereas selection for preclosure was actually performed after completion of the appropriate femoral angiogram. In this way, severe peripheral arterial disease, a risk factor for vascular complications and access-site-related bleeding, may have precluded the use of preclosure of the large-bore, arterial access site in these patients. While peripheral arterial disease was included in the multivariable model, the severity of disease was not captured and may have been a confounder. Furthermore, the variable time course of anticoagulant assignment and BAV procedures in the two clinical sites may have introduced additional unmeasured confounders. Finally, the number of patients who had BAV as bridge to TAVI (n=16, and no TAVI in the same admission as BAV) was too small to perform any meaningful comparisons regarding one-year mortality in these patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, within this retrospective review of high-risk patients undergoing elective or urgent BAV, the use of bivalirudin compared with heparin as the procedure anticoagulant resulted in less major bleeding with no significant difference in mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke or vascular complications between groups. Accordingly, the net adverse event rate was also improved. Prospective studies are required to confirm these findings and to understand the applicability of these findings to other percutaneous procedures requiring large-bore arterial access. If verified in randomised studies and extended to the TAVI population, these results might indicate a potential benefit for patients undergoing such procedures.

Funding

This investigator-initiated study was supported by The Medicines Company.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Kini has received speaker’s honoraria from Medscape. M. Cohen has received research funding and consulting honoraria from The Medicines Company and is a consultant for Medtronic. R. Mehran has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson and Regado, and has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi and The Medicines Company. J. Kovacic is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1K08HL111330-01 and has no conflicts of interest to declare. B. O’Neill has financial interest in Accumed, and has received research support from the Medicines Company. S. Sharma has received speaker’s honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo Inc., Eli Lilly, Medscape and The Medicines Company. G. Dangas has received a research grant from The Medicines Company. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.