Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) represents one of the most common valvular heart diseases affecting almost 10% of the population >75 years of age1. According to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, surgical interventions still represent the gold standard for treatment of severe MR2. However, many patients do not undergo surgery due to increased surgical risk, which has driven the field of percutaneous mitral valve (MV) treatments, including repair and replacement technologies3. As catheter-based MV repair options are increasingly adopted in clinical practice, they require accurate preprocedural imaging, providing detailed anatomic information about the MV and adjacent structures such as the circumflex artery (Cx) to avoid periprocedural injury1.

This study comprehensively assessed the dynamic anatomic relationship between the mitral annulus (MA) and Cx in normal subjects and in patients with severe MR.

Methods

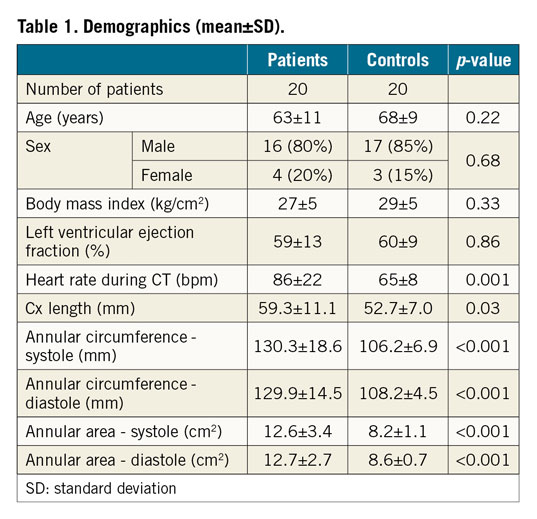

Twenty patients with severe primary MR, determined by transthoracic echocardiography, termed “patients”, and 20 patients without cardiac disease, termed “controls”, undergoing computed tomography (CT) were included (Table 1). All subjects had right dominant coronary supply.

CT DATA ANALYSIS

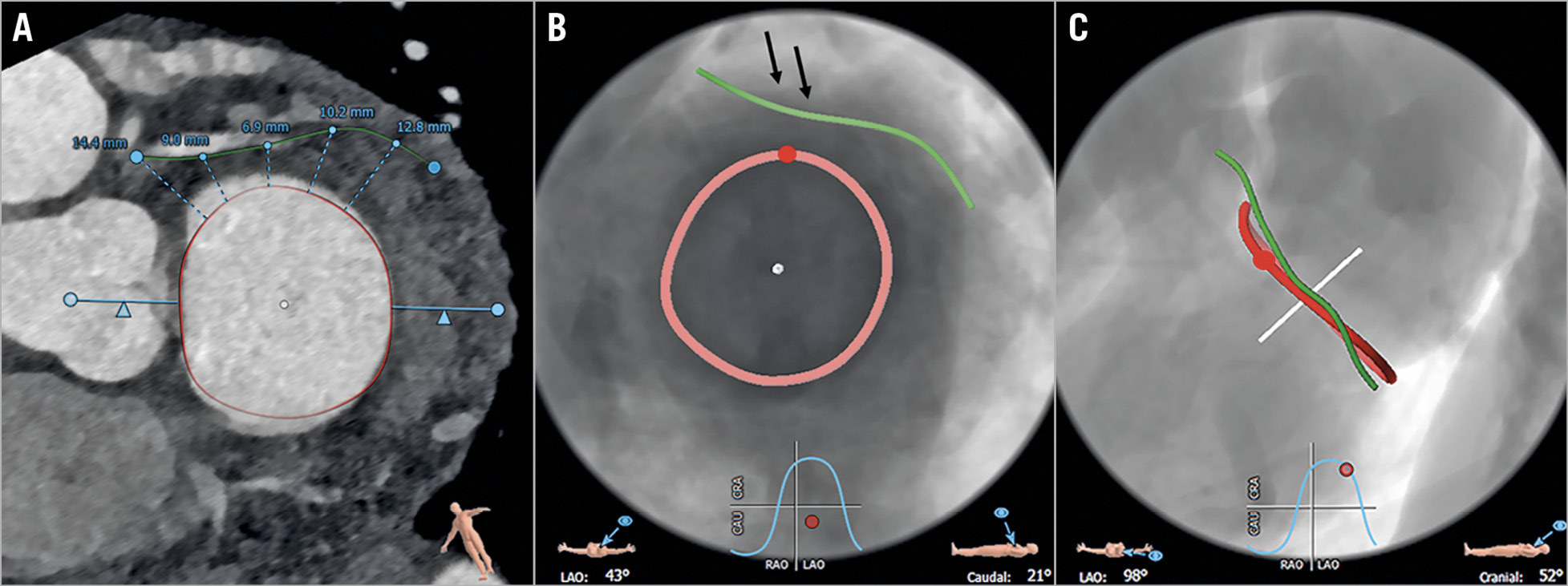

Image analysis was performed using a prototype advanced visualisation, segmentation and image analysis software (3mensio Structural Heart 6.0 beta; Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, the Netherlands). MA and Cx dimensions, and distances between the MA and Cx were measured in all phases by two independent readers (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Image analysis. CT (A) and fluoroscopic views of the MA and Cx in a patient with severe MR (B: 43° LAO; C: 98° LAO) in mid-diastole (80%), including distance measurements of five seed points in this representative patient (average number of seed points, n=6) (A). Black arrows: short segment of the proximal Cx with consistently narrowest distances (B), opposite the ALC (indicated by red point).

Details regarding CT protocol and statistical analysis can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1 and Supplementary Appendix 2.

Results

DIMENSIONS AND GEOMETRY OF THE MA AND CX

MA areas and circumferences were significantly larger, and the Cx was significantly longer in patients than in controls in all phases (p<0.001) (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). The MA showed no increased flattening (difference between three-dimensional [3D] and two-dimensional [2D]) in patients compared to controls, but 3D geometry of the MA was maintained in both groups (difference between 3D and 2D: 2.8 mm in patients; 2.6 mm in controls).

DISTANCES AND SPATIAL RELATIONSHIP OF THE MA TO THE CX

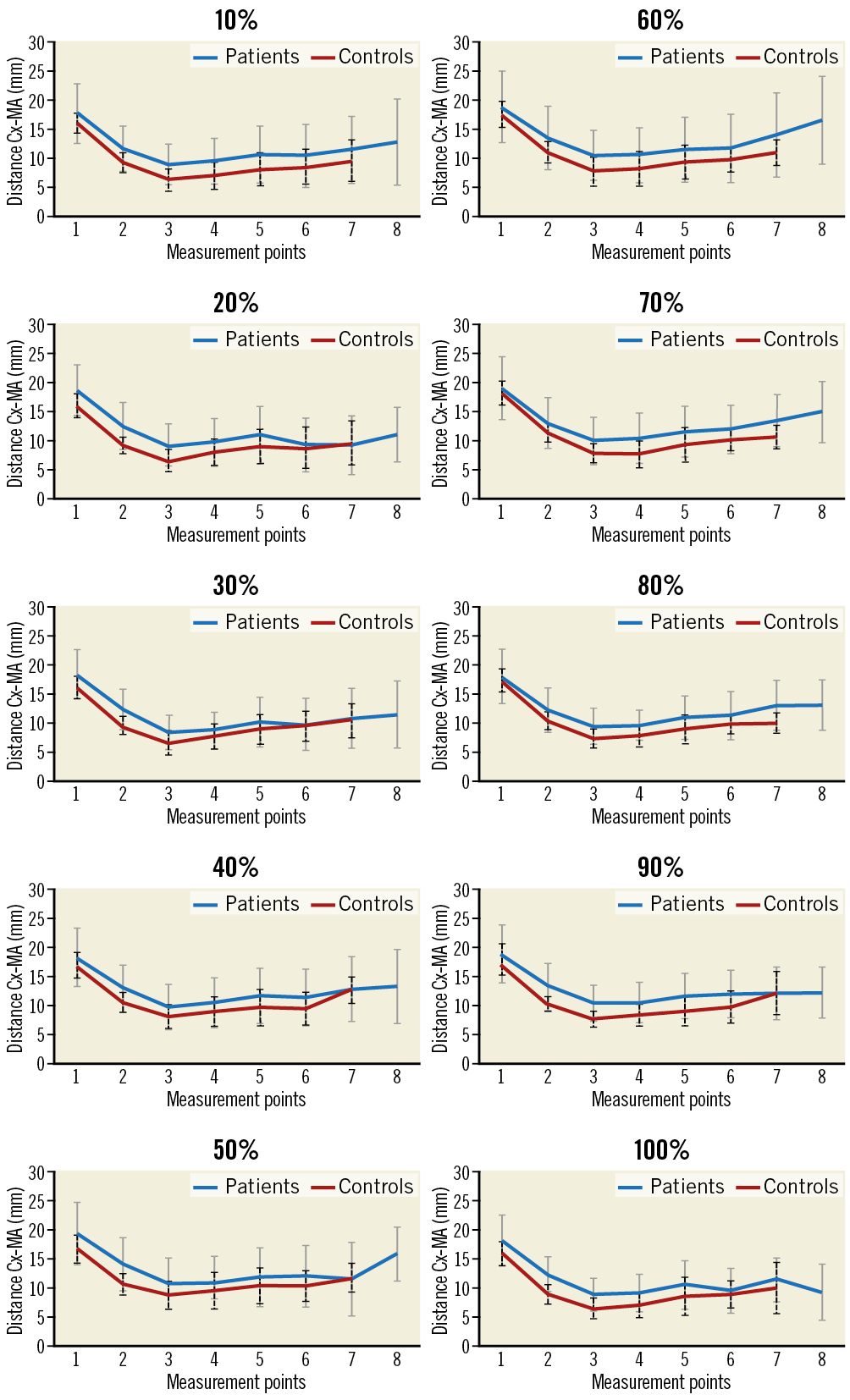

Distances between the MA and Cx were significantly larger in patients compared to controls for all measurement points and all phases (p=0.001-0.008) (Figure 2). In both cohorts, distances between the MA and Cx continuously decreased until point 3 and increased to the last point.

Figure 2. Distances (and SD) between the Cx and MA for all measurements and phases in patients with severe MR (blue line; SD: grey line) and controls (red line; SD: black dashed line).

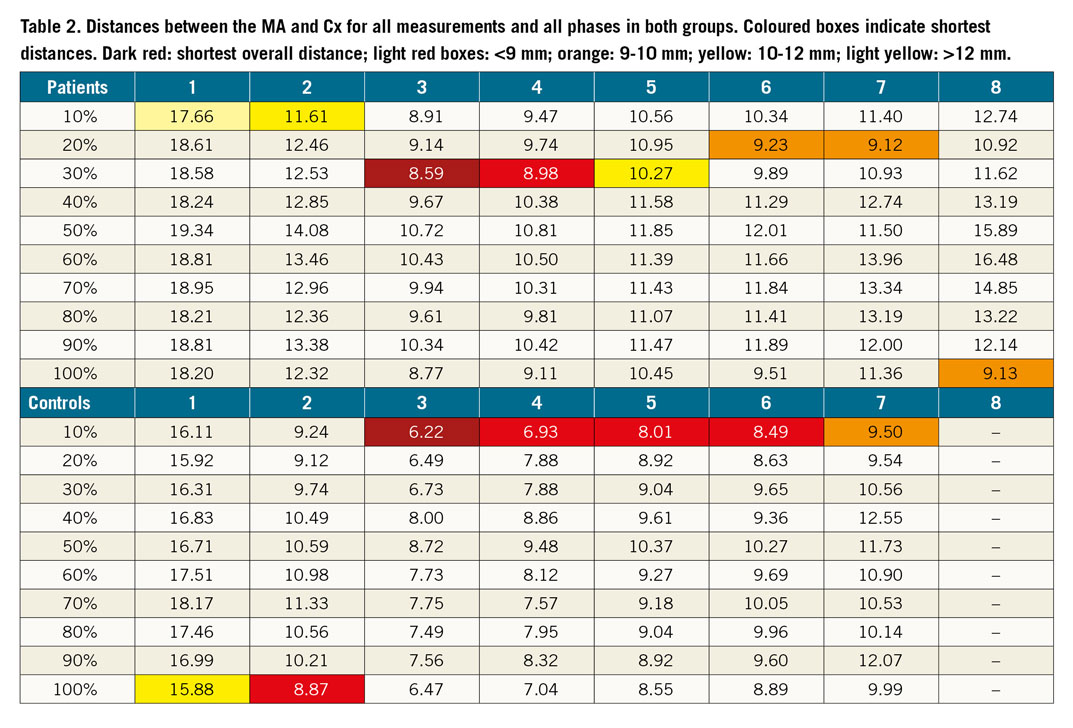

The shortest distances between the MA and Cx were found in patients in the proximal segment in mid-systole (30%) and in controls in the proximal segment in early systole (10%) (Table 2).

In both cohorts and in all phases the anterolateral commissure (ALC) was opposite to measurement points 3 and 4 (proximal Cx) (Figure 1).

Displacement of the Cx in relation to the MA throughout phases compared between mid-systole (30%) and mid-diastole (70%) was similar in the proximal Cx (measurement point 3) for both groups, whereas larger displacements were found in patients in distal Cx segments in systole (Supplementary Figure 1).

Discussion

We consistently found larger areas and circumferences of the MA and a longer Cx in patients than in controls. There was a consistent relationship between the Cx and MA throughout the cardiac cycle, showing overall larger distances in patients compared to controls, with decreasing distances between the Cx and the MA to the level of the ALC, while distances progressively increased more distally.

Our study revealed 3D distances between the Cx and MA of between 6.2±1.9 and 6.9±2.4 mm in controls and 8.6±2.9 and 9.0±3.0 mm in patients, including overall shortest distances in the proximal segment in both groups (controls: 6.2±1.9 mm; patients: 8.6±2.9 mm).

Our analyses confirm previous results3 comparing distances between the MA and Cx in controls and in patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and/or MR, measuring larger distances in patients compared to controls (7.6±2.3 mm vs 5.8±1.8 mm), with shortest distances in the proximal to mid Cx (average 6.4±2.1 mm). The ALC corresponds to the origin of the P1 segment of the posterior leaflet. Thus, caution must be exercised to avoid Cx injuries, as this region is the landmark for anchor positioning of most direct annuloplasty devices.

Cardiac motion is larger at the base of the heart at the location of the atrioventricular groove than anteriorly in the course of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. Similar to the right coronary artery (RCA), the Cx shows large displacement with highest movements in systole4,5. Consistent with that, we found a higher displacement of the Cx in systole, being more pronounced for mid and distal Cx segments, with reduction of displacement at end-systole in the proximal Cx.

Limitations

The retrospective study design, small number of patients (none with left coronary dominance) and the fact that the study was not designed for a specific device are all limitations.

Conclusion

Our study includes a detailed analysis of the 3D dynamics between the MA and Cx throughout the cardiac cycle in controls and patients with severe MR. In patients, the shortest distances between the MA and Cx were found in mid-systole in the proximal Cx, opposite the ALC, which is an important landmark for annuloplasty devices.

|

Impact on daily practice Transcatheter therapies for MR require pre-interventional imaging to obtain detailed and comprehensive knowledge of the MV geometry and its relationship to adjacent structures such as the Cx to avoid potentially fatal injury. |

Conflict of interest statement

M. Taramasso is a consultant for St. Jude Medical, and also reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, 4Tech, Edwards Lifesciences and CoreMedic, outside the submitted work. F. Maisano is a co-founder of 4Tech, a consultant for Abbott Vascular, St. Jude Medical, Medtronic and Valtech Cardio, receives royalties from Edwards Lifesciences, and also reports personal fees from Abbott, Edwards Lifesciences, Mitraltech, and other from Edwards Lifesciences, Mitraltech and 4Tech, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.