Abstract

Background: Critical culprit lesion locations (CCLL) such as left main (LM) and proximal left anterior descending (LAD) are associated with worse clinical outcome in myocardial infarction without cardiogenic shock (CS).

Aims: We aimed to assess whether CCLL identify a subgroup of patients with poorer prognosis when presenting with CS.

Methods: In the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial, a core laboratory reviewed all coronary angiograms to identify CCLL. A CCLL was defined as a culprit lesion with a >70% diameter stenosis of the LM, LM equivalent (>70% diameter stenosis of both proximal LAD and proximal circumflex), proximal LAD or last remaining vessel. We evaluated the primary study endpoint of the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial according to CCLL.

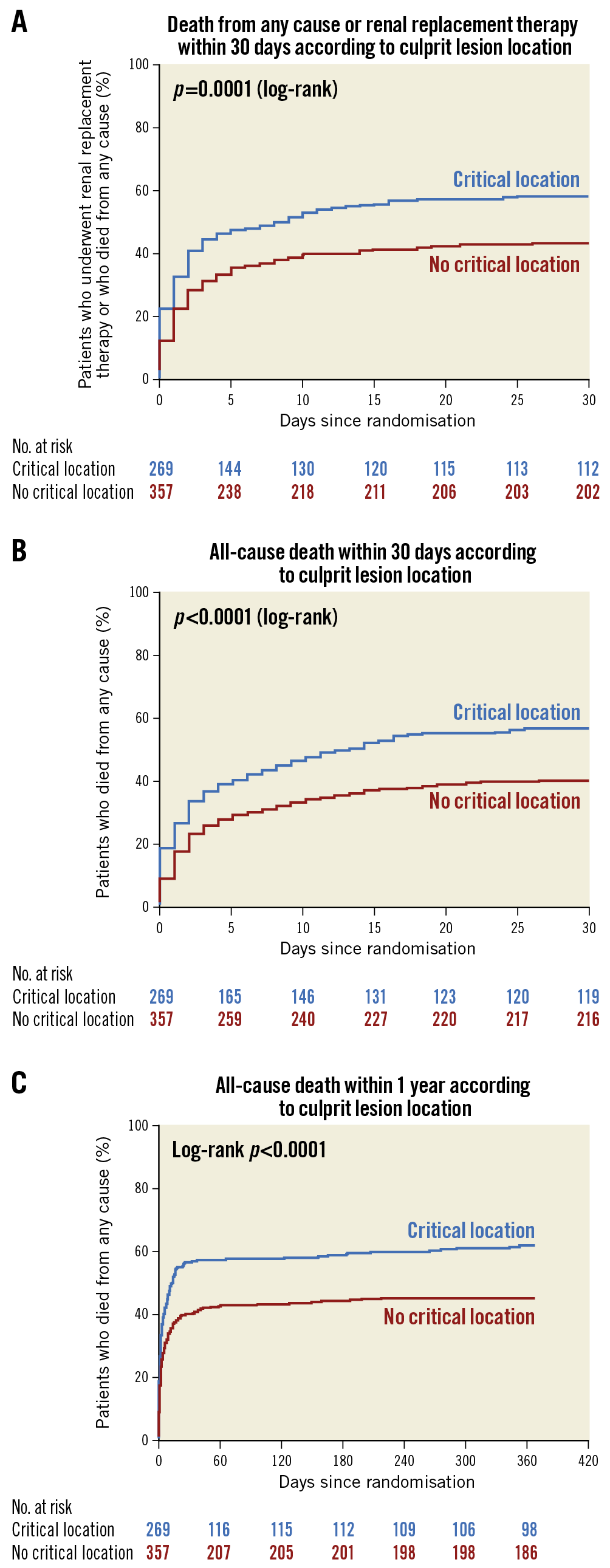

Results: A total of 269 (43%) out of 626 patients eligible for this analysis had a CCLL. Death or renal replacement therapy within 30 days, death within 30 days and death within one year were significantly higher in the CCLL than in the non-CCLL group (58.4% vs 43.4%, p<0.001, 55.8% vs 39.5%, p<0.001, 61.0% vs 44.5%, p<0.001, respectively). This was consistent after adjustment for baseline and angiographic characteristics. No interaction with the randomisation group (culprit lesion-only or immediate multivessel PCI) was found.

Conclusions: CCLL is frequent in CS and independently associated with worse clinical outcomes irrespective of the revascularisation strategy. Trial registration: www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT01927549

Introduction

Left main (LM) or proximal left anterior descending (LAD) are critical culprit lesion locations (CCLL) with impaired outcome in patients with myocardial infarction (MI)1,2,3,4. In cardiogenic shock (CS) complicating acute MI (AMI), the relationship between CCLL and outcome is controversial. In an analysis of the SHOCK trial5, a right coronary artery culprit was associated with superior survival in comparison to the LAD. In the IABP-SHOCK II trial6, a higher late mortality was observed in patients with distal culprit lesions, whereas no difference was observed for mortality with respect to the culprit lesion location itself. In patients with CS complicating AMI, the randomised trial entitled Culprit Lesion Only PCI versus Multi-vessel PCI in Cardiogenic Shock (CULPRIT-SHOCK)7,8 demonstrated that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the culprit lesion only, with the option of staged revascularisation of non-culprit lesions, was superior to immediate multivessel PCI with respect to a composite endpoint of death or renal replacement therapy at 30 days. The aim of this CULPRIT-SHOCK substudy was to assess whether CCLL identifies a group of patients with poorer prognosis independently of baseline and other angiographic characteristics.

Methods

This is a post hoc analysis of the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial, whose design and results have been described previously7,8,9. Briefly, the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial was a randomised, open-label study conducted at 83 European centres where 686 patients presenting with acute MI and multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD) complicated by CS were randomised, in a 1:1 ratio, to a strategy of culprit lesion-only PCI (with optional staged revascularisation) or immediate multivessel PCI between April 2013 and April 2017. Patients who initially underwent culprit lesion-only PCI had lower rates of death or renal replacement therapy at 30 days compared to patients who underwent immediate multivessel PCI. The investigation was approved by the ethics committee or institutional review board of each participating centre. The CULPRIT-SHOCK trial was supported by a grant agreement (602202) from the European Union Seventh Framework Program and by the German Heart Research Foundation and the German Cardiac Society.

STUDY POPULATION

All patients of the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial with a core laboratory identification of the culprit lesion were included. Patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) were excluded. The choice was taken to exclude patients with a prior CABG to obtain a homogenous AMI-related CS population – culprit lesion location on native vessels only. Prior CABG is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes in AMI-related CS10,11,12. The population with AMI-related CS and prior CABG is older, has extensive CAD and more often suffers from heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in comparison with those with no prior CABG, as shown in Vallabhajosyula’s 16-year cohort12. The mechanisms of AMI and CS in previous CABG recipients may be different in comparison to patients without prior CABG, with a high prevalence of acute occlusion of venous bypass grafts and pre-existing left ventricular dysfunction13. Furthermore, it is difficult to define a critical lesion location on CABG considering the great variety of CABG surgeries. Finally, only a minority of patients (33 out of 686 [4.8%]) had a prior CABG in the CULPRIT-SHOCK study.

ANGIOGRAPHIC CORE LABORATORY PROTOCOL

All coronary angiograms and PCI were independently reviewed at the core laboratory of the ACTION Study Group (Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France). CCLL was defined as a culprit lesion with a >70% diameter stenosis of the LM or LM equivalent (defined as >70% diameter stenosis of both proximal LAD and proximal left circumflex), proximal LAD or last remaining vessel. The last remaining vessel was defined as a sole remaining artery with chronic occlusion of the two other territories. PCI is known to be risky in patients whose coronary circulation depends on a last remaining vessel14, and thus the last remaining vessel represents a critical lesion location. The objective was to determine whether CCLL were independently associated with short- and long-term outcomes. Outcomes of interest for this substudy were all-cause death or renal replacement therapy and all-cause death at 30 days and all-cause death at one year.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables were described as proportion and compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were described as median (Q1; Q3) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Event rates were compared using the chi-square test, as previously published7,8. Kaplan-Meier curves were also used to show event rates over time, with classification according to CCLL, and compared using the log-rank test. Patients without an event were censored at 30 days or one year.

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the independent association between CCLL and outcomes. In each model, CCLL was adjusted for baseline clinical and procedural characteristics possibly associated with outcomes in univariate analysis (p<0.2) (Supplementary Table 1).

Given that, in the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial, approximately 10% of randomised patients had crossover, sensitivity multivariable analyses adjusted on consistent covariates as well as the effective revascularisation procedure undergone by the patients were additionally performed.

Results are reported as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS release 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) statistical software.

Results

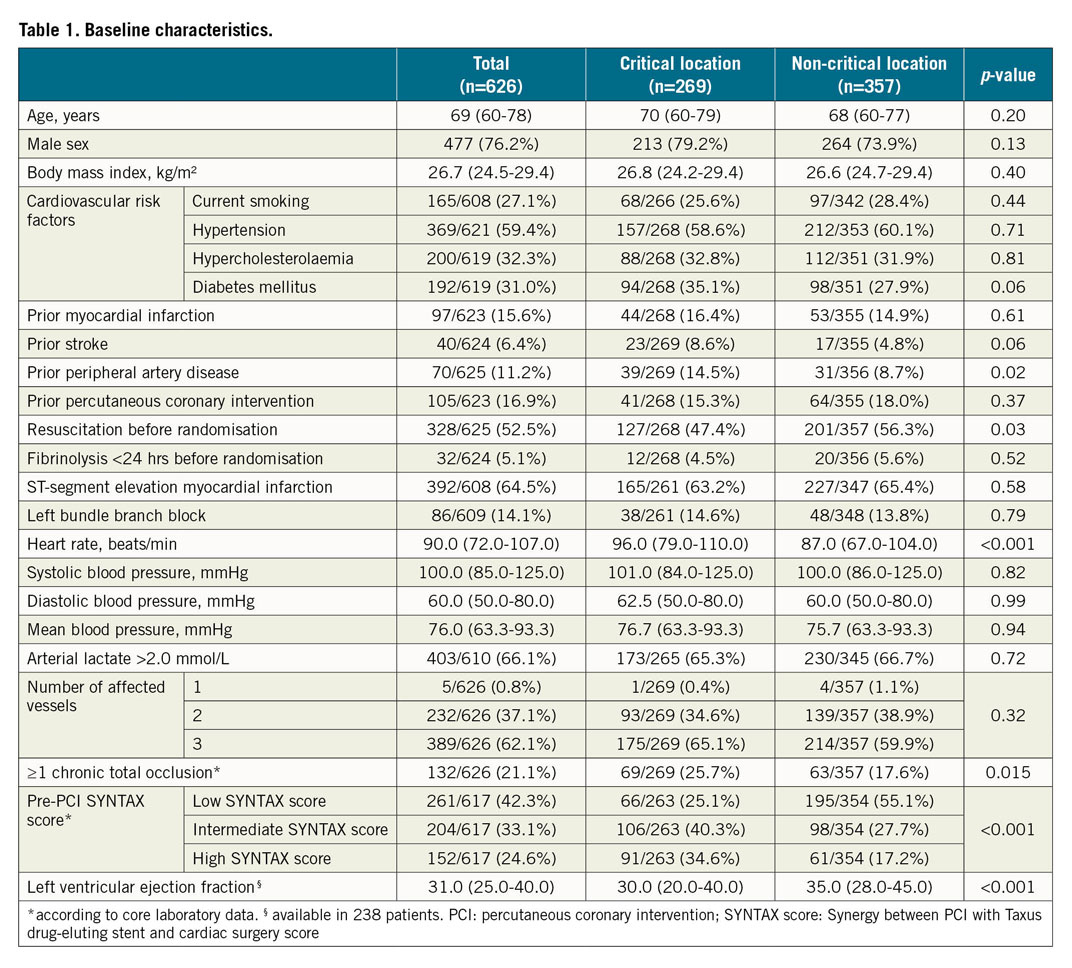

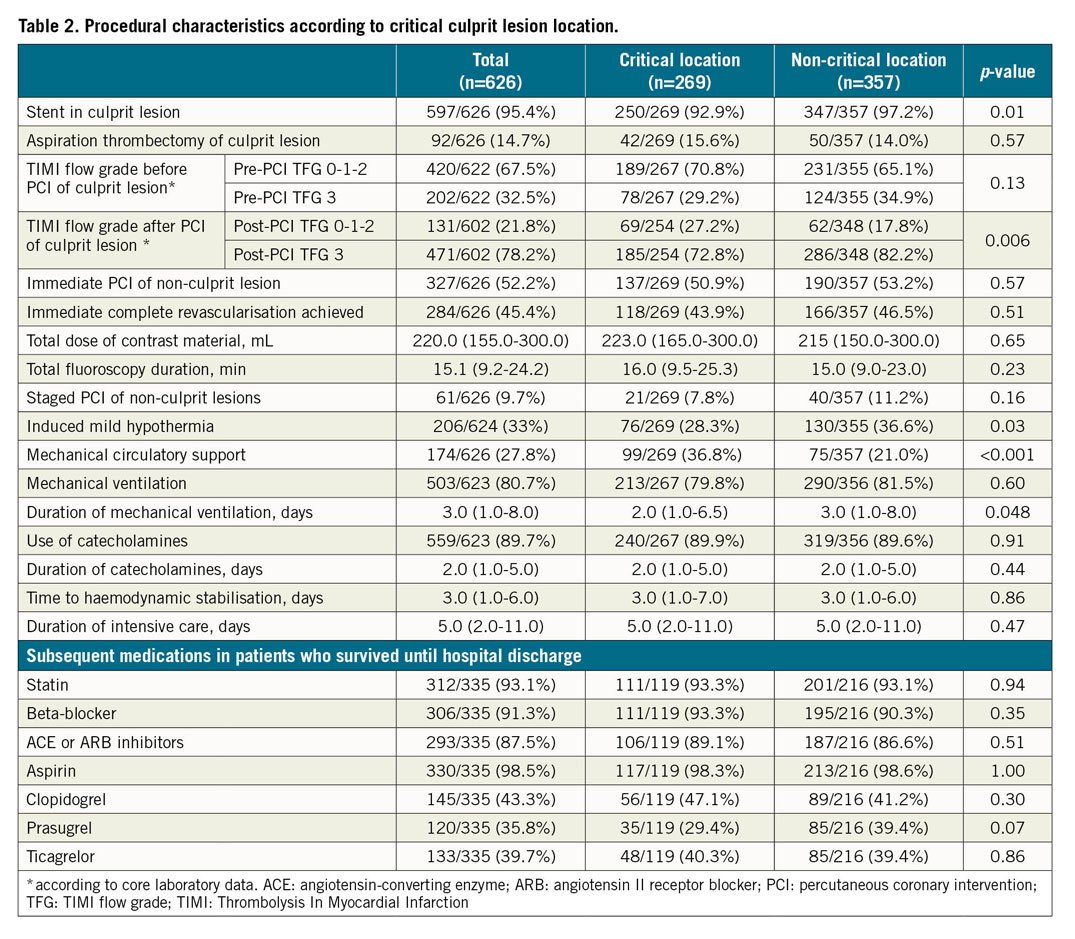

Of the 686 randomised patients with available informed consent, 33 patients were excluded because of prior CABG surgery, 8 patients had missing data concerning prior CABG status and 19 patients had no available core laboratory data. A total of 626 (91.3%) patients were finally included in this analysis, in whom a CCLL was found in 269 (43.0%) (Supplementary Figure 1). Thirty-eight patients (14.1%) had an LM lesion, 76 (28.3%) had an LM equivalent lesion, 148 (55%) had a proximal LAD lesion, and 7 (2.6%) had a last remaining vessel lesion. Baseline and procedural characteristics are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Patients with a CCLL had more chronic total occlusions, higher pre-PCI SYNTAX score, lower post-PCI Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade (TFG) 3 and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

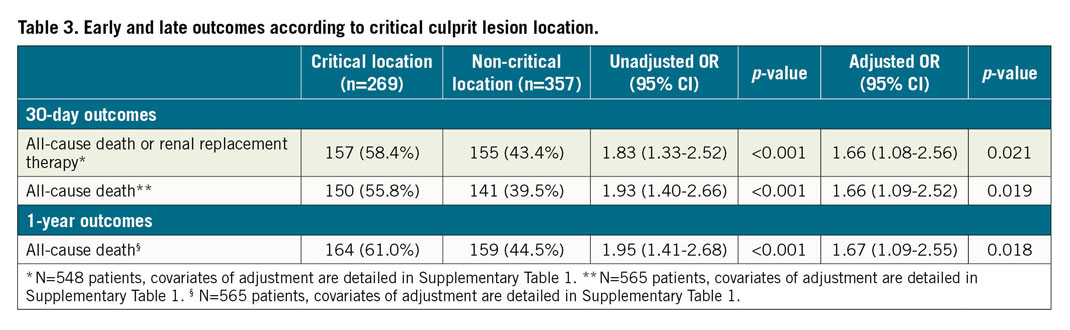

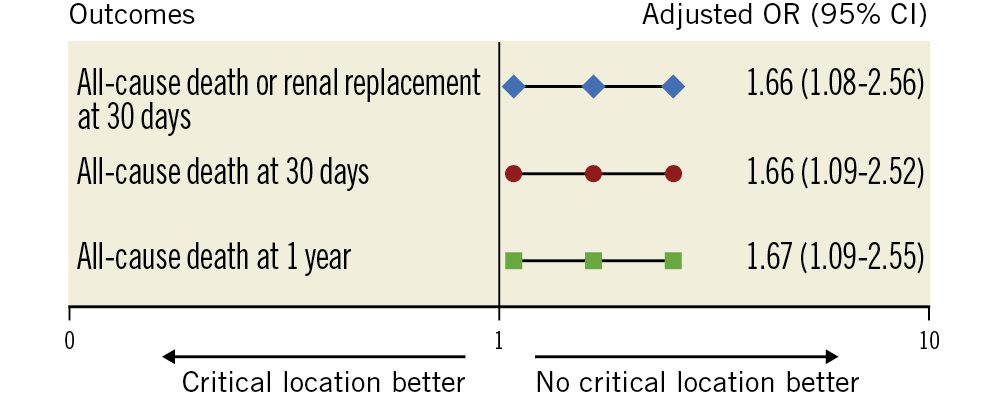

In the CCLL group, death or renal replacement therapy within 30 days, all-cause death within 30 days and death within one year were significantly higher than in the non-CCLL group (157 [58.4%] vs 155 [43.4%], p<0.001, 150 [55.8%] vs 141 [39.5%], p<0.001, 164 [61.0%] vs 159 [44.5%], p<0.001, respectively) (Table 3, Figure 1A-Figure 1C). These significant differences were consistent after adjustment (aOR=1.66 [1.08; 2.56], p=0.021, aOR=1.66 [1.09-2.52], p=0.019, and aOR=1.67 [1.09-2.55], p=0.018, respectively) (Figure 2). Results remained consistent in the sensitivity analysis adjusted for the revascularisation strategy (Supplementary Figure 2). Of note, no interaction with the randomisation group (culprit lesion-only or immediate multivessel PCI) was found for all outcomes (p=0.56, p=0.49 and p=0.11, respectively).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves. A) Death from any cause or renal replacement therapy within 30 days according to critical culprit lesion location. B) All-cause death within 30 days according to critical culprit lesion location. C) All-cause death within one year according to critical culprit lesion location.

Figure 2. Early and late outcomes according to critical culprit lesion location (covariates of adjustment are detailed in Supplementary Table 1).

No significant difference was found between each CCLL (LM, LM equivalent, proximal LAD, last remaining vessel) on all outcomes (p=0.88, 0.89 and 0.71 for death or renal replacement therapy within 30 days, death within 30 days and death within one year, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 3).

Discussion

Our results indicate that patients with AMI-related cardiogenic shock and a critical anatomic location of the culprit lesion have worse clinical outcomes than patients without such a critical location. They identify patients at higher risk of short- and long-term mortality, even after adjustment for confounding clinical and procedural characteristics.

In this core laboratory analysis, CCLL was defined as a culprit lesion with a >70% diameter stenosis of the LM, LM equivalent, proximal LAD or last remaining vessel. This anatomical marker is a strong determinant of a higher mortality compared with infarction in other vascular territories14,15,16,17,18. Thus, an LM equivalent lesion location should have an equivalent prognosis.

In contrast to the IABP-SHOCK II randomised trial and registry sub-analysis that shows no impact of culprit vessel type but an excess of mortality in case of distal culprit lesion location6, we found that patients with a CCLL had worse short- and long-term outcomes. A methodological difference between the IABP-SHOCK II study and the present study has to be mentioned. In the IABP-SHOCK II study, no comparison of mortality among the LM, proximal LAD and LM equivalent was provided. The increase in one-year mortality among patients with distal culprit lesions in this previous study was explained by higher rates of diabetes mellitus and known renal insufficiency in those patients. In the IABP-SHOCK II trial, the rates of post-PCI TFG 3 did not differ in patients with proximal or distal culprit lesions (81 vs 79%). The clinical impact of CCLL found in our study might not be related to the lower rate of post-PCI TFG 3 found in CCLL versus non-CCLL patients (73 vs 82%, p=0.006). Indeed, our results remain consistent after adjustment on post-PCI TFG; this implies that CCLL is a significant and independent predictor of worse outcome, information immediately available at the time of the coronary angiogram. Our results are consistent with other studies19,20,21,22,23 showing higher mortality rates for patients with an LM culprit lesion.

Patients with a proximal culprit lesion location may have a larger area at risk and a larger infarct size. The benefit of PCI would be expected to be more rapidly significant. Our results suggest that the initial excess risk associated with the critical location of the culprit lesion is not fully neutralised by revascularisation, and that these patients continue to be at higher risk of mortality after percutaneous revascularisation. In our study, LVEF was lower in the critical location group than in the non-critical location group (30.0% [20.0-40.0] vs 35.0% [28.0-45.0], p<0.001). Since no cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in this vulnerable population, no additional data on myocardial salvage index were available.

Post-procedural TIMI flow is a well-known independent prognostic factor in patients with MI and CS undergoing PCI21,24, whereas baseline SYNTAX score and residual SYNTAX score have no or limited added prognostic value over clinical assessment and risk scores25. In our analysis, the critical anatomic location increased the risk of death at 30 days and one year (aOR=1.66 and 1.67, respectively) independently of other reperfusion parameters of poor outcome such as post-PCI TIMI flow and independently of the extent of coronary disease as measured by the SYNTAX score also included in our model. An overall score to predict mortality based on clinical settings readily available at the time of CS diagnosis has been proposed26, which provides good discrimination of mortality risk in infarct-related CS. This kind of score, however, is mainly useful for clinical trials and not easy to use or widely used in clinical practice, whereas the CCLL is a simple and strong predictor of adverse outcome available in early CS management.

Limitations

Some limitations regarding this substudy of a randomised controlled trial have to be mentioned. First, only 626 patients (91.3%) out of 686 in the original study were eligible for this core laboratory sub-analysis. Second, the choice was made to exclude patients with a prior bypass graft (n=33, 4.8%). However, they represent a limited number of patients in our series and in real life. Finally, LVEF data were available for only 238 (38.0%) out of 626 patients and were therefore not accounted for in multivariate analysis. Other known predictors of poor outcome such as “arterial lactate >6 mmol/L” would have been relevant but there was also too much missing information (missing data: 36.3%). However, “arterial lactate >2 mmol/L” was included in the multivariate analysis, as well as “mechanical circulatory support”, “mechanical ventilation” and “catecholamine therapy”, which are known predictors of poor outcome and clinically relevant.

Conclusions

Among multivessel disease patients with acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock, critical culprit lesion location (LM, LM equivalent, proximal LAD or last remaining vessel) is independently associated with 30-day and one-year mortality. Critical culprit lesion location is a major prognostic marker, immediately available in multivessel disease patients with myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock.

|

Impact on daily practice Critical culprit lesion location (left main, left main equivalent, proximal left anterior descending or last remaining vessel) in patients with infarct-related cardiogenic shock and multivessel disease is frequent, immediately available and an independent prognostic marker of adverse outcome. |

Funding

The CULPRIT-SHOCK trial was supported by a grant agreement (602202) from the European Union Seventh Framework Program and by the German Heart Research Foundation and the German Cardiac Society. The current substudy was led by the ACTION Study Group at the Institute of Cardiology of Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (www.action-coeur.org).

Conflict of interest statement

E. Vicaut reports receiving personal fees from Eli Lilly; consultancy from Pfizer, Sanofi, LFB, Abbott, Fresenius, Medtronic, and Hexacath; being a member of the data safety monitoring board for CERC; lecture fees from Novartis, and grants from Boehringer and Sanofi. G. Montalescot has received research grants or consulting fees from Abbott, Amgen, Actelion, American College of Cardiology Foundation, AstraZeneca, Axis-Santé, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical, Brigham Women’s Hospital, China Heart House, Daiichi Sankyo, Idorsia, Elsevier, Europa, Fédération Française de Cardiologie, ICAN, Lead-Up, Medtronic, Menarini, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Partners, Pfizer, Quantum Genomics, Sanofi, Servier, and WebMD. U. Zeymer has received research grants or consulting fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Idorsia, The Medicines Company, Medtronic, MSD, Pfizer, Quantum Genomics, Sanofi, Servier, and WebMD. M. Zeitouni has received research grants from Institut Servier and Federation Française de Cardiologie. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.