Abstract

Aims: Percutaneous patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure seems to be effective for secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke in patients younger than 55 years of age. The efficacy in older patients remains uncertain. We compared the efficacy of PFO closure between patients younger and older than 55 years.

Methods and results: All 335 patients (mean age 50.2±12.6 years; 205 men) with cryptogenic thromboembolism who underwent PFO closure in our centres between 1998 and 2008 were included. Mean follow-up period was 4.2±1.9 years in the elderly (n=120) and 3.8±2.4 years in the younger patients (n=215) (p=0.15). Prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and coronary and peripheral artery disease was higher in the elderly (p<0.05 for all). Re-occurrence of stroke or TIA was higher in the elderly compared to the younger (annual event rate 2.4% versus 0.6%; log rank, p=0.005). Re-occurrence of stroke alone was higher in the elderly (annual event rate 1.2% versus 0.1%; log rank, p=0.01). Multivariate analysis showed that an age of >55 years was an independent predictor of recurrent stroke or TIA (HR 3.2, p=0.03).

Conclusions: Percutaneous PFO closure appears to be effective for secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke in younger patients but seems to be related with less beneficial outcome in elderly. Randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm our findings.

Introduction

The presence of a patent foramen ovale (PFO) has been associated with cryptogenic stroke1. This association has predominantly been found in patients younger than 55 years of age2-4. In several studies, percutaneous PFO closure has been shown effective for secondary prevention of cryptogenic thromboembolic events5-10. However, most of these studies concerned younger patients. Little is known about the recurrence rate of stroke and TIA in older patients with cryptogenic stroke with presumed thromboembolism undergoing PFO closure. Recently, Handke et al reported an association between the presence of a PFO and cryptogenic stroke in older patients11. These results seem to be in agreement with previous studies. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective analysis to determine the outcome of percutaneous PFO closure in older patients.

Methods

Study population

We included all consecutive 335 patients who were referred for percutaneous PFO closure because of a cryptogenic thromboembolic event between May 1998 and January 2008 in the St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, or the University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium. Of these patients, 120 (36%) were older than 55 years of age and 215 (64%) were younger. All patients were required to have suffered at least one cryptogenic thromboembolic event. The diagnosis of a cryptogenic thromboembolic event was made by the treating physician in the referring hospital. Other sources of systemic emboli had been ruled out according to local criteria. All neurological embolic events needed to be established by a neurological evaluation and, in the case of stroke, confirmed by the appropriate cerebral imaging studies. The presence of a right-to-left shunt (RLS) through a PFO was diagnosed by a contrast (agitated saline) transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with Valsalva-manoeuvre. An atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) was defined as a bulging of the atrial septum of at least 10mm. The presence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and comorbidities was retrieved from medical records. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the local ethics committee.

PFO closure

As previously reported, the PFO closure was performed according to standard techniques, under general anaesthesia and continuous TEE monitoring and concomitant biplane fluoroscopic guidance8,10. The choice of the device type was made in accordance to the clinical preference of the interventional cardiologist, depending on the anatomy of the PFO. An Amplatzer® device (AGA Medical Corporation, Golden Valley, MN, USA) was used in 62 patients (19%), a Cardioseal/Starflex® device (NMT Medical, Inc., Boston, MA, USA) in 85 patients (25%), a PFO Star® generations 1-3 device (Cardia, Eagan, MN, USA) in 159 patients (48%), an Intrasept® device (Cardia, Eagan, MN, USA) in 13 patients (4%), a Premere® device (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) in 13patients (4%), and a Helex® device (W.L.Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) in three patients (1%).

All patients were treated with antiplatelet therapy prior to the closure procedure. A bolus of 5000 U of heparin was administered after accessing the right femoral vein and each patient received an intravenous prophylactic dose of antibiotics at the time of the procedure. All patients were discharged on aspirin 100 mg once a day for a period of six months and clopidogrel 75 mg once a day during one month. Patients on oral anticoagulant therapy before the procedure were discharged on a combination of oral anticoagulant therapy and clopidogrel for one month.

Follow-up evaluation (outcome, complications, and efficacy)

We compared all follow-up data after PFO closure between patients older and younger than 55 years at closure. Follow-up information was obtained by review of the medical records and a phone call to the patients.

The primary endpoint was defined as re-occurrence of stroke, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), or any other thromboembolic event. The diagnosis of a recurrent event was made by the treating physicians. Neurological embolic events needed to be established by a neurological evaluation and, in case of stroke, confirmed by the appropriate cerebral imaging studies.

Periprocedural and long-term complications related to PFO closure were noticed and retrieved from the patients’ records. Complications were categorised into major and minor, according to the classification used by Khairy et al12.

Efficacy of PFO closure was defined as the absence of residual shunting, based on a contrast TEE or TTE study performed six months after closure. Residual shunting was defined as the appearance of any contrast bubble in the left atrium after injection of contrast and an adequately performed Valsalva-manoeuvre.

Statistical analysis

Patients were grouped according to their age (younger or older than 55 years). Descriptive statistics were used to report patients’ characteristics. Continuous variables were tested on normality and, if present, reported by mean±standard deviation (SD). Percentages were used to report categorical variables. Nominal data were compared using the Chi-square test. Continuous data were compared using the unpaired, two-sided Student’s t test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was done on the primary endpoint. Log-rank test was used to compare the occurrence of the primary endpoint between the groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox-regression analyses were used to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The three best characteristics that affected the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable models. For these analyses, the risk factors for cardiovascular disease were grouped as having none, one, or two or more risk factors. All tests were two sided and p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS Inc., version 12.0 for Windows.

Results

Patient characteristics

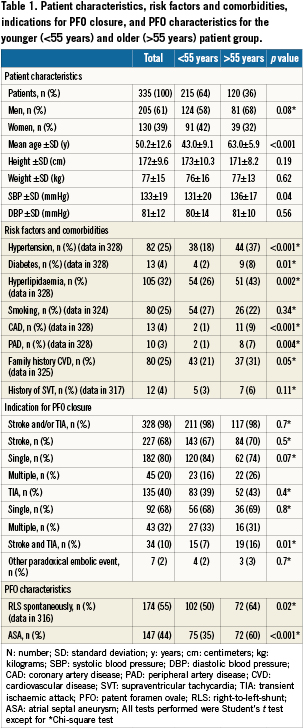

Between May 1998 and January 2008 335 patients (mean age 50.2±12.6 years; 205 [61%] men) underwent percutaneous PFO closure in our centres. Of these, 120 (35%) patients were older than 55 years of age (mean age 63.0±5.9 years) and 215 (64%) patients were younger (mean age 43.0±9.1 years). Baseline and PFO characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, and indication for closure are summarised in Table1. In seven patients (2%), a non-neurological paradoxical embolic event was the indication for PFO closure: one patient with a myocardial infarction, three patients with renal infarctions and three with peripheral limb embolisation. Different devices were used for PFO closure without difference between both age groups.

Follow-up evaluation

Outcome

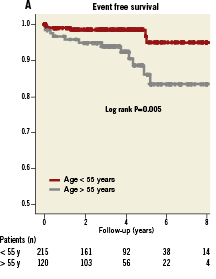

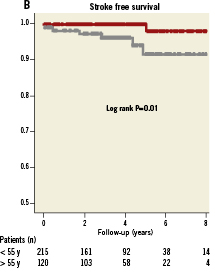

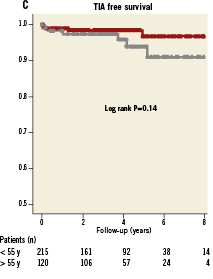

The mean follow-up time of all patients was 4.0±2.2 years. Mean follow-up time for patients older than 55 years was 4.2±1.9 years, as compared to 3.8±2.4 years for the younger age group (p=0.15). The primary endpoint (recurrence of stroke, TIA or any other thromboembolic event) occurred in 17 patients (5.1%; annual event rate 1.3%). In the older age group 12 patients (10%) reached the primary endpoint, resulting in an annual event rate of 2.4%: six patients (5%) suffered from recurrent stroke (annual event rate 1.2%) and another six (5%) developed a TIA (annual event rate 1.2%). In the younger age group, five patients (2.3%) reached the primary endpoint, resulting in an annual event rate of 0.6%: one patient (0.5%) suffered a recurrent stroke (annual event rate 0.1%) and four patients (1.9%) a TIA (annual event rate 0.5%). The event free survival for the primary endpoint was significantly better in the younger age group when compared to the older age group (log rank test, p=0.005). The event free survival for stroke was also better in the younger age group when compared to the older age group (log rank test, p=0.01). The recurrence of TIA did not differ significantly between the two groups (log rank test, P=0.14). Kaplan Meier curves are plotted in Figure1.

Figure 1. A) Kaplan Meier event free survival curves for patients older and younger than 55 years of age. B) Kaplan Meier stroke free survival curves for patients older and younger than 55 years of age. C) Kaplan Meier TIA free survival curves for patients older and younger than 55 years of age. For Kaplan Meier curves, follow-up was limited to a maximum of eight years.

In univariable analysis, age >55 years, a history of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) prior to PFO closure, the presence of two or more cardiovascular risk factors and the presence of multiple paradoxical embolic events prior to PFO closure were found to be predictors of the primary endpoint. In multivariable analysis, age >55 years remained a predictor of the primary endpoint (HR 3.2; 95% CI 1.1-9.1; p=0.03).

During follow-up four patients (3.3%) in the older age group and six patients (2.8%) in the younger age group died (log rank test, p=0.92). One death could have been device-related. This concerned a 53-year-old woman who died because of recurrent stroke. Echocardiography during follow-up revealed left atrial thrombus and device-thrombus for which coumadin had been started. These thrombi might have been the embolic source and cause of death.

Complications

Predefined overall complications of PFO closure occurred in 52patients (15.5%) with no significant difference between the elderly (18.3%) and the young (14.0%) (p=0.29). Complications included periprocedural (13.1%) and long-term (3.6%) complications and mainly consisted of minor complications, mostly transient atrial fibrillation (8.7%). Only three (0.9%) were major complications and included the following cases: in a 60-year-old man, an Amplatzer 28mm device did not unfold properly. While trying to retrieve it, it was lost in the inguinal subcutis making minimal invasive surgery necessary. In a 54-year-old woman, a Premere 25mm device embolised to the pulmonary artery. She was successfully treated by percutaneous retraction of the device and implantation of a second device. The third patient, a 53-year-old man, suffered a cardiac tamponade after PFO closure with a PFO STAR 33mm device, probably due to perforation of the device. He was treated surgically and the device was extracted.

Efficacy

At six-months follow-up, 281 patients (83.9%) underwent a TTE or TEE to diagnose residual shunting after PFO closure. The presence of residual shunting was 9.3% in the entire study population with no significant difference between the older (12.1%) and the younger age group (7.7%), p=0.22.

Discussion

Our findings confirm that percutaneous PFO closure in patients with a history of paradoxical embolism appears to be effective for prevention of recurrent stroke and TIA in patients younger than 55years. Recurrence was significantly higher in the older patients’ group, suggesting that either percutaneous PFO closure may be less beneficial in elderly or that they constitute a high risk population.

PFO closure and recurrent thromboembolism

Patients with cryptogenic strokes related to a PFO are at risk for stroke recurrence13-16. Percutaneous PFO closure has been shown effective in the prevention of recurrent thromboembolism5-10,17. Inareview article, Khairy et al reported a one-year rate of recurrent neurologic thromboembolism of 0% to 4.9% with transcatheter intervention as compared to 3.8% to 12.0% with medical treatment12. However, randomised trials that compare medical treatment and transcatheter closure are still lacking.

We found a yearly recurrence rate of stroke, TIA or any other thromboembolic event of 1.3% in 335 patients during a mean follow-up time of 4.0±2.2 years which is low and comparable with previous reports.

PFO closure and recurrent thromboembolism in the elderly

To date, there have been only a few reports that address the outcome of older patients with cryptogenic thromboembolism who have undergone transcatheter PFO closure. Kiblawi et al found no significant differences in the rate of recurrent stroke or TIA in 184 patients older than 55 years (mean age 66.9±8.3 years) as compared to 272 younger patients (mean age 41.1±7.7 years) after PFO closure with a Cardioseal Septal Occluder®18. Annual recurrence rates were 1.1% and 1.0% respectively during a mean follow-up of 17.8±11.1 months. Spies et al compared the outcome of PFO closure in 423 elderly (median age 63 years, range 56-88) and 632 younger patients (median age 42 years, range 14-55)19. They found a similar annual incidence of recurrent thromboembolism in both groups during a median follow-up time of 18 months, 1.8% in elderly compared to 1.3% in younger patients. Finally, Wahl et al evaluated 525 patients with a median age of 52 years (range 16-79) who underwent PFO closure and found a low annual recurrence rate of thromboembolic events of less than 2%20. In this study, older age (>55 years) did not adversely affect outcome.

In contrast to these earlier reports, our study is the first to describe a significant difference in the outcome of percutaneous PFO closure in older patients as compared to younger patients. We found an annual recurrent rate of 2.4% for stroke or TIA and 1.2% for stroke alone in patients older than 55 years, as compared to an annual recurrent rate of 0.6% for stroke or TIA and 0.1% for stroke alone in patients younger than 55 years (log rank test, P=0.005 for recurrent stroke and TIA and P=0.01 for recurrent stroke). The mean follow-up time (4.0±2.2 years) in our study was longer than in the studies described above. As our Kaplan-Meier curves indicate, many events in the older patient group occurred during longer-term follow-up, which could be an explanation for our findings compared to earlier reports. Although an annual recurrence rate of 2.4% of stroke or TIA in the older patients is low compared to previous reports of PFO closure and medical treatment12, it remains significantly higher than the recurrence rate we found in the younger patients. Additionally, age above 55 years was an independent predictor of recurrent stroke or TIA (HR 4.0, p=0.009 in univariate analysis and HR 3.2, p=0.03 in multivariate analysis). This can be explained in a variety of ways. Firstly, it could be due to residual shunting after PFO closure. We found that residual shunting, although not significantly, was slightly higher in the older age group. Residual shunting after PFO closure has been described as a predictor for recurrent thromboembolism10,20. Moreover, it could be that venous thrombogenesis is higher among patients >55 years21-23, leading to a higher chance of thromboembolism in the presence of residual RLS. Secondly, a recurrent event after PFO closure might have another cause than paradoxical embolism. The higher event rate in the older age group might be due to systemic atherosclerosis. As indicated in Table1, the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and coronary and peripheral artery disease was higher in the older age group. Having two or more risk factors for atherosclerosis was associated with recurrence of stroke or TIA by univariate analysis. Thirdly, the incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) is higher at older age24. This is associated with stroke and TIA in this age group25. Kiblawi et al found a higher incidence of new onset AF in elderly who underwent a percutaneous PFO closure, compared to younger patients18. In our study, new onset AF was only slightly higher in the older age group (9.2%) compared to the younger age group (8.4%). However, there could have been a higher incidence of asymptomatic and undetected AF in the elderly. Moreover, we found a history of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) to be associated with recurrent stroke and TIA in univariable analysis. Patients with a history of SVT are probably at higher risk for developing new onset AF after PFO closure, leading to recurrent neurological events. Moreover, there could be other (unmeasured) confounding factors that cause a recurrent stroke or TIA, especially in older patients.

The annual recurrence rate of stroke or TIA after medical treatment in elderly with a cryptogenic stroke and a documented PFO is 10%26. We found an annual recurrence rate of stroke or TIA of 2.4% in elderly who underwent a PFO closure for a cryptogenic embolic event. Hence, the transcatheter PFO closure might have beneficial effects in both younger and older patients with cryptogenic thromboembolism, but the higher recurrence rate of stroke or TIA in older patients compared to younger patients might be attributable to other factors.

Complications

In a systematic review describing ten transcatheter PFO closure studies, the minor and major complication rates were 7.9% and 1.5% respectively12. We found a total complication rate of 15.5%. However, only 0.9% were major complications. An explanation for the high minor complication rate could be that we counted all new episodes of transient AF as a complication of PFO closure during the entire follow-up period. Transient AF accounted for 56% of all complications. It is not certain, whether the occurrence of AF at long-term follow-up is related to PFO closure.

We found no difference in the occurrence of complications between the two age groups (18.3% for the elderly and 14.0% for the young), which is comparable with the results of the study conducted by Kiblawi et al in which a minor complication rate of 3.8% for the older patients is described as compared to 4.4% for the younger. Moreover, during follow up 22% of the elderly suffered atrial arrhythmias compared to 17% of the younger. However, the incidence of new-onset AF was significantly higher in the older patients (7.6%) as compared to the young (0.7%) (p<0.025)18.

Efficacy

Reports about residual RLS after PFO closure are conflicting and range from 4 to 49%. This might be due to differences in device types, follow-up time, and methods used for diagnosing residual shunting5,7,8,10,27,28. Kiblawi et al found no difference in the occurrence of residual shunting as diagnosed by TTE six months after PFO closure between patients older and younger than 55 years (2.3 vs. 2.8%)18. Spies et al also found no difference in residual shunting between the elderly (10%) and the young (8.4%) based on a TEE, TTE or transcranial Doppler study performed at least six months after PFO closure19.

In our study, residual RLS was not significantly higher in the older age group (12.1%) as compared to the young (7.7%).

Limitations

The study has a retrospective design and there might be referral bias. The diagnosis of cryptogenic thromboembolic events was made by the referring physicians and there might be no uniform evaluation. The residual RLS detection was not obtained in all patients, and different imaging techniques (TTE and TEE) were used to detect RLS. Both over- and underestimation are possible29. However, this is inherent to the retrospective character of the study. Another limitation is the lack of a control group of patients treated medically. All patients were referred for PFO closure after the occurrence of a cryptogenic embolic event, and none of them wanted to leave the PFO unclosed. By multivariable analysis we tried to adjust for most factors, however, there remain some unmeasured confounders. Hence, recurrent events in the elderly group might not be due to reduced effectiveness of PFO closure since the mechanism of recurrence could be not related to the PFO. As already described, our data do not answer the important remaining question of how transcatheter PFO closure compares to medical treatment for prevention of recurrent thromboembolism. The results of ongoing randomised trials (CLOSURE-1, PC, RESPECT) will hopefully answer this question. Unfortunately, a common exclusion criterion for most ongoing trials is age above 60 years. Randomised trials that include older patients are needed to develop management strategies in this large patient group.

Conclusion

Percutaneous PFO closure appears to be effective for secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke in younger patients, but seems to be related to less beneficial outcome in the elderly. Randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm our findings, and to study whether PFO closure has a reduced efficacy in older patients.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.