Increased stent thrombosis rates in the ABSORB clinical trials have hampered use of bioresorbable scaffolds (BRS)1. The manufacturer’s subsequent removal of the product led to a loss of trust and interest in the technology, with many practitioners ascribing stent thrombosis risk to all BRS technologies. In addition, recently updated European guidelines downgraded the usage of BRS technology to class III level C, stating that “BRS are currently not recommended for clinical use outside of clinical studies”2, nearly putting the final nail in the coffin for clinical use of BRS technology. This “class effect” fails to account for the improved features of a range of devices, including magnesium scaffolds and refinements in poly-L-lactic acid-based BRS technology. Consequently, we may have sounded the death knell too soon on this technology, depriving our patients of the emerging benefits of these devices.

Early BRS technologies required increased strut thickness and width to match the radial strength of contemporary drug-eluting stents (DES). First-generation devices, such as the Absorb™ (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA), have 150 µm thick struts, resulting in increased flow disturbances, thrombogenicity, and adverse outcomes3. In recent years, BRS development has focused on refinements in stent design and deployment technique. Growing evidence shows that improved techniques, such as predilation, sizing, post-dilation (PSP) with BRS, or the four Ps (patient selection, proper sizing, predilatation, post-dilatation) with magnesium scaffolds, provide results on a par with DES without the initially reported hazard of scaffold thrombosis4,5. A recent pooled analysis of the ISAR-Absorb MI and ABSORB STEMI TROFI II trials showed that the Absorb scaffold demonstrated similar clinical performance to its everolimus-eluting stent comparator in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients6. A similar pattern was seen in the recent MAGSTEMI trial, with low rates of scaffold thrombosis in each group7. Large-scale registry data also appear to mirror this trend, with the recent BIOSOLVE-IV data showing 0.3% scaffold thrombosis at 36 months8.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Chieffo et al provide hope that these changes are beginning to bear fruit9.

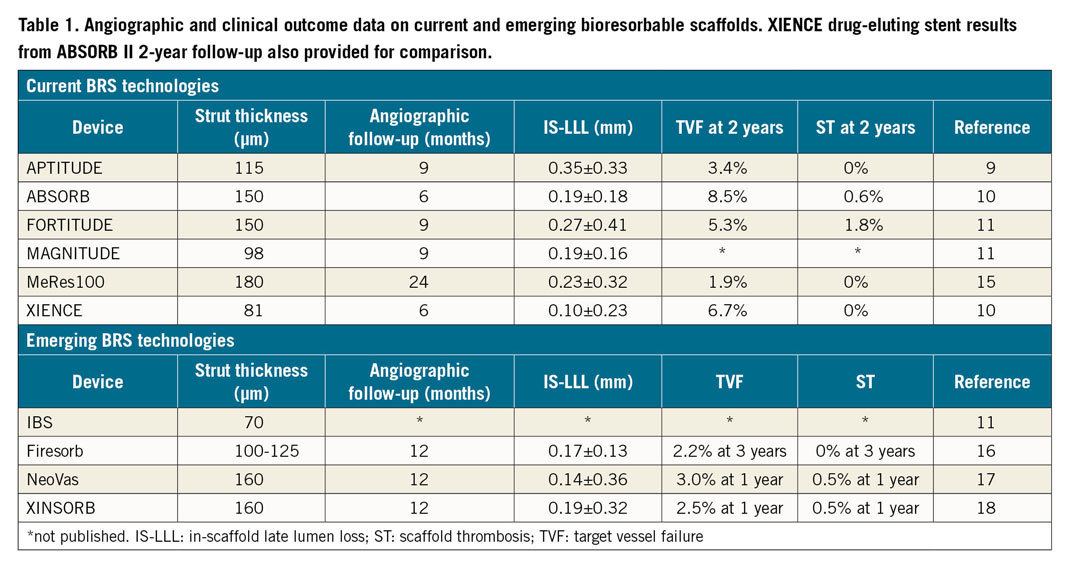

Their prospective, international, first-in-human study examined the rates of in-scaffold late lumen loss (IS-LLL) and target vessel failure (TVF) of the sirolimus-eluting, ultrahigh-molecular-weight, 115 µm APTITUDE® BRS (Amaranth Medical Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The RENASCENT II study demonstrated rates of IS-LLL comparable to other sirolimus-eluting, lactate-polymer BRS technologies (Table 1). The APTITUDE BRS demonstrates a similar pattern – close but not quite on target. Also notable is the 0% rate of target lesion revascularisation, TVF and scaffold thrombosis at two years. When compared to two-year ABSORB II data10 (Table 1), the RENASCENT II data demonstrate numerically superior rates of TVF and scaffold thrombosis. This is despite both scaffolds showing similar resorption periods, with greater than 85% scaffold degradation at 18 months and complete resorption at 24 months11.

Besides scaffold design improvements, the RENASCENT II study highlights these key aspects in relation to BRS technologies: patient and lesion selection, implant technique, and long-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

Compared to traditional stents, BRS technology requires more careful consideration of patient selection and lesion characteristics. Previous studies demonstrated that TVF and stent thrombosis rates in BRS are adversely affected in STEMI12, longer lesion lengths13, severe vessel calcification14, and vessel sizes less than 2.25 mm or greater than 3.75 mm13. The current trial’s design excluded these high-risk groups, indicating that we might be closer to finding the correct niche for BRS – stable patients with simple, discrete, de novo lesions.

Besides knowing where BRS are best suited, the optimal implant strategy has emerged. The 60 patients enrolled in the RENASCENT II study underwent a rigorous implantation technique with proper image-guided vessel sizing, mandatory lesion preparation, post-deployment imaging, and high post-dilatation rates. These steps, absent in early ABSORB trials because of concerns about scaffold fracture, demonstrated improved outcomes up to three years4 and have become the standard technique for BRS technologies.

Lastly, tailoring DAPT to the scaffold resorption period plays a key role in preventing stent thrombosis. In ABSORB II, 36% remained on DAPT at two years, compared to 44% in RENASCENT II. The increased use of prolonged DAPT in RENASCENT II highlights our better understanding of mitigating scaffold thrombosis risk during the absorption period13.

The RENASCENT II trial highlights not just the success of the APTITUDE BRS, but also success in incorporating evidence from previous trials. This shows the field’s continued evolution. With the Absorb programme’s setbacks, the road to building trust in BRS technology is challenging. Increasingly thinner struts, such as the MAGNITUDE® (98 µm) and DEFIANCE™ (85 µm) platforms (both Amaranth Medical Inc.), or other BRS technologies currently undergoing clinical trials in Asia (Table 1), may restore trust in BRS technologies. Ultimately, we need well-powered randomised controlled clinical trials for BRS technology to re-enter clinical practice. Those designing these trials must give careful thought to the comparator group (for example, DES versus drug-coated balloons), inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the future role of BRS in the landscape of percutaneous coronary intervention.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Waksman is a member of the advisory board of Amgen, Boston Scientific, CardioSet, Cardiovascular Systems Inc., Medtronic, Philips, and Pi-Cardia Ltd., is a consultant for Amgen, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CardioSet, Cardiovascular Systems Inc., Medtronic, Philips, and Pi-Cardia Ltd., has received grant support from AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Chiesi, is on the speakers bureau of AstraZeneca, and Chiesi, and is an investor in MedAlliance. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.