Abstract

Aims: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) represents a valid therapeutic alternative for patients with severe aortic stenosis at high surgical risk. However, there is no general consensus regarding the role of anaesthesia in TAVI management. The goal of this clinical project was to assess the safety and non-inferiority of local anaesthesia (LA) versus general anaesthesia (GA) in a large cohort of patients undergoing TAVI.

Methods and results: All 1,316 consecutive patients who underwent TAVI at seven high-volume Italian centres were enrolled. The anaesthetic regimen consisted of GA in 355 (26.9%) patients or LA in 961 (73.0%) patients. Baseline demographics were similar between the two groups except for a higher median logistic EuroSCORE (p=0.004) and peripheral artery disease (p<0.001) in the GA group. The two groups showed similar device success with no significant difference in terms of mortality, stroke and myocardial infarction. The overall procedural time was longer with the use of GA (p<0.001). The LA group showed a lower incidence of major access-site complications (p=0.01) and major (p=0.03) and life-threatening bleedings (p<0.001) with a lower occurrence of acute kidney injury stage 3 (p=0.002). Consistently, we observed a significantly shorter length of hospital stay in LA patients (8 days [7-13] vs. 7 days [6-10], GA vs. LA; p<0.001). As the GA patients were found to be at higher risk due to a higher prevalence of peripheral artery disease we carried out a propensity matching to obtain two comparable groups. This sub-analysis confirmed the same results previously observed in the overall population. As expected, in the GA group we observed longer procedural time, higher use of a surgical vascular access, higher incidence of acute kidney injury stage 3 and higher rate of bleeding and major vascular access-site complications.

Conclusions: Our study indicates that, in experienced centres which have gone beyond their initial learning curve with TAVI, the use of local anaesthesia in a selected patient population can be associated with good clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, as severe procedural complications are possible, an anaesthesiologist should always be present as part of the team.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is currently considered a safe and effective treatment for patients with severe aortic stenosis at high surgical risk1-6.

At the beginning of TAVI experience, general anaesthesia (GA) with endotracheal intubation was generally performed due to the various clinical and procedural issues associated with the treatment of high-risk patients7-10. Recently, increasing operator experience and device improvement have led to a lower use of GA and a higher use of local anaesthesia (LA) according to patient and procedural characteristics8,10-12. However, data for TAVI under LA and the incidence of conversion to GA from LA during the procedure are limited.

In the present research we sought to assess the safety and efficacy of LA versus GA in a large cohort of patients undergoing TAVI.

Methods

PATIENT POPULATION

Starting from June 2007, all consecutive patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVI with the third-generation 18 Fr CoreValve® device (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were prospectively included in the ClinicalService Project. This is a nation-based clinical data repository and medical care project aimed at describing and improving the use of implantable devices in Italian clinical practice which has already been described elsewhere13,14. For the purposes of this evaluation we analysed 1,316 consecutive patients at seven Italian high-volume centres and with available and complete data on anaesthetic management. To evaluate the two strategies better, we performed a propensity match evaluation comparing the GA group with a comparable group of patients treated with LA.

ANAESTHETIC MANAGEMENT

The anaesthetic regimen consisted of GA or LA according to patient and procedural characteristics. GA was mostly performed at the beginning of the learning curve for the procedure and in patients who required demanding surgical vascular access, and in patients with congestive heart failure.

The general anaesthetic regimen consisted of a variable combination of a volatile agent or intravenous agent (sevofluorane or propofol), muscle relaxants (rocuronium or cisatracurium) and ultra-short-acting opioid (remifentanil). Alternatively, the procedure was performed using LA consisting of 1% lidocaine injected at the arterial access sites (femoral and/or subclavian). Additionally, an intravenous infusion with remifentanil or dexmetedomidine was administered when necessary in order to keep patients comfortable but cooperative and capable of controlling their airways.

DEFINITIONS

All of the information contained in the database was re-evaluated to assess the procedural results and clinical endpoints according to the definitions proposed by the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC)15,16.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean±standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, or as median and 25th-75th percentile (IQR) otherwise. Normality of distribution was tested by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Absolute and relative frequencies are reported for categorical variables. Continuous Gaussian variables were compared by means of a Student’s t-test for independent samples, while skewed distributions were compared using the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test. Differences in proportions were compared by applying a chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, and differences in in-hospital and 30-day outcomes were assessed using logistic regression. Time to long-term outcomes was described by means of the Kaplan-Meier curve and compared between groups by means of the log-rank test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To identify two comparable groups of patients undergoing LA and GA, respectively, we performed a propensity score analysis. A logistic regression model was fitted with the covariates that were statistically different in the original population to obtain the propensity scores for each observation. The stepwise selection was used to identify the best set of predictors among all the covariates. Finally, a total number of 255 patients who underwent GA were matched to 255 patients who underwent LA, using a greedy matching algorithm.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

PATIENT POPULATION

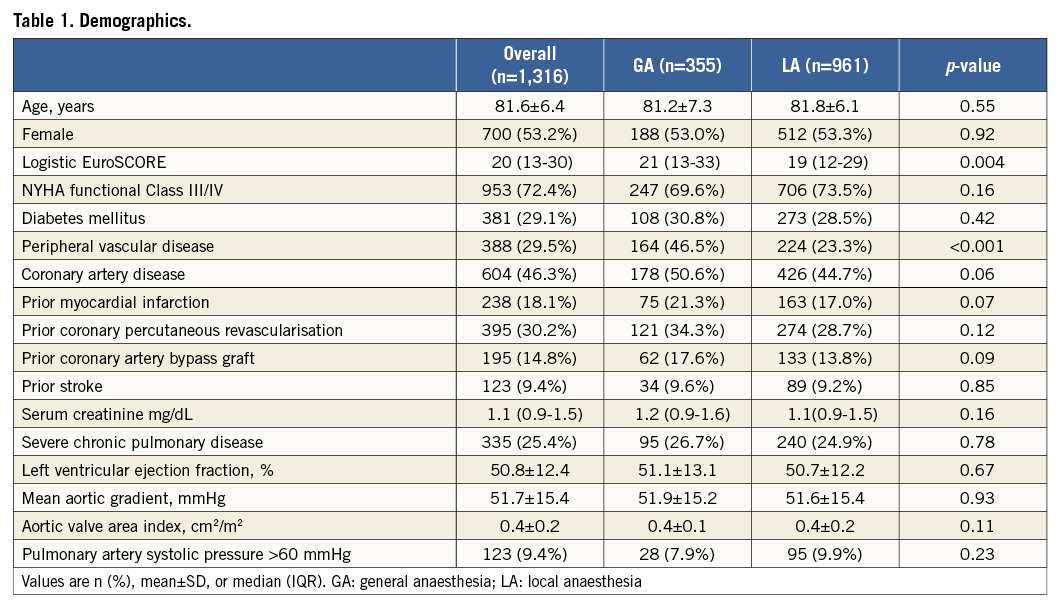

Between June 2007 and December 2012, 1,316 consecutive patients enrolled in the Italian Medtronic ClinicalService Project underwent TAVI using the 18 Fr third-generation CoreValve bioprosthesis. Baseline characteristics of the patient population are detailed in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 81.6±6.4 years, 53.2% (n=700) were female, and the median logistic EuroSCORE was 20% (13-30). The anaesthetic regimen consisted of GA in 355 (26.9%) patients or LA in 961 (73.0%) patients, according to patient and procedural characteristics. Baseline demographics were similar between the two groups. The GA group showed a significantly higher median logistic EuroSCORE (21% vs. 19%; p=0.004) and a significantly higher prevalence of peripheral artery disease (46.5% vs. 23.3%; p<0.001). There were no differences between these two groups in terms of echocardiographic variables (Table 1).

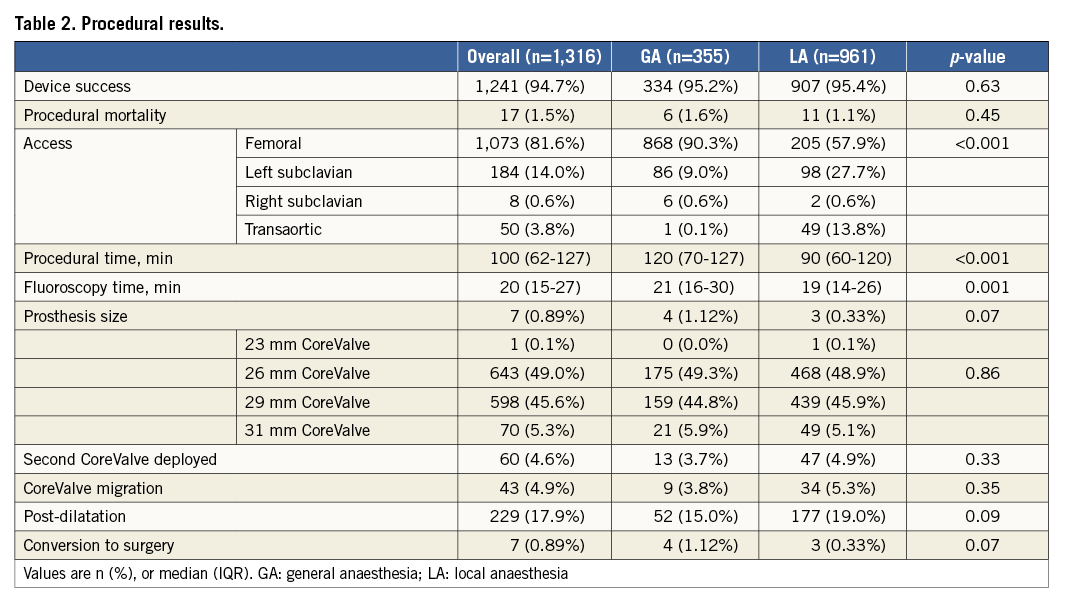

PROCEDURAL RESULTS

Procedural results are defined in Table 2. Device success was high in both groups (95.2% vs. 94.5%, GA vs. LA; p=0.63) with no difference in prosthesis size (p=0.86). Procedural and fluoroscopy time were longer in the GA group (120 min [70-127] vs. 90 min [60-120]; p<0.001, and 21 min [16-30] vs. 19 min [14-26]; p=0.001, respectively). The use of GA was significantly higher in patients treated with a surgical vascular access compared to those treated entirely percutaneously. In particular, among the 1,073 patients treated using the transfemoral approach, 868 (80.8%) patients underwent LA, and 205 (19.2%) patients underwent GA (p<0.001). Among the 242 patients treated via a surgical vascular access (trans-subclavian or transaortic), 93 (38.5%) underwent LA, and 149 (61.5%) patients underwent GA (p<0.001).

The rates of CoreValve-in-CoreValve implantation during the same procedure (3.7% vs. 4.9%; p=0.33) and of CoreValve migration (3.8% vs. 5.4%; p=0.35) were similar. Procedural mortality was very low in both groups (2.6% vs. 1.8%, GA vs. LA; p=0.46). Only four (2.1%) patients in the GA group and three (0.5%) patients in the LA group required conversion to surgery for uncontrolled pericardial effusion (p=0.06).

Of the 917 patients receiving LA and for whom we had available data about conversion to GA, only 27 (2.9%) patients required conversion to GA due to the occurrence of procedural complications or the lack of patient collaboration during the procedure.

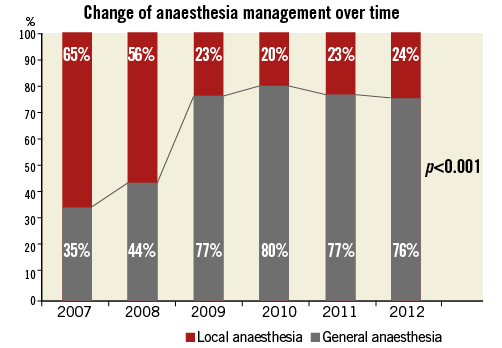

To evaluate the role of operator experience in the choice of the anaesthetic management, we compared the use of GA vs. LA for each year from June 2007 to December 2012. Greater experience was associated with a significant decrease in the use of GA over the years (65% 1st year, 56% 2nd year, 23% 3rd year, 20% 4th year, 23% 5th year and 24% 6th year, respectively, p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Anaesthetic management (general anaesthesia vs. local anaesthesia) according to increased operator experience over the years.

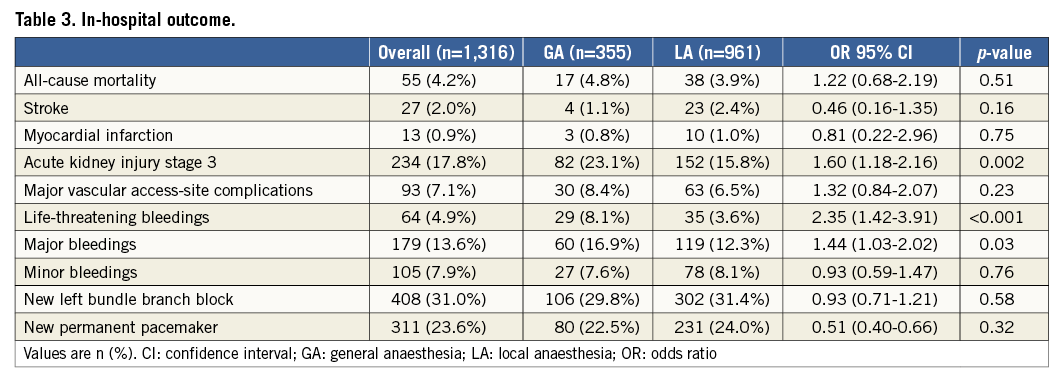

IN-HOSPITAL OUTCOME

In-hospital events are reported in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the incidence of in-hospital all-cause and cardiac mortality, neurological events, myocardial infarction, occurrence of new left bundle branch block and occurrence of new permanent pacemaker implantation. Of note, GA was associated with a higher incidence of acute kidney injury stage 3 (23.1% vs. 15.8%; p=0.002), life-threatening bleeding (8.2% vs. 3.6%; p<0.001) and major bleeding (16.9% vs. 12.4%; p=0.03).

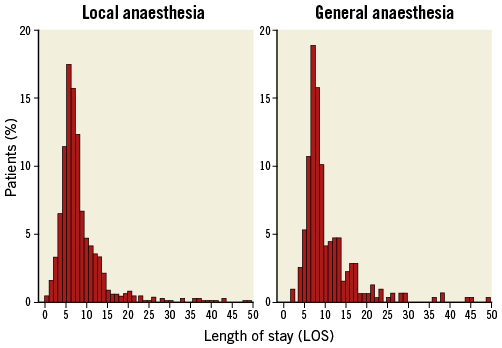

At the end of the procedure, all patients undergoing GA were routinely transferred to a cardiac surgical intensive care unit, whereas patients treated with LA were usually transferred to an intermediate care unit. Consistently, we observed a significantly shorter length of hospital stay among patients treated with LA (8 days [7-13] vs. 7 days [6-10], GA vs. LA; p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Length of stay distribution after TAVI procedure according to the anaesthetic management.

THIRTY-DAY AND LONG-TERM OUTCOME

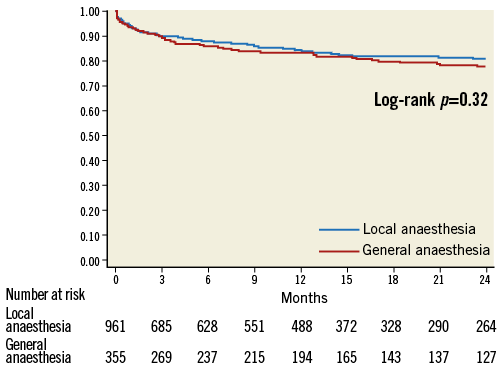

Thirty-day all-cause mortality (6.5% vs. 5.9%, GA vs. LA; OR [95% CI]: 1.10 [0.67-1.81], p=0.71) and cardiovascular mortality (5.3% vs. 4.5%; OR [95% CI]: 1.42 [0.76-1.62], p=0.27) were similar between groups. Two-year follow-up was available in 94.5% of patients, with survival status reported as of September 2013. Median follow-up was 13 months (ranging from three to 24 months) for the GA group and 12 months for the LA group (ranging from two to 24 months). The Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the two groups is shown in Figure 3. Survival estimates at two years were 77.6% in the GA group vs. 81.1% in the LA group (HR [95% CI]: 1.16 [0.86-1.56] p=0.32). Actual two-year mortality was 17.8% vs. 14.5%. The two-year Kaplan-Meier freedom from cardiac death was 88.1% vs. 90.5% in the GA vs. LA, respectively (HR [95% CI]: 1.23 [0.81-1.86] p=0.33). Actual two-year cardiac mortality was 9.3% vs. 7.3%.

Figure 3. Survival - Kaplan-Meier estimates of 2-year survival. Red line indicates general anaesthesia group; blue line indicates local anaesthesia group.

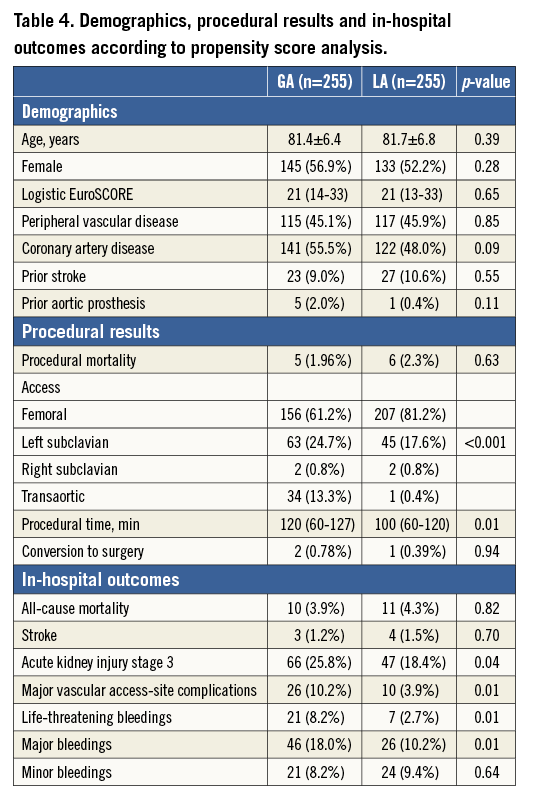

PROPENSITY SCORE ANALYSIS

We compared 255 patients undergoing GA to a propensity-matched cohort of 255 patients undergoing LA in the same period (Table 4). Baseline demographics were similar between the two groups. Procedural results were also similar except for longer procedural time and a higher use of a surgical vascular access in GA patients. Regarding in-hospital events, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the incidence of in-hospital all-cause and cardiac mortality, neurological events and myocardial infarction. GA was associated with a higher incidence of acute kidney injury stage 3 (25.8% vs. 18.4%; OR [95% CI]: 1.55 [1.01- 2.36] p=0.04), life-threatening bleeding (8.2% vs. 2.7%; OR [95% CI]: 3.18 [1.33-7.62] p=0.01), major bleeding (18.0% vs. 10.2%; OR [95% CI]: 1.94 [1.16-3.25] p=0.01) and major vascular access-site complications (10.2% vs. 3.9%; OR [95% CI]: 2.78 [1.31-5.90] p=0.01).

Discussion

This is the first report on short and medium-term results in different anaesthetic management for patients undergoing TAVI with the CoreValve System and in the largest cohort of patients described so far. Despite the increasing number of patients undergoing TAVI, there is no general consensus regarding the role of the anaesthesiologists and their intraoperative management. Since the beginning of TAVI experience, recommendations have underlined the importance of the anaesthetist’s skills in the setting of this procedure10,11,17,18. Originally, GA was used worldwide because many aspects of the procedure were unknown, complications were less easily managed and because the operator considered transoesophageal echocardiography monitoring fundamental during the procedure2,9,10,18.

According to the latest results from the pilot European Registry of TAVI, the percentage of patients treated using GA was 63% with a wide variation among participating countries (0.3%-100%)19.

Furthermore, results from the National French TAVI Registry demonstrated a decline in the use of GA from 73.4% in 2010 to 65.0% in 2011, related to operators’ increasing experience6. In our study, the mean percentage of GA use during TAVI was even lower (355/1,316; 26.9%), mainly including patients who underwent access other than the transfemoral approach (149/242; 61.5%). Instead, general anaesthesia was the preferred regimen at the beginning of the operator’s learning curve. With increasing team experience and technology improvements, the use of LA increased over the years (p<0.001), restricting the use of GA to some surgical cutdown or to severely obese, orthopnoeic and restless patients20.

Above all, GA is known to carry some disadvantages, such as the cardiac depressant effect of general anaesthetics that may trigger cardiovascular instability upon induction of GA and during the procedure. In particular, hypotension and bradycardia on induction, and consequently the need for vasoconstrictors, can be very dangerous in patients affected by severe aortic stenosis21. LA instead avoids haemodynamic uncontrolled changes, is better tolerated by patients with pulmonary insufficiency, and allows instantaneous monitoring of any neurologic change in the patient or pain and discomfort that can be an indication of some complication. However, the possibility of a switch to full GA must be considered at any moment of the procedure22. We acknowledge that LA may prevent the use of transoesophageal echocardiography during the entire procedure; however, we believe that after the learning curve echocardiographic guidance is not mandatory. Moreover, if necessary, transoesophageal echocardiography can be used during LA management23. However, age, comorbidities and large bore instrumentation, causing possible pain or haemodynamic instabilities in some passage of the procedure together with potential complications, justify the need and importance of an anaesthesiologist in the setting of TAVI.

PROCEDURAL RESULTS

Procedural results were good and quite similar in both managements, confirming that TAVI can be performed with LA without additional procedural risks. Interestingly, we found a significantly longer procedural time and fluoroscopy time in the GA group due to a higher use of GA during the learning curve. The identification of the incidence and cause of LA failure is another important issue. A previous report revealed the incidence of LA failure to be 17% in 100 patients who underwent LA. Our results, according to the latest data, showed a lower rate of conversion to GA (2.9%), demonstrating that LA is consistent with the efficiency of this therapy8,24. These failures were mainly explained by haemodynamic instability and procedural complications which occurred in the first period of the learning curve.

EARLY AND LONG-TERM OUTCOMES

Our results indicate that patients undergoing TAVI under GA or LA have similar early and midterm outcomes. In particular, in-hospital and 30-day adverse events were quite low in both groups. Of note, the incidence of major and life-threatening bleedings was more frequent in patients treated with GA and there was a higher occurrence of acute kidney injury stage 3. Bleeding complications are mainly accounted for by the use of GA during the learning phase of TAVI when there was less knowledge of the procedure and by a higher incidence of peripheral vascular disease among patients treated with GA.

Nevertheless, these results demonstrate that during LA patients can be kept under control and their conscious state does not predict higher risks of vascular complications caused by an uncontrollable situation. We presume that conscious patients can indicate any local pain or inconvenience related to some manoeuvre, advising the operator and the anaesthesiologist.

The higher rate of acute kidney injury stage 3 in the GA group confirms previous data from other authors and our group23,25. Despite similar creatinine levels at baseline and the same amount of contrast used during the procedure, GA patients showed a decrease in kidney function. The relationship between acute kidney injury and GA may be correlated by the effects of an intraoperative decrease of mean arterial pressure induced by anaesthetic drugs. Furthermore, in the GA group the diffuse atherosclerosis and the higher incidence of bleeding complications may also contribute to an increased risk of postoperative kidney failure.

In accordance with previous papers, we confirmed that the LA group had the advantage of an earlier mobilisation with shorter intensive care unit and in-hospital stay compared to the GA group8,11. Generally, early mobilisation in elderly patients undergoing vascular or cardiac surgery results in a decrease of postoperative mortality and a reduction of postoperative complications26.

ANAESTHETIC MANAGEMENT AND VASCULAR ACCESS

GA is mostly related to alternative access due to the use of a surgical cutdown and is essential in patients treated via mini invasive access, such as the transapical or transaortic access. According to the latest results from the pilot European Registry and French Registry of TAVI, the procedures were performed with the use of LA for 37.1% and 40.8% via the femoral approach, respectively6,19. Conversely, in our experience, the use of LA was more frequent even in patients treated with an alternative femoral access. In particular, 80.8%, 47.9% and 0.1% of patients treated with a percutaneous femoral access, trans-subclavian access and transaortic access, respectively, underwent LA. Concerning the trans-subclavian access it has been demonstrated that, after the learning curve, it is possible to perform TAVI in a high percentage of cases under LA13,20,22. Although these experiences have increased and validated this approach, a few centres still use GA for trans-subclavian cases, justifying this choice by reason of the extreme frailty of some patients.

PROPENSITY SCORE ANALYSIS RESULTS

Since the two anaesthetic managements were addressed to different approaches and the GA patients were found to be at higher risk due to a higher prevalence of peripheral artery disease, we carried out a further evaluation in order to confirm our results. A total number of 255 patients who underwent GA were matched to 255 patients treated with LA by means of a propensity score analysis to generate two comparable groups of patients undergoing TAVI. This sub-analysis demonstrated the same results previously observed in the overall population. As expected, in the GA group we observed longer procedural time, higher use of a surgical vascular access, and a higher incidence of acute kidney injury stage 3. Furthermore, although we compared two groups of patients with similar baseline characteristics, we confirmed a higher rate of major and life-threatening bleeding and major vascular access-site complications in the GA group. This could be related to a more frequent use of GA during the learning phase of TAVI (Figure 1) when there was less knowledge of the procedure and the incidence of vascular complications was higher27.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

This was a multicentre, prospective registry with independent monitoring and event adjudication; data were self-reported and validated a posteriori. Moreover, it is not a randomised comparison between the two managements, but rather our intent was to prove the safety and non-inferiority of LA as an increasingly appropriate anaesthetic management. We performed a propensity score matching analysis to validate the results of the analysis, without accounting for the date of procedure or the centre effect. The later years of the procedure (from 2009 to 2012) are very well balanced between the two groups, while in 2007 and 2008 the majority of patients were treated under GA. Since our results relate to seven high-volume experienced centres, GA should be the preferred technique at the beginning of an implantation programme and in low-volume centres.

Conclusion

In experienced centres which have gone beyond their initial learning curve with TAVI, the selective use of local anaesthetic in a selected patient population can be associated with good clinical outcome. The possibility of using LA is an important tool over the transapical and direct aortic access, considering the risk of GA in elderly patients who suffer from multiple comorbidities. Nevertheless, as severe procedural complications are possible, an anaesthesiologist should always be present and be part of the team.

| Impact on daily practice Despite the increasing number of patients undergoing TAVI, there is no general consensus regarding the modalities of anaesthesia and the role of the anaesthesiologists. Our study demonstrated that, in experienced centres, TAVI under LA is as effective and safe as TAVI under GA, with the advantage of shorter procedural time and early recovery. Nevertheless, as severe procedural complications are possible, an anaesthesiologist should always be present as part of the team. |

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Agnese Rossi for her indispensable role in data collection and analysis.

Funding

Medtronic Italy is the sponsor of the ClinicalService Project.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Rossi is an employee of Medtronic Italia, an affiliate of Medtronic Inc. A.S. Petronio, F. Bedogni, F. Ettori, and A. Latib are consultants for Medtronic Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.