Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) represent a significant part of the workload of cath labs worldwide. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the treatment of choice for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and it is well established that an early invasive evaluation of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTEMI) yields better prognosis for patients.

Beyond the well-supported indication of PCI in ACS there is room for personalised treatment. Evidence arising first from pathological and biological studies, and later from in vivo observations with high-resolution intracoronary imaging, has demonstrated a large variety of mechanisms leading to the development of ACS that might, potentially, justify different treatment strategies. Available recommendations for ACS treatment are still based on the electrocardiographic and angiographic findings and are not sensitive to the specific underlying physiopathology1. Thus, current revascularisation guidelines state that stenting should be preferred over balloon angioplasty in the setting of primary PCI as it reduces the risk of abrupt closure, reinfarction, and repeat revascularisation. However, guidelines do not mention the investigation of the cause with intracoronary imaging as part of the ACS assessment and as a guide for treatment.

ACS can have both atherosclerotic and non-atherosclerotic causes. Among ACS caused by coronary atherosclerosis, plaque rupture and subsequent thrombosis is the most frequent cause of acute luminal obstruction2. Plaques that rupture are generally characterised by the presence of a large necrotic core, covered by a thin fibrous cap and infiltrated by macrophages. The interventional treatment of ACS has been designed focusing on this entity and emphasising the need for covering the plaque rupture with a stent.

However, almost one third of ACS are caused by coronary erosion. This is the most frequent lesion in women <50 years old dying of myocardial infarction. Erosion generally occurs over fibrous plaques and is characterised by the denudation of the endothelium and the presence of neutrophils and white thrombus3.

The relevance of identifying the presence of erosion stems from evidence suggesting that ACS caused by erosion have better prognosis and can be managed with specific revascularisation strategies4,5. As patients with erosion have less thrombus and generally do not have plaque causing severe luminal obstruction, they can be treated with thrombus aspiration and medical antithrombotic treatment without the need for further stenting. The EROSION study reported a series of patients with ACS with optical coherence tomography (OCT)-defined erosion treated with anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy (AAS+ticagrelor) without stent implantation. This treatment strategy showed satisfactory results with 49/53 patients (92.5%) free from major adverse cardiovascular events at one-year follow-up. Three patients needed revascularisation because of exertional angina but there were no new ACS at follow-up6. These results need to be validated in a larger trial, but they emphasise the value of underlying physiopathology identification in ACS management.

ACS can also have non-atherosclerotic causes such as spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), embolic occlusion and spasm. Regarding SCAD intracoronary imaging, OCT in particular has contributed significantly to increasing the recognition of this pathology which was previously underdiagnosed (especially type 2 with predominant intramural haematoma and type 3 that mimics atherosclerosis). The knowledge we have gained from OCT has increased our ability to recognise SCAD on angiography and currently intracoronary imaging is only performed in cases with suspicion based on the epidemiologic and angiographic characteristics where angiography is insufficient for diagnosis (angiotype 3 or unclear angiotype 2), always bearing in mind the risk of manipulating a dissected vessel7,8. The recognition of SCAD as the cause of ACS is critical in order to establish the treatment strategy: this is recommended to be conservative (unless there is ongoing ischaemia) given the tendency of SCAD to heal completely over time.

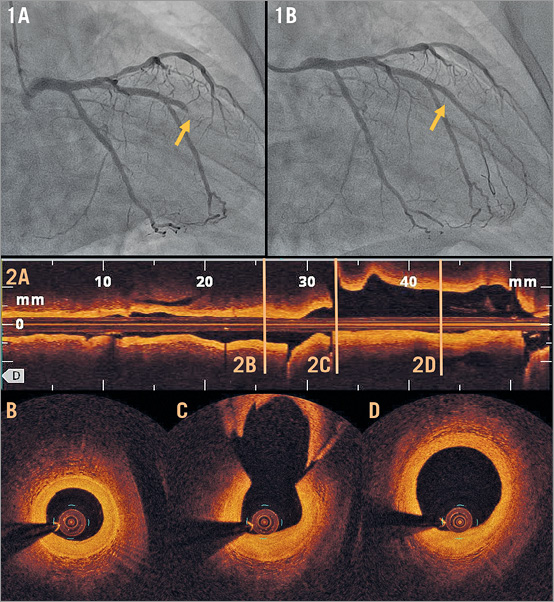

Another possible cause of ACS is embolic occlusions. They frequently affect distal vessels and are not amenable to interventional treatment; however, sometimes they can produce occlusion of the main epicardial arteries and be misdiagnosed as thrombotic occlusions caused by plaque rupture. Intracoronary imaging can be useful in these cases to clarify the substrate and guide treatment that might not always involve the use of a stent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Acute coronary syndrome caused by coronary embolism. A 70-year-old man with hypertension and type 2 diabetes was admitted for chest pain at rest. An ECG showed atrial fibrillation (not previously diagnosed) alternating with sinus rhythm with right bundle branch block. An angiogram was performed which showed an acute occlusion of an intermediate branch (panel 1A, yellow arrow) that was treated with thrombus aspiration with recovery of TIMI 3 flow (panel 1B, yellow arrow). After thrombus aspiration, no angiographic stenosis or filling defects suggestive of thrombus were visible. OCT was performed (panel 2A) to clarify the substrate showing a vessel with mild fibrous intimal thickening (panels 2B-2D) without signs of plaque rupture or thrombus and suggesting an embolic occlusion of the vessel as the cause of the ACS.

Identification of the underlying physiopathology in ACS therefore has therapeutic implications and should be performed using intracoronary imaging in cases in which the clinical and angiographic features suggest that the cause is not a plaque rupture: age <50 years old (especially in women), absence of coronary risk factors, lack of multi-segment or multivessel disease, non-severe angiographic stenosis9.

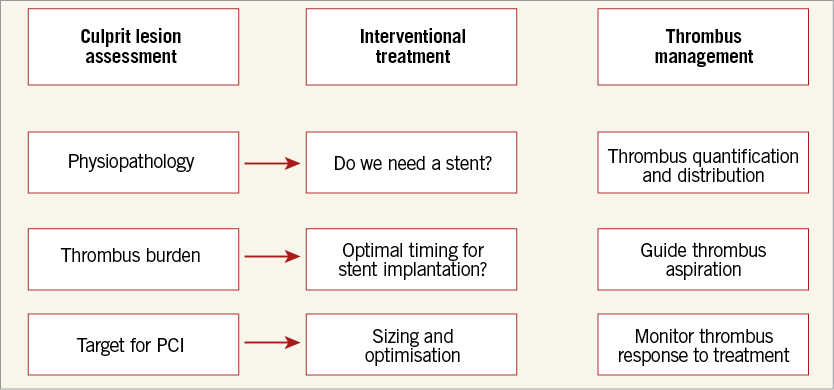

Apart from determining the cause of ACS and defining the need for interventional treatment, intracoronary imaging can also be very useful to guide the interventional procedure in these patients. In relation to thrombus management, OCT is much more sensitive than angiography to determine the thrombus burden and distribution and can be useful to guide thrombus aspiration and monitor thrombus response to treatment in cases that are going to be managed conservatively or in which stenting is delayed in order to avoid embolic complications10. Further, when there is need for stent implantation, intracoronary imaging provides useful information for sizing and optimisation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. OCT for the management of acute coronary syndromes.

In summary, ACS are heterogenous entities that can be caused by different substrates with different prognosis and therapeutic implications. The available intracoronary imaging techniques are capable of identifying the physiopathology in vivo, facilitating relevant decisions aimed at individualising treatment for our patients. Barriers to the application of this new strategy should be overcome by the possibility of providing our patients with the best care for their specific type of disease. It is time to go further in assessing the cause of ACS in our clinical practice.

Conflict of interest statement

N. Gonzalo has been a speaker at educational events for Abbott, Terumo and Boston Scientific.