Abstract

Hypertension is an extremely common condition and quantitatively the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Cardiovascular risk factors other than hypertension occur more frequently in hypertensive subjects and contribute to the elevated cardiovascular risk. Management of hypertensive subjects includes lifestyle modification and, usually, treatment with antihypertensive agents. Due to the limited blood pressure lowering effect of a single antihypertensive agent, more than 2/3 of hypertensive patients require at least two or more antihypertensive agents to achieve target blood pressure. For combination therapy combining an agent that interferes with the renin-angiotensin system with an agent that does not is recommended. Treatment adherence and persistence can be improved by using fixed-dose combinations instead of single agents.

Introduction

In the Western population hypertension is a very common condition with an estimated prevalence of 37%1. In the coming decades this prevalence is projected to increase related to ageing of the population and to the increasing number of subjects with obesity1. Due to its high prevalence hypertension is, worldwide, the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality2. When the total global impact of known risk factors on the overall burden of disease is calculated, 54% of strokes and 47% of ischaemic heart diseases are attributable to high blood pressure2. Equally important, as a consequence of cardiovascular morbidity, the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to hypertension are estimated to be 92 million, corresponding to 4.4% of the global total2.

Although high blood pressure (BP) in itself is a cardiovascular risk factor, it has been well established that, compared to their normotensive counterparts, hypertensive subjects have approximately twice as many co-existing risk factors such as dyslipidaemia, impaired glucose tolerance and abdominal obesity, further increasing cardiovascular risk.

For practical purposes, hypertension according to the WHO definition is defined when systolic BP is 140 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic BP is 90 mmHg or higher. This definition is highly arbitrary as observational studies have shown that the risk for cardiovascular disease already starts to increase with a systolic BP of 115 to 120 mmHg or higher and/or a diastolic BP of 75 mmHg or higher3. As a consequence, a BP of <120/80 mmHg in adults is considered to be normal.

Primary and secondary hypertension

Hypertension can be divided into primary and secondary hypertension. Approximately 80 to 90% of patients with hypertension have primary or essential hypertension. Primary hypertension is a complex trait due to the interplay of multiple genetic and environmental factors. Primary hypertension should not be considered as a single entity. For instance, a differentiation can be made between haemodynamic subtypes such as diastolic-systolic hypertension in young and middle-aged subjects and isolated systolic hypertension in older persons. Isolated systolic hypertension is closely related to the stiffening of large conductance arteries with increasing age. For all age categories obesity is strongly associated with BP and obesity-related hypertension, sometimes also called obesity-hypertension, differing from hypertension in lean subjects both with regard to haemodynamics and activation of neurohormones4. Apart from the influence of obesity itself, the frequently accompanying obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome can contribute to the development and maintenance of hypertension, probably through increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system5.

Subjects prone to developing hypertension already appear to have higher BP levels at a young age which, through a phase of pre-hypertension, develops into established hypertension around the age of 30-50 years. Established hypertension in turn can run an uncomplicated or a complicated course. In sporadic cases hypertension evolves into a so-called accelerated or malignant phase. The reason why this occurs in a minority of hypertensive subjects is unknown.

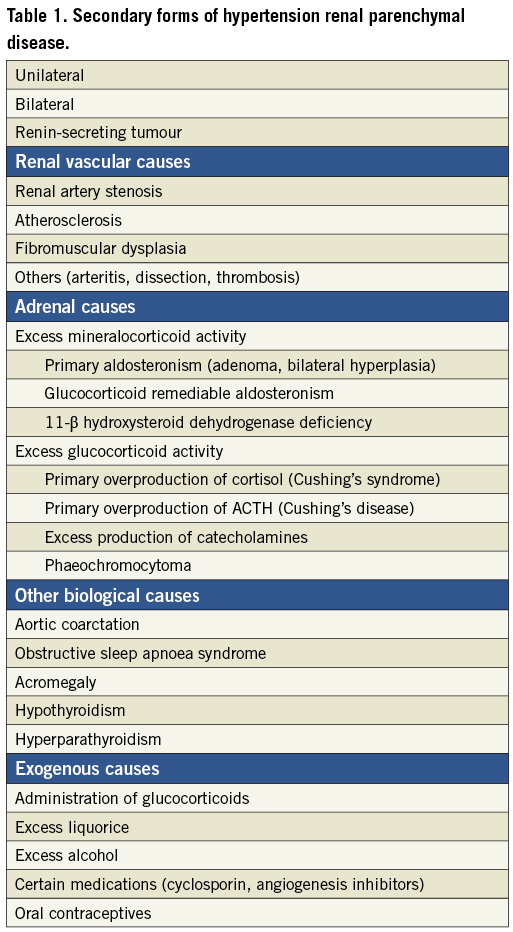

Numerous forms of secondary hypertension have been identified (Table 1). Differentiation of secondary hypertension from primary hypertension is clinically important, because secondary forms of hypertension have the potential to be cured, although, unfortunately, only in a restricted number of cases, and they sometimes require specific medical treatment such as, for instance, aldosterone receptor blockers in primary aldosteronism. Differentiation between primary and secondary hypertension is sometimes possible by means of medical history, physical examination and/or routine laboratory evaluation, but in many instances requires additional laboratory and/or radiological investigations. Renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis and primary aldosteronism are the most frequent causes of secondary hypertension. For a long time primary aldosteronism was considered to be a rare condition. Since the widespread application of the aldosterone-renin ratio as a screening test, primary aldosteronism has evolved as a rather frequent cause of secondary hypertension6. It is present in about 9% of patients with hypertension and its prevalence can increase to as high as 20% in patients with severe hypertension6. In a considerable number of patients primary aldosteronism is not associated with hypokalaemia and aldosterone and renin measurements are required to distinguish primary aldosteronism from primary hypertension.

Evaluation of the hypertensive patient

Evaluation of the hypertensive patient should answer the following questions:

1) Is hypertension primary or secondary?

2) Has it already resulted in hypertensive organ damage?

3) Apart from hypertension are there concomitant diseases present which may be important for the choice of antihypertensive treatment?

4) What is the overall risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the years ahead for that particular patient?

A carefully kept medical history provides information about the duration and the course of hypertension and the presence of cardiovascular or other symptoms or complications. Obtaining information about lifestyle issues, such as regular performance (or not) of physical exercise, amount of dietary salt intake, consumption of fruit and vegetables, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and use of agents that may affect blood pressure, is mandatory. Hypertension is usually a symptomless condition. Contrary to previous belief it may be associated with headache and a reduction of headaches has been reported after initiation of BP lowering treatment7. Early morning headache, as well as loud snoring, restless sleep and daytime somnolence, may be features of sleep apnoea. The family history is important with regard to the presence of hypertension and premature cardiovascular disease. Absence of hypertension in first-degree relatives may point to a secondary form of hypertension.

At physical examination accurate assessment of the blood pressure is essential. Numerous studies have shown that office blood pressure measurements in many instances are not representative of the true blood pressure, in part because of the white-coat effect8,9. Because of the poor performance of office BP measurements, home or 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements, in addition to or even instead of office measurements, are advocated in current hypertension guidelines. Body weight and height measurements are necessary for the calculation of body mass index and this parameter, when increased, together with the increased waist-hip ratio, is suggestive of the presence of the metabolic syndrome. Evaluation of the distribution of body fat, skin lesions and muscle strength is important for the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome or disease. Palpation of the thyroid gland in the neck and auscultation of the carotid arteries for the presence of bruits should be performed. Examination of the heart can provide information about size, rhythm disturbances and presence of valvular disease. Abdominal examination should focus on kidney size, which is typically enlarged in adult polycystic renal disease, and bruits over the aorta and renal arteries. Especially in younger patients with hypertension, diminished femoral as well pedal pulses are highly suggestive of aortic coarctation.

Fundoscopic examination allows direct inspection of small blood vessels. Fundoscopic examination has long been a routine part of the physical examination but, because of the low predictive value and lack of specificity of the milder degrees of retinal vascular changes to classify hypertension, fundoscopic examination is nowadays restricted to patients who are suspected of having hypertensive crisis in order to differentiate emergencies from urgencies, and also to patients with vision problems.

Routine laboratory evaluation should be restricted to measurement of serum concentrations of creatinine, sodium, potassium, lipids and glucose, and haemoglobin and haematocrit measurements, and a qualitative urine analysis as well as the assessment of microalbuminuria as a prognostic indicator of renal and vascular disease. An electrocardiogram is made to diagnose rhythm disturbances, cardiac ischaemia and the possible presence of left ventricular hypertrophy, although the sensitivity of an electrocardiogram for left ventricular hypertrophy is low. The ESH-ESC 2007 guidelines mentioned a number of additional tests that can be performed such as echocardiography, carotid ultrasound and ankle-brachial index and pulse wave velocity measurements10. These tests have their merits but, because of low added value and reasons of cost-effectiveness, they have no firm place in the routine evaluation of the hypertensive patient and are mainly reserved for research purposes. If, on the basis of the initial evaluation, a secondary cause of hypertension is suspected, additional investigations are almost always required. These additional investigations are expensive and should only be performed if further action is considered, such as angioplasty and stenting for an atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis, in the case of an abnormal result.

Treatment of high blood pressure

With regard to treatment of hypertension a distinction can be made between the population at large and individuals. In the past, most effort has been directed at the group with the highest levels of BP, and hypertension was almost always managed as an isolated risk factor, ignoring treatment of other risk factors. This high-risk strategy does little to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality of the general population if the low and intermediate-risk patients who make up the largest proportion of hypertensive patients at risk are ignored. Nowadays, many more people with mild-to-moderate hypertension are actively being treated with antihypertensive drugs, albeit a more effective strategy would be to lower the BP level of the total population. One such strategy would be the lowering of the sodium intake of the entire population. A reduction in dietary salt intake of 3 g per day on the basis of the current average consumption in the United States has been projected to reduce the annual number of new cases of coronary heart disease by 60,000 to 120,000, cases of stroke by 32,000 to 66,000 and cases of myocardial infarction by 54,000 to 99,000, and the number of all-cause deaths by 44,000 to 92,00011.

For all patients with hypertension, lifestyle modification, sometimes also called non-drug therapy, is recommended. Lifestyle modification is aimed not only at lowering BP but also at lowering other cardiovascular risk factors. Components of lifestyle modification include a healthy diet, reduction in sodium intake, regular physical exercise, low-risk alcohol consumption, attaining and maintaining an ideal body weight, and a smoke-free environment. Successful lifestyle modification may normalise BP in patients with mild hypertension. Unfortunately, for the majority of patients most of the mentioned lifestyle modifications are difficult to achieve and even more difficult to maintain, forcing the need to start with BP lowering agents in most patients. Furthermore, direct evidence is lacking that lifestyle modification prevents cardiovascular complications, but without doubt successful lifestyle modification almost always enhances the BP lowering potential of antihypertensive agents12.

Treatment with antihypertensives

Unequivocal evidence exists that treatment with antihypertensives reduces the increased burden of cardiovascular disease and mortality associated with hypertension13,14 . Evidence also exists that this benefit of antihypertensive treatment almost completely depends on the degree of BP lowering per se rather than on individual classes of BP lowering agents15. Intervention studies have shown that with antihypertensive treatment the reduction of cerebrovascular disease is almost twice as much as that of coronary artery disease, implying that high BP is a more important risk factor for cerebrovascular than for coronary artery disease. Optimal treatment requires that BP is lowered to <140/90 mmHg in all but the very old hypertensive patients and to <130/80 mmHg in patients with a high or very high cardiovascular risk due to the coexistence of diabetes mellitus and/or a history of coronary, cerebrovascular or renal disease.

The average BP lowering effect corrected for placebo of various antihypertensive agents in a standard dose amounts to 9.1 mmHg systolic and 5.5 mmHg diastolic with only a minimal difference between the individual agents of the different classes16,17. Doubling of the standard dose of a antihypertensive agent induces on average a 20% additional BP reduction, whereas a combination of two agents from different classes is associated with a doubling of the BP lowering effect, due to complementary antihypertensive mechanisms16,17. Because of the limited BP lowering effect, BP normalisation with monotherapy will be achieved in less than one third of the hypertensive population.

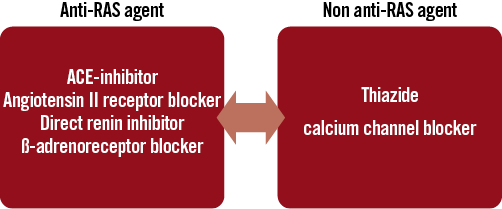

It is common practice to start with a single agent, the choice of which depends on demographic data and comorbidity. If the target BP is not reached, a second and if necessary a third agent is added, the so-called stepped-care approach. The ESH-ESC 2007 Hypertension Guidelines mention which BP lowering agents are first-choice agents and which combinations are preferred10. As outlined in Figure 1, antihypertensive agents can broadly be divided into agents that do or do not interfere with the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). Agents from both groups form logical combinations because of complementary antihypertensive mechanisms. Instead of a stepped-care approach, an alternative strategy is to start directly with two agents when the actual BP is 20/10 mmHg or more higher than the target BP. The advantage of such an approach is that the target BP will be reached faster, but sometimes, especially in the elderly, too fast with an increased chance of haemodynamically-related adverse effects.

Figure 1. Combination therapy in hypertension. Combination of an anti-RAS agent with a non anti-RAS agent is recommended. RAS: renin-angiotensin system

Treatment adherence and persistence to antihypertensives are notoriously poor in hypertension18,19. Apart from the misconceptions of the patient, in part related to insufficient education and instruction by healthcare providers, the frequency of dosing and the number of agents that have to be taken daily and their accompanying side effects may negatively influence adherence and persistence. For a number of BP lowering agents fixed-dose combinations are currently available, for instance an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB) with a thiazide. More recently, fixed-dose combinations with three components (ACEI of ARB + thiazide + calcium channel blocker) have become available. Studies have shown that treatment adherence improves by about 25% with the use of fixed-dose combinations compared to individual components20. In addition, the BP reduction with fixed-dose combinations is more pronounced without an increase in the number of side effects. Although fixed-dose combinations are usually more expensive than individual components, they may be cost-effective because of the beneficial effects on treatment adherence and persistence, and consequently on the greater proportion of hypertensive patients who achieve BP normalisation21.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.