Abstract

Aims: Medication non-adherence is a crucial behavioural risk factor in hypertension management. Forty-three to 65.5% of patients with presumed resistant hypertension are non-adherent. This narrative review focuses on the definition of adherence/non-adherence, measurement of medication adherence, and the management of medication non-adherence in resistant hypertension using multilevel intervention approaches to prevent or remediate non-adherence.

Methods and results: A review of adherence and resistant hypertension literature was conducted. Medication adherence consists of three different yet related dimensions: initiation, implementation, and discontinuation. To effectively measure medication non-adherence, a combination of direct and indirect methods is optimal. Interventions to tackle medication non-adherence must be integrated in multilevel approaches. Interventions at the patient level can combine educational/cognitive (e.g., patient education), behavioural/counselling (e.g., reducing complexity, cueing, tailoring to patient’s lifestyle) and psychological/affective (e.g., social support) approaches. Improving provider competencies (e.g., reducing regimen complexity), implementing new care models inspired by principles of chronic illness management, and interventions at the healthcare system level can be combined.

Conclusions: Improvement of patient outcomes in presumed resistant hypertension will only be possible if the behavioural dimensions of patient management are fully integrated at all levels.

Introduction

The prevalence of hypertension is estimated to be 30%-40% of the population, increasing with age1. Hypertension contributes significantly to the global burden of disease and is the leading disease burden risk factor in large parts of the world1,2. Hypertension is associated with 7.6 million deaths or 13.5% of global all-cause mortality2. Hypertension-related costs are high. In the UK, healthcare costs associated with hypertension amount to an estimated £10 billion per year3. State-of-the-art treatment of hypertension necessitates a combination of lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to increase control rates and reduce cerebral, cardiac and renal target organ damage and death1.

To be effective, blood pressure (BP) treatment must be accepted by the patient and adequately executed in the patient’s daily life1. Medication adherence, defined as “the process by which patients take their medication as prescribed4”, is thus a prerequisite to antihypertensive drug efficacy. Non-adherence, however, is highly prevalent (>50%) in patients taking long-term medications5, including antihypertensives, and is a major limiting factor to achieving and sustaining adequate BP control5-7.

A specific subgroup of hypertensive patients are those presenting with resistant hypertension. Resistant hypertension occurs when “a therapeutic strategy that includes appropriate lifestyle measures plus a diuretic and two other antihypertensive drugs belonging to different classes at adequate doses (but not necessarily including a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist) fails to lower systolic BP and diastolic BP values to below 140 mmHg and 90 mmHg, respectively1.” Resistant hypertension prevalence, depending on case finding and assessment methods used, ranges between 5% and 30% of all patients diagnosed with hypertension. The real prevalence, however, is estimated to be around 10%8,9, as many cases in the higher prevalence estimates are due to factors such as “white-coat” hypertension. Still, this prevalence results in 10-12 million persons suffering from resistant hypertension in Europe alone1. Clinical outcomes in resistant hypertension are poor because of the higher risk of cardiovascular complications and target organ damage1.

A significant proportion of patients who present with presumed resistant hypertension take their medications as prescribed. However, depending on the case finding methods, assessment methods for adherence and operational definitions used, between 43% and 65.5% of patients with presumed resistant hypertension were actually non-adherent to their antihypertensive treatment when medication adherence was explicitly evaluated3,10,11. More specifically, when medication adherence was assessed using blind urine assay in 375 patients presenting with uncontrolled hypertension, 53% of patients had been non-adherent10. In another study (n=84), antihypertensive adherence assessed by serum drug levels revealed that 65% of patients had drug levels lower than those expected if the medications were taken as prescribed11. Bunker et al3 invited 37 patients with presumed resistant hypertension to take their antihypertensive medication(s) under directly observed therapy (DOT). BP was subsequently followed up for up to 30 hours. Forty-three percent of patients achieved normal BP after DOT suggesting that medication non-adherence played a role in their uncontrolled hypertension3.

Medication non-adherence prevents the patient from benefiting from full exposure to pharmacological therapy. If clinical reasoning and decision-making for hypertension management are not informed by adherence information, increasingly escalating prescribing may follow. If the true reason for treatment goal failure is inadequately addressed medication non-adherence, the whole treatment approach might result in poor clinical outcomes, excessive costs of unused medications and the evaluation and treatment of subsequent clinical complications3,12. Furthermore, not explicitly including medication non-adherence in the interpretation of epidemiological data on resistant hypertension precludes understanding the true prevalence of resistant hypertension for the general population. Non-adherent patients and patients having true resistant hypertension are often commingled13.

This narrative review of medication non-adherence in clinical reasoning and decision-making in the management of patients presenting with presumed resistant hypertension builds upon the recent review on this topic by Burnier and colleagues13. This review focuses on the definition of adherence/non-adherence and medication adherence measurement, as well as the management of medication non-adherence in resistant hypertension using multilevel interventional approaches to prevent or remediate non-adherence5,14,15.

Defining and assessing medication adherence: disentangling dimensions of medication-taking behaviour

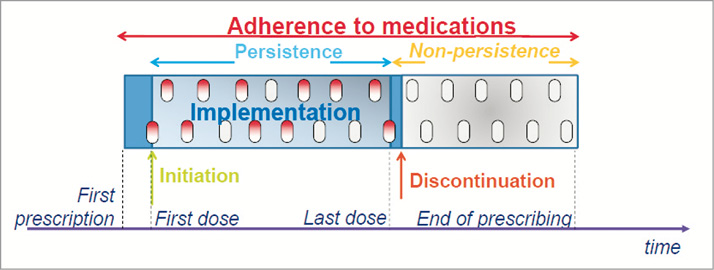

The European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme’s ABC project (Ascertaining Barriers for Compliance: policies for safe, effective and cost-effective use of medicines in Europe; http://abcproject.eu/index.php) taxonomy4 provides a solid framework for clinicians and researchers to define adherence and non-adherence. This taxonomy defines medication adherence as “the process by which patients take their medication as prescribed, further divided into three quantifiable phases: initiation, implementation and discontinuation” (Figure 1)4. Initiation occurs when a patient takes his/her first dose of medication. Implementation refers to “the extent to which a patient’s actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen, from initiation until the last dose is taken.” Discontinuation refers to that moment when therapy is stopped and no more doses are taken thereafter. Persistence is the duration between time of initiation and the time the last dose is taken4.

Figure 1. A new taxonomy for describing and defining medication adherence4.

Non-adherence to medications refers to those situations when problems with initiation or implementation (e.g., dose not taken, irregular dosing, or consecutive doses of medication not taken) as well as discontinuation of therapy (non-persistence) occur. Non-adherence to drug treatment in all three dimensions is substantial. Non-initiation rates in large-sample studies ranged from 4-9.8%16,17.

Many patients prematurely discontinue their prescribed medication. Using pharmacy refill data, one US study assessed persistence and found that, among 2.17 million patients in the first 30 days after a prescription was written, 31.5% of patients who had not taken medications before, and 7.6% of patients who had taken cardiovascular medication before, discontinued therapy by the end of one month18.

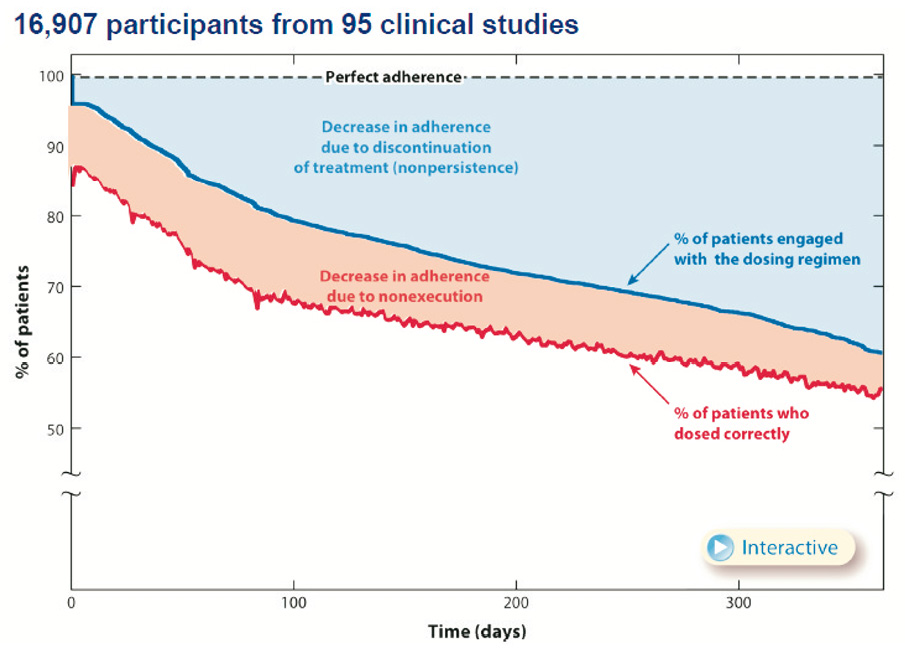

Non-adherence is primarily due to non-persistence, as shown by two large studies using electronic monitoring17,19, one focusing on hypertension19 and one focusing on a multitude of chronic illness regimens17 (Figure 2). Non-persistence was about 50% after one year17,19. Implementation (also called execution) issues cause about 10% of non-adherence over time, as can be inferred from the distance between the upper and lower line in Figure 2 17.

Figure 2. Non-adherence is primarily driven by non-persistence17.

Non-adherence to medication regimens can be intentional or unintentional20. Often, intentional non-adherence may be driven by inaccurate health beliefs such as the conviction that drugs are toxic, a fear of side effects or the belief that medications are not effective. Unintentional non-adherence refers to situations where non-adherence is not deliberate and is mostly related to forgetfulness and disruption of daily routines20.

Operational definitions of adherence behaviour are challenging to construct. Adherence literature typically uses a cut-off point of 80% of the prescribed doses as the point where they categorise patients as adherent or non-adherent, regardless of the measurement method used. This 80% cut-off point, however, has no scientific basis and its broad use overly simplifies a complex reality. A preferred approach is to identify a measure-specific, clinically meaningful definition of non-adherence. This definition would be determined empirically, based on the adherence level or, better still, the medication-taking patterns associated with poor outcomes. For example, Burnier and colleagues proposed a cut-off point of 90% using electronic monitoring as a clinically meaningful definition in resistant hypertension21.

Medication-taking patterns (e.g., correct dosing, skipping doses, drug holidays, dosing irregularly) are important in determining the clinical significance of antihypertensive non-adherence. Some drug classes have greater forgiveness than others. Drug forgiveness is defined as “the ability of a pharmaceutical agent to maintain therapeutic drug action in the face of occasional, variably long lapses in dosing22.” Differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics mean that while one drug might be very forgiving, skipping one or more doses of another drug might be associated with prompt loss of target blood levels and increased risk for poor clinical outcomes. While once-daily dosing has been shown to effectively improve adherence23,24, many once-daily drugs are less forgiving than equivalent twice-daily options25.

Assessment of adherence is crucial to inform clinical reasoning and decision-making in patients presenting with presumed resistant hypertension. Adequate diagnosis, treatment choice, treatment modifications and adherence interventions rely on accurate adherence assessment. Several direct and indirect assessment methods are available for assessing initiation, implementation and/or discontinuation26.

Direct methods refer to assays of medication, drug metabolites or tracers of patients’ bodily substances. Reliability of these methods is a function of the half-life of the drug or substance measured26. Drugs with a long half-life will provide information on adherence over a longer time period than those with a shorter half-life. Urine and blood assays have been used to assess adherence in patients with resistant hypertension10,11. Assays do not, however, give information on the patients’ dosing histories. Adherence can also be evaluated by direct observation3. Importantly, direct observation is restricted to clinical encounters.

Indirect measurement methods refer to patients’ written or oral self-report, collateral report by clinicians or caregivers, pill counts, prescription refills and electronic monitoring26. Using a non-threatening, non-accusatory and information-gathering approach is preferred when interviewing patients about adherence, something which requires excellent clinical communication skills. For instance, clinicians can ask: “We know that taking medications correctly every day, at the same time, can be difficult for many patients. Do you remember missing a dose of any of your medications in the past four weeks?” The BAASIS questionnaire, which integrates this approach27, has been used in large samples of hypertensive patients to assess medication adherence28,29. The BAASIS consists of six items assessing implementation and persistence dimensions of medication adherence. The BAASIS also includes a visual analogue scale to assess overall medication adherence. It has shown predictive validity in hypertensive patients29. Other self-report tools, such as the Morisky questionnaire30 and the Hill-Bone Compliance to High Blood Pressure Therapy Scale31, combine questions related to medication adherence and medication adherence risk factors, but neither fully assesses the different dimensions of the ABC taxonomy.

For settings with centrally managed pharmacy systems, prescription refill records can be used for indirect assessment of medication adherence. Medication adherence assessed this way is typically expressed in medication possession ratios32. Pharmacy refill records are a valuable, if inexact, method to capture initiation and discontinuation dimensions of adherence.

Admittedly the methods presented above have limitations, especially underreporting (i.e., self-reporting, collateral reporting, pill counts) and do not fully capture individual patients’ dosing histories (self-reporting, pill counting, collateral reports, prescription refills). Medication taking is dynamic, and different non-adherence patterns can occur within and among patients. For instance, patients can differ in implementation patterns (e.g., skipped/late doses, drug holidays), or discontinuation of the treatment regimen (persistence)4,17,33. Longitudinal assessment of the patient’s dosing history is indicated to reliably capture these different dynamics. Moreover, longitudinal dosing histories allow more reliable linking of medication-taking dynamics with clinical outcomes. The use of electronic monitoring has proved to be superior in this regard, including in hypertension7,19,21. Electronic monitoring refers to a pill bottle or medication box which electronically records each date and time that the medication container is opened and closed. Stored data can be downloaded to a computer, and adherence data are subsequently summarised in listings and graphics. Compared to other methods, electronic monitoring has superior sensitivity, although it remains an indirect method as ingestion is not proven26.

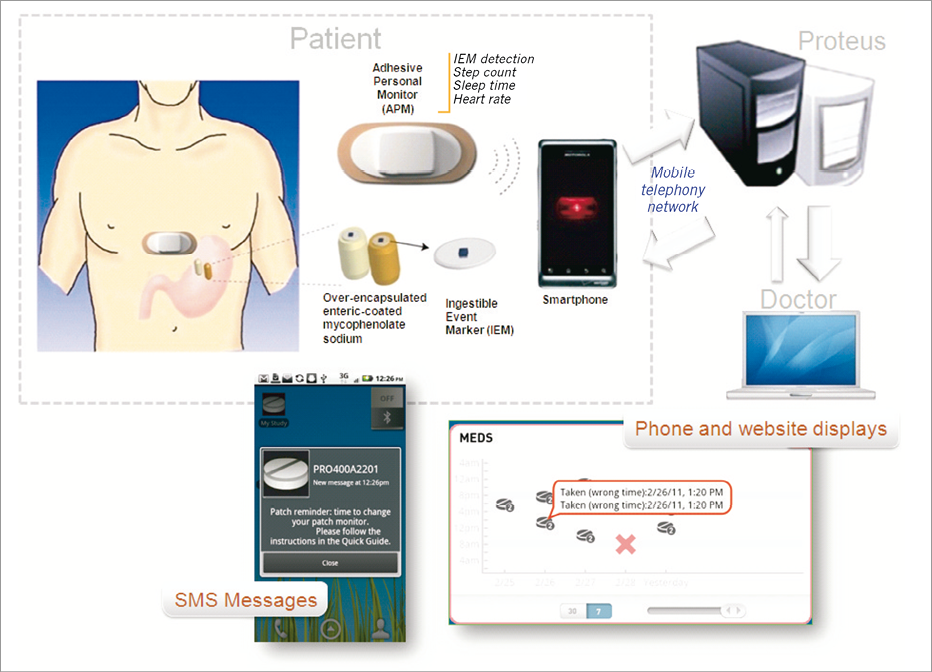

None of the above-mentioned direct or indirect methods can be seen as a gold standard for routine use in daily clinical practice. To increase the sensitivity of adherence measurement, a combination of different assessment methods is preferred26. Newer technologies combine the longitudinal assessment of patients’ dosing histories with direct evidence of medication ingestion, such as the Ingestible Sensor System (Proteus Biomedical Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA; Figure 3)34. These new methods show great promise for longitudinally monitoring medication adherence as well as other physiological parameters. While promising, these methods are still being tested and must overcome the obstacles of cost and patient acceptance.

Figure 3. Ingestible Sensor System (ISS) developed by Proteus Biomedical Inc. (Redwood City, CA, USA)34.

Managing medication non-adherence in resistant hypertension

Medication non-adherence is a crucial factor that should be addressed in the diagnosis and adequate treatment of presumed resistant hypertension. A multilevel, ecological approach35 that combines strategies at the levels of the patient, healthcare provider, healthcare organisation and healthcare system is preferred35. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that most tested adherence interventions have targeted the patient level alone24,36,37. There is also evidence on the efficacy of interventions targeting the healthcare provider, the healthcare organisation and healthcare system14,37,38,39. In addition, published guidelines summarise evidence for multilevel management of medication adherence in daily clinical practice5,40,41.

PATIENT LEVEL INTERVENTION

A combination of educational/cognitive, behavioural/counselling, and psychological/affective interventions has been shown to be the most effective at the patient level23. Educational/cognitive interventions “present information individually or in a group setting, delivering information about medication use and the importance of adherence verbally, in written form, and/or audio visually38.” Counselling/behavioural interventions “shape and/or reinforce behaviour, empowering patients to participate in their own care, while positively changing their skill levels or normal routines38.” Psychological/affective interventions “focus on patients’ feelings and emotions or social relationships and social support38.” E-health applications show promise as a cost-effective approach to support self-management interventions39.

Educational strategies are most often used in clinical practice, yet these strategies, which optimally should be succinct and targeted, while showing themselves to be primarily effective in increasing knowledge, are less effective in changing behaviour24.

Behavioural/counselling strategies include cueing (i.e., linking medication taking to routine behaviours), discussing with the patient how best to integrate the medication regimen into his/her daily routine and/or the use of medication aids such as pill boxes or other medication delivery systems38,42. A systematic review showed that electronic reminder systems (e.g., alarms) show short-term effectiveness in improving adherence37. A recent meta-analysis36 of studies assessing adherence by electronic monitoring showed that the most effective strategy was the combination of adherence monitoring using electronic monitoring and providing adherence feedback. Integrating feedback from home BP assessment is an effective option, and can be achieved by multiple methods. Using E-health technology allows for direct feedback loops and improved communication between patient and provider. Provider feedback may further reinforce patients’ adequate adherence or stimulate an intervention should an issue with non-adherence occur43. Another important effective behavioural intervention is the simplification of medication regimen complexity by reducing the number of medications, pills and dosing times per day44.

Psychological/affective interventions in a hypertensive population often include family members or friends as key supporters who provide social support, which contributes to long-term control of high BP. For example, they can remind the patient about appointments, provide transportation to appointments and manage refilling prescriptions. Such interventions have been effective at decreasing BP45.

In choosing interventions, it is crucial to assess the underlying dynamics of medication non-adherence and tailor the interventions to the triggering dynamics in an individual patient. Patient-level interventions should be adapted to a patient’s cultural background, and need to take into consideration specific factors such as age-related limitations and health literacy15,46,47.

HEALTHCARE PROVIDER LEVEL

Competencies for managing the behavioural component of medication treatment are neglected despite the call of the WHO for integrating these competencies in the healthcare providers’ curricula48. In one meta-analysis across 21 studies, training physicians in communication skills resulted in substantial and significant improvements in patient adherence49. Motivational interviewing has also been shown to be an effective strategy to enhance adherence and is recommended for behavioural management50.

Another intervention, aimed at improving patient centredness and clinicians’ communication skills with hypertension patients, significantly improved patient-reported participatory decision-making, facilitation and information exchange. Although BP was comparable between intervention and the usual care groups, a trend toward better BP control was observed in patients with uncontrolled hypertension51. Tele-health strategies also improve clinicians’ competencies in managing BP, including support for patient adherence. In a multicentre study in Brazil, an intervention targeting healthcare providers was effective at enhancing medication adherence, physical activity and sodium control, although self-reported medication adherence remained below 50%52.

HEALTHCARE ORGANISATION

Healthcare delivery models involving principles of chronic illness care53 have improved medication adherence in the treatment of hypertension management. For example, a meta-analysis demonstrated the superiority of hypertension management to decrease systolic BP by nurses using a treatment algorithm and by nurse-led telephone monitoring54. Hill et al demonstrated significant improvements in hypertension care and control using tailored educational, behavioural and pharmacologic interventions in young urban black men; a “special intervention group” was cared for by a dedicated nurse practitioner and community healthcare worker with a physician on call45.

HEALTH POLICY LEVEL

Adherence-enhancing interventions can also be implemented at the policy level. In the USA, a landmark trial tested the efficacy of providing full drug coverage for preventive medication to post-MI patients55. Outcomes included increased adherence in the intervention group, improvement in clinical outcomes and lower costs for patients while total spending remained comparable55.

Improvement in adherence management may also be fuelled by quality standards such as the Centre for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Five-Star Quality Rating System. In order for health plans to receive a 5-star rating, more than 75% of their patients must obtain at least 80% of medication prescribed from three drug classes, one of them being antihypertensive medications. This quality standard might fuel innovation in implementing adherence interventions at all levels to guarantee that this level is reached56.

Conclusion

Medication non-adherence is a crucial behavioural risk factor in clinical reasoning and decision-making for presumed resistant hypertension. A substantial proportion of patients with presumed resistant hypertension are non-adherent. Medication adherence consists of three different yet related dimensions: initiation, implementation and discontinuation. Assessing medication non-adherence requires a combination of direct and indirect measurement methods. Interventions to tackle the issue of medication non-adherence therefore call for a multilevel approach. Interventions at the patient level can combine educational/cognitive, behavioural/counselling and psychological/affective interventions. Improving competencies of providers, implementing new care models inspired by principles of chronic illness management, and interventions at the healthcare system level can be combined. Improvement of outcomes for patients with presumed resistant hypertension will only be possible if the behavioural dimension of patient management is fully integrated.

| Impact on daily practice Medication non-adherence is a crucial behavioral risk-factor that should be addressed in the diagnosis and treatment of presumed resistant hypertension. A crucial element in the evaluation of resistant hypertension is assessing patients’ medication adherence. Measuring adherence effectively requires a combination of direct (e.g. blood assay) and indirect methods (e.g. pill count). In order to tackle non-adherence and ultimately improve outcomes, a multi-level combined approach that integrates interventions at the patient level (i.e. reduction of complexity regimen, patient counselling), healthcare provider level (e.g. training in communication skills), healthcare organisation level (i.e. implementing principles of chronic illness management) and healthcare system factors (e.g. full drug coverage) is required. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.